Michael McConnell and Jack Baker

Michael McConnell (born 1942) and Jack Baker (born 1942)[1] are the first legally married same-sex couple in history. McConnell, a librarian, and Baker, a law student, were married in the U.S. state of Minnesota on 3 September 1971.

Both were activists in Minnesota from 1969 to 1980. They were invited often to appear publicly in the U.S. and Canada at college events, schools, businesses, churches, etc.[2]

Historians argued, correctly,[3] that the interpretation of "Marriages prohibited"[4] by the Minnesota Supreme Court in Baker v. Nelson (1971) did not apply to McConnell and Baker because they obtained a license and were married six weeks before that Court's opinion[5] became final.

FREE activists

Birth of America's first same-sex marriage

Weeks before the 1969 Stonewall riots,[6][7][8] two activists recruited local friends to join a team called "Fight Repression of Erotic Expression" as part of an outreach program sponsored by Minnesota Free University.[9]

Robert Halfhill, a graduate student who attended their lecture, left determined to form an independent group called "FREE"[10] on the Minneapolis campus (U of M) of the University of Minnesota. Attendees elected Jack Baker, a law student,[11] to serve as president.[12]

Interest in FREE expanded quickly. When a faculty committee qualified the group for all privileges enjoyed by student organizations,[13] it became "the first student gay organization to gain recognition in the upper mid-west."[14] Its "leaders [believed] it to be the first such organization on a Big Ten campus", the second such organization in the United States, following the Student Homophile League[15] recognized by Columbia University in 1967.[16]

Moving openly and aggressively, FREE slowly transformed Minneapolis into a "mecca for gays",[17] with members soon endorsing McConnell's demand for same-sex marriage.[18]

One member asked five major companies with local offices to explain their attitudes toward gay men and women. Three responded quickly,[19] insisting that they did not discriminate against homosexuals in their hiring policies. Only Honeywell objected.[20] Later, when faced with a denial of access to students, Honeywell "quietly [reversed] its hiring policy".[21]

Student Body President

In 1971, Baker campaigned[22] to become president of the Minnesota Student Association at the U of M. He urged students "to search out a new self-respect",[23] insisting that there was no need to wait for a new law to have a student serve with the regents. "The Regents already have the power to appoint students to all committees of the Board or Regents."

With a focus on self-pride, Baker was elected[24] then re-elected.[25] As student body president,[26] he continued to question why the Board of Regents ignored students when making its decisions.

Eventually, one non-voting student was invited to sit with the regents at each committee meeting. After graduation, the Governor signed into law a bill reserving one seat on the Board of Regents for an enrolled student.

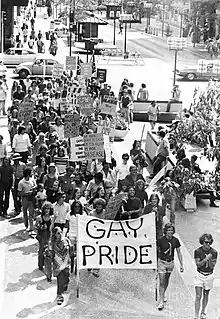

The birth of PRIDE

Also in 1971, members of FREE from Gay House invited friends to meet at picnics in Loring Park, near Downtown Minneapolis. Such self-pride events began in mid-June as a prelude to local 4th of July celebrations.[27] Jack Baker obtained permissions while Thom Higgins crafted Gay Pride[8] for both the banner and chant used to encourage allies, supporters and bystanders to defeat all attempts by the Catholic archbishop for Minneapolis and Saint Paul[28] to demean as a 'sin' either gay or pride.

"At the time, Jack was the Chair of the Target City Coalition, parent corporation for The Gay Pride Committee, which sponsored the annual Festival of Pride each June."[29] Such celebrations became the PRIDE tradition that thrives today in cities throughout the United States.

Egil Jonsson later shared his pride with friends. "I am in the [middle], 16 years old. This was the first gay rights march in the country that had a headline banner 'Gay Pride'. The following year all the marches adopted this and everyone called it Gay Pride. The banner was made by a friend, Thom Higgins, famous for throwing a cream pie into the face of Anita Bryant, anti-gay activist [in] 1978 on national television during a press conference. Thom and I dated, become [sic] friends in 1980."[30]

FREE continued working with U of M faculty to protect gay students from discrimination.[31] Central Administration approved the final draft of a new policy in 1972 and the Campus Committee on Placement Services began accepting complaints of unequal treatment by employers recruiting on campus. A member of FREE received class credit for a documentary about America’s first gay marriage,[32] which was aired by the local CBS affiliate on a Sunday in September 1973.[33]

Same-sex marriage activism

Lawsuit to obtain a marriage licence

In 1970, Minnesota's statutes did not forbid marriage between two adult men.[4] McConnell and Baker applied for a marriage license in Minneapolis, arguing that "what is not forbidden is permitted".[34]

The Clerk of District Court,[35] Gerald Nelson, denied their request. Refusal by lower courts to order Nelson to issue a license[36] was later affirmed by the Minnesota Supreme Court in Baker v. Nelson (1971).[37] However, before that decision became final, McConnell applied again, in a different county,[38] and received a marriage license.

The case received extensive media attention,[39] including appearances on the Phil Donahue Show;[40] Kennedy & Co. (WLS-TV, Chicago IL); and David Susskind Show[41] (New York, NY), where Baker insisted, "We're gonna win eventually, not this time but maybe the next time around."

The reaction from gay and civil liberty advocates was indifferent at best. Gay marriage was "rejected by early gay activists [in New York City] who were mostly interested in sexual freedom and gay liberation"[42] while leadership inside the American Civil Liberties Union showed "little or no enthusiasm".[43]

Allan Spear – professor of history at U of M – mocked McConnell and Baker as the "lunatic fringe".[44]

Same-sex marriage as a civil right

When invited to address members of the Ramsey County Bar Association,[45] Baker insisted that same-sex unions are "not only authorized by the U.S. Constitution" but are mandatory. "I am convinced that same-sex marriages will be legalized in the United States."

After Baker spoke to a forum of more than 2,000 at the University of Winnipeg,[46] Richard North began his "fight to be married" to Chris Vogel. The government of Canada legalized same-sex marriage in 2004.

NAACP's president, Benjamin Todd Jealous, insisted that as demands for same-sex marriage continued to grow worldwide, it became "the civil rights issue of our times".[8]

Speaking to the Associated Press, Baker explained that the "outcome was never in doubt because the conclusion was intuitively obvious to a first-year law student."[47]

Courts debate their marriage

McConnell’s marriage to Baker – like any marriage – depended on the interpretation of Minnesota’s marriage law.[4] Early results were not favorable,[48] with state and federal courts rejecting the marriage.

Denial of the original request in Minneapolis resulted in a direct appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court[49] by the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union.

A quick dismissal[50] was approved unanimously[51] after the clerk for Justice Harry Blackmun crafted a one-sentence rejection, "I just [didn't] think the court was ready at the time to take on the issue."[52]

Lower courts were forced to supervise a national debate before the high court decided that its decision to dismiss all demands for same-sex marriage must be overruled.[53]

Meanwhile, the Internal Revenue Service rejected their joint tax return for 1973.[54] McConnell responded by listing Baker as an adopted "child" on his tax returns from 1974 through 2004 for which he claimed a deduction as head of household. That benefit ended when Congress limited the deduction for an adopted child under the age of 19.[55]

Also, the Veterans Administration rejected a claim for benefits in 1976[56] because "Minnesota law prohibits same sex marriages . . ."

Adoption, name change, and a lasting marriage

In 1971, McConnell adopted[57] Baker whose legal name changed to Pat Lyn McConnell. Now with a gender-neutral name, McConnell applied and received a marriage license in Blue Earth County while the couple was visiting friends in Mankato.[38] Rev. Roger Lynn, a United Methodist minister, validated the marriage contract.[58][14]

Afterward, the Hennepin County Attorney convened a grand jury, which "studied the legality of the marriage but found the question not worth pursuing."[59]

The Family Law Reporter argued that the Minnesota high court's 1972 opinion[5] on the couple’s first attempt at marriage in Minneapolis – Baker v. Nelson – did not invalidate McConnell and Baker's Blue Earth County marriage license because the two were married "a full six weeks" before that decision was filed.[60]

Indeed, records at The National Archives[61] verify that "McConnell and Baker's marriage license [from Blue Earth County, MN] was never revoked. They are still married and have been for the last forty two years."

Legal professionals, academics and historians agree:

- Professor Thomas Kraemer insisted that FREE hosted "the first same-sex couple in history to be legally married".[62]

- Assistant Chief Judge Gregory Anderson ordered, "The marriage is declared to be in all respects valid."[3]

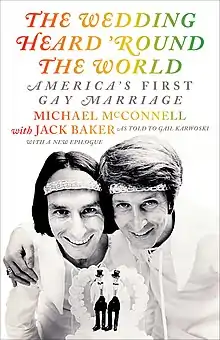

- Their wedding[58] was proclaimed to be America’s first gay marriage.[32]

- Historians vetted the marriage and affirmed it to be the "earliest same-gender marriage ever to be recorded in the public files of any civil government",[63] indeed anywhere.

Employment discrimination at U of M

In 1970, the University Librarian[64] invited Michael McConnell to head the Cataloging Division on the university's St. Paul campus. The Board of Regents refused to approve the offer after McConnell applied for a marriage license and regent Daniel Gainey insisted that "homosexuality is about the worst thing there is."

McConnell sued and prevailed in federal District Court.[65][66] The Board appealed to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals,[67][68] which concluded that the university did not restrict free speech. Instead, it insisted, McConnell wanted "to pursue an activist role in implementing his controversial ideas concerning the social status to be accorded homosexuals and thereby to foist tacit approval of the socially repugnant concept upon his employer."[69]

U of M students, more than 80%,[70] objected to the regents' action.

Hennepin County Library, then a diverse and growing system of 26 facilities, hired McConnell. The county Board of Commissioners applauded his 37 years of service when he retired as a Coordinating Librarian.[71]

In 2012, University of Minnesota president Eric Kaler offered McConnell an apology for the "reprehensible"[72] treatment he endured from the Board of Regents in 1970. McConnell accepted his assurance[73] that "such practices would not be consistent with the practices enforced today at the university."

Career in law and politics

In 1972, Baker led the DFL Gay Rights Caucus[74] at the State Convention of the Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party. The caucus persuaded delegates to support "legislation defining marriage as a civil contract between any two adults".[75] It is the first time a major United States political party endorses same-sex marriage.

After graduating from the University of Minnesota Law School,[76] Baker's request to take the bar examination raised questions of fraud surrounding his 1971 marriage license. The Minnesota Civil Liberties Union convinced[77] the State Board of Law Examiners that he was entitled to take the exam.[78]

Baker campaigned for Associate Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court,[79] each time arguing that his opponent ignored ethics[80] by heading the Minnesota News Council (MNC).[81] In the Plebiscite mailed to more than 14,900 attorneys in Minnesota, Baker challenged the bar to end special relationships between Justices of Minnesota's Supreme Court and MNC.[82] Nevertheless, collusion continued.[83]

Even after Minnesota's Supreme Court exited its offices at "230 State Capitol",[84] benefits were bestowed on judges who mediated private disputes.[85]

Vindication in later years

Though the 1972 case was dismissed[51] "for want of a substantial federal question", the couple obtained a legal marriage license before their attorneys filed an appeal and remained together as a married couple.[49]

In 2003, Baker and McConnell amended their individual tax returns for the year 2000, filing jointly as a couple, offering proof of a valid marriage license from Blue Earth County. The IRS challenged the validity of the marriage and argued that, even if the license were valid, the Defense of Marriage Act prohibits the IRS from recognizing it. When McConnell brought suit, the U.S. District Court for Minnesota upheld the IRS ruling[86] and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed,[87] saying that McConnell could not re-litigate the question decided in Baker v. Nelson.

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court decided "the issue Jack Baker and Mike McConnell tried to bring before it in 1972: Do same-sex couples have a constitutional right to get married?"[88] Minnesota's Attorney General argued, as a friend of the court: "The procreation rationale [used by the Minnesota Supreme Court] does not support the prohibition of same-sex marriage".[89] In their decision on Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Baker v. Nelson.

Interview

- Tom Crann (16 July 2015). "For Mpls. couple, gay marriage ruling is a victory 43 years in the making". Minnesota Public Radio News.

- T.J. Raphael (25 June 2015). "Meet the two men who managed to get the first known same-sex marriage license - back in 1970". The Takeaway, Public Radio International.

Short documentary

- Joseph Kase and Jeremiah Smith (Feb 2014). "Baker v. Nelson: The Original Case for Gay Marriage". YouTube.

- Pat Kessler (29 July 2013). "A Rare Glimpse At Minn.'s 1st Gay Wedding In 1971". WCCO-TV, Minneapolis.

Further reading

- Erik Eckholm (16 May 2015). "The Same-Sex Couple Who Got a Marriage License in 1971". The New York Times. www.nytimes.com.

- Lisa Grunwald (12 May 2015). "The 25 Most Influential Marriages of All Time". TIME.

- Pat Lyn McConnell (Jan 2014). "Who defined the gay agenda?" (PDF). Quatrefoil Library. p. 2.

- Claire Bowes (4 July 2013). "Jack Baker and Michael McConnell: Gay Americans who married in 1971". BBC News. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- Robert Frame (2012). "Minnesota Led the Two Coasts on Marriage Rights, and Should Do So Again: Jack Baker and Michael McConnell" (PDF). Quatrefoil Library. p. 5.

- Ken Bronson (2004). "A Quest for Full Equality" (PDF). University of Minnesota Libraries.

- Dennis Brumm (1971). "My Own Early Gay History". www.brumm.com.

- Shane Lueck (12 Nov 2015). "America's First Gay Marriage, 44 Years Later". Lavender Magazine.

- Memoir of Michael McConnell (2016) as told to Gail Langer Karwoski, "The Wedding Heard Heard 'Round the World: America's First Gay Marriage.", Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

References

- "Michael McConnell, Jack (Richard J.) Baker, and Lisa Vecoli".

- See: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volumes 2c and 2d], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- . . . "The September 3, 1971 marriage of James Michael McConnell and Pat Lyn McConnell, a/k/a Richard John Baker, has never been dissolved or annulled by judicial decree and no grounds currently exist on which to invalidate the marriage."

- McConnells against Blue Earth County, “CONCLUSIONS OF LAW”, Fifth Judicial District, File #07-CV-16-4559, 18 September 2018 at 4. Available online from U of M Libraries.

- 1970: "Minnesota Statutes Annotated", West Publishing Co.

- Chapter 517.01: Marriage a civil contract. "Marriage, so far as its validity in law is concerned, is a civil contract, to which the consent of the parties, capable in law of contracting, is essential."

- Chapter 517.03: Marriages prohibited. [The list does not include parties of the same gender.]

- Title of decision, as posted by the court.

- Salam, Maya (2019-06-04). "50 Years Later, What We Forgot About Stonewall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- York, Mailing Address: 26 Wall Street Federal Hall National Monument c/o Stonewall National Monument New; Us, NY 10005 Phone: 212-668-2577 Contact. "Stonewall National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- Though some credit New York as "the cradle of the modern LGBT rights movement", riots there had nothing to do with either "Gay Pride" celebrations or demands for "Gay Marriage", both of which began in Minneapolis from which they spread worldwide.

- Sources: McConnell Files, "America’s First Gay Marriage" [Binder #7, MEMORANDUM for the record], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- and: Michael K. Lavers, "NAACP president: Marriage is civil rights issue of our times" Washington Blade, 21 May 2012; available online

- Bulletin No. 5, New Courses [final entry]: K.A. Phelps, "The Homosexual Revolution", MINNESOTA FREE UNIVERSITY, 18 May 1969

- Address: "529 Cedar Avenue", near the U of M's expanding campus on the West Bank of the Mississippi, in the Cedar Riverside Neighborhood of Minneapolis.

- "Halfhill steered the group through the administrative channels needed to establish FREE as a student group".

- Bruce Johasen, "Out of Silence", Minnesota History (Spring 2019), 189

- A U of M student known by different names:

- March 1942: Richard John Baker, Certificate of Birth; name use for U of M enrollment

- September 1969: Jack Baker; name adopted to lead FREE activists and as the student body president [elected 1971 and re-elected 1972]

- August 1971: Pat Lyn McConnell, by Decree of Adoption; name used to apply for a marriage license

- Sources: McConnell Files, “Full Equality, a diary", volumes 6a-b (FREE: Gay Liberation of Minnesota), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- Neal R. Peirce, "The Great Plains States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Nine Great Plains States", George J. McLeod (1973), 145; available online, accessed February 7, 2014

- Wayne R. Dynes, "Homosexuality and Government, Politics and Prisons" (1992), 248; available online, accessed February 7, 2012

- News from, Fight Repression of Erotic Expression, 1 November 1969

- Merged later with the Columbia Queer Alliance.

- Schumach, Murray (May 3, 1967). "Columbia Charters Homosexual Group" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- Lily Hansen, GAY, "F.R.E.E. At Last", 11 May 1970, 13.

- See also: Ken Bronson, "A Quest for Full Equality", 2004; available online from U of M Libraries

- "Minnesota Hosts First Legally Sanctioned Same-Sex Marriage"

- For Release, Minnesota Student Association, 7 September 1971

- See also: for immediate release, FREE, 17 May 1970

- Anon., "Three big companies say they hire Gays", The Advocate, 30 September 1970

- "We would not employ a known homosexual"

- Letter to FREE from Gerry E. Morse, Vice President, Honeywell Inc., 29 June 1970

- Sources: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volumes 1a - d], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- Lars Bjornson, "A quiet win: Honeywell yields", The Advocate, 10 April 1974, 13

- "Mama D joined a collection of patriotic icons in this campaign poster for Jack Baker, the first openly gay student body president at the University of Minnesota."

- Caption: Jack Baker Comes Out - for Things That Count!

- Bill Huntzicker, "Dinkytown: Four Blocks of History", History Press (2016), page 161

- "He has spoken truth to power because he knows the power of truth."

- Endorsed by Minnesota Daily, "Baker for MSA president", 5 April 1971, page 4

- See also, platform for student body president: Jack Baker, "Policy Statement", March 1971

- "A total of 6,024 ballots cast topped the previous record of 5,049 in the 1958 election."

- Steve Brandt, "Baker wins in record vote," Minnesota Daily, 8 April 1971, 1

- See also: Gary Dawson, "Homosexual Credits U Election Victory to a New Sophistication", St. Paul Dispatch, 8 April 1971, 35

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volumes 6a - b], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- It was "the first time in the 121-year history of the U of M that a student body president has been re-elected."

- Vic Stoner, "Baker, Schwartz win MSA election", Minnesota Daily, 7 April 1972, 1

- See also: Associated Press, "Law senior elected U. student president", Austin Daily Herald, 7 April 1972, p. ?

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volumes 6a - b], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- He was known by different names:

- March 1942: Richard John Baker, Certificate of Birth

- September 1969: Jack Baker, name adopted to lead activists demanding gay equality

- August 1971: Pat Lyn McConnell, married name; by Decree of Adoption

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volumes 6a - b], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- also, Kay Tobin and Randy Wicker, "The Gay Crusaders", Paperback Library, New York (1972), 136

- "Twin Cities Gay and Lesbian Community Oral History Project: Interview with Koreen Phelps : Collections Online : mnhs.org". collections.mnhs.org. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- Example: Star Tribune, 1 June 2018, A1. "The wrenching bankruptcy that forced a reckoning on the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis for decades of clergy sexual abuse has culminated in a $210 million settlement for roughly 450 victims, the largest of its kind nationwide."

- Sources: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary", volume 8b (Vested interests opposing full equality), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries, Minneapolis

- Ken Bronson, "A Quest for Full Equality" (2004), p. 38. available online from U of M Libraries, Minneapolis

- Source: Facebook, 24 June 2019; also 29 February 2012

- Letter mailed to Jack Baker et al. from president Malcolm Moos, University of Minnesota, 11 February 1971; "I appreciate your willingness to serve on the Campus Committee on Placement Services."

- also: Gary Urban, "Complaint charges Honeywell discrimination", Minnesota Daily, 12 March 1973, 8

- Memoir of Michael McConnell, as told to Gail Langer Karwoski, "The Wedding Heard 'Round the World: America's First Gay Marriage," University of Minnesota Press (2016)

- Also: paperback release "with a new epilogue" (2020)

- Sponsored by Dave Moore, then a popular announcer on WCCO-TV

- Brandon Wolf posts on YouTube the FREE member's course work, including words to his parents

- Source: "Human Relations", University Media Resources

- Jack Baker, as told to Helen Barrett, "We had America's first gay marriage - in 1971", Financial Times Magazine, 7 August 2015; available online

- Minneapolis, 18 May [Fourth Judicial District includes Hennepin County]

- Appellant's Jurisdictional Statement, Baker v. Nelson, Minnesota Supreme Court docket no. 71-1027, at 3 - 4 (statement of the case)

- See also: Associated Press, "Marriage Is Out", Kansas City Star, 24 May 1970, 30A

- and: "Gay Marriage Plea Is Denied", St. Paul Pioneer Press, 19 November 1970, 27

- and: "Court Won't Let Men Wed", N.Y. Times, 10 Jan. 1971, 65

- "The institution of marriage as a union of man and woman, uniquely involving the procreation or rearing of children within a family, is as old as the book of Genesis".

- OPINION written by Justice C. Donald Peterson, Baker v. Nelson, 15 Oct 1971, 191 N.W.2d 185 at 186.

- Application, in Mankato, approved by the Clerk of District Court, Fifth Judicial District, which includes Blue Earth County

- "Daily Record", Mankato Free Press, 16 August 1971, p. ?

- Jack Star, "The Homosexual Couple," LOOK, 26 January 1971, 69 - 71

- See also: Michael Durham, "Homosexuals in revolt", LIFE, 31 December 1971, 68

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Gift #6, the marriage that made history", Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- Condon, Patrick (December 10, 2012). "Minn. gay couple in '71 marriage case still joined". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- Available online from Sasha Aslanian, "Gay rights pioneers Jack Baker and Michael McConnell predicted marriage victory in '70s", Minnesota Public Radio (16 May 2013)

- Professor Thomas Kraemer [Oregon State University], "Jack Baker deserves mainstream press coverage after gay marriage ruling", Tom's OSU, 7 July 2012; available online

- Letter from Norman Dorsen, General Counsel for ACLU, 1970

- published by Jason Smith, "Gay Pride Block Party Case", Friends of the Bill of Rights Foundation, January 2012, page 52; available online from U of M Libraries

- David von Drehle, "Gay Marriage Already Won", TIME, 8 April 2013, 22

- Bob Protzman, "Gay Marriage OK Predicted", St. Paul Pioneer Press, 22 October 1971, p ?

- Jack Baker, "The right to be human and gay", Manitoban, 13 March 1972; as reprinted by Ken Bronson in "A Quest for Full Equality", 2004, 69; available online from U of M Libraries;

- See: Mia Rabson, "Couple helped make history", Winnipeg Free Press, 17 September 2004, A4

- also: letter from Rich North to Jack [Baker] & Mike [McConnell], 20 September 2004; available online

- Patrick Condon, "Gay couple in 1971 marriage ruling reflect on new court challenges", Associated Press

- Reprinted in the St. Paul Pioneer Press, 11 December 2012, 3A+

- "What is believed to be the first same-sex marriage in the United States was performed in Minnesota."

- Pat Kessler, "A Rare Glimpse At Minn.'s 1st Gay Wedding In 1971", 31 July 2013; available online by WCCO [CBS, Minnesota].

- See also: Naomi Pescovitz, "Pastor Reflects Back on Minn. Gay Marriage", KSTP-TV [Minneapolis, MN], 16 May 2013; available online on YouTube

- and: Associated Press, "They're Mr. and Mr.", San Francisco Chronicle, 8 September 1971, 3

- Eckholm, Eric (May 16, 2015). "The Same-Sex Couple Who Got a Marriage License in 1971". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- 409 U.S. 810, 93 S.Ct. 37, 34 L.Ed.2d 65 (1972)

- Greenhouse, Linda (March 20, 2013). "Wedding Bells". New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Jess Bravin, "Supreme Court Clerk Remembers First Same-Sex Marriage Case", The Wall Street Journal, 1 May 2015; available online

- "The Court now holds that same-sex couples may exercise the fundamental right to marry."

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 26 June 2015 at 22-23. Available online.

- Anon., "Homosexual Couple Contest I.R.S. Ban On a Joint Return", The New York Times, 5 Jan. 1975, 55

- Anon., "Form 1040 Instructions", Internal Revenue Service (2005), 19; available online

- McConnell v. Nooner:

- District Court, No. 4-75-Civ. 566 (D. Minn. 20 April 1976)

- and: United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit: 547 F.2d 54 (8th Cir. 1976)

- But "regardless of popular conception, adoption is not limited to children" . . .

- MEMORANDUM by Judge Lindsay G. Arthur, Juvenile Division, in Minneapolis, 3 August 1971.

- Attached to: FINDINGS AND DECREE, File No. AD-19962, Fourth Judicial District, which includes Hennepin County.

- See also: Anon., "U student head adopted by homosexual friend", Minneapolis Tribune, 25 August 1971, 1A

- and: Associated Press, "Male's adoption by roommate OKd", Rocky Mountain News, Denver, 26 August 1971, 85

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "America’s First Gay Marriage" [Binder #3, file #2], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- "Pastor Roger Lynn holds up Baker and McConnell's marriage certificate" from the ceremony he conducted in Minneapolis [Hennepin County].

- Claire Bowes, "Jack Baker and Michael McConnell: Gay Americans who married in 1971", BBC News Magazine, 3 July 2013; available online.

- "Thus the marriage remained in effect."

- Anon., "Homosexual Wins Fight to Take Bar Examination in Minnesota", New York Times, 7 January 1973, 55.

- The "federal constitution prohibition against ex post facto laws . . . forbids the imposition of punishment for past conduct lawful at the time it was engaged".

- Bureau of National Affairs, "Gay married couple frustrated in adoption bid", The Family Law Reporter, 10 December 1974, page 2103

- Anon., "Hidden Treasures from the Stacks: pushing for equality", The National Archives at Kansas City, September 2013, 7; available online

- Professor Thomas Kraemer [Oregon State University], "Gay marriage discussion in 1953 vs. 1963 and today", Tom's OSU, posted 16 December 2013; available online

- Eskridge Jr., William N.; Riano, Christopher R. (2020). "Postscript". Marriage Equality: From Outlaws to In-Laws. Yale University Press. p. 752.

- Letter mailed to Michael McConnell; from Ralph H. Hopp, University Librarian, U of M, 27 April 1970

- and: letter delivered to Michael McConnell; from James F. Hogg, Secretary, Board of Regents, University of Minnesota, 10 July 1970; "... your conduct, as represented in the public and University news media, is not consistent with the best interest of the University."

- also: Randy Tigue, "Regent: FREE member case is a matter of public relations", Minnesota Daily, 16 July 1970, 1

- Sources: McConnell Files, “Full Equality, a diary", volumes 5a-e (The McConnell case), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- "McConnell v. Anderson, 316 F.Supp. 809 (D. Minn. 1970)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Bob Lundegaard, "University Ordered to Hire Homosexual", Minneapolis Tribune, 10 September 1970, 23

- "McConnell v. Anderson, 41F.2d193 (Oct 18, 1971)". OpenJurist. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- Anon., "Homosexual Wins a Suit over Hiring", New York Times, 20 September 1970; available online, accessed February 7, 2012

- Michelle Andrea Wolf and Alfred P. Kielwasser, eds., "Gay People, Sex, and the Media", Haworth Press (1991), 237; available online, accessed February 7, 2012

- "Do you think the University was justified in firing McConnell because of his open declaration of homosexuality?"

- yes = 10%, no = 81%, no opinion = 8%, other = 1%

- Source: Office of Student Affairs, "Research Bulletin", U of M, Winter 1972

- Agenda item 7A, "Commendation of Michael McConnell", Hennepin County Board of Commissioners, 30 November 2010; available online.

- "News", University News Service, 22 June 2012

- and: email from president Kaler to Logan Chelmo [class of 2018, Shakopee High School, Minnesota], 27 June 2018; action taken by our Board in 1970, "is today worthy of deep criticism - of rebuke and censure."

- also: letter from Robert Burgett, Senior Vice President, University of Minnesota Foundation, 17 February 2020; McConnell is enrolled as a member of the Heritage Society of the President's Club.

- Sources: McConnell Files, "America’s First Gay Marriage", binder #8 (Gift #1), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- Letter from Michael McConnell; addressed to university president Eric Kaler, 25 July 2012

- For Release Any Time, "Gay Machine Startles DFL Regulars", DFL Gay Rights Caucus, 9 June 1972.

- Resolution 71.d, "The 1972 DFL Platform", Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor State Central Committee, 9 - 11 June 1972 at Rochester, MN.

- "The Degree Of Juris Doctor With All Its Privileges And Obligations"

- Conferred by Malcolm Moos, President, University of Minnesota, 13 December 1972

- Anon., "Marriage hurdle cleared, Baker to take bar exams", Minneapolis Star, 28 December 1972, 2

- In a MEMO for the record, Baker explains why lobbying by the Chief Justice, Oscar Knutson, failed to deny him a license to practice law.

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 7a, section II], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- "Homosexual Wins Fights to Take Bar Examination in Minnesota" (PDF). New York Times. January 7, 1973. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- Douglas A. Hedrin, "Results of Elections of Justices to the Minnesota Supreme Court 1857-2016", Minnesota Legal History Project

- 1978: C. Donald Peterson

- 1980: George M. Scott

- 1982: John E. Simonett

- 1984: Douglas K. Amdahl

- 2002: Paul H. Anderson

- Details: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 8c], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- Code of Judicial Conduct

- 1970: Canon 5E. Arbitration. "A judge should not act as an arbitrator or mediator."

- 1994: Canon 4F. Service as Arbitrator or Mediator. "A judge shall not act as an arbitrator or mediator or otherwise perform judicial functions in a private capacity unless expressly authorized by law."

- "Effective August 1, 1989, all non-profit corporations are now required to file an annual registration once every calendar year. Please review the information on the label and read all directions before completing this form."

- Initial Annual Registration for a Minnesota Non-Profit Corporation, Office of the Secretary of State.

- Corporate Charter Number: L-559

- Corporate Name: Minnesota News Council

- [next: address cited is the chambers of Minnesota's Supreme Court before it moved to a new location]

- Registered Office Address: 230 State Capital, St. Paul, MN

- Signature: [Associate Justice] John E. Simonett

- Title of Office: Chair

- Date: 1/22/90

- Courtesy: Minnesota Historical Society

- Jack Baker, "2002 Judicial Plebiscite", Minnesota State Bar Association, September 2002

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 8c], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- Email from Susan Hansen, "Council Chairpersons", <[email protected]>, 14 June 2000.

- 1971-80: C. Donald Peterson

- [also: George M. Scott]

- 1980-82: Douglas K. Amdahl

- 1982-94: John E. Simonett

- 1995-97: Paul H. Anderson

- 1998-2006: Edward Stringer

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 7a], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- “Employees coped. They moved into the newly remodeled space floor-by-floor and coexisted with construction over a period of time from September through December [1994].”

- Roland C. Amundson, “A Search for Place: The History of the Minnesota Judicial Center”, Minnesota Court of Appeals, 1995, 67.

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 8c], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- Email from [Interim Director] Sarah E. Bauer, "Council Chair/President", Minnesota News Council, 11 May 2007.

- New address: 12 South Sixth Street, Suite 927, Minneapolis, MN 55402.

- Not until James H. Gilbert resigned as Associate Justice and was hired by MNC in 2007 as its "Hearing Chair" did MNC stop recruiting judges to mediate its disputes.

- Courtesy: McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" [volume 8c], Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries

- "McConnell v. United States, January 3, 2005" (PDF). US District Court for Minnesota. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- "McConnell v. United States, July 17, 2006" (PDF). 8th Circuit Court of Appeals. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Roger Parloff, "12 key moments that led to the Supreme Court's same-sex marriage case", fortune.com (posted 16 January 2015); available online

- Lori Swanson, Attorney General, State of Minnesota; "Brief of the State of Minnesota as AMICUS CURIAE in support of petitioners", Obergefell v. Hodges; In The Supreme Court of the United States, March 2015, 18; available online