Melikdoms of Karabakh

The Five Melikdoms of Karabakh, also known as Khamsa Melikdoms (Armenian: Խամսայի մելիքություններ, romanized: Khamsayi melikutyunner), were Armenian[1][2] feudal entities that existed on the territory modern Nagorno-Karabakh and neighboring lands from the times of the dissolution of the Principality of Khachen in the 15th century and up to the abolition of ethnic feudal formations in the Russian Empire in 1822.

Khamsa Melikdoms Խամսայի մելիքություններ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1603–1822 | |||||||||

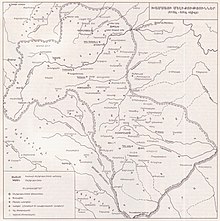

The five principalities of Karabakh (16th century) | |||||||||

| Status | Principality | ||||||||

| Capital | Shushi | ||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian | ||||||||

| Religion | Armenian Apostolic | ||||||||

| Government | Principality (Melikdom) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Iranian Armenia | ||||||||

• Established | 1603 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1822 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Artsakh |

|

| Antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Early Modern Age |

| Modern Age |

Etymology

Khamsa, also spelled Khamse or simply Khams means “Five Principalities” in Arabic. The principalities were ruled by meliks. The term melik (Armenian: Մելիք) meliq, from Arabic: ملك malik (king), designates an Armenian noble title in various Eastern Armenian lands. The principalities ruled by meliks became known in English academic literature as melikdoms or melikates.

History

Background

There were several Armenian melikates (dominions ruled by meliks) in various parts of historical Armenia: in Yerevan, Kars, Nakhichevan, Gegharkunik, Lori, Artsakh, Utik, Northwestern Iran and Syunik.[3]

The Five Melikdoms were ruled by dynasties that represented branches of the earlier House of Khachen and were the descendants of the medieval kings of Artsakh.

After the erosion of united Armenian statehood under the pressure from invading Seljuk Turks and Mongols, the Five Melikdoms were the most independent of all analogous Armenian principalities and saw themselves as holding onto the last bastion of Armenian independence.[4]

Autonomy

The realm of the meliks in Karabakh was almost always semi-independent and often fully independent. The meliks had their recruit armies headed by centurions, their own castles and fortresses. The military complexes that recruiting organizations, fortification systems, signal beacons, and logistical support were known as syghnakhs. There were two large syghnakhs shared by all meliks of Karabakh - the Major Syghnakh and the Lesser Syghnakh. The Major Syghnakh was located in melikdoms of Gyulistan (Vardut), Jraberd and Khachen and was supported by the fortresses of Gyulistan, Jraberd, Havkakhaghats, Ishkhanaberd, Kachaghakaberd and Levonaberd. The Lesser Syghnakh was located in the melikdoms of Varanda and Dizak, and was supported by the fortresses Shoushi, Togh and Goroz. Both Lesser and Major syghnakhs were parts of a legacy defense system that remained from the times of the Kingdom of Artsakh.[5]

The relationship between meliks and their subordinates was that of a military commanding officer and junior officer, and not of feudal lord and a serf. Peasants were often allowed to own land, were free and owned property.

These five Armenian principalities (melikdoms) in Karabakh[5] were as following:

- Principality of Gulistan - under the leadership of the Melik Beglarian family

- Principality of Jraberd - under the leadership of the Melik Israelian family, followed by the Alaverdians family in the 18th century and finally ruled by the princely house of Atabekian in the 19th century

- Principality of Khachen - under the leadership of the Hasan-Jalalian family (and at the end of 18th century partially ruled by melik Mirzahanyan)

- Principality of Varanda (until early 17th century part of principality of Dizak) - under the leadership of the Melik Shahnazarian family

- Principality of Dizak - under the leadership of the Melik Avanian family.

The Hasan-Jalalyan family that ruled the principality of Khachen was especially important, and was considered the most senior of the Five Melikdoms. They were direct descendants of Kings of Aghvank and symbolized the connection between patriarch Hayk, the eponymous progenitor of the Armenian People, considered as a great grandson of Noah, and medieval monarchs that ruled Armenia in the Middle Ages.

Hasan-Jalal traced his descent to the Armenian Arranshahik dynasty, a family that predated the establishment of the Parthian Arsacids in the region.[6][7] Hasan-Jalal's ancestry was "almost exclusively" Armenian according to historian Robert H. Hewsen, a professor at Rowan University and an expert on the history of the Caucasus:

Much of Hasan-Jalal Dawla's family roots were entrenched in an intricate array of royal marriages with new and old Armenian nakharar families. Hasan-Jalal's grandfather was Hasan I (also known as Hasan the Great), a prince who ruled over the northern half of Artsakh.[8] In 1182, he stepped down as ruler of the region and entered monastery life at Dadivank, and divided his land into two: the southern half (comprising much of Khachen) went to his oldest son Vahtang II (also known as Tangik) and the northern half went to the youngest, Gregory "the Black." Vahtang II married Khorishah Zakarian, who was herself the daughter of Sargis Zakarian, the originator of the Zakarid line of Armenian princes in Georgia. When he married the daughter of the Arranshahik king of Dizak-Balk, Mamkan, Hasan-Jalal also inherited his father-in-law's lands.[9]

In medieval times, the Hasan-Jalalian family branched into two functionally separate but connected lines: landed princes who ruled the Melikdom of Khachen and clergymen who manned the throne of Catholicos of Aghvank at the Holy See of Gandzasar of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The clerical branch of the family was especially important. In 1441, a top military commander from the Hasan-Jalalyan family in the service of the Kara Koyunlu orchestrated the return of the Holy See of the Armenian Apostolic Church from the Mediterranean town of Sis in Cilicia to its traditional location at Etchmadzin in Armenia.[10] Shortly after the event, Grigor X Jalalbegiants (1443–1465), representing the clerical branch of the Hasan-Jalalyans, was enthroned as the Catholicos of All Armenians at Etchmadzin.[11]

The principalities of Nagorno-Karabakh considered themselves direct descendants of the Kingdom of Armenia, and were recognized as such by foreign powers.[12]

The autonomous status of Armenian meliks in Karabakh was confirmed and re-confirmed by successive rulers of Persia. In 1603 Shah Abbas I recognized their special semi-independent status by a special edict.

Rivalries among the meliks prevented them from becoming a formidable and a unified power against the Muslims but unstable conditions in Persia eventually forced them to forget their squabbles and seek support from Europe and Russia. In 1678 Catholicos Hakob Jughayetsi (Jacob of Jugha, 1655–1680) called for a secret meeting in Echmiadzin and invited several leading meliks and clergymen. He proposed to head a delegation to Europe. The Catholicos died shortly after and the plan was abandoned. One of the delegates, a young man named Israel Ori, the son of Melik Haikazyan of Zankezur continued on and proceeded to Venice and from there to France. Israel Ori died in 1711 without seeing the liberation of the Armenian lands. In the second half of the 18th century melik Shahnazar of Varanda allied himself with Panah Khan Javanshir, the chieftain of a Turkic tribe, against other Armenian meliks which led to the downfall of the autonomous Armenian melikdoms of Karabakh.

The Armenian meliks maintained full control over the region until the mid-18th century. In the early 18th century, Persia's Nader Shah took Karabakh out of control of the Ganja khans in punishment for their support of the Safavids, and placed it under his own control[13][14] At the same time, the Armenian meliks were granted supreme command over neighboring Armenian principalities and Muslim khans in the Caucasus, in return for the meliks' victories over the invading Ottoman Turks in the 1720s.[15]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Nagorno-Karabakh became an epicenter of the idea of re-creating an independent Armenian state.[16][17] This state, centered on semi-independent Armenian principalities of Artsakh and Syunik, would be allied with Georgia and protected by Russia and European powers.[16] Armenian melik Israel Ori, who served in the armies of Louis XIV of France, was trying to convince Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine (1658–1716), Pope Innocent XII and Emperor of Austria to liberate Armenia from foreign yoke and sent large amounts of money to the armed forces of Karabakh Armenians.[18] Another prominent figure from Nagorno-Karabakh who worked to establish an independent Armenian entity in his homeland was Movses Baghramian.[19] Baghramian accompanied the Armenian patriot Joseph Emin (1726–1809), and tried to secure the help of Karabakh's Armenian meliks.[20]

Karabakh Khanate

Panah-Ali Khan Javanshir of Karabakh consolidated his local power by establishing a de facto independent khanate (land ruled by a khan), and subordinating the Five Melikdoms, with support of the Armenian prince Melik Shahnazar II Shahnazarian of Varanda, who first accepted Panah-Ali Khan's suzerainty.

Dissolution and Integration into the Russian Empire

The region came under Russian control in 1806 during the Russo-Persian War of 1804 to 1813, and was formally annexed in 1813 following the signing of the Treaty of Gulistan. The Russian Empire recognized the sovereign status of the five Armenian princes in their domains by a charter of the Emperor Paul I dated 2 June 1799.[21]

In 1822, the Russian Empire abolished ethnic feudal formations, and the territory previously ruled by the Five Melikdoms subsequently became part of the newly formed Elisabethpol Governorate, as part of the Yelizavetpolsky, Dzhevanshirsky, Dzhebrailsky, and Shushinsky uzeyds. Meliks preserved their rights and privileges after the rest of Eastern Armenia became part of the Russian Empire. Many of them became high-ranking military officers in the Russian imperial army.

Legacy

The name "Mountainous Karabakh" (Russian: Наго́рный Караба́х, romanized: Nagorny Karabakh) came to become the most prominent name for the region controlled by the Five Armenian Melikdoms ("Mountainous" as opposed to the lowland steppes of the Karabakh region). It maintained a strong Armenian presence and identity up into the modern age. It became the scene of several ethnic conflicts with neighboring Azerbaijanis, including the establishment of the Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within Azerbaijan SSR under the Soviet Union in the early 20th century, and the Karabakh movement in the late 20th century which led to the First Nagorno-Karabakh War amid the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the establishment of the Armenian Republic of Artsakh.

In literature and Art

The meliks of Karabakh inspired the historical novels The Five Melikdoms (1882) and David Bek (1882) by Raffi, the opera David Bek (1950) by Armen Tigranian and the novel Mkhitar Sparapet (1961) by Sero Khanzadyan. In 1944, David Bek the movie was filmed and in 1978, Armenfilm in association with Mosfilm produced another movie about the efforts of David Bek and Mkhitar Sparapet called Star of Hope.

References

- Britannica:"In mountainous Karabakh a group of five Armenian maliks (princes) succeeded in conserving their autonomy and maintained a short period of independence (1722-30) during the struggle between Persia and Turkey at the beginning of the 18th century; despite the heroic resistance of the Armenian leader David Beg, the Turks occupied the region but were driven out by the Persians under the general Nādr Qolī Beg (from 1736-47, Nādir Shah) in 1735."

- Encyclopaedia of Islam. — Leiden: BRILL, 1986. — vol. 1. — p. 639-640:"The wars between the Ottomans and the Safawids were still to be fought on Armenian soil, and part of the Armenians of Adharbaydjan were later deported as a military security measure to Isfahan and elsewhere. Semi-autonomous seigniories survived, with varying fortunes, in the mountains of Karabagh, to the north of Adharbaydjan, but came to an end in the 18th century."

- Hewsen, Robert. "The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study." Revue des Études Arméniennes. NS: IX, 1972, pp. 297-308.

- Hewsen, Robert H. "The Kingdom of Arc'ax" in Medieval Armenian Culture (University of Pennsylvania Armenian Texts and Studies). Thomas J. Samuelian and Michael E. Stone (eds.) Chico, California: Scholars Press, 1984, pp. 52-53. ISBN 0-8913-0642-0

- Րաֆֆի (Հակոբ Մելիք-Հակոբյան). Խամսայի մելիքութիւնները: Ղարաբաղի աստղագէտը: Գաղտնիքն Ղարաբաղի, Վիեննա, 1906. [Raffi (Hakob Melik-Hakobyan). The History of Karabagh's Meliks, Vienna, 1906, in Armenian. Another edition is «Խամսայի մելիքությունները», Երկերի ժողովածու, Երևան, 1964. Collection of Yerkrapah, Yerevan, 1964.]

- Ulubabyan, Bagrat (1975). Խաչենի իշխանությունը, X-XVI դարերում (The Principality of Khachen, From the 10th to 16th centuries) (in Armenian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences. pp. 56–59.

- Hewsen, Robert (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-2263-3228-4.

- Hewsen. "The Kingdom of Arc'ax", p. 47.

- Hewsen. "The Kingdom of Arc'ax", p. 49.

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, page 397

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, page 398

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 330, See: "Letter of Meliks of Karabagh to Prince Petemkin, January 23, 1790"

- (in Russian) Abbas-gulu Aga Bakikhanov. Golestan-i Iram; according to an 18th-century local Turkic-Muslim writer Mirza Adigezal bey, Nadir shah placed Karabakh under his own control, while a 19th-century local Turkic Muslim writer Abbas-gulu Aga Bakikhanov states that the shah placed Karabakh under the control of the governor of Tabriz.

- (in Russian) Mirza Adigezal bey. Karabakh-name, p. 48

- Walker, Christopher J. Armenia: Survival of a Nation. London: Routledge, 1990 p. 40 ISBN 0-415-04684-X

- Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 72

- George A. Bournoutian. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers, 1994. p. 17. ISBN 1-56859-011-3, 978-1-568-59011-0

- Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 73

- Life and Adventures of Emin Joseph Emin 1726-1809 Written by himself. Second edition with Portrait, Correspondence, Reproductions of original Letters and Map*. Calcutta 1918.

- A.R. Ioannisian. Joseph Emin. Yerevan, 1989, link to full text

- Robert H. Hewsen. Russian–Armenian relations, 1700–1828. Society of Armenian Studies, N4, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1984, p 37.