McDonnell XF-85 Goblin

The McDonnell XF-85 Goblin is an American prototype fighter aircraft conceived during World War II by McDonnell Aircraft. It was intended to deploy from the bomb bay of the giant Convair B-36 bomber as a parasite fighter. The XF-85's intended role was to defend bombers from hostile interceptor aircraft, a need demonstrated during World War II. McDonnell built two prototypes before the Air Force (USAAF) terminated the program.

| XF-85 Goblin | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| XF-85 serial number 46-523 in the National Museum of the United States Air Force | |

| Role | Parasite fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Aircraft |

| First flight | 23 August 1948 |

| Status | Canceled, 1949 |

| Number built | 2 |

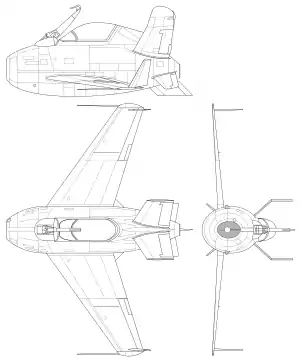

The XF-85 was a response to a USAAF requirement for a fighter to be carried within the Northrop XB-35 and B-36, then under development. This was to address the limited range of existing interceptor aircraft compared to the greater range of new bomber designs. The XF-85 was a diminutive jet aircraft featuring a distinctive egg-shaped fuselage and a forked-tail stabilizer design. The prototypes were built and underwent testing and evaluation in 1948. Flight tests showed promise in the design, but the aircraft's performance was inferior to the jet fighters it would have faced in combat, and there were difficulties in docking. The XF-85 was swiftly canceled, and the prototypes were thereafter relegated to museum exhibits. The 1947 successor to the USAAF, the United States Air Force (USAF), continued to examine the concept of parasite aircraft under Project MX-106 "Tip Tow", Project FICON, and Project "Tom-Tom" following the cancellation.

Design and development

During World War II, American bombers such as the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and Boeing B-29 Superfortress were protected by long-range escort fighters such as the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and North American P-51 Mustang. These fighters could not match the range of the Northrop B-35 or Convair B-36, the next generation of bombers developed by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). The development cost for longer-ranged fighters was high, while aerial refueling was still considered risky and technologically difficult.[1] Pilot fatigue had also been a problem during long fighter escort missions in Europe and the Pacific, giving further impetus to innovative approaches.[2]

The USAAF considered a number of different options including the use of remotely piloted vehicles before choosing parasite fighters as the most viable B-36 defense.[3] The concept of a parasite fighter had its origins in 1918, when the Royal Air Force examined the viability of Sopwith Camel parasite fighters operating from their 23 class airships. In the 1930s, the U.S. Navy had a short-lived operational parasite fighter, the Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk, aboard the airships Akron and Macon.[4] Starting in 1931, aircraft designer Vladimir Vakhmistrov conducted experiments in the Soviet Union as part of the Zveno project during which up to five fighters of various types were carried by Polikarpov TB-2 and Tupolev TB-3 bombers. In August 1941, these combinations flew the only combat missions ever undertaken by parasite fighters – TB-3s carrying Polikarpov I-16SPB dive bombers attacked the Cernavodă bridge and Constantsa docks, in Romania. After that attack, the squadron, based in the Crimea, carried out a tactical attack on a bridge over the river Dnieper at Zaporozhye, which had been captured by advancing German troops.[5] Later in World War II, the Luftwaffe experimented with the Messerschmitt Me 328 as a parasite fighter, but problems with its pulsejet engines could not be overcome.[1] Other late-war rocket-powered parasite fighter projects such as the Arado E.381 and Sombold So 344 were unrealized "paper projects".[6]

On 3 December 1942, the USAAF sent out a Request for Proposals (RfP) for a diminutive piston-engined fighter.[7] By January 1944, the Air Technical Service Command refined the RfP and, in January 1945, the specifications were further revised in MX-472 to specify a jet-powered aircraft.[4] Although a number of aerospace companies studied the feasibility of such aircraft, McDonnell was the only company to submit a proposal to the original 1942 request and later revised requirements.[4] The company's Model 27 proposal was completely reworked to meet the new specifications.[7]

The initial concept for the Model 27 was for the fighter to be carried half-exposed under the B-29, B-35, or B-36. The USAAF rejected this proposal, citing increased drag, and hence reduced range for the composite bomber-fighter configuration.[4] On 19 March 1945, McDonnell's design team led by Herman D. Barkey,[8] submitted a revised proposal, the extensively redesigned Model 27D.[9] The smaller aircraft had an egg-shaped fuselage, three fork-shaped vertical stabilizers, horizontal stabilizers with a significant dihedral, and 37° swept-back folding wings to allow it to fit in the confines of a bomb bay.[10] The diminutive aircraft measured 14 ft 10 in (4.52 m) long; the folding wings spanned 21 ft (6.4 m). Only a limited fuel supply of 112 US gal (93 imp gal; 420 l) was deemed necessary for the specified 30-minute combat endurance.[10] A hook was installed along the aircraft's center of gravity; in flight, it retracted to lie flat in the upper part of the nose.[10] The aircraft had an empty weight just short of 4,000 pounds (1.8 t).[11] To save weight, the fighter had no landing gear.[9][N 1] During the testing program, a fixed steel skid under the fuselage and spring-steel "runners" at the underside of the wingtips were installed in case of an emergency landing.[4][13] Despite the cramped quarters, the pilot was provided with a cordite ejection seat, bail-out oxygen bottle, and high-speed ribbon parachute.[14] Four .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns in the nose made up the aircraft's armament.[15]

In service, the parasite fighter would be launched and retrieved by a trapeze. With the trapeze fully extended, the engine would be airstarted and the release from the mother ship was accomplished by the pilot pulling the nose back to disengage from the hook.[14] In recovery, the aircraft would approach the mother ship from underneath and link up with the trapeze using the retractable hook in the aircraft's nose.[14] The anticipated production shift would see a mixed B-36 fleet with both "fighter carriers" and bombers[16] employed on missions.[17] There were plans that, from the 24th B-36 onward, provisions would be made to accommodate one XF-85, with a maximum of four per bomber envisioned.[15][N 2] Up to 10 percent of the B-36s on order were to be converted to fighter carriers with three or four F-85s instead of a bomb load.[N 3]

On 9 October 1945, the USAAF signed a letter of intent covering the engineering development for two prototypes (US serial numbers 46-523/4), although the contract was not finalized until February 1947.[18] After the successful conclusion of two reviews of a wooden mock-up in 1946 and 1947 by USAAF engineering staff,[3] McDonnell constructed two prototypes in late 1947.[9] The Model 27D was re-designated XP-85, but by June 1948, it was changed to XF-85 and given the name "Goblin".[N 4] There were plans to acquire 30 production P-85s, but the USAAF took the cautious approach – if test results from the two prototypes were positive, production orders for more than 100 Goblins would be finalized later.[16][18]

Operational history

During wind tunnel testing at Moffett Field, California, the first prototype XF-85 was accidentally dropped from a crane at a height of 40 ft (12 m), causing substantial damage to the forward fuselage, air intake, and lower fuselage.[9][20] The second prototype had to be substituted for the remainder of the wind tunnel tests and the initial flight tests.[21]

As a production series B-36 was unavailable, all XF-85 flight tests were carried out using a converted EB-29B Superfortress mother ship that had a modified, "cutaway" bomb bay complete with trapeze, front airflow deflector, and an array of camera equipment and instrumentation.[9] Since the EB-29B, named Monstro, was smaller than the B-36, the XF-85 would be flight tested, half-exposed.[21] To load the XF-85 into the host plane, a special "loading pit" was dug into the tarmac at South Base, Muroc Field, where all the flight tests originated.[22][N 5] On 23 July 1948, the XF-85 flew the first of five captive flights, designed to test whether the EB-29B and its parasite fighter could fly "mated".[13] The XF-85 was carried in a stowed position, but was sometimes tethered and extended into the airstream with the engine off, for the pilot to gain some feel for the aircraft in flight.[23]

McDonnell test pilot Edwin Schoch was assigned to the project, riding in the XF-85 while it was stowed aboard the EB-29B, before attempting a "free" flight on 23 August 1948. After Schoch was released from the bomber at a height of 20,000 ft (6,000 m), he completed a 10-minute proving flight at speeds between 180 and 250 mph (290–400 km/h), testing controls and maneuverability.[24] When he attempted a hook-up, it became obvious the Goblin was extremely sensitive to the bomber's turbulence, as well as being affected by the air cushion created by the two aircraft operating in close proximity.[24] Constant but gentle adjustments of throttle and trim were necessary to overcome the cushioning effect.[22] After three attempts to hook onto the trapeze, Schoch miscalculated his approach and struck the trapeze so violently that the canopy was smashed and ripped free and his helmet and mask were torn off.[25] He saved the prototype by making a belly landing on the reinforced skid at the dry lake bed at Muroc.[N 6] All flight testing was suspended for seven weeks while the XF-85 was repaired and modified. Schoch used the down period to undertake a series of problem-free dummy dockings with a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star fighter.[22]

After boosting the trim power by 50 percent, adjusting the aerodynamics, and other modifications,[22] two further mated test flights were carried out before Schoch was able to make a successful release and hookup on 14 October 1948.[27] During the fifth free flight on 22 October 1948, Schoch again found it difficult to hook the Goblin to the bomber's trapeze, aborting four attempts before hitting the trapeze bar and breaking the hook on the XF-85's nose. Again, a forced landing was successfully carried out at Muroc.[23]

With the first prototype's repairs completed, it also joined the flight test program, completing captive flights. While in flight, the Goblin was stable, easy to fly, and recoverable from spins, although initial estimates of a 648 mph (1,043 km/h) top speed proved optimistic.[21] The first test flights revealed that turbulence during approach to the B-29 was significant, leading to the addition of upper and lower fins at the extreme rear fuselage, as well as two wingtip fins to compensate for the increased directional instability in docking.[9] All the initial flights had the hook secured in a fixed position, but when the hook was stowed and later raised, the resulting buffeting added to the difficulty in attempting a hookup. To address the problem, small aerodynamic fairings were added to the hook well that reduced the buffeting when the hook was extended and retracted.[22] When testing resumed, on the 18 March 1949 test flight, Schoch continued to have difficulty in hooking up, striking and damaging the trapeze's nose-stabilizing section, before resorting to another emergency belly landing.[23] After repairs to the trapeze, Schoch flew the first prototype on 8 April 1949, completing a 30-minute free flight test, but after three attempts, abandoned his efforts and resorted to another belly landing at Muroc.[28][N 7]

Aware of the problems revealed in flight tests, McDonnell reviewed the program and proposed a new development based on a more conventional design promising a Mach 0.9 capability, using alternatively a 35° swept wing and delta wing.[29] McDonnell also considered adding a telescoping extension to the docking trapeze that would extend the device below the turbulent air under the mother ship.[28] Before any further work on the trapeze, other modifications to the XF-85, or continued design studies on its follow-up could be carried out, the USAF[N 8] canceled the XF-85 program on 24 October 1949.[31]

Two main reasons contributed to the cancellation. The XF-85's deficiencies revealed in flight testing included a lackluster performance in relation to contemporary jet fighters, and the high demands on pilot skill experienced during docking revealed a critical shortcoming that was never fully corrected.[29] The development of practical aerial refueling for conventional fighters used as bomber escort was also a factor in the cancellation.[21][13] The two Goblins flew seven times, with a total flight time of 2 hours and 19 minutes with only three of the free flights ending in a successful hookup.[21] Schoch was the only pilot who ever flew the aircraft.[32]

Further developments

Despite cancellation of the XF-85, the USAF continued to examine the concept of parasite aircraft as defensive fighters through a series of projects. These included Project MX-106 "Tip Tow", Project FICON, and Project "Tom-Tom" – which involved fighter aircraft attached to bomber aircraft by their wingtips.[33] Project FICON ("fighter conveyor") emerged as an effective Convair GRB-36D and Republic RF-84K Thunderflash combined bomber-reconnaissance-fighter, although the role was changed to that of strategic reconnaissance.[16] Project FICON drew heavily on data from the abortive XF-85 project and closely followed McDonnell's recommendations in designing a more refined trapeze.[34] A total of 10 converted B-36s and 25 reconnaissance fighters saw limited service with the Strategic Air Command in 1955–1956, before they were supplemented by more effective aircraft and satellite systems.[35]

Aircraft on display

After the program's termination, the two XF-85 prototypes were stored, before being surplussed and relegated to museum display in 1950.[29]

- 46-0523 – National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. Following the cancellation of the program, the aircraft was transferred to the museum on 23 August 1950 and was one of the first experimental aircraft to be displayed at the new Air Force Museum. For several decades, the aircraft was displayed alongside the museum's Convair B-36. In 2000, the aircraft was moved to the museum's Experimental Aircraft Hangar. Museum staff and visitors objected to this move, believing the aircraft should be displayed alongside the B-36 to properly represent its original design intentions.[36]

- 46-0524 – Strategic Air and Space Museum in Ashland, Nebraska. It was originally transferred to the Norton Air Force Base (near San Bernardino, California) in 1950, still in a damaged state after its last emergency landing. When the base museum was closed and its collection dispersed, the second XF-85 prototype languished in an unrestored condition as part of the Tallmantz private collection in California, until being acquired by Offutt AFB. It is now refurbished and displayed on its ground-handling trestle, nestled under the wing of a B-36J bomber (serial number 52-2217).[37]

Specifications

Data from Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters,[38] McDonnell XF-85 Goblin : USAF Museum factsheet,[36] McDonnell XF-85 : Boeing.com factsheet[13]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 14 ft 10 in (4.52 m)

- Wingspan: 21 ft 1 in (6.43 m) wings spread

- Height: 8 ft 3 in (2.51 m)

- Wing area: 90 sq ft (8.4 m2)

- Empty weight: 3,740 lb (1,696 kg)

- Gross weight: 4,550 lb (2,064 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 5,600 lb (2,540 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Westinghouse XJ34-WE-22 turbojet engine, 3,000 lbf (13 kN) thrust

Performance

- Maximum speed: 650 mph (1,050 km/h, 560 kn) estimated[N 9]

- Endurance: 1 hour 20 minutes

- Service ceiling: 48,000 ft (15,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 12,500 ft/min (64 m/s)

- Wing loading: 51 lb/sq ft (250 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.66

Armament

- 4 x .50 cal in (12.7 mm) M3 Browning machine guns

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- A fixed tricycle landing gear was considered for the flight tests but was discarded as the drag was excessive.[12]

- The initial specification called for the B-36 carrier aircraft to be able to carry either one F-85 and one atomic bomb or three F-85s.[9]

- The modifications included a structurally reinforced bomb bay that included the trapeze apparatus and an "umbilical" fueling station. In operational use, provisions for repair of oxygen and other mechanical systems, as well as replenishing ammunition were contemplated.[16]

- This name does not follow McDonnell practice and is the name that the USAAF gave to the aircraft.[15] McDonnell personnel nicknamed the aircraft "Bumble Bee."[19]

- The XF-85 were hooked onto fully extended trapeze and then hoisted into the mother ship.[22]

- Rogers Dry Lake and Rosamond Dry Lake made up emergency landing areas at Muroc.[26]

- On the last XF-85 flight, after completing a lengthy flight test, due to the limited fuel on board, Schoch was forced to abandon further attempts to dock.[22]

- The USAF was formed as a separate branch of the military on 18 September 1947 under the United States National Security Act of 1947.[30]

- No speed trials were attempted and the highest speed reached during any of the flights was 362 mph (582 km/h).[22]

Citations

- O'Leary 1974, p. 37.

- Gunston 1975, p. 483.

- Sundey 1985, p. 10.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, p. 81.

- Lesnitchenko 1999, pp. 4–21.

- Lepage 2009, pp. 257, 258.

- Cowin 2011, p. 36.

- Pace 1991, p. 55.

- Gunston 1975, p. 485.

- Gunston 1975, p. 484.

- Winchester 2005, p. 151.

- Sundey 1985, p. 12.

- "McDonnell XF-85 Goblin Parasite Fighter". www.boeing.com. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- O'Leary 1974, p. 38.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, pp. 82–83.

- Gunston 1975, p. 487.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, pp. 80–81.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, p. 82.

- Pace 1991, p. 57.

- Cowin 2011, pp. 37–38.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, p. 85.

- O'Leary 1974, p. 40.

- Cowin 2011, p. 38.

- Smith 1967, p. 1061.

- Gunston 1981, pp. 127–128.

- "The Lake Beds: Edwards Air Force Base." NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. Retrieved: 2 October 2011.

- Gunston 1981, p. 128.

- Cowin 2011, p. 39.

- Smith 1967, p. 1062.

- "United States Air Force." United States Air Force, September 2009. Retrieved: 6 August 2011.

- Yeager and Janos 1986, p. 179.

- Dorr 1997, p. 101.

- Miller 1977, p. 163.

- Sundey 1985, p. 19.

- Davis and Menard 1983, p. 37.

- "McDonnell XF-85 Goblin". National Museum of the US Air Force™. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "XF-85 "Goblin" – Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum". sacmuseum.org. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Jenkins and Landis 2008, pp. 81–82.

Bibliography

- Allen, Francis (Winter 1993). "The Ultimate Escort?: McDonnel XF-85 Goblin". Air Enthusiast. No. 52. pp. 17–23. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Cowin, Hugh W. "McDonnell's unmanageable Goblin." Aviation News, June 2011.

- Davis, Larry and David Menard. F-84 Thunderjet in Action (Aircraft No. 61). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1983. ISBN 978-0-89747-147-3.

- Dorr, Robert F. "Beyond the frontiers: McDonnell XF-85 Goblin: The built-in fighter." Wings Of Fame, Volume 7, 1997.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare, Volume 5. London: Phoebus, 1978. ISBN 978-0-8393-6175-6.

- Gunston, Bill. "McDonnell XF-85 Goblin." Fighters of the Fifties. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 1981. ISBN 0-933424-32-9.

- Gunston, Bill. "Parasitic Protectors." Aeroplane Monthly, Volume 3, No. 10, October 1975.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis. Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. Aircraft of the Luftwaffe, 1935–1945: An Illustrated Guide. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7864-3937-9.

- Lesnitchenko, Vladimir. "Combat Composites: Soviet Use of 'Mother-Ships' to Carry Fighters, 1931–1941." Air Enthusiast, No. 84, November/December 1999.

- Miller, Jay. "Project Tom-Tom." Aerophile, Volume 1, No. 3, December 1977.

- O'Leary, Michael. "McDonnell's parasite." Air Combat, Volume 2, No. 2, Summer 1974.

- Pace, Steve. X-Fighters: USAF Experimental and Prototype Fighters, XP-59 to YF-23. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1991. ISBN 0-87938-540-5.

- Smith, Richard K. "An Escort Appended... The Story of the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin." Flying Review International, Volume 22, No. 16, December 1967.

- Sundey, Terry L. "Built-in Escort: The story of McDonnell's XF-85 'Goblin' parasite fighter." Airpower, Volume 15, No. 1, January 1985.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio: Air Force Association, 1975 edition.

- Winchester, Jim. "McDonnell XF-85 Goblin". Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press, 2005. ISBN 1-59223-480-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to XF-85 Goblin. |