Maulbronn Monastery

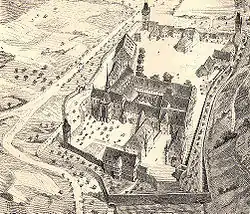

Maulbronn Monastery (German: Kloster Maulbronn) is a former Cistercian abbey and ecclesiastical state as an imperial abbey in the Holy Roman Empire located at Maulbronn, Baden-Württemberg. The monastery complex, one of the best-preserved in Europe, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.

| Maulbronn Monastery | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

German: Kloster Maulbronn | |||||||||||||

Maulbronn Abbey, circa 2017

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Website | |||||||||||||

| www | |||||||||||||

| Official name | Maulbronn Monastery Complex | ||||||||||||

| Criteria | Cultural (ii), (iv) | ||||||||||||

| Reference | 546rev | ||||||||||||

| Inscription | 1993 (17th session) | ||||||||||||

The monastery was founded in 1147 by a group of Cistercian monks who had been moved from an abandoned project 8 km (5.0 mi) away in present-day Mühlacker. Maulbronn experienced rapid economic and political growth in the 12th century, but then hardship in the late 13th century and the 14th century. Prosperity returned in the 15th century and lasted until Maulbronn was annexed by the Duchy of Württemberg in 1504. Over the 16th century, the Cistercian monastery was dissolved and replaced with a Protestant seminary. It also became the seat of an important administrative district of the Duchy and later Kingdom of Württemberg.

The complex, surrounded by turreted walls and a tower gate, today houses the Maulbronn town hall and other administrative offices, and a police station. The monastery itself contains an Evangelical seminary in the Württemberger tradition and a boarding school.

History

Imperial Monastery of Maulbronn Reichskloster Maulbronn | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Status | Imperial Abbey | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Abbey founded | 1147 | ||||||||

• Placed under Imperial protection | 1156 | ||||||||

• Annexed by Württemberg | 1504 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In 1138, a free knight named Walter von Lomersheim donated an estate at Eckenweiher (now Mühlacker)[1] to the Cistercian Order for the establishment of a new monastery.[2][3] The donation was received by Neubourg Abbey, which dispatched twelve choir monks and an unspecified number of lay brothers. They arrived in 1138, but found Eckenweiher to be lacking in water and pasture space in sufficient quality and quantity,[4] and subsequently abandoned the site a few years later.[2] In 1147, the Eckenweiher monks were moved to a new site near the source of the Salzach river by the Bishop of Speyer, Günther von Henneberg. This site, Mulenbrunnen, was about 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) from Eckenweiher, was ideal for the Cistercians.[5] Maulbronn, in the hilly Stromberg region,[6] was rich in water[lower-alpha 1] and isolated, though it was also near the Roman road running from Speyer to Cannstatt. Construction of the Maulbronn Monastery complex began soon thereafter and was largely completed by 1200–01; the abbey church was consecrated in 1178 by Arnold I, Archbishop of Trier.[9]

The new abbey at Maulbronn soon began a period of steady growth thanks to its favorable location and the backing of both Bishop Henneberg, a supporter of the Cistericans, and the Hohenstaufen, at the time the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire. Bishop Henneberg waived Maulbronn's obligation to pay levies for the large amount of forest its monks had to clear in 1148. That same year, Pope Eugene III granted the Maulbronn chapter the right of patronage. This began a period of economic expansion for the monastery,[10] which aggressively pursued the acquisition of new territory,[2] starting with the nearby Füllmenbacher and Elfinger Hofs in 1152 and 1153 respectively. In 1156, Emperor Frederick I issued a decree that exempted Maulbronn from paying tithes and placed the monastery under his protection. According to Frederick I's decree, Maulbronn possessed at that time eleven farmsteads, portions of eight villages, and numerous vineyards. The monastery's holdings were again confirmed by Pope Alexander III in 1177; by then, Maulbronn owned seventeen farmsteads.[11]

The 13th and 14th centuries were periods of strife for Maulbronn,[2] though in the second half of the 13th century it was granted legal jurisdiction over its territories by Pope Alexander IV. Per the rules of the Cisterican Order, its lands had to be worked by its lay brothers. However, the number of lay brothers at Maulbronn dwindled over the 13th century, owing to conflict between them and the monks,[12] and as a result the monastery increasingly relied on hired laborers to work its land. Around 1236, the House of Enzberg became Maulbronn's patrons and vögte, or protectors. There was persistent conflict with the Enzbergs, however,[13] and one dispute in 1270 even saw the monastery temporarily suppressed. The vogtei of Maulbronn was transferred in 1372 by Emperor Charles IV to the Electoral Palatinate. This transfer drew the monastery into the power struggle between the Palatinate and the expanding County of Württemberg, and it was subsequently fortified.[2]

Maulbronn returned to being an exemplar Cistercian monastery in the 15th century,[2] as monastic discipline was reinforced in the first thirty years of the century. By the middle of the century once again enjoyed economic prosperity,[14] and construction projects at the abbey was again undertaken.[2] It paid a massive contribution to the Cîteaux Abbey, seat of the Cistercians, in 1450,[15] and then in 1464 assumed the debts of Pairis Abbey in Alsace and incorporated it as a priory.[2][14] Additionally, Maulbronn came to control Bronnbach Abbey and the convents of Mariental Abbey, Rechtenshofen Abbey, Lichtenstern, Heilsbruck Abbey, and Koenigsbruck Abbey. The number of monks at Maulbronn peaked at one hundred thirty-five in the 1460s and only dipped below one hundred again at the end of the century.[2] In 1492, Emperor Maximilian I withdrew the vogtei of Maulbronn from the Palatinate. Maximilian I additionally forbade any further fortification of the abbey, and ordered the fortifications the Elector had constructed at Maulbronn demolished.[14]

In 1504, during the War of the Succession of Landshut, Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg took Maulbronn after a seven-day siege. Ulrich subsequently had Maulbronn's vogtei transferred to him, in effect annexing the monastery and its territories into the Duchy of Württemberg. In 1525, the monastery was occupied by peasants participating in the German Peasants' War in 1525[16] and the monks expelled.[17]

Klosteramt Maulbronn

After becoming a Lutheran, Duke Ulrich ordered the dissolution of all monasteries within Württemberg's territories in 1534 and seized their properties. Maulbronn was the sole exception to this order, as it was to host monks expelled from other monasteries. In 1536, Maulbronn's abbot relocated to Pairis and the next year began legal action to reclaim Maulbronn. Following the defeat of the Protestant princes in the Schmalkaldic War, the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire decided in the Cistercians' favor at the 1548 Augsburg Interim. After the 1555 Peace of Augsburg restored religious peace in the Empire, however, Christoph, Duke of Württemberg was able to fully reform the Duchy. Following a program created by advisor Johannes Brenz, a Lutheran theologian, Christoph permanently dissolved Maulbronn Monastery and established a Protestant seminary on its grounds in 1556. The abbey's holdings were organized into a monastery district (Klosteramt), headed by a now Protestant abbot. Maulbronn's first Protestant abbot was Valentin Vannius,[18] a former monk at Maulbronn, who took office in 1558.[2] The abbot was later joined by secular administrators, who established an administrative center in the monastery complex. That center, the town of Maulbronn, was made an official administrative district (Oberamt) in the 18th century. It was elevated still further into being one of the principal administrative centers of the Kingdom of Württemberg in 1886.[19]

Two Lutheran colloquys were held at Maulbronn, in 1564 and 1576.[2]

The Thirty Years' War forced the closing of the monastery school until 1625.[20]

During the Nine Years War, Maulbronn was part of the defensive network of the Eppingen lines, built from 1695 to 1697 by Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden. The monastery bakery provided food for the workers as they toiled on the earthworks.[21]

The monastery school was taken over by the Nazi Party in 1941 but again reopened in 1945–46.[20]

UNESCO World Heritage Site

Maulbronn Monastery was inscribed in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1993.[22]

The Paradise and the fountain in the lavatorium appear on the 2013 German Bundesländer series 2 euro coin.[23] 30 million of these coins were minted in Berlin, Munich, Stuttgart, Karlsruhe, and Hamburg.[24]

As a result of the 2019-20 coronavirus pandemic, Staatliche Schlosser und Garten announced on 17 March 2020 the closure of all its monuments and cancellation of all events until 3 May.[25] Monuments began reopening in early May, from 1 May to 17 May.[26]

Maulbronn Monastery is part of the Northern Black Forest Monastery Route with Alpirsbach Abbey, Hirsau Abbey, and Reuthin Abbey.[27]

An average of 235,000 persons visit the monastery each year.[28]

Grounds and architecture

The architectural history of the Maulbronn Monastery complex is still not fully understood.[29] The monastery was constructed in the 12th century in a Romanesque style,[30] though little of the 12th century work – the portal and its original doors – has been preserved.[30] The specific style used, called the "Hirsau style", was native to Swabia and is characterized by uniform pillars and the rectangular frames around the Romanesque arches. Near the end of the 12th century the architecture of the Cistercians became influenced by Gothic architecture, and the order began disseminating it from northeastern France. An anonymous architect trained in Paris erected the first example of Gothic architecture in Germany at Maulbronn's narthex, the southern portion of its cloister, and the monks' refectory.[31][32] The Late Gothic came to Maulbronn from the late 13th century to the mid-14th century, and again in the German Romantic era of the late 19th century.[30] There is a very limited amount of Renaissance architecture at Maulbronn, represented primarily by Duke Ludwig's hunting manor.[2]

The monastery as a whole survives due mostly to the Dukes of Württemberg.[33]

The abbey church received Gothic net vaulting in the 15th century, and its furnishings mostly date to that period as well.[34]

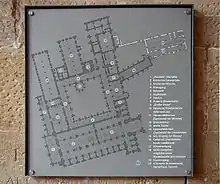

The monastery was protected by a stone wall, a drawbridge gate, and five towers.[35] The complex is still entered through the gatehouse, at its southwest corner, though the drawbridge is no longer present. The half-timber building on the back of the gatehouse was built around 1600 and the roof in 1751. Just behind the gatehouse are the pharmacy, originally an inn, and the residence of the monk responsible for giving early morning mass to guests at the monastery.[36] The interior of the building is divided into a large, open fireplace and the entrance hall.[37] Attached to the pharmacy is a 19th-century carriage house, now a museum, that stands on top of a chapel built around 1480. The foundations of the chapel's choir are still extant behind the carriage house, as are the remains of a Romanesque gate demolished in 1813. A lead pipe found here suggests that there used to be a well nearby.[36] East of the gate is the Fruchtkasten, today a concert hall. It was built in the 13th century and then totally rebuilt and enlarged in 1580 for the storage and use of wine-making equipment.[38]

To the north of the gate is the monastery's administrative and economic buildings. Along the western wall of the monastery are what used to be the blacksmithy and wheelwright's workshops. East of the blacksmithy is the former mews, which has been Maulbronn's city hall since the early 19th century. The building was converted in 1600 from its original Gothic appearance into the present Renaissance style structure. Just north of the city hall is the Haberkasten, used as a granary, and adjacent to that is the workplace and residence of the monastery's chief baker. Finally, there are three half-timber buildings. The first is the Speisemeisterei, next to the sawmill, and the third is the Bursarium, built in 1742 as the cemetery office but used as a police station and notary as of 2019. The middle building, built in 1550, was a servant's quarters.[38]

In 1588, Duke Louis III built a lustschloss over the cellar of an earlier building, likely the abbot's residence. During the existence of the Oberamt Maulbronn, Louis III's lustschloss was its administrative office. Nearby are the ruins of the Pfründhaus, where donors who had bought a life pension from the monastery resided. The building was erected in 1430 and used as a poorhouse in the 19th century until it was destroyed by fire in January 1892.[39] In the southeast corner of the complex is the Faustturm, the tower where Johann Georg Faust is alleged to have lived while staying at the monastery in 1516.[40]

Abbey

At the center of the monastery complex is the abbey, where the monks and lay brothers lived and prayed. The monastery had strict divisions between the two groups. This was so even in the church,[29] which is divided into sections for the former and the latter by a choir wall. There are two ciboriums, decorated with toads, lizards, and skulls and a number of medieval works on both sides of the choir wall.[41] In front of this wall on the lay brother's side is a large image of Christ crucified, carved around 1473 from a single block of stone.[42] At the end of the lay brother's section is the organ, installed by Gerhard Grenzing in 2013.[43] In the choir is a Madonna and Child, the Maulbronner Madonna, crafted somewhere between 1307 and 1317.[44] In the chancel below is a set of 15th century of choir stalls and abbot's chair to seat 92 monks. They were carved by an unknown master, possibly Hans Multscher, who covered them in biblical scenes and mythical creatures.[45] The frescoes within the church depict the Adoration of the Magi, the entrance of Maulbronn's founder Walter von Lomersheim into the monastery as a lay brother. Also present are the coats of arms of nobles who donated to the monastery's construction.[46] The donor chapels and vaulted Gothic roof, replacing the original flat and timber roof, were added when the church was renovated in the late 15th century.[41] The altar, likely of South German make, depicts the Passion of Jesus was once gilded and painted. Those pieces of the set that remain have since 1978 sat on a standstone slab in the chapel.[47]

The church's narthex is Germany's oldest example of Gothic architecture – the "Paradise",[48] built around 1220. The portal into the lay brothers' church contain the oldest datable doors in Germany, fashioned from fir wood in 1178. The door was decorated with wrought iron and parchment that would have been glued onto the door and painted red.[49] Immediately north of the abbey church is the cloister, the southern portion of which was built by the Master of the Paradise's workshop from 1210 to 1220.[50] Lay brothers could enter or leave the cloister from a corridor on its west side.[29] This leads to a flight of stairs to the lay brothers' dormitory, and the lay refectory on the ground floor. The groin vaults are supported by seven slender double-column pillars installed in 1869.[51] Opposite the corridor to the cloister from the lay refectory is the cellarium, now a display of stonemasonry paraphernalia.[29]

On the north side of the cloister is the lavatorium, where monks washed before meals and for ablution. The majority of the fountain within dates to 1878; only the base bowl is original. The five Gothic windows were added from 1340 to 1350 and the half-timber structure above the lavatorium was built around 1611 in a style similar to that of Heinrich Schickhardt.[52] The vaults of the lavatorium were painted with a depiction of Maulbronn's founding myth.[53] Across from the fountain house is the monks' refectory,[52] where the full brothers ate their meals and listened to a reading of the Bible. This building was possibly also built by the Master of the Paradise, as evidenced by the Early Gothic elements of its interior. The ribbing of the vaults was painted red in the 16th century.[51] The kitchen that supplied the two refectories is located between them, but arranged such to keep smoke and odors away from the rest of the monastery.[37]

Although the Cistercian Order banned heated rooms,[33] Maulbronn has a calefactory that was heated by lighting a fire in a vaulted chamber underneath the calefactory. Smoke was funneled outside and the heat rose into the calefactory through the 20 holes in its floor.[54] It was the only heated room in the monastery.[29]

.jpg.webp)

Attached to the center of the eastern side of the cloister is the chapter house, where monks could break their oaths of silence. Three pillars hold up the room's star vaults, which are clad in red frescoes from 1517. One of the captstones for the pillars depicts, unusually, eight eagles. The keystones of the vaults depict the Four Evangelists, the Lamb of God, and an angel blowing a trumpet. At the southeast corner of the chapter house is a small chapel in a bay window.[55]

A staircase on the east side of the cloister leads to the monks' dormitory.[50]

A corridor on the eastern side of the cloister goes to a Late Gothic connecting building, built by lay brother Conrad von Schmie, leading to the monastery hospital, the Ephorat. The connecting building is decorated with a mural depicting Benedict of Nursia and Bernard of Clairvaux kneeling before the Virgin Mary. From the symbolism, it is thought this space was used as a Marian chapel, a scriptorium, or a library.[50] After Maulbronn's acquisition by the Dukes of Württemberg, the hospital was renovated as the abbot's residence and gained its name from the abbot's title, "Ephorus".[39]

Water system and surroundings

As was customary with Cistercian monasteries,[56] Maulbronn stands on top of a sophisticated water management system.[57] By draining the wetlands around the monastery and digging a series of canals,[56] the monks created some 20 ponds and lakes. A local stream, the Salzach, was diverted to flow under the monastery to form its sewerage.[58] The water levels in these lakes could be controlled, allowing Maulbronn's monks to power their mill,[59] but also to raise fish and eels.[60][lower-alpha 2] In one of these ponds, the Aalkistensee, the monks could raise up to 5000 carp.[61] Much of the system remains in use and is part of Maulbronn's UNESCO inscription.[58][62] The water system has been under study by Baden-Württemberg's Office for the Preservation of Monuments since 1989.[63]

To operate their monasteries the Cistercian Order was allowed to own property such as bodies of water, vineyards, and forests. At the beginning of the 12th century, 17 monastic granges surrounded Maulbronn, operated by lay brothers.[59]

The gardens around the monastery, in its cloister and east of the church, grew fruits and medicinal herbs.[64]

Museums

The cooperage, near the gatehouse, is the visitor center. On the ground floor is a diorama of the monastery complex and on the second floor is a museum room detailing post-monastic life at Maulbronn. The nearby Frühmesserhaus displays a three-panel display made by the monks of Maulbronn documenting its foundation and attached circumstances.[65][66]

Within the monastery complex is a three-part literary museum, "Besuchen-Bilden-Schreiben",[67] operated by the state of Baden-Württemberg. The first of these, "Visit" exhibits Maulbronn's image in literature. Next is "Learn", dedicated to the monastery's use as a Protestant seminary and with a focus on alumni of the seminary such as Johannes Kepler, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Herman Hesse. Finally, "Write" showcases the works of the monks at Maulbronn and a library spanning 800 years and 50 writers.[68]

The abbey's cellarium houses a lapidarium and exhibit detailing the construction methods used at Maulbronn.[65]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maulbronn Monastery complex. |

- List of Cistercian monasteries

- Salem Abbey

- Heiligkreuztal Monastery

Notes

- The etymology of the name "Mulenbrunnen," the root of Maulbronn, reveals that the monastery was likely founded at the site of a spring and a watermill.[7][8]

- Cistercians were forbidden from eating meat, but consuming fish was allowable as they were classified as "river vegetables." Maulbronn's monks raised fish, especially mirror carp, in different bodies of water depending on their species, size, and age, and then sold them to surrounding communities.[60]

Citations

- Mueller & Stober 2009, p. 10.

- Klöster in Baden-Württemberg: Maulbronn.

- Klöster in Baden-Württemberg: Eckenweiher.

- Gillich 2017, p. 275.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 11, 12.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Maulbronn Monastery.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 11–12.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Milestones.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 10–13.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 11, 12, 21, 90.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 12, 21–22.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 14, 20, 23.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 23, 90.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, p. 16.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 16, 90.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 16–17, 24.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Valentin Vannius.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 17, 24, 90.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, pp. 26, 91.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, p. 91.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Eppingen Lines.

- Mueller & Stober 2009, p. 3.

- European Union Journal, 28 December 2013.

- Maulbronn Monastery: 2-Euro Coin.

- "Important information about the Coronavirus". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Gradual opening of our monuments". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Klosterroute Nordschwarzwald.

- City of Maulbronn: Stadtgeschichte Maulbronn.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Hermitage and Church.

- Maulbronn Monastery: History of Design.

- Burton & Kerr 2011, pp. 77, 78–79.

- Maulbronn Monastery: World Heritage Site.

- Jeep 2001, p. 508.

- Jeep 2001, p. 507.

- Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 75.

- Maulbronn Monastery: West Entrance.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Kitchens.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Courtyard and Outbuildings.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Eastern Courtyard.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Doctor Faustus.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Monastery Church.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Crucifix.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Grenzing Organ.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Madonna.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Choir Stalls.

- Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 81.

- Maulbronn Monastery: High altar reliefs.

- Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 79.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Paradise.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Cloister.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Refectories.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Fountain House.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Founding Legend.

- Kinder 2002, p. 279.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Chapter House.

- Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 69.

- Baden-Württemberg: Kloster Maulbronn.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Water Management.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Surrounding Area.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Fish Farming.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Cookbook.

- UNESCO: Maulbronn Monastery Complex.

- Baden-Württemberg: UNESCO-Welterbestätte Kloster Maulbronn.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Gardens.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Monastery Museums.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Founders Panel.

- City of Maulbronn: Besuchen-Bilden-Schreiben.

- Maulbronn Monastery: Literary Museum.

References

- Burton, Janet B.; Kerr, Julie (2011). The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Monastic orders. Volume 4 (Illustrated ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836674.

- Gillich, Ante (2017). "Das Wassersystem des Klosters Maulbronn: Ein Projekt zur Bestandserfassung mit hochaufgelösten Laserscandaten". Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg (in German). Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- Jeep, John M. (2001). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780824076443.

- Kinder, Terryl M. (2002). Cistercian Europe: Architecture of Contemplation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802838872.

- Mueller, Carla; Stober, Karin (2009). Maulbronn Monastery. Deutscher Kunstverlag. ISBN 978-3-422-02054-2.

Online references

- "New national side of euro coins intended for circulation" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. European Union. 28 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- "Maulbronn Monastery Complex". UNESCO World Heritage. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- German Federal, state, and municipal governments

- "Kloster Maulbronn". Baden-Württemberg Office for the Preservation of Monuments. State of Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "UNESCO-Welterbestätte Kloster Maulbronn: Die Erforschung des Wassersystems". Baden-Württemberg Office for the Preservation of Monuments. State of Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Rückert, Peter. "Zisterzienserkloster Eckenweiher - Geschichte". Klöster in Baden-Württemberg. Baden-Württemberg State Archive. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Rückert, Peter. "Zisterzienserabtei Maulbronn - Geschichte". Klöster in Baden-Württemberg. Baden-Württemberg State Archive. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Maulbronn Monastery". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Monastery". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Western Entrance". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Monastery Courtyard with Outbuildings". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Hermitage and the Monastery Church". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "The Paradise". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Monastery". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Cloister". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Fountain House". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Chapter House". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Refectories". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Kitchens". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Eastern Courtyard". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Gardens". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Maulbronn Madonna". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Choir Stalls". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The High Altar Reliefs". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Maulbronn Crucifix". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Founders Panel". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Monastery Museums". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Visit — Learn — Write". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Klosterroute Nordschwarzwald". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "Milestones". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Valentin Vannius". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "The Founding Legend". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Doctor Faustus". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "History of Design". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Eppingen Lines". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Bernhard Buchinger's Cookbook". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Area Around the Monastery". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Fish Farming". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Water Management". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "World Heritage Site Maulbronn". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Grenzing Organ". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Bell". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The 2-Euro Coin". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Stadtgeschichte Maulbronn" (in German). City of Maulbronn. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "Besuchen-Bilden-Schreiben. Das Kloster Maulbronn und die Literatur" (in German). City of Maulbronn. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

External links

- Official website (in English)

- UNESCO entry for Maulbronn Monastery Complex (in English)

- Literaturland Baden-Württemberg entry for the literature museum (in German)