Mary of Burgundy

Mary (French: Marie; Dutch: Maria; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), Duchess of Burgundy, reigned over the Burgundian State, now mainly in France and the Low Countries, from 1477 until her death in a riding accident at the age of 25.

| Mary | |

|---|---|

Portrait, attributed to Michael Pacher, c. 1490 | |

| Duchess of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482 |

| Predecessor | Charles the Bold |

| Successor | Philip the Handsome |

| Co-ruler | Maximilian |

| Born | 13 February 1457 Brussels, Brabant, Burgundian Netherlands |

| Died | 27 March 1482 (aged 25) Wijnendale Castle, Flanders, Burgundian Netherlands |

| Burial | Bruges, Flanders |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Philip I of Castile Margaret, Duchess of Savoy |

| House | Valois-Burgundy |

| Father | Charles the Bold |

| Mother | Isabella of Bourbon |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

As the only child of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and his wife Isabella of Bourbon, she inherited the Burgundian lands upon the death of her father in the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477.[1] She spent most of her reign defending her birthright; in order to counter Louis XI's appetite for her lands, she married Maximilian of Habsburg, who long after her death became Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. The marriage was a turning point in European politics, leading to a French–Habsburg rivalry that would endure for centuries.

Early years

Mary of Burgundy was born in Brussels at the ducal castle of Coudenberg, to Charles the Bold, then known as the Count of Charolais, and his wife Isabella of Bourbon. Her birth, according to the court chronicler Georges Chastellain, was attended by a clap of thunder ringing from the otherwise clear twilight sky. Her godfather was Louis, Dauphin of France, in exile in Burgundy at that time; he named her for his mother Marie of Anjou. Reactions to the child were mixed: the baby's grandfather, Duke Philip the Good, was unimpressed, and "chose not to attend the [baptism] as it was only for a girl", whereas her grandmother Isabella of Portugal was delighted at the birth of a granddaughter.[2] Her illegitimate aunt Anne was assigned to be responsible for Mary's education and assigned Jeanne de Clito to be her governess, Jeanne remained a constant friend to Mary later in life and was one of her most constant companions.

Heiress presumptive

Philip the Good died in 1467 and Mary's father assumed control of the Burgundian State. Since her father had no living sons at the time of his accession, Mary became his heir presumptive. Her father controlled a vast and wealthy domain made up of the Duchy of Burgundy, the Free County of Burgundy, and the majority of the Low Countries. As a result, her hand in marriage was eagerly sought by a number of princes. The first proposal was received by her father when she was only five years old, in this case to marry the future King Ferdinand II of Aragon. Later she was approached by Charles, Duke of Berry; his older brother, King Louis XI of France, was intensely annoyed by Charles's move and attempted to prevent the necessary papal dispensation for consanguinity.

As soon as Louis succeeded in producing a male heir who survived infancy, the future King Charles VIII of France, Louis wanted him to be the one to marry Mary, even though he was thirteen years younger than Mary. Nicholas I, Duke of Lorraine, was a few years older than Mary and controlled a duchy that lay alongside Burgundian territory, but his plan to combine his domain with hers was ended by his death in battle in 1473.

Reign

Mary assumed the rule of her father's domains upon his defeat in battle and death on 5 January 1477. King Louis XI of France seized the opportunity to attempt to take possession of the Duchy of Burgundy proper and also the regions of Franche-Comté, Picardy and Artois.

The king was anxious that Mary should marry his son Charles and thus secure the inheritance of the Low Countries for his heirs, by force of arms if necessary. Burgundy, fearing French military power, sent an embassy to France to negotiate a marriage between Mary and the six-year-old Dauphin (later King Charles VIII), but returned home without a betrothal; the French king's demands of cession of territories to the French crown were deemed unacceptable.[3]

The Great Privilege

Mary was compelled to sign a charter of rights known as the Great Privilege in Ghent on 10 February 1477 on the occasion of her formal recognition as her father's heir (the "Joyous Entry"). Under this agreement, the provinces and towns of Flanders, Brabant, Hainaut, and Holland recovered all the local and communal rights that had been abolished by the decrees of the dukes of Burgundy in their efforts to create a centralised state on the French model out of their disparate holdings in the Low Countries. In particular, the Parliament of Mechelen (established formally by Charles the Bold in 1470) was abolished and replaced with the pre-existing authority of the Parliament of Paris, which was considered an amenable counterweight to the encroaching centralisation undertaken by both Charles the Bold and Philip the Good. The duchess also had to undertake not to declare war, make peace, or raise taxes without the consent of these provinces and towns and only to employ native residents in official posts.

Such was the hatred of the people for the old regime that in spite of the duchess's entreaties, two of her father's most influential councilors, the Chancellor Hugonet and the Sire d'Humbercourt, were executed in Ghent after it was discovered that they were in correspondence with the king of France.

Marriage

Mary soon made her choice among the many suitors for her hand by selecting Archduke Maximilian of Austria, the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, who became her co-ruler.[4] The marriage took place at Ghent on 19 August 1477.[5] Mary's marriage into the House of Habsburg initiated two centuries of contention between France and the Habsburgs, a struggle that climaxed with the War of the Spanish Succession in the years 1701–1714.

In the Netherlands, affairs now went more smoothly; the French aggression was temporarily checked, and internal peace was in large measure restored.

Death and legacy

In 1482, a falcon hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle was organised by Adolph of Cleves, Lord of Ravenstein, who lived in the castle. Mary loved riding and was hunting with Maximilian and knights of the court when her horse tripped, threw her in a ditch, and then landed on top of her, breaking her back. She died several weeks later on 27 March from internal injuries, having made a detailed will. She was buried in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges on 3 April, 1482.

Her two-year-old daughter, Margaret of Austria, was sent in vain to France, to marry the Dauphin, in an attempt to please Louis XI and persuade him not to invade the territories owned by Mary.

Louis was swift to re-engage hostilities with Maximilian and forced him to agree to the Treaty of Arras of 1482, by which Franche-Comté and Artois passed for a time to French rule, only to be recovered by the Treaty of Senlis of 1493, which established peace in the Low Countries. Mary's marriage into the House of Habsburg proved to be a disaster for France because the Burgundian inheritance later brought it into conflict with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire.

Family

Mary's son Philip succeeded to her dominions under the guardianship of his father.

Her children were as follows:

- Philip the Handsome (22 July 1478 – 25 September 1506), who succeeded his mother as Philip IV of Burgundy and became Philip I of Castile through his marriage to Joanna of Castile (known to history as "Juana la Loca").[6]

- Margaret (10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530), married firstly to Juan, Prince of Asturias, the son and heir of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, and secondly to Philibert II, Duke of Savoy.[7]

- Francis (2 September 1481 – 26 December 1481).

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Mary of Burgundy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Titles

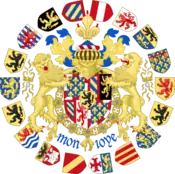

Arms before 1477

Arms before 1477.svg.png.webp) Arms after 1477

Arms after 1477

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Burgundy

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Burgundy 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Lothier

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Lothier 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Brabant

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Brabant 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Limburg

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Limburg 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Luxemburg

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Luxemburg 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Guelders

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Guelders 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Flanders

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Flanders 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Artois

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Artois 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess Palatine of Burgundy

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess Palatine of Burgundy 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Hainault

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Hainault 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Holland

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Holland 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zeeland

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zeeland.svg.png.webp) 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Namur

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Namur 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zutphen

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zutphen 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Margravine of Antwerp

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Margravine of Antwerp

See also

- Dukes of Burgundy family tree

- Other politically important horse accidents

- Duchesse de Bourgogne beer

- Hours of Mary of Burgundy

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mary of Burgundy. |

- Vaughan 2004, p. 127.

- Taylor 2002, p. ?.

- Koenigsberger 2001, p. 49.

- Kendall 1971, p. 319.

- Armstrong 1957, p. 228.

- Ingrao 2000, p. 4.

- Ward, Prothero & Leathes 1934, p. table 32.

Sources

- Armstrong, C.A.J. (1957). "The Burgundian Netherlands, 1477-1521". In Potter, G.R. (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History. I. Cambridge at the University Press. ISBN 978-0521045414.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ingrao, Charles W. (2000). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108499255.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI. W.W. Norton Co. Inc. ISBN 978-0393302608.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koenigsberger, H. G. (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521803304.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Aline S. (2002). Isabel of Burgundy. Rowman & Littlefield Co. ISBN 978-1568332277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vaughan, Richard (2004). Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851159188.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ward, A.W.; Prothero, G.W.; Leathes, Stanley, eds. (1934). The Cambridge Modern History. XIII. Cambridge at the University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Mary of Burgundy Cadet branch of the House of Valois Born: 13 February 1457 Died: 27 March 1482 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles the Bold |

Duchess of Brabant, Limburg, Lothier, Luxemburg and Guelders; Margravine of Namur; Countess Palatine of Burgundy; Countess of Artois, Flanders, Charolais, Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland and Zutphen 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482 with Maximilian since 19 August 1477 |

Succeeded by Philip the Handsome |