Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea case

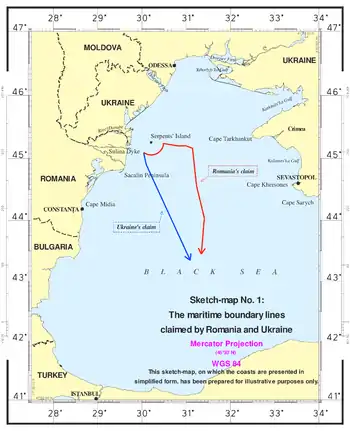

The Case concerning maritime delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v Ukraine) [2009] ICJ 3 was a decision of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). On September 16, 2004, Romania brought its case to the court after unsuccessful bilateral negotiations. On February 3, 2009, the court handed down its verdict, establishing a maritime boundary including the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones for Romania and Ukraine.

Facts

In 1997, Romania and Ukraine signed a treaty in which both states "reaffirm that the existing border between them is inviolable and therefore, they shall refrain, now and in future, from any attempt against the border, as well as from any demand, or act of, seizure and usurpation of part or all the territory of the Contracting Party".[1] Both sides agreed that if no resolution on maritime borders could be reached within two years, either side could seek a final ruling from the International Court of Justice. Ten million tonnes of oil and a billion cubic meters of natural gas deposits were discovered under the seabed nearby.

BP and Royal Dutch/Shell signed prospect contracts with Ukraine, and Total contracted with Romania. The Austrian OMV (the owner of Romania's largest oil company, Petrom) signed a contract with Naftogas of Ukraine and Chornomornaftogaz to participate in an auction of concession rights to the area.

Because of its location, Snake Island affected the maritime boundary between the two countries. If Snake Island was an island, its continental shelf area would be considered Ukrainian waters. If it was an islet, in accordance with international law, the maritime boundary between Romania and Ukraine would not take it into consideration. Romania claimed that Ukraine was developing Snake Island to prove it was an island, rather than an islet.[2]

Court hearings

On 16 September 2004, Romania brought a case against Ukraine to the International Court of Justice, as part of a dispute over the maritime boundary between the two states in the Black Sea, and claimed that Snake island had no socioeconomic significance.[3] Islands are generally considered when boundaries are delimited by the states themselves or by a third party, such as the ICJ. Depending on individual circumstances, islands may theoretically have full, partial or no effect on determinations of entitlement to maritime areas.

However, in practice, even islets are often respected in maritime delimitation. For example, Aves Island was considered in the United States – Venezuela Maritime Boundary Treaty despite its small size and the fact that it was uninhabited. Most states do not distinguish between islands, under Article 121(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, claim the shelf as an EEZ for all of their islands. Examples include the UK's Rockall, Japan's Okinotorishima, the US's Hawaiian Islands and a number of uninhabited islands along the equator, France's Clipperton and other islands and Norway's Jan Mayen.

Decisions by international courts, tribunals and other third-party dispute-resolution bodies have been less uniform. Although under Article 121(3), rocks are taken into account in delimiting maritime boundaries, they may be overlooked, discounted or enclaved if they have an inequitable distorting effect in light of their size and location. Even if such islands are not discounted, their influence on the delimitation may be minimal. Therefore, existing decisions have not reached the level of uniformity necessary for a rule of law.

Until this dispute, there had been no third-party international review of a particular feature's status as an Article 121(3) rock or Article 121(2) island, and the ICJ's decision was difficult to predict. If it declared Snake Island an island, in delimiting the maritime zones, the ICJ could consider "special" or "relevant" circumstances and give Snake Island full, partial or no effect on the boundary. On September 19, 2008, the ICJ closed its public hearing.[4][5]

Judgment

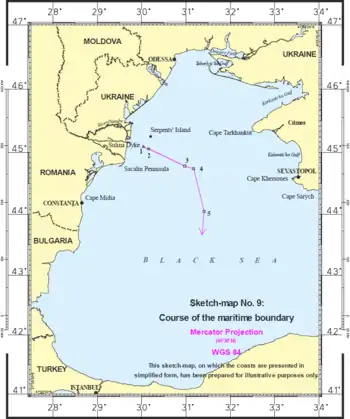

The court delivered its judgment on February 3, 2009,[6] dividing the Black Sea with a line between the claims of each country. On the Romanian side, the ICJ found that the landward end of the Sulina dyke, not the manmade end, should be the basis for the equidistance principle. The court noted that a dyke has a different function from a port, and only harbor works form part of the coast.[7]

On the Ukrainian side, the court found that Snake Island did not form part of Ukraine's coastal configuration, explaining that "to count [Snake] Island as a relevant part of the coast would amount to grafting an extraneous element onto Ukraine's coastline; the consequence would be a judicial refashioning of Geography". The ICJ concluded that Snake Island "should have no effect on the delimitation in this case, other than that stemming from the role of the 12-nautical-mile arc of its territorial sea".[7] While the judgment drew a line that was equitable for both parties, Romania received nearly 80% of the disputed area, allowing it to exploit a significant but undetermined portion of an estimated 100 billion cubic meters of deposits and 15 million tonnes of petrol under the seabed.[8]

However, according to UN International Court Ukrainian commissioner Volodymyr Vasylenko, nearly all the oil and gas reserves are concentrated in the seabed that went to Ukraine.[9]

Ukrainian President Viktor Yuschenko considered the ruling "just and final" and hoped that it would open "new opportunities for further fruitful cooperation in all sectors of the bilateral cooperation between Ukraine and Romania".[10]

References

- The Romania-Ukraine Treaty (1997) is available in Romanian and English in the materials submitted by Romania to the International Court of Justice and it is available in Ukrainian from the Ukrainian parliament website .

- Ruxandra Ivan (2012). New Regionalism Or No Regionalism?: Emerging Regionalism in the Black Sea Area. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4094-2213-6.

- "Romania brings a case against Ukraine to the Court in a dispute concerning the maritime boundary between the two States in the Black Sea" (PDF). International Court of Justice. September 16, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2008.

- "Conclusion of the public hearings - Court begins its deliberation" (PDF). International Court of Justice. September 19, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016.

- "Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- "The Court establishes the single maritime boundary delimiting the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones of Romania and Ukraine" (PDF). International Court of Justice. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2009.

- "Case Concerning Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine). Judgment" (PDF). International Court of Justice. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2015.

- EU's Black Sea border set in stone, EUobserver, February 3, 2009

- Ukraine gets bulk of oil, gas reserves in delimitation dispute with Romania, says commissioner to international court Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (February 3, 2009)

- Yuschenko: UN International Court Of Justice's Decision On Delimitation Of Black Sea Shelf Between Ukraine And Romania Just Archived 2009-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainian News Agency (February 5, 2009)

Sources

- Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine): A Commentary by Alex Oude Elferink, 27 Mar 2009, The Hague Justice Portal

- Coalter G. Lathrop (July 22, 2009) "Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine)". American Journal of International Law, Vol. 103. SSRN 1470697

- Clive Schofield (2012). "Islands or Rocks, Is that the Real Question? The Treatment of Islands in the Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries". In Myron H. Nordquist; John Norton Moore; Alfred H.A. Soons; Hak-So Kim (eds.). The Law of the Sea Convention: US Accession and Globalization. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 322–340. ISBN 978-90-04-20136-1.