Mapuche polygamy

Polygamy has a long history among the Mapuche people of southern South America. Wives that share the same husband are often relatives, such as sisters, who live in the same community.[1] Having the same husband does not imply women belong to the same household.[1] Mapuche polygamy has no legal recognition in Chile.[1] This puts women who are not legally married to their husband at disadvantage to any legal wife in terms of securing inheritance.[1] It is thought that present-day polygamy is much less common than it once was, in particularly compared with the time before the Occupation of Araucanía (1861–1883) when Araucanía lost its autonomy.[1] Albeit chiefly rural, Mapuche polygamy has also been reported in the low-income peripheral communes of Santiago.[2] Mapuche polyandry is rare but not unheard of,[3] and in these cases the men are often brothers.[4][upper-alpha 1]

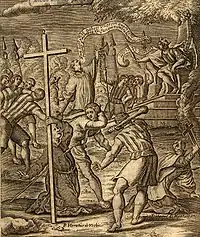

In Colonial Chile this custom caused tensions with the Catholic Church as polygamy is explicitly prohibited in the church's teaching. A notable incident involving polygamy happened in December 14, 1612 when Mapuche Toqui Anganamón had three Jesuit missionaries killed in retaliation for the Spanish protecting his two fugitive wives and two of his daughters.[6][7] The Spanish justified their protection of Angamón's fugitive wives and daughters by their rejection of polygamy.[6] This was a clear setback for Father Luis de Valdivia's effort to bring peace and Christianize Mapuches through the policy of Defensive War.[6] In later colonial times and in the early republic some officials, known as capitanes de amigos, that were allowed to live among friendly Mapuche tribes south of the frontier often married Mapuche women, some going as far as also engaging in polygamy.[8] According to historian José Bengoa, Mapuche defense of polygamy was a cornerstone of their rejection of Christianity.[1] Polygamy for long time occupied an important role in war-torn Araucanía, where male population levels were unstable.[1][upper-alpha 2] Also, according to historian G. Boccara given the tradition of raptio that existed among warring Mapuches, a man that was monogamous or had few wives was understood as being a poor warrior.[10] During the Arauco War and afterwards, polygamy enabled Mapuche chiefs to establish alliances through marriage, with the acquisition of more wives widening the possibilities for alliances.[1] In general terms polygamy enables to increase the amount of reciprocal relationships for individual Mapuche men.[11]

Footnotes

- According to anthropologist Ana Gabriel Millaleo polyandry is wholly absent in the "great Mapuche chronicles" and in apparent contradiction to the renewal of warrior ethos (weichan) promoted by militant organizations such as Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco.[5][4]

- Chronicler Alonso González de Nájera wrote that during the Destruction of the Seven Cities, Mapuches killed more than 3,000 Spaniards, and took over 500 women as captives.[9] While some of these women were later rescued, others were set free only through agreements established by the Parliament of Quillín in 1641.[9] Some Spanish women became accustomed to life among the Mapuche and stayed voluntarily.[9] The Spanish understood this phenomenon as a result either of women's weak character or their genuine shame over having been abused.[9] Women in captivity gave birth to a large number of mestizos, who were rejected by the Spanish but accepted among the Mapuches.[9] These women's children may have had a significant demographic impact in the Mapuche society, which was long ravaged by war and epidemics.[9]

References

- Rausell, Fuencis (June 1, 2013). "La poligamia pervive en las comunidades indígenas del sur de Chile". La Información (in Spanish). Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Millaleo 2018, p. 133

- Millaleo 2018, p. 296

- Millaleo 2018, p. 298

- Millaleo 2018, p. 297

- Pinto Rodríguez, Jorge (1993). "Jesuitas, Franciscanos y Capuchinos italianos en la Araucanía (1600–1900)". Revista Complutense de Historia de América (in Spanish). 19: 109–147.

- "Misioneros y mapuche (1600-1818)". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- "Tipos fronterizos". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Guzmán, Carmen Luz (2013). "Las cautivas de las Siete Ciudades: El cautiverio de mujeres hispanocriollas durante la Guerra de Arauco, en la perspectiva de cuatro cronistas (s. XVII)" [The captives of the Seven Cities: The captivity of creole women during the Arauco's War, from the insight of four chroniclers (17th century)]. Intus-Legere Historia (in Spanish). 7 (1): 77–97. doi:10.15691/07176864.2014.0.94.

- Millaleo 2018, p. 41

- Millaleo 2018, p. 39

- Bibliography

- Millaleo Hernández, Ana Gabriel (2018). Poligamia mapuche / Pu domo ñi Duam (un asunto de mujeres): Politización y despolitización de una práctica en relación a la posición de las mujeres al interior de la sociedad mapuche (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: University of Chile.