Mangrove horseshoe crab

The mangrove horseshoe crab (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda), also known as the round-tailed horseshoe crab,[2] is a chelicerate arthropod found in tropical marine and brackish waters in India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, China and Hong Kong. It may also occur in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and the Philippines, but confirmed records are lacking.[3]

| Mangrove horseshoe crab | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | Xiphosura |

| Family: | Limulidae |

| Genus: | Carcinoscorpius Pocock, 1902 |

| Species: | C. rotundicauda |

| Binomial name | |

| Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Latreille, 1802) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Despite their name, horseshoe crabs are more closely related to spiders and scorpions (all are in the subphylum Chelicerata) than to crabs. Recent phylogenetic analysis suggests that horseshoe crabs may themselves be arachnids.[4] The mangrove horseshoe crab is the only species in the genus Carcinoscorpius. There are four extant (living) species of horseshoe crab. The biology, ecology and breeding patterns of C. rotundicauda and the two other Asian horseshoe crab species, Tachypleus gigas and Tachypleus tridentatus, have not been as well documented as those of the North American species Limulus polyphemus. All four extant species of horseshoe crabs are anatomically very similar, but C. rotundicauda is considerably smaller than the others and the only species where the cross section of the tail (telson) is rounded instead of essentially triangular.[5]

Evolutionary history

Horseshoe crabs are commonly known by biologists around the world as a living fossil because they have remained practically unchanged in terms of shape and size for millions of years. Although their physiology has changed over the years, their typical three piece exoskeleton, consisting of a prosoma, opisthosoma, and telson, has remained since the mid-Paleozoic era.[6] Fossils of horseshoe crabs that have been dated to over 400 million years ago look almost identical to those species that are still alive today.[7] The long existence of this body plan suggests its success. It is estimated that the American species of horseshoe crab diverged from the three Indo-Pacific species approximately 135 million years ago.[6]

Anatomy

_(6707310189).jpg.webp)

The basic body plan of a horseshoe crab consists of three parts: the prosoma, the opisthosoma and the tail (telson). The prosoma is the large, dome-shaped frontal part at the carapace. The smaller rear carapace with spines on the edge is the opisthosoma. The rear extension that looks like a spike is the telson, which is commonly described as the tail.[8] Uniquely among the horseshoe crabs, the cross section of the tail of the mangrove horseshoe crab is rounded. It is essentially triangular in the other species.[5][9] The tail is used to turn itself right side up when overturned.[7]

The mangrove horseshoe crab is the smallest of the four living species of horseshoe crabs.[5] Like the other species, females grow larger than males. On average in Peninsular Malaysia, females are about 30.5–31.5 cm (12.0–12.4 in) long, including a tail that is about 16.5–19 cm (6.5–7.5 in), and their carapace (prosoma) is about 16–17.5 cm (6.3–6.9 in) wide. In comparison, the average for males is about 28–30.5 cm (11.0–12.0 in) long, including a tail that is about 15–17.5 cm (5.9–6.9 in), and their carapace is about 14.5–15 cm (5.7–5.9 in) wide.[10] There are significant geographic variations in the size, but this does not follow a clear north–south or east–west pattern. Those from West Bengal in India average somewhat smaller than those from Peninsular Malaysia, with a carapace width of about 16 cm (6.3 in) and 14 cm (5.5 in) in females and males respectively. Elsewhere it averages even smaller, with the smallest reported from the Balikpapan and Belawan regions in Indonesia where the carapace width of females is about 13 cm (5.1 in) and in males 11 cm (4.3 in).[9] The largest females of the species may reach up to 40 cm (16 in) in length, including the tail.[5]

Uncommon for chelicerates, horseshoe crabs have two compound eyes. The main function of these compound eyes is to find a mate. In addition, they have two median eyes, two rudimentary lateral eyes, and an endoparietal eye on their carapace and two ventral eyes located on the underside by the mouth. Scientists believe the two ventral eyes aid in the orientation of the horseshoe crab when swimming.[5] Each individual has six pairs of appendages. The first pair, the chelicerae, are relatively small and placed in front of the mouth. They are used to place food in it. The remaining five pairs of legs are placed on either side of the mouth and are used for walking/pushing. These are the pedipalps (first pair) and the pusher legs (remaining four pairs).[5][9] Most of the appendages have straight, scissor-like claws, but in males the first and second pair of walking legs have strongly hooked "scissors", which are used for grasping the female during mating.[9] Located behind their legs are book gills. These gills are used for propulsion to swim and to exchange respiratory gases.[5]

Distribution and habitat

This species occurs only in Asia around the Indo-West Pacific region where the climate is tropical or subtropical.[11] These horseshoe crabs can be found to exist throughout southeast Asia in shallow waters with soft, sandy bottoms or extensive mud flats. The mangrove horseshoe crab is benthopelagic, spending most of its life close to or at the bottom of a body of their brackish, swampy water habitat, such as mangroves.[11] This is the habitat for which it gains its common name: mangrove horseshoe crab. Scientists have studied the distribution of mangrove horseshoe crabs in Hong Kong specifically. The researchers noted their abundance on the beaches of Hong Kong before the sharp decline in population over the past ten years. In the study, they found an uneven distribution of the horseshoe crabs throughout Hong Kong, with a greater abundance found in the western waters. They predict this unevenness is due to the estuarine hydrography in the western waters, influenced by the Pearl River. They also found that T. tridentatus can coexist in the same habitat as the mangrove horseshoe crab.[12]

Diet

Mangrove horseshoe crabs are selective benthic feeders, feeding mainly on insect larvae, small fish, oligochaetes, small crabs and thin-shelled bivalves.[13] Lacking jaws, it grinds up the food with bristles on its legs and places it in its mouth using its chelicerae. The ingested food then enters the cuticle-lined oesophagus and then the proventriculus. The proventriculus is made up of a crop and a gizzard. The crop can expand to fit the ingested food, while the gizzard grinds the food into a pulp.[5] Studies have found that mangrove horseshoe crabs have a strong preference for insect larvae over the other organisms on which it also feeds.[13]

Mating biology

In the spring, horseshoe crabs migrate from the deeper water to the shallow, muddy areas. Nesting usually follows the cycle of the high tide of the full and new moons. During the mating period, the males will follow and cling to the backs of their potential mates using modified prosomal appendages for long periods of time before the egg-laying has occurred. Horseshoe crab species with low spawning densities and 1:1 sex ratios, such as the mangrove horseshoe crab, are found to be monogamous. In addition, the female does not choose her mate. Males find their female mates with the use of visual and chemoreceptive signals.[14] Once a mate is found, the female digs a hole and lays the eggs while the male externally fertilizes them. Once the eggs are laid, the male and female go back to the ocean, and the eggs develop on their own.[14] Their eggs are large, and after a couple weeks, the eggs hatch into miniature versions of the adults.The females lay about 3500 of them.

Mangrove horseshoe crabs in Singapore breed from August to April. Juveniles grow about 33% bigger each time they molt, and it takes the juveniles about five molts to grow from 2 centimetres (0.79 in) to adult size.[15]

Use by humans

.jpg.webp)

Thousands of the horseshoe crabs are caught by local fishermen.[16] While the crabs have very little flesh, their roe is prized as a delicacy, in Thailand most commonly served as a salad called yam khai maeng da (ยำไข่แมงดา).[17]

There have occasionally been cases of food poisonings or even deaths after consuming the crabs as they were misidentified as another horseshoe crab species, Tachypleus gigas. Unlike larger T. gigas, C. rotundicauda is known to often contain lethal tetradotoxin.[18]

In addition, horseshoe crabs are prized for their blue blood, as it is widely used in biomedical sciences for the development of drugs for diseases like mental exhaustion and gastroenteritis. The blood contains a chemical called Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) that can be used to detect germs and their endotoxins.[16]

References

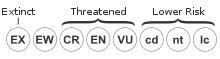

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T3856A10123044. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T3856A10123044.en.

- "Identification guide". Horseshoe Crab monitoring site. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Stine Vestbo; Matthias Obst; Francisco J. Quevedo Fernandez; Itsara Intanai; Peter Funch (2018). "Present and Potential Future Distributions of Asian Horseshoe Crabs Determine Areas for Conservation". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5 (164): 1–16. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00164.

- Sharma, Prashant P.; Ballesteros, Jesús A. (2019). "A Critical Appraisal of the Placement of Xiphosura (Chelicerata) with Account of Known Sources of Phylogenetic Error". Systematic Biology. 68 (6): 896–917. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz011. PMID 30917194.

- "About the Species". The Horseshoe Crab. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Rudkin, D. M.; Young, G. A. (2009). "Horseshoe Crabs – an Ancient Ancestry Revealed". In Tanacredi, John T.; Botton, Mark L.; Smith, David (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. pp. 25–44. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-89959-6_2. ISBN 978-0-387-89958-9.

- Kelvin K. P. Lim; Dennis H. Murphy; T. Morgany; N. Sivasothi; Peter K. L. Ng; B. C. Soong; Hugh T. W. Tan; K. S. Tan & T. K. Tan (2001). Peter K. L. Ng & N. Sivasothi (eds.). "Mangrove horseshoe crab, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, family Limulidae". A Guide to Mangroves of Singapore 1. Guide to the Mangroves of Singapore. Singapore Science Centre.

- Helen M. C. Chiu & Brian Morton (2003). "The morphological differentiation of two horseshoe crab species, Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Xiphosura), in Hong Kong with a regional Asian comparison". Journal of Natural History. 37 (19): 2369–2382. doi:10.1080/00222930210149753.

- Koichi Sekiguchi; Carl N. Shuster Jr (2009). "Limits on the Global Distribution of Horseshoe Crabs (Limulacea): Lessons Learned from Two Lifetimes of Observations: Asia and America". In Tanacredi, John T.; Botton, Mark L.; Smith, David (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Springer. pp. 5–24. ISBN 978-0-387-89959-6.

- T.C. Srijaya; P.J. Pradeep; S. Mithun; A. Hassan; F. Shaharom; A. Chatterji (2010). "A New Record on the Morphometric Variations in the Populations of Horseshoe Crab (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda Latreille) Obtained from Two Different Ecological Habitats of Peninsular Malaysia". Our Nature. 8 (1): 204–211. doi:10.3126/on.v8i1.4329.

- "Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, mangrove horseshoe crab". SeaLifeBase. 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Helen M. C. Chiu & Brian Morton (1999). "The distribution of horseshoe crabs (Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda) in Hong Kong". In Brian Morton (ed.). Asian Marine Biology. 16. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 185–196. ISBN 978-962-209-520-5.

- H. Zhou & Brian Morton (2004). "The diets of juvenile horseshoe crabs, Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Xiphosura), from nursery beaches proposed for conservation in Hong Kong". Journal of Natural History. 38 (15): 1915–1925. doi:10.1080/0022293031000155377.

- Jennifer H. Mattei; Mark A. Beekey; Adam Rudman & Alyssa Woronik (2010). "Reproductive behavior in horseshoe crabs: does density matter?" (PDF). Current Zoology. 56 (5): 634–642. doi:10.1093/czoolo/56.5.634. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- Lesley Cartwright-Taylor; Julian Lee & Chia Chi Hsu (2019). "Population structure and breeding pattern of the mangrove horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda in Singapore". Aquatic Biology. 8: 61–69. doi:10.3354/ab00206.

- Bibhuti Pati (June 24, 2008). "Horseshoe crabs galloping towards extinction". Merinews. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "~Horseshoe Crab Egg Salad Recipe, ยำไข่แมงดา~". 2013-01-28.

- Kanchanapongkul, J.; Krittayapoositpot, P. (June 1995). "An epidemic of tetrodotoxin poisoning following ingestion of the horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda". The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 26 (2): 364–367. ISSN 0125-1562. PMID 8629077.

External links

Media related to Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda at Wikimedia Commons