Magic hypercube

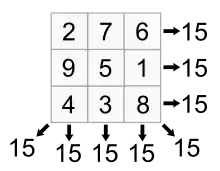

In mathematics, a magic hypercube is the k-dimensional generalization of magic squares and magic cubes, that is, an n × n × n × ... × n array of integers such that the sums of the numbers on each pillar (along any axis) as well as on the main space diagonals are all the same. The common sum is called the magic constant of the hypercube, and is sometimes denoted Mk(n). If a magic hypercube consists of the numbers 1, 2, ..., nk, then it has magic number

- .

For k = 4, a magic hypercube may be called a magic tesseract, with sequence of magic numbers given by OEIS: A021003.

The side-length n of the magic hypercube is called its order. Four-, five-, six-, seven- and eight-dimensional magic hypercubes of order three have been constructed by J. R. Hendricks.

Marian Trenkler proved the following theorem: A p-dimensional magic hypercube of order n exists if and only if p > 1 and n is different from 2 or p = 1. A construction of a magic hypercube follows from the proof.

The R programming language includes a module, library(magic), that will create magic hypercubes of any dimension with n a multiple of 4.

Perfect and Nasik magic hypercubes

If, in addition, the numbers on every cross section diagonal also sum up to the hypercube's magic number, the hypercube is called a perfect magic hypercube; otherwise, it is called a semiperfect magic hypercube. The number n is called the order of the magic hypercube.

The above definition of "perfect" assumes that one of the older definitions for perfect magic cubes is used. See Magic Cube Classes. The Universal Classification System for Hypercubes (John R. Hendricks) requires that for any dimension hypercube, all possible lines sum correctly for the hypercube to be considered perfect magic. Because of the confusion with the term perfect, nasik is now the preferred term for any magic hypercube where all possible lines sum to S. Nasik was defined in this manner by C. Planck in 1905. A nasik magic hypercube has 1/2(3n − 1) lines of m numbers passing through each of the mn cells.

Notations

in order to keep things in hand a special notation was developed:

- : positions within the hypercube

- : vector through the hypercube

Note: The notation for position can also be used for the value on that position. Then, where it is appropriate, dimension and order can be added to it, thus forming: n[ki]m

As is indicated 'k' runs through the dimensions, while the coordinate 'i' runs through all possible values, when values 'i' are outside the range it is simply moved back into the range by adding or subtracting appropriate multiples of m, as the magic hypercube resides in n-dimensional modular space.

There can be multiple 'k' between bracket, these can't have the same value, though in undetermined order, which explains the equality of:

Of course given 'k' also one value 'i' is referred to.

When a specific coordinate value is mentioned the other values can be taken as 0, which is especially the case when the amount of 'k's are limited using pe. #k=1 as in:

("axial"-neighbor of )

(#j=n-1 can be left unspecified) j now runs through all the values in [0..k-1,k+1..n-1].

Further: without restrictions specified 'k' as well as 'i' run through all possible values, in combinations same letters assume same values. Thus makes it possible to specify a particular line within the hypercube (see r-agonal in pathfinder section)

Note: as far as I know this notation is not in general use yet(?), Hypercubes are not generally analyzed in this particular manner.

Further: "perm(0..n-1)" specifies a permutation of the n numbers 0..n-1.

Construction

Besides more specific constructions two more general construction method are noticeable:

KnightJump construction

This construction generalizes the movement of the chessboard horses (vectors ) to more general movements (vectors ). The method starts at the position P0 and further numbers are sequentially placed at positions further until (after m steps) a position is reached that is already occupied, a further vector is needed to find the next free position. Thus the method is specified by the n by n+1 matrix:

This positions the number 'k' at position:

C. Planck gives in his 1905 article "The theory of Path Nasiks" conditions to create with this method "Path Nasik" (or modern {perfect}) hypercubes.

Latin prescription construction

(modular equations). This method is also specified by an n by n+1 matrix. However this time it multiplies the n+1 vector [x0,..,xn-1,1], After this multiplication the result is taken modulus m to achieve the n (Latin) hypercubes:

LPk = ( l=0∑n-1 LPk,l xl + LPk,n ) % m

of radix m numbers (also called "digits"). On these LPk's "digit changing" (?i.e. Basic manipulation) are generally applied before these LPk's are combined into the hypercube:

nHm = k=0∑n-1 LPk mk

J.R.Hendricks often uses modular equation, conditions to make hypercubes of various quality can be found on http://www.magichypercubes.com/Encyclopedia at several places (especially p-section)

Both methods fill the hypercube with numbers, the knight-jump guarantees (given appropriate vectors) that every number is present. The Latin prescription only if the components are orthogonal (no two digits occupying the same position)

Multiplication

Amongst the various ways of compounding, the multiplication[1] can be considered as the most basic of these methods. The basic multiplication is given by:

nHm1 * nHm2 : n[ki]m1m2 = n[ [[ki \ m2]m1m1n]m2 + [ki % m2]m2]m1m2

Most compounding methods can be viewed as variations of the above, As most qualifiers are invariant under multiplication one can for example place any aspectial variant of nHm2 in the above equation, besides that on the result one can apply a manipulation to improve quality. Thus one can specify pe the J. R. Hendricks / M. Trenklar doubling. These things go beyond the scope of this article.

Aspects

A hypercube knows n! 2n Aspectial variants, which are obtained by coordinate reflection ([ki] --> [k(-i)]) and coordinate permutations ([ki] --> [perm[k]i]) effectively giving the Aspectial variant:

nHm~R perm(0..n-1); R = k=0∑n-1 ((reflect(k)) ? 2k : 0) ; perm(0..n-1) a permutation of 0..n-1

Where reflect(k) true iff coordinate k is being reflected, only then 2k is added to R. As is easy to see, only n coordinates can be reflected explaining 2n, the n! permutation of n coordinates explains the other factor to the total amount of "Aspectial variants"!

Aspectial variants are generally seen as being equal. Thus any hypercube can be represented shown in "normal position" by:

[k0] = min([kθ ; θ ε {-1,0}]) (by reflection) [k1 ; #k=1] < [k+11 ; #k=1] ; k = 0..n-2 (by coordinate permutation)

(explicitly stated here: [k0] the minimum of all corner points. The axial neighbour sequentially based on axial number)

Basic manipulations

Besides more specific manipulations, the following are of more general nature

- #[perm(0..n-1)] : component permutation

- ^[perm(0..n-1)] : coordinate permutation (n == 2: transpose)

- _2axis[perm(0..m-1)] : monagonal permutation (axis ε [0..n-1])

- =[perm(0..m-1)] : digit change

Note: '#', '^', '_' and '=' are essential part of the notation and used as manipulation selectors.

Component permutation

Defined as the exchange of components, thus varying the factor mk in mperm(k), because there are n component hypercubes the permutation is over these n components

Coordinate permutation

The exchange of coordinate [ki] into [perm(k)i], because of n coordinates a permutation over these n directions is required.

The term transpose (usually denoted by t) is used with two dimensional matrices, in general though perhaps "coordinate permutation" might be preferable.

Monagonal permutation

Defined as the change of [ki] into [kperm(i)] alongside the given "axial"-direction. Equal permutation along various axes can be combined by adding the factors 2axis. Thus defining all kinds of r-agonal permutations for any r. Easy to see that all possibilities are given by the corresponding permutation of m numbers.

Noted be that reflection is the special case:

~R = _R[n-1,..,0]

Further when all the axes undergo the same ;permutation (R = 2n-1) an n-agonal permutation is achieved, In this special case the 'R' is usually omitted so:

_[perm(0..n-1)] = _(2n-1)[perm(0..n-1)]

Digitchanging

Usually being applied at component level and can be seen as given by [ki] in perm([ki]) since a component is filled with radix m digits, a permutation over m numbers is an appropriate manner to denote these.

Pathfinders

J. R. Hendricks called the directions within a hypercubes "pathfinders", these directions are simplest denoted in a ternary number system as:

Pfp where: p = k=0∑n-1 (ki + 1) 3k <==> <ki> ; i ε {-1,0,1}

This gives 3n directions. since every direction is traversed both ways one can limit to the upper half [(3n-1)/2,..,3n-1)] of the full range.

With these pathfinders any line to be summed over (or r-agonal) can be specified:

[ j0 kp lq ; #j=1 #k=r-1 ; k > j ] < j1 kθ l0 ; θ ε {-1,1} > ; p,q ε [0,..,m-1]

which specifies all (broken) r-agonals, p and q ranges could be omitted from this description. The main (unbroken) r-agonals are thus given by the slight modification of the above:

[ j0 k0 l-1 sp ; #j=1 #k+#l=r-1 ; k,l > j ] < j1 k1 l-1 s0 >

Qualifications

A hypercube nHm with numbers in the analytical numberrange [0..mn-1] has the magic sum:

nSm = m (mn - 1) / 2.

Besides more specific qualifications the following are the most important, "summing" of course stands for "summing correctly to the magic sum"

- {r-agonal} : all main (unbroken) r-agonals are summing.

- {pan r-agonal} : all (unbroken and broken) r-agonals are summing.

- {magic} : {1-agonal n-agonal}

- {perfect} : {pan r-agonal; r = 1..n}

Note: This series doesn't start with 0 since a nill-agonal doesn't exist, the numbers correspond with the usual name-calling: 1-agonal = monagonal, 2-agonal = diagonal, 3-agonal = triagonal etc.. Aside from this the number correspond to the amount of "-1" and "1" in the corresponding pathfinder.

In case the hypercube also sum when all the numbers are raised to the power p one gets p-multimagic hypercubes. The above qualifiers are simply prepended onto the p-multimagic qualifier. This defines qualifications as {r-agonal 2-magic}. Here also "2-" is usually replaced by "bi", "3-" by "tri" etc. ("1-magic" would be "monomagic" but "mono" is usually omitted). The sum for p-Multimagic hypercubes can be found by using Faulhaber's formula and divide it by mn-1.

Also "magic" (i.e. {1-agonal n-agonal}) is usually assumed, the Trump/Boyer {diagonal} cube is technically seen {1-agonal 2-agonal 3-agonal}.

Nasik magic hypercube gives arguments for using {nasik} as synonymous to {perfect}. The strange generalization of square 'perfect' to using it synonymous to {diagonal} in cubes is however also resolve by putting curly brackets around qualifiers, so {perfect} means {pan r-agonal; r = 1..n} (as mentioned above).

some minor qualifications are:

- {ncompact} : {all order 2 subhyper cubes sum to 2n nSm / m}

- {ncomplete} : {all pairs halve an n-agonal apart sum equal (to (mn - 1)}

{ncompact} might be put in notation as : (k)∑ [ji + k1] = 2n nSm / m.

{ncomplete} can simply be written as: [ji] + [ji + k(m/2) ; #k=n ] = mn - 1.

Where:

(k)∑ is symbolic for summing all possible k's, there are 2n possibilities for k1.

[ji + k1] expresses [ji] and all its r-agonal neighbors.

for {complete} the complement of [ji] is at position [ji + k(m/2) ; #k=n ].

for squares: {2compact 2complete} is the "modern/alternative qualification" of what Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw called most-perfect magic square, {ncompact ncomplete} is the qualifier for the feature in more than 2 dimensions

Caution: some people seems to equate {compact} with {2compact} instead of {ncompact}. Since this introductory article is not the place to discuss these kind of issues I put in the dimensional pre-superscript n to both these qualifiers (which are defined as shown)

consequences of {ncompact} is that several figures also sum since they can be formed by adding/subtracting order 2 sub-hyper cubes. Issues like these go beyond this articles scope.

See also

References

- this is a n-dimensional version of (pe.): Alan Adler magic square multiplication

Further reading

- J.R.Hendricks: Magic Squares to Tesseract by Computer, Self-published, 1998, 0-9684700-0-9

- Planck, C., M.A.,M.R.C.S., The Theory of Paths Nasik, 1905, printed for private circulation. Introductory letter to the paper

External links

- The Magic Encyclopedia Articles by Aale de Winkel

- Magic Cubes and Hypercubes - References Collected by Marian Trenkler

- An algorithm for making magic cubes by Marian Trenkler

- multimagie.com Articles by Christian Boyer

- magichypercube.com A magic cube generator