Madonna Litta

The Madonna Litta is a late 15th-century painting, traditionally attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg. It depicts the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the Christ child, a devotional subject known as the Madonna lactans. The figures are set in a dark interior with two arched openings, as in Leonardo's earlier Madonna of the Carnation, and a mountainous landscape in aerial perspective can be seen beyond. In his left hand Christ holds a goldfinch, which is symbolic of his future Passion.

| Madonna Litta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Disputed attribution to Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1490 |

| Type | Tempera on canvas (transferred from panel) |

| Dimensions | 42 cm × 33 cm (17 in × 13 in) |

| Location | Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg |

Scholarly opinion is divided on the work's attribution, with some believing it to be the work of a pupil of Leonardo such as Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio or Marco d'Oggiono; the Hermitage Museum, however, considers the painting to be an autograph work by Leonardo. The painting takes its name from the House of Litta, a Milanese noble family in whose collection it was for much of the nineteenth century.

History

The Madonna Litta might be one of the paintings of the Madonna and Child recorded in Leonardo's studio before or during his first Milanese period (c.1481–3 to 1499). On a drawing in the Uffizi Leonardo noted that he had begun “two Virgin Maries” in late 1478 and an inventory of his studio written in 1482 (part of the Codex Atlanticus) again mentions two paintings of “Our Lady”. The second of these is, according to different interpretations, either noted as being “almost finished, in profile” or “finished, almost in profile”.[1] The Virgin's head in the Madonna Litta could be described either way, and it has therefore been argued that the painting was begun in Leonardo's first Florentine period and left unfinished until it was later worked up by a pupil in Milan.[2] Scientific analysis of the painting has, however, suggested that it was produced by only one artist.[3]

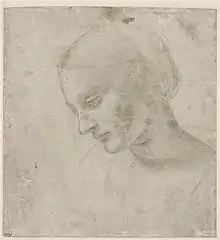

Several drawings have been identified as preparatory to the Madonna Litta. One, which is universally attributed to Leonardo, is a metalpoint drawing of a young woman's face in near profile, part of the Codex Vallardi in the Louvre. There is evidence that this sheet was used as an exemplum for teaching pupils in Leonardo’s workshop; on the reverse another artist has traced the outline of the face in pen and ink, a technique Leonardo himself used when developing compositions.[5] Further evidence of pupils copying the drawing comes in the form of a direct copy, by a rather uncertain draughtsman, on a sheet which was turned over and reused for a different drawing by another sixteenth-century artist; this is now in the Städel in Frankfurt.[6]

Two other drawings, in metalpoint with white lead highlights on blue prepared paper, are attributed to a follower of Leonardo, usually considered to be Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. One, a study for the Christ child's head, is in the Fondation Custodia in Paris; the other, in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, is a drapery study for the Virgin's garments. These have been attributed to Boltraffio on the basis of the Berlin drawing's similarity to other drapery studies by the artist.[7] It has been argued that the Paris and Berlin drawings are preparatory studies for the Madonna Litta rather than copies after it, as the drapery study shows more of the Virgin's right arm than the finished work, in which this is obscured by Christ's head. This suggests that the composition was partly pieced together from these studies.

A further related drawing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, attributed to Boltraffio, is of the Virgin's face in strict profile and does not resemble the finished painting in the Hermitage.[8] It has been argued that this study might represent an earlier idea by a pupil for the composition of the Madonna Litta, which the master Leonardo then 'corrected' with the drawing in the Louvre.[9]

The painting was repainted by an artist other than Leonardo in Milan around 1495.[4]

Provenance

It has been speculated that Leonardo might have taken the Madonna Litta with him to Venice in March 1500, as the diarist Marcantonio Michiel apparently recorded its presence in the Ca' Contarini in that city in 1543:

There is a little picture, of a foot or a little more, of an Our Lady, half length, who gives milk to the little boy, coloured by the hand of Leonardo da Vinci, a work of great power and highly finished.[10][lower-alpha 1]

The earliest print of the composition is Venetian, by an artist in the circle of Zoan Andrea, and at least one painted copy by the Venetian school is known, in the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona.

In 1784, the earliest secure date in its provenance, the painting was bought by Prince Alberico XII di Belgioioso from one Giuseppe Ro. After Belgioioso's death in 1813 it passed into the collection of the Litta family, from whom it takes its current name. In 1865 the Russian Tsar Alexander II acquired the panel from Count Antonio Litta,[12] quondam minister to Saint Petersburg, for the Hermitage Museum, where it has been exhibited to this day. Upon acquiring the painting the Hermitage had it transferred from wood to canvas, when it was again repainted.[4]

Attribution

That the painting was regarded in Leonardo's lifetime as his work is suggested by the large number of copies made of it. A popular candidate for authorship is Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. David Alan Brown argues that Marco d'Oggiono was responsible for the Madonna Litta as its composition is reflected in his later works, whereas it is not in those of Boltraffio.[13] In the major exhibition on Leonardo's first Milanese period held at the National Gallery in London in 2011–12 the painting was attributed to Leonardo, but art historian Martin Kemp has remarked that this was "presumably a condition of the loan".[14] Kemp said in 2017 that he regarded the painting as a Boltraffio.[15]

References

Footnotes

- A foot in Venetian measurements was 34.7cm, closer to the width of the Madonna Litta than its height.[11]

Citations

- Kemp 2001, pp. 263 and 293, n. 640

- Kemp 2006, pp. 32–3

- Syson et al. 2011, p. 222

- Wallace, Robert (1966). The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 153, 185.

- Syson et al. 2011, pp. 228–9

- Syson et al. 2011, pp. 230–1 (cat. no. 60)

- Syson et al. 2011, p. 234

- "Head of a Woman in Profile to Lower Left". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- Brown 2003, p. 26

- Quoted in Syson et al. 2011, p. 224

- Syson et al. 2011, p. 224

- Syson et al. 2011, p. 224, n. 5

- Brown 2003, p. 27

- Kemp, Martin (1 February 2012). "The National Gallery's blockbuster exhibition could mark a turning point for Leonardo scholars". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- "» Robert Simon Artwatch". artwatch.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

Sources

- Brown, David Alan (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: Art and Devotion in the Madonnas of his Pupils. Biblioteca d'arte. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana Editoriale.

- Fiorio, Maria Teresa (2000). Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio: Un pittore milanese nel lume di Leonardo. Milano: Jandi Sapi Editori. pp. 81–3. (cat. no. A3)

- Kemp, Martin, ed. (2001). Leonardo on Painting: An anthology of writings by Leonardo da Vinci with a selection of documents relating to his career as an artist. Nota Bene. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Kemp, Martin (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Syson, Luke; Keith, Larry; Galansino, Arturo; Mazzotta, Antonio; Nethersole, Scott; Rumberg, Per (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. London: National Gallery.

External links

Media related to Madonna Litta at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Madonna Litta at Wikimedia Commons