M11 link road protest

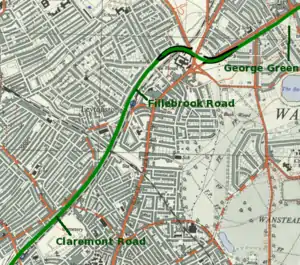

The M11 link road protest was a major anti-road protest in east London, England, in the early to mid-1990s opposing the construction of the "A12 Hackney to M11 link road", also known as the M11 Link Road. The link road was part of a significant local road scheme to connect traffic from the East Cross Route (A12) in Hackney Wick to the M11 via Leyton, Leytonstone, Wanstead and the Redbridge Roundabout, avoiding urban streets.

The road had been proposed since the 1960s, as part of the London Ringways, and was an important link between central London and the Docklands to East Anglia. However, road protests elsewhere had become increasingly visible, and urban road building had fallen out of favour with the public. A local Member of Parliament Harry Cohen, representing Leyton, had been a vocal opponent of this scheme.

The protests reached a new level of visibility during 1993 as part of a grassroots campaign where protesters came from outside the area to support local opposition to the road. The initial focus was on the removal of a tree on George Green, east of Wanstead, that attracted the attention of local, then national media. The activity peaked in 1994 with several high-profile protesters setting up micronations on property scheduled for demolition, most notably on Claremont Road in Leyton. The final stage of the protest was a single building on Fillebrook Road in Leytonstone, which, due to a security blunder, became occupied by squatters.

The road was eventually built as planned, and opened to traffic in 1999, but the increased costs involved in management and policing of protesters raised the profile of such campaigns in the United Kingdom, and contributed to several road schemes being cancelled or reviewed later on in the decade. Those involved in the protest moved on to oppose other schemes in the country, while opinions of the road as built have since been mixed. By 2014, the road had become the ninth most congested in the entire country.[1]

Background

The origin of the link road stems from what were two major arterial roads out of London (the A11 to Newmarket and Norwich, and the A12 to Colchester, Ipswich and Great Yarmouth) and subsequent improvements. The first of these was the Eastern Avenue improvement, that opened on 9 June 1924,[2] which provided a bypass of the old road through Ilford and Romford.

Proposals for the route first arose in the 1960s as part of the London Ringways plan, which would have seen four concentric circular motorways built in the city, together with radial routes, with the M11 motorway ending on Ringway 1, the innermost Ringway, at Hackney Marsh.[3]

A section of Ringway 1 known as the East Cross Route was built to motorway standards in the late 1960s and early 1970s and designated as the A102(M). A section of the M11 connecting Ringway 2 (now part of the North Circular Road) and Eastern Avenue to Harlow was completed in the late 1970s,[4] opening to traffic in 1977.[5]

The Ringways scheme met considerable opposition; there were protests when the Westway, an urban motorway elevated over the streets of Paddington, was opened in 1970, with local MP John Wheeler later describing the road's presence within 15 metres of properties as "completely unacceptable environmentally,"[6] and the Archway Road public inquiry was repeatedly abandoned during the 1970s as a result of protests.[7][8] By 1974, the Greater London Council announced it would not be completing Ringway 1.[9] The first Link Road Action Group to resist the M11 link road was formed in 1976,[10] and for the next fifteen years activists fought government plans through a series of public inquiries. Their alternative was to build a road tunnel, leaving the houses untouched, but this was rejected on grounds of cost.[11] Drivers travelling in the areas where the new roads would have been built had to continue using long stretches of urban single-carriageway roads. In particular, the suburbs of Leyton, Leytonstone and Wanstead suffered serious traffic congestion.[12][13]

The Roads for Prosperity white paper published in 1989 detailed a major expansion of the road building programme and included plans for the M12 Motorway between London and Chelmsford, as well as many other road schemes.[14] Although Harry Cohen, MP for Leyton suggested in May 1989 that the government should scrap the scheme,[15] a public enquiry was held for the scheme in November.[16]

The protest campaign in East London

Petition submitted to the House of Commons, June 1990[17]

By the 1980s, planning blight had affected the area and many of the houses had become home to a community of artists and squatters.[18] Eventually, contractors were appointed to carry out the work and a compulsory purchase of property along the proposed route was undertaken.[11] In March 1993, in preparation for the construction of the road, the Earl of Caithness, then the Minister of State for Transport, estimated that there would be 263 properties scheduled for demolition, displacing 550 people, of which he estimated 172 were seeking rehousing.[19] Several original residents, who had in some cases lived in their homes all their lives, refused to sell or move out of their properties.[20]

Protesters from the local area against the link road scheme were joined by large numbers of anti-road campaigners from around the UK and beyond, attracted by the availability of free housing along the route. These experienced protesters, who had participated in earlier events such as the Anti-Nazi League riots in Welling,[21] gave impetus to the campaign. The new arrivals used the skills they had developed during prior protests to construct "defences", blocking the original entrances to the houses and creating new routes directly between them.[11]

Sophisticated techniques were used to delay the construction of the road. Sit-ins and site invasions were combined with sabotage to stop construction work temporarily. This led to large numbers of police and constant security patrols being employed to protect the construction sites, at great expense. By December 1994, the total cost of construction had been estimated at £6 million and rising by £500,000 every month.[22]

The protesters were successful in publicising the campaign, with most UK newspapers and TV news programmes covering the protests on a regular basis. Desktop publishing, then in its infancy, was used to produce publicity materials for the campaign[23] and send out faxes to the media.[24] When the government began evicting residents along the route and demolishing the empty houses, the protesters set up so-called "autonomous republics" such as "Wanstonia" in some groups of the houses.[25][26] Extreme methods were used to force the engineers to halt demolition, including tunnels with protesters secured within by concrete.[27]

The chestnut tree on George Green

Until late 1993, local opposition to the M11 extension had been relatively limited. While opposition had been going for nearly ten years, institutional avenues of protest had been exhausted, and local residents were largely resigned to the road being built.[29] When outside protesters arrived in September 1993, few residents saw their mission as "their campaign".[30]

One section of the M11 extension was due to tunnel under George Green in Wanstead. Residents had believed that this would save their green, and a 250-year-old sweet chestnut tree that grew upon it,[31] but because this was a cut and cover tunnel, this required the tree to be cut down.[31]

Support for the protests started to extend to the local community when Jean Gosling, a lollipop lady in Wanstead, upon learning of the tree's impending destruction, rallied the support of local children (and was later fired from her job for doing so while wearing her uniform),[26][32] who in turn recruited their parents into the protests.[33] It was then that the non-resident radicals realised that they had significant local support.[31] When local residents gathered for a tree dressing ceremony on 6 November, they found their way barred by security fencing. With support from the protesters, they pulled it down.[31][25]

Protesters continued to delay the destruction of the tree. Solicitors for the campaign had even argued in court that receipt of a letter addressed to the tree itself gave it the status of a legal dwelling, causing a further delay.[31][34] In the early morning of 7 December 1993, several hundred police arrived to evict the protesters,[lower-alpha 1] which took ten hours to carry out.[lower-alpha 2] Protesters made numerous complaints against the police;[36] police, in turn, denied these allegations, attributing any misbehaviour to the protesters.[lower-alpha 3] Media attention started to increase regarding the protest, with several daily newspapers putting pictures of the tree on their front pages.[31]

Harry Cohen, MP for Leyton, started to become critical of the scheme and its progress. In March 1994, he said "the Department of Transport's pig-headed approach to the M11 link road has been a shambles, and a costly one at that," and described the ongoing police presence as "a miniature equivalent of the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait."[26] According to him, local resident Hugh Jones had been threatened by demolition men wielding sledgehammers and pickaxes, adding "the project has cost £500,000 in police time alone, to take over and demolish a 250-year-old chestnut tree and half a dozen houses".[26]

Claremont Road

By 1994, properties scheduled for demolition had been compulsory purchased, and most were made uninhabitable by removing kitchens, bathrooms and staircases. The notable exception was in one small street, Claremont Road, which ran immediately next to the Central line and consequently required every property on it to be demolished.[27] The street was almost completely occupied by protesters except for one original resident who had not taken up the Department for Transport's offer to move, 92-year-old Dolly Watson, who was born in number 32 and had lived there nearly all her life.[37][38][39] She became friends with the anti-road protesters, saying "they're not dirty hippy squatters, they're the grandchildren I never had."[39] The protesters named a watchtower, built from scaffold poles, after her.[40]

A vibrant and harmonious community sprung up on the road, which even won the begrudging respect of the authorities.[41] The houses were painted with extravagant designs, both internally and externally, and sculptures erected in the road;[27][42][43] the road became an artistic spectacle that one said "had to be seen to be believed".[44]

In November 1994, the eviction of Claremont Road took place, bringing an end to the M11 link road resistance as a major physical protest. Bailiffs, accompanied by the police in full riot gear, carried out the eviction over several days, and the Central line, running adjacent to the road, was suspended. As soon as eviction was completed, the remaining properties were demolished.[27] In the end, the cost to the taxpayer was over a million pounds in police costs alone.[45] Quoting David Maclean, "I understand from the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis that the cost of policing the protest in order to allow bailiffs to take possession of the premises in Claremont road was £1,014,060." Cohen complained in Parliament about police brutality, stating "were not many of my constituents bullied—including vulnerable people, and others whose only crime was living on the line of route?"[22] The then Secretary of State for Transport, Brian Mawhinney, pointed out that there had already been three public inquiries at which protesters could have lodged their objections against the line of the route.[22]

Towards the end

Following the Claremont Road eviction, non-resident protesters moved on to other sites such as Newbury. Meanwhile, Fillebrook Road near Leytonstone Underground station had already had several houses demolished on it due to problems with vandalism.[46] By 1995, the only house left standing was number 135.[47] The house was originally scheduled for demolition at the same time as the others, but had been left standing in order to give the tenant additional time to relocate. After they had done so, on 11 April 1995, the Department for Transport removed the water supply and part of the roof, and left two security guards on duty. When the guards decided to sleep overnight in their cars that evening, leaving the house unoccupied, the protesters moved in.[48] The house was renamed Munstonia (after The Munsters, thanks to its spooky appearance). Like "Wanstonia", they proclaimed themselves a micro-nation and designed their own national anthem and flag, though author Joe Moran mentions their legitimacy was complicated by the protesters continuing to claim unemployment benefits from the "mother country."[49]

A tower was built out of the remains of the roof, similar to one that had existed at Claremont Road, and a system of defences and blockades were built. A core of around 30 protesters ensured that there were always people staying there (a legal requirement for a squatted home, as well as a defence against eviction).[48] They were finally evicted on 21 June 1995, whereupon, as at Claremont Road, the building was immediately demolished. The total cost of removing the protesters from Munstonia was given to be £239,349.52, not including additional costs of security guards.[47]

Construction of the road, already underway by this stage, was then free to continue largely unhindered, although systematic sabotage of building sites by local people continued. It was completed in 1999 and given the designation A12; its continuation, the former A102(M), was also given this number as far as the Blackwall Tunnel.

The official opening of the road in October 1999 took place without fanfare, being opened by the Highways Agency Chief Executive rather than a politician, with only journalists with passes being admitted to the ceremony.[50]

Consequences of the protest campaign

The M11 link road protest was ultimately unsuccessful in its aim to stop the building of the link road. The total cost of compensation for the project was estimated to be around £15 million.[51]

Proposals for the M12 motorway were cancelled in 1994 during the first review of the trunk road programme.[52] The most significant response from the government occurred when Labour came into office following the 1997 general election, with the announcement of the New Deal for Trunk Roads in England. This proposal cancelled many previous road schemes, including the construction of the M65 over the Pennines, increased fuel prices, and ensured that road projects would only be undertaken when genuinely necessary,[53] stating "there will be no presumption in favour of new road building as an answer."[54]

Some protesters went on to join the direct action campaign Reclaim the Streets.[55][56][57] A protester arrested and detained on the grounds of breach of the peace unsuccessfully challenged the UK Government's legislation at the European Court of Justice.[58]

In 2002, in response to a major new road building programme and expansion of aviation,[59] a delegation of road protest veterans visited the Department for Transport to warn of renewed direct action in response, delivering a D-lock as a symbol of the past protests.[60] One such protestor, Rebecca Lush went on to found Road Block to support road protesters and challenge the government. In 2007, Road Block became a project within the Campaign for Better Transport.[61] The M11 Link road protests inspired the launch of the video activism organisation Undercurrents. Training activists to film the protests, they released You've got to be choking in 1994, a 40-minute documentary about the M11 link road campaign.[62]

In 2007, the BBC reported that the cost of the M11 link road had doubled due to the intervention of protesters.[63] Residents in Leytonstone have complained that, following the completion of the road, their streets became rat runs for commuters trying to get ahead of queues.[64]

See also

- Environmental direct action in the United Kingdom

- Road protest in the United Kingdom

- Newbury Bypass

- Twyford Down

- 491 Gallery – a squatted social centre in Leytonstone in a building that escaped demolition

Notes

- The BBC give the figure as two hundred;[35] Wall gives the figure as four hundred.[31]

- According to the BBC;[35] Wall gives a figure of nine hours.[31]

- The BBC quotes then-Chief Superintendent Stuart Giblin as saying "My officers acted professionally despite some of the comments and behaviour of the protesters."[35]

References

- ITV News 2014.

- Gosling, in Hansard & 23 July 1924.

- Moran 2009, p. 202.

- "The Motorway Archive". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- Horam, in Hansard & 15 December 1976.

- Wheeler, in Hansard & 22 May 1981.

- Hansard & 28 April 1978.

- Hansard & 11 May 1984.

- Hansard & 12 November 1974.

- Moran 2009, p. 214.

- 20th Century London 2005.

- Fraser, in Hansard & 28 July 1965.

- Sorensen, in Hansard & 8 May 1963.

- DfT 1989.

- Cohen and Channon, in Hansard & 18 May 1989.

- Hansard & 29 November 1989.

- Hansard & 18 June 1990.

- Cohen, in Hansard & 7 June 1985.

- Sinclair, in Hansard & 16 March 1993.

- Cohen and Chope, in Hansard & 17 May 1991.

- Cohen and Norris, in Hansard & 25 February 1994.

- Cohen and Mawhinney, in Hansard & 19 December 1994.

- Boyle 1994.

- "kriptick" 2004.

- Moran 2009, p. 215.

- Cohen, in Hansard & 11 March 1994.

- Measure 2006.

- McKay 1996, p. 149 "A chestnut tree (later capitalized and given a definite article) suddenly became the focus for protesters and increasing numbers of locals ... The protection of the Chestnut Tree came quickly to symbolize what was under threat from the road[.]"

- Doherty 2002, p. 200.

- Doherty 2002, p. 201.

- Wall 1999, p. 76.

- McKay 1996, p. 150.

- Wall 1999, p. 75.

- McKay 1996, p. 149.

- BBC News 1993.

- Rowell 1996 "The police were accused of widespread brutality in evicting the protesters. Forty-nine complaints against police were recorded by protesters[.]" Note that Drury & Reicher 2000 gives a figure of fifty-seven.

- Shepard, Hayduk and Rofes 2002, p. 217. "In place of the usual petitions and marches to save the street, protesters simply moved in—occupying every house on the block (save one house owned and occupied by a feisty 92-year-old woman, who refused the Department of Transport's order to move)."

- Duncombe 2002, p. 349.

- Geffen 2003.

- Duncombe 2002, p. 351.

- Bordern, Kerr and Rendell 2001, p. 231.

- McKay 1996, p. 151.

- Bordern, Kerr and Rendell 2001, p. 229.

- SchNEWS 1994, p. 1.

- Hansard & 9 December 1994.

- Hansard & 20 December 1991.

- Cohen and Norris, in Hansard & 5 July 1995.

- The Independent 1995.

- Moran 2009, p. 217.

- "A12 – M11 Link Road Official Opening 6 October". Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- Cohen and Hill, in Hansard & 27 July 2000.

- Hansard & 30 March 1994.

- Marshall 2001.

- Department for Transport 1998.

- Duncombe 2002, p. 352.

- Shepard, Hayduk and Rofes 2002, p. 218. "This coalition, armed with the action model pioneered on Claremont Road, fueled the rebirth of Reclaim the Streets."

- Moran 2009, p. 221.

- European Court of Justice 1998.

- New Statesman 2003.

- Indymedia 2004.

- The Guardian 2008.

- Undercurrents 2017.

- BBC 2006. "Figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act show that the campaign against the M11 extension contributed to a 100% increase in costs."

- Hackney Council 2004.

Citations

Books

- Bordern, Iain; Kerr, Joe; Rendell, Jane (2001). The Unknown City: Contesting Architecture and Social Space. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-52335-3.

- Roads for Prosperity. Department for Transport. 1989.

- Doherty, Brian (2002). Ideas and Actions in the Green Movement. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17401-5.

- Duncombe, Stephen (2002). Cultural Resistance Reader. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-379-4.

- McKay, George (1996). Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-908-3.

- Moran, Joe (2009). On Roads : A Hidden History. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84668-052-6.

- Rowell, Andrew (1996). Green Backlash: Global Subversion of the Environment Movement. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12827-7.

- Shepard, Benjamin; Hayduk, Ronald; Rofes, Eric (2002). From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization. Verso. p. 218. ISBN 1-85984-356-5.

- Wall, Derek (1999). Earth First! and the Anti-Roads Movement: Radical Environmentalism and Comparative Social Movements. Routledge.

News articles

- "Anti-road protests 'boosted cost'". BBC News. 15 April 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- "Activists lose battle over chestnut tree". BBC News: ON THIS DAY. 7 December 1993. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "Direct action road protest veterans delegation to Dept for Transport". indymedia. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "M11 Latest News" (PDF). SchNEWS. 7 December 1994. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- "Our House". The Independent. 20 May 1995. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- "Rebecca Lush Blum – Profile". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- "Do we have to set England alight again?". New Statesman. 30 June 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- "Britain's ten most congested roads are all in London". ITV News. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

Websites

- "M11 Protest". 20th Century London. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Marshall, Chris (2001). "British Roads FAQ". Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Boyle, Sebastian (1994). "Claremont Road E11 / A festival of resistance -newspaper". Museum of London. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Geffen, Roger (2003). "Claremont Road – At This Juncture". SchNEWS. Archived from the original on 8 May 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- "CASE OF STEEL AND OTHERS v. THE UNITED KINGDOM" (PDF). Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. 23 September 1998. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- "Summary of Rat Running around Well Street Common (Homerton Neighbourhood meeting minutes)" (Microsoft Word document). 8 December 2004. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- "kriptick" (2004). "Tenth anniversary of Operation Roadblock against the M11 link road". UK Indymedia. Retrieved 15 June 2007. Tells of the "skipped 286 computers running Windows 3.1", and the "creaky" computers pounding out press releases and leaflets.

- Measure, Maureen (2006). "Claremont Road and the M11 Link Road". Leyton & Leytonstone Historical Society. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- "New Deal for Trunk Roads" (PDF). Department for Transport. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "My first film- from 1993 is not "advertiser-friendly"". Undercurrents. 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

Hansard

- Harry Gosling (23 July 1924). "Wanstead - Southend Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Reginald Sorensen (8 May 1963). "Major Road Reconstruction, Leyton". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Tom Fraser (28 July 1965). "Traffic Congestion (Leytonstone and Stratford)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "M23 (LONDON)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Archive. 12 November 1974. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- John Horam (15 December 1976). "M11 (opening)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Archway Road, London (Public Inquiry)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. 28 April 1978. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- John Wheeler (22 May 1981). "Heavy Lorries (London)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Archway Road, North London (Inquiry)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. 11 May 1984. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen (7 June 1985). "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen and Paul Channon (18 May 1989). "Roads (White Paper)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Debates. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Archive. 29 November 1989. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Archive. 18 June 1990. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen and Christopher Chope (17 May 1991). "24 Claremont Road, E11". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "127–129 Fillebrook Road, Leytonstone". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Archive. 20 December 1991. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Malcolm Sinclair, 20th Earl of Caithness (16 March 1993). "M.11 Link: Effects on Housing". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen and Steven Norris (25 February 1994). "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- Harry Cohen (11 March 1994). "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Trunk Roads (Review)". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- "Written Answers to Questions Friday 9 December 1994". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. 9 December 1994. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Archive. 19 December 1994. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen and Steven Norris (5 July 1995). "Road Protestors". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Harry Cohen and Keith Hill (27 July 2000). "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

Further reading

- Andy Letcher, The Scouring of the Shire: Fairies, Trolls and Pixies in Eco-Protest Culture (2001)

- Aufheben, The Politics of Anti-Road Struggle and the Struggles of Anti-Road Politics: The Case of the No M11 Link Road Campaign. In DIY Culture, ed. George McKay. 100–28. London: Verso, 1998.

- "M11 Link Road". Hansard of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. 6 March 2002. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Butler, Beverley (November 1996). "The Tree, the Tower and the Shaman: The Material Culture of Resistance of the No M11 Link Roads Protest of Wanstead and Leytonstone, London". Journal of Material Culture. 1 (3): 337–363. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

External links

- Maps of east London showing the location of the M11 link road, now called Eastway (A12)

- Harry Cohen's commons speech protesting against the construction of the road and police response to protesters

- Leytonstone pre the M11 (A12) - A set of photographs of the area covered by the link road, before it was built, including houses before occupation by protesters.

- Pro-campaign page on the 10th Anniversary of the end of the protest (Indymedia)

- Part 2 of the above article, covering "Operation Roadblock"

- The Politics of Anti-road Struggle and the Struggles of Anti-Road politics – The Case of the No M11 link Road Campaign

- The destruction of Claremont Road, Wanstead

- LINKED, a radio art project by Graeme Miller on the site of the link road about the demolished houses and streets

- Kinokast video of Claremont Road eviction, 1994

- You've Got to be Choking Too - 9-minute documentary film of the anti-road campaign

- Life in the Fast Lane: The No M11 Story - Feature-length documentary about the campaign.