Lung nodule

A lung nodule or pulmonary nodule is a relatively small focal density in the lung. A solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) or coin lesion,[1] is a mass in the lung smaller than 3 centimeters in diameter. There may also be multiple nodules.

| Lung nodule | |

|---|---|

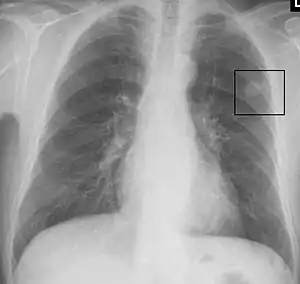

| |

| Chest X-ray showing a solitary pulmonary nodule (indicated by a black box) in the left upper lobe. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

One or more lung nodules can be an incidental finding found in up to 0.2% of chest X-rays[2] and around 1% of CT scans.[3]

The nodule most commonly represents a benign tumor such as a granuloma or hamartoma, but in around 20% of cases it represents a malignant cancer,[3] especially in older adults and smokers. Conversely, 10 to 20% of patients with lung cancer are diagnosed in this way.[3] If the patient has a history of smoking or the nodule is growing, the possibility of cancer may need to be excluded through further radiological studies and interventions, possibly including surgical resection. The prognosis depends on the underlying condition.

Causes

Not every round spot on a radiological image is a solitary pulmonary nodule: it may be confused with the projection of a structure of the chest wall or skin, such as a nipple, a healing rib fracture or electrocardiographic monitoring.

The most important cause to exclude is any form of lung cancer,[4] including rare forms such as primary pulmonary lymphoma, carcinoid tumor and a solitary metastasis to the lung (common unrecognised primary tumor sites are melanomas, sarcomas or testicular cancer). Benign tumors in the lung include hamartomas and chondromas.

The most common benign coin lesion is a granuloma (inflammatory nodule), for example due to tuberculosis or a fungal infection, such as Coccidioidomycosis.[5] Other infectious causes include a lung abscess, pneumonia (including pneumocystis pneumonia) or rarely nocardial infection or worm infection (such as dirofilariasis or dog heartworm infestation). Lung nodules can also occur in immune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or organizing pneumonia.

A solitary lung nodule can be found to be an arteriovenous malformation, a hematoma or an infarction zone. It may also be caused by bronchial atresia, sequestration, an inhaled foreign body or pleural plaque.

Risk factors

Risk factors for incidentally discovered nodules are mainly:

- General risk factors of lung cancer such as exposure to tobacco smoking or other carcinogens such as asbestos and previously diagnosed cancer, respiratory infections, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[6]

- Size: larger size confers a higher risk of cancer[7]

- Location: Upper lobe location is a risk factor for cancer, while a location close to a fissure or the pleura indicates a benign lymph node,[7] especially if having a triangular shape.[8]

- Margin morphology: a spiculated margin is a risk factor for cancer.[7] Benign causes tend to have a well defined border, whereas lobulated lesions or those with an irregular margin extending into the neighbouring tissue tend to be malignant.[9] In particular, spiculations are highly predictive of malignancy with a positive predictive value up to 90%.[8] Also, a "notch sign", which is an abrupt indentation of the nodule, increases the risk of cancer, but may also be found in granulomatous diseases.[8]

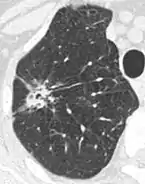

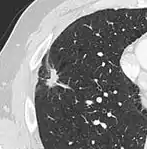

Round well-delineated solid lung nodule with smooth border.[8]

Round well-delineated solid lung nodule with smooth border.[8] Lobulated nodule.[8]

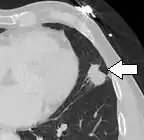

Lobulated nodule.[8] Spiculated lung nodule.[8]

Spiculated lung nodule.[8] A "notch sign".[8]

A "notch sign".[8] A triangular perifissural node can be diagnosed as a benign lymph node.[8]

A triangular perifissural node can be diagnosed as a benign lymph node.[8]

- Multiplicity: Where the presence of up to an additional 3 nodules has been found to increase the risk of cancer, but decrease in case of 4 or more additional ones, likely because it indicates a previous granulomatous infection rather than cancer.[7]

- Growth rate: solid cancers generally doubles in volume over between 100 and 400 days, while subsolid cancers (generally representing adenocarcinomas) generally doubles in volume over 3 to 5 years.[7] One volume doubling equals approximately a 26% increase in diameter.[7]

- Presence of emphysema and/or fibrosis is a risk factor for cancer.[7] In comparison, the typical size doubling are less than 20 days for infections, and more than 400 days for benign nodules.[10]

- Enhancement: If the exam is done as a combined non-contrast and contrast CT, a solitary nodule with an enhancement off less than 15 Hounsfield units (HU), whereas a higher enhancement indicates a malignant tumor (with a sensitivity estimated at 98%).[11]

- Areas of fatty tissue (−40 to −120 HU) indicates a hamartoma. However, only about 50% of hamartomas are fat containing.[8]

- If there is a central cavity, then a thin wall points to a benign cause whereas a thick wall is associated with malignancy (especially 4 mm or less versus 16 mm or more).[9]

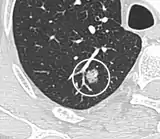

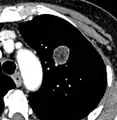

Low attenuating nodule (in this case a fat containing hamartoma).[8]

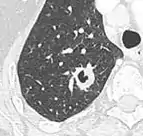

Low attenuating nodule (in this case a fat containing hamartoma).[8] Cavitation with relatively thick wall, in this case aspergilloma).[8]

Cavitation with relatively thick wall, in this case aspergilloma).[8]

- In case of calcifications, a popcorn-like appearance indicates a hamartoma, which is benign.[2]

- In case of subsolid nodules, being part solid has a higher risk of cancer than being purely ground glass opacity.

Part solid nodule.[8]

Part solid nodule.[8] Ground glass opacity nodule.[8]

Ground glass opacity nodule.[8]

- Pleural retraction is far more common in cancers.[8] It is the pulling of visceral pleura towards the nodule.[8]

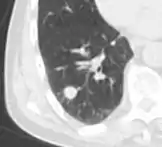

Nodule with pleural retraction.[8]

Nodule with pleural retraction.[8] In this case, pleural retraction is seen as a triangular fat component.[8]

In this case, pleural retraction is seen as a triangular fat component.[8]

- A lung nodule abutting a pulmonary cyst is a rare finding, yet indicating cancer.[8]

- Bubble-like lucencies in the nodule indicate cancer:[8]

.png.webp)

- Vascular convergence is where vessels converge to a nodule without adjoining or contacting the edge of the nodule, and is mainly seen in peripheral subsolid lung cancers.[8] It reflects angiogenesis.[8]

Air bronchograms is defined as a pattern of air-filled bronchi on a background of airless lung, and may be seen in both benign and malignant nodules, but certain patterns thereof may help in risk stratification.[8]

CT densitometry, measuring absolute attenuation on the Hounsfield scale, has low sensitivity and specificity and is not routinely employed, apart from helping to distinguish solid from ground glass lesions, and to confirm visible fatty areas or calcifications.[11]

Diagnosis

A diagnostic workup can include a variety of scans and biopsies.

Definition

Nodular density is used to distinguish larger lung tumors, smaller infiltrates or masses with other accompanying characteristics. An often used formal radiological definition is the following: a single lesion in the lung completely surrounded by functional lung tissue with a diameter less than 3 cm and without associated pneumonia, atelectasis (lung collapse) or lymphadenopathies (swollen lymph nodes).[12][9]

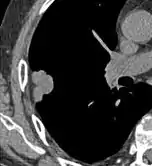

CT scan

For incidentally detected nodules on CT scan, Fleischner Society guidelines are given in table below. For multiple nodes, management is based on the most suspicious node.[7] These guidelines do not apply in lung cancer screening, in patients with immunosuppression, or in patients with known primary cancer.[7]

| <6 mm (<100mm3) | 6-8mm (100-250mm3) | >8mm (>250mm3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single nodule | Low risk | No routine follow-up | CT after 6–12 months, then consider CT after 18–24 months | Consider CT at 3 months, PET-CT or biopsy |

| High risk | Optionally, CT after 12 months | CT after 6–12 months, then after 18–24 months | ||

| Multiple nodules | Low risk | No routine follow-up | CT after 3–6 months, then consider CT after 18–24 months | |

| High risk | Optionally CT after 12 months | CT after 3–6 months, then after 18–24 months | ||

| Total size <6 mm (<100mm3) | Total size >6mm (>1003) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single nodule | Ground glass opacity | No routine follow-up | CT after 6–12 months to check if persistent, then after 2 years and then another 2 years |

| Part solid | No routine follow-up | CT after 6–12 months:

|

|

| Multiple nodules |

CT after 3–6 months. If stable, consider CT after 2 and then another 2 years. | CT after 3–6 months, then after 18–24 months | |

More frequent CT scans than what is recommended has not been shown to improve outcomes but will increase radiation exposure and the unnecessary health care can be expected to make the patient anxious and uncertain.[13]

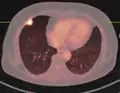

PET scan

If there is an intermediate risk of malignancy, further imaging with positron emission tomography (PET scan) is appropriate (if available). It can be done simultaneously as a CT scan in the form of PET-CT. Around 95% of patients with a malignant nodule will have an abnormal PET scan, while around 78% of patients with a benign nodule will look normal on PET (this is the test sensitivity and specificity).[14] Thus, an abnormal PET scan will reliably pick up cancer, but several other types of nodules (inflammatory or infectious, for example) will also show up on a PET scan. If the nodule has a diameter of less than one centimeter, PET scans are often avoided because of an increased risk of falsely normal results.[14][15][16] Cancerous lesions usually have a high metabolism on PET, as demonstrated by their high uptake of FDG (a radioactive sugar).

PET-CT of a tuberculoma.

PET-CT of a tuberculoma.

Other imaging

Other potential forms of medical imaging of pulmonary nodules include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).[17]

Histopathology

For cases suspicious enough to proceed to biopsy, small biopsies can be obtained by core needle or bronchoscopy are commonly used for diagnosis of lung nodules.[18] CT guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsies have also proven to be very helpful in the diagnosis of SPN.[5]

In selected cases, nodules can also be sampled through the airways using bronchoscopy or through the chest wall using fine-needle aspiration (which can be done under CT guidance). Needle aspiration can only retrieve groups of cells for cytology and not a tissue cylinder or biopsy, precluding evaluation of the tissue architecture. Theoretically, this makes the diagnosis of benign conditions more difficult, although rates higher than 90% have been reported.[19] Complications of the latter technique include hemorrhage into the lung and air leak in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall (pneumothorax). However, not all these cases of pneumothorax need treatment with a chest tube.[20]

Excision

Where workup indicates a high risk of cancer, excision can be performed by thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, which can also confirm the diagnosis by microscopical examination.

Footnotes

- "Coin lesion (Lung)".

- Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH; Fein; Feinsilver (June 2003). "Clinical practice. The solitary pulmonary nodule". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (25): 2535–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp012290. PMID 12815140.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Alzahouri K, Velten M, Arveux P, Woronoff-Lemsi MC, Jolly D, Guillemin F; Velten; Arveux; Woronoff-Lemsi; Jolly; Guillemin (2008). "Management of SPN in France. Pathways for definitive diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodule: a multicentre study in 18 French districts". BMC Cancer. 8: 93. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-8-93. PMC 2373300. PMID 18402653.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thiessen, N. R.; Bremner, R. (2010). "The solitary pulmonary nodule: Approach for a general surgeon". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 90 (5): 1003–18. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2010.07.002. PMID 20955880.

- Jude, Cecilia M.; Nayak, Nita B.; Patel, Maitraya K.; Deshmukh, Monica; Batra, Poonam (2014). "Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis: Pictorial Review of Chest Radiographic and CT Findings". RadioGraphics. 34 (4): 912–925. doi:10.1148/rg.344130134. PMID 25019431.

- Zhan, Ping; Xie, Haiyan; Xu, Chunhua; Hao, Keke; Hou, Zhibo; Song, Yong (2013). "Management strategy of solitary pulmonary nodules". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 5 (6): 824–829. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.13. PMC 3886686. PMID 24409361.

- MacMahon, Heber; Naidich, David P.; Goo, Jin Mo; Lee, Kyung Soo; Leung, Ann N. C.; Mayo, John R.; Mehta, Atul C.; Ohno, Yoshiharu; Powell, Charles A.; Prokop, Mathias; Rubin, Geoffrey D.; Schaefer-Prokop, Cornelia M.; Travis, William D.; Van Schil, Paul E.; Bankier, Alexander A. (2017). "Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images: From the Fleischner Society 2017". Radiology. 284 (1): 228–243. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161659. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 28240562.

- Snoeckx, Annemie; Reyntiens, Pieter; Desbuquoit, Damien; Spinhoven, Maarten J.; Van Schil, Paul E.; van Meerbeeck, Jan P.; Parizel, Paul M. (2017). "Evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule: size matters, but do not ignore the power of morphology". Insights into Imaging. 9 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1007/s13244-017-0581-2. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC 5825309. PMID 29143191.

- Winer-Muram HT (April 2006). "The solitary pulmonary nodule". Radiology. 239 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1148/radiol.2391050343. PMID 16567482.

- Truong, MD, Mylene T.; Ko, MD, Jane P.; Rossi, MD, Santiago E.; Rossi, MD, Ignacio; Viswanathan, MD, Chitra; Bruzzi, MBBCh, John F.; Marom, MD, Edith M.; Erasmus, MD, Jeremy J. (2014). "Update in the Evaluation of the Solitary Pulmonary Nodule". Radiographics. 34 (6): 1658–1679. doi:10.1148/rg.346130092. PMID 25310422.

- Tanay Patel (2019-02-25). "Lung Metastases Imaging". Medscape. Updated: Sep 30, 2018

- Tan BB, Flaherty KR, Kazerooni EA, Iannettoni MD; Flaherty; Kazerooni; Iannettoni; American College of Chest Physicians (January 2003). "The solitary pulmonary nodule". Chest. 123 (1 Suppl): 89S–96S. doi:10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.89S. PMID 12527568. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society (September 2013). "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society. Retrieved 6 January 2013., which cites

- Smith-Bindman, R; Lipson, J; Marcus, R; Kim, KP; Mahesh, M; Gould, R; Berrington de González, A; Miglioretti, DL (Dec 14, 2009). "Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer". Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (22): 2078–86. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. PMC 4635397. PMID 20008690.

- Wiener, RS; Gould, MK; Woloshin, S; Schwartz, LM; Clark, JA (Mar 2013). "What do you mean, a spot?: A qualitative analysis of patients' reactions to discussions with their physicians about pulmonary nodules". Chest. 143 (3): 672–7. doi:10.1378/chest.12-1095. PMC 3590883. PMID 22814873.

- Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, Owens DK; MacLean; Kuschner; Rydzak; Owens (February 2001). "Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 285 (7): 914–24. doi:10.1001/jama.285.7.914. PMID 11180735.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Khan A (March 2007). "ACR Appropriateness Criteria on solitary pulmonary nodule". J Am Coll Radiol. 4 (3): 152–5. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2006.12.003. PMID 17412254.

- Vansteenkiste JF, Stroobants SS; Stroobants (January 2006). "PET scan in lung cancer: current recommendations and innovation". J Thorac Oncol. 1 (1): 71–3. doi:10.1097/01243894-200601000-00014. PMID 17409830.

- Cronin P, Dwamena BA, Kelly AM, Carlos RC; Dwamena; Kelly; Carlos (2008). "Solitary pulmonary nodules: meta-analytic comparison of cross-sectional imaging modalities for diagnosis of malignancy". Radiology. 246 (3): 772–82. doi:10.1148/radiol.2463062148. PMID 18235105.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mukhopadhyay, S (2012). "Utility of small biopsies for diagnosis of lung nodules: Doing more with less". Modern Pathology. 25 Suppl 1: S43-57. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2011.153. PMID 22214970.

- Klein JS, Salomon G, Stewart EA; Salomon; Stewart (March 1996). "Transthoracic needle biopsy with a coaxially placed 20-gauge automated cutting needle: results in 122 patients". Radiology. 198 (3): 715–20. doi:10.1148/radiology.198.3.8628859. PMID 8628859.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Connolly JE; McAdams; Connolly (2000). "Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part II. Evaluation of the indeterminate nodule". Radiographics. 20 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja0259. PMID 10682771.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |