Los Angeles Street

Los Angeles Street, originally known as Calle de los Negros or Alley of the Black People, is a major thoroughfare in Downtown Los Angeles, California, dating back to the origins of the city as the Pueblo de Los Ángeles.

Location

The principal length of the street proceeds north from 23rd Street, past Interstate 10, through the Fashion District, past the western edge of Little Tokyo, past the Caltrans District Headquarters, the former Los Angeles Police Department Headquarters at Parker Center and the Los Angeles Mall (which contains City Hall East).

Los Angeles Street ends at Alameda Street, north of the US 101 near Olvera Street and Union Station.

In South Los Angeles there are two other portions of Los Angeles Street, one running from Slauson Avenue to 59th Place and another from 122nd Street to 124th Street near Willowbrook.

History

The block of Los Angeles Street that runs by the Old Plaza was originally known as "Calle de los Negros" or "Alley of the Black People". On late 19th century maps it is also marked with a contemporary English translation of that phrase, Nigger Alley.[1] The Chinese massacre of 1871 took place on Los Angeles Street when it was still known as Calle de los Negros. The printing house for the city's first newspaper, Star of Los Angeles, was located on Los Angeles Street, which was known at the time as Calle Zanja Madre (Mother Ditch street).[2]

Los Angeles Street was the easternmost street in the city's central business district during the 1880s and 1890s. Around Los Angeles and 3rd was the wholesale district, which over time moved further and further southeast into what is now the Fashion District and beyond.

Education

Landmarks from Plaza to 3rd Street

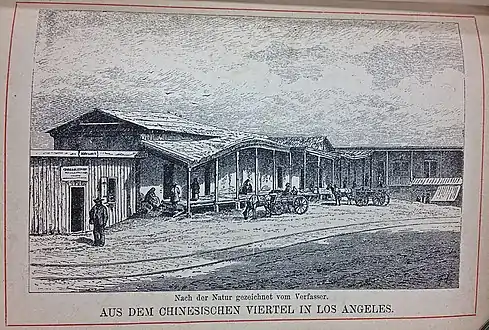

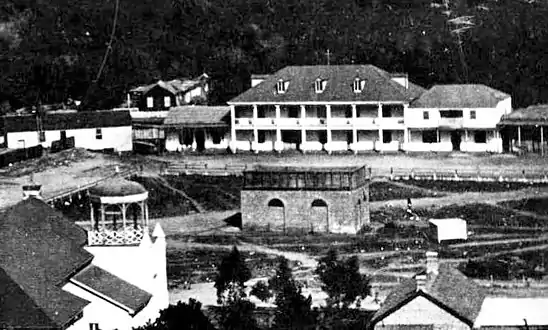

Old Chinatown stretched from Sanchez Street across Los Angeles Street to what is now Union Station. c.1885.

Old Chinatown stretched from Sanchez Street across Los Angeles Street to what is now Union Station. c.1885.

Lugo Adobe lining the eastern edge of Los Angeles Plaza. The street in front of the adobe was part of Los Angeles St. starting in the 1880s.  Chinese American Museum in the Garnier Building

Chinese American Museum in the Garnier Building

1882 view, looking north from Broad Place along Calle de los Negros to the Ignacio Del Valle adobe in the far background. At left, with the peeling paint, is the Coronel Adobe (SE corner of Arcadia). A few years later, both adobes would be demolished and Los Angeles St. would be extended northward to (and past) the Plaza.  Looking east on Arcadia towards houses lining the east side of Broad Place. Aliso Street runs form their right side towards the background. Calle de los Negros runs to the left in front of them. The Coronel Adobe is at left.

Looking east on Arcadia towards houses lining the east side of Broad Place. Aliso Street runs form their right side towards the background. Calle de los Negros runs to the left in front of them. The Coronel Adobe is at left.

Adobes in Calle de los Negros %252C_Calle_de_los_Negros_(r).png.webp)

Broad Place at north end of Los Angeles Street c.1870s. At back, Coronel Adobe (l), Calle de los Negros (r)

Northern end of Los Angeles Street

The Colonel Adobe was demolished in 1888 and 1896 Sanborn maps show that the Del Valle adobe had been removed, and Los Angeles Street had been extended[3] to form the eastern edge of the Plaza, thus passing in front of the Lugo Adobe. Calle de los Negros remained for a few more decades, behind a row of houses lining the east side of Los Angeles Street between Arcadia and Aliso streets. This was also the western edge of Old Chinatown from around the 1880s through 1930s. It reached eastward across Alameda St. to cover most of the area that is now Union Station. It proceeded one more block past the Plaza, with the buildings on the east side of Olvera Street forming its western edge, until terminating at Alameda Street.[4]

Eastern edge of Plaza

Since the early 1950s, Los Angeles Street has formed the eastern edge of the Plaza, but the buildings lining its eastern edge, including the Lugo Adobe, were removed.[5][6] The site is now Father Serra Park.

From the Plaza north to Alameda

When it was extended past the Plaza in 1888,[3] Los Angeles Street terminated one short block north of the Plaza at Alameda Street. Now, Los Angeles Street turns east at the north side of the Plaza to terminate at Alameda Street at a right angle, directly across from the Union Station complex. What was the short block of Los Angeles Street north of the Plaza is now part of Placita Dolores, a small open plaza which surrounds a statue of Mexican charro entertainer Antonio Aguilar on horseback.[7]

Calle de los Negros

Until the late 19th century, Los Angeles Street did not form the east side of the Plaza; it ran south only from Broad Place at the intersection of Arcadia Street. Here, the Coronel Adobe blocked the path north one block to the Plaza, but just slightly to the right (east) of the path of Los Angeles Street was Calle de los Negros (Spanish-language name; marked on post-1847 maps as Negro Alley or Nigger Alley), a narrow, one-block north–south street likely named after darker-skinned Mexican afromestizo and/or mulatto residents during the Spanish colonial era.[8][9]. At the north end of Calle de los Negros stood the Del Valle adobe (also known as the Matthias or Matteo Sabichi house),[10][11] at the southern edge of which one could turn left and enter the plaza at its southeast corner. Calle de los Negros was famous for its saloons and violence in the early days of the town, and by the 1880s was considered part of Chinatown, lined with Chinese and Chinese American residences, businesses and gambling dens.[12][13]

The neglected dirt alley was already associated with vice by the early 1850s, when a bordello and its owner both known as La Prietita (the dark-skinned lady) were active here. Its other businesses included malodorous livery stables, a pawn shop, a saloon, a theater and a connected restaurant. Historian James Miller Guinn wrote in 1896, "in the flush days of gold mining, from 1850 to 1856, it was the wickedest street on earth...In length it did not exceed 500 feet, but in wickedness, it was unlimited. On either side it was lined with saloons, gambling hells, dance houses and disreputable dives. It was a cosmopolitan street. Representatives of different races and many nations frequented it. Here the ignoble red man, crazed with aguardiente, fought his battles, the swarthy Sonorian plied his stealthy dagger, and the click of the revolver mingled with the clink of gold at the gaming table when some chivalric American felt that his word of “honah” had been impugned."[8]

By 1871, the alley was notorious as a "racially, spatially, and morally disorderly place", according to historian César López. It was here that a growing number of Chinese immigrant railroad laborers settled after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. There, William Estrada notes, the "Chinese of Los Angeles came to fill an important sector of the economy as entrepreneurs. Some became proprietors and employees of small hand laundries and restaurants; some were farmers and wholesale produce peddlers; others ran gambling establishments; and some occupied other areas left vacant by the absence of workers in the gold rush migration to California." The Chinese population increased from 14 in 1860 to almost 200 by 1870. Guinn stated that the alley stayed "wicked" through and after its transition to the city's Old Chinatown.[8]

Calle de los Negros was reconfigured in 1888 when Los Angeles Street was extended north, with a small, shallow row of houses remaining between the new section of Los Angeles street's eastern edge and the western edge of the new, shortened alley.[3][14] The site of Calle de los Negros is now the Pueblo parking lot and a cloverleaf-style entrance to the US 101 freeway.

Coronel Adobe

The Coronel Adobe was built in 1840 by Ygnacio Coronel as a family home. It stood at the northwest corner of Arcadia Street and Calle de los Negros; Los Angeles Street terminated at its southern end. The area gradually became an area for gambling and saloons, and upper-class families left to live elsewhere. Around 1849, they sold the house to a "sporting fraternity", which operated a popular 24-hour gambling establishment with games including monte, faro, and poker; up to $200,000 in gold could be seen on the tables at a time. Arguments ensued and murders were frequent. The building later became a dance hall where "lewd women" were employed, aimed at the Mexican-American population. After that, still in the 1850s, it became a grocery and dry goods store (Corbett & Barker), then a storage house for iron and hard lumber for Harris Newmark Co. It was then leased to a Chinese immigrant. In 1871, it was the site of the Chinese massacre of 1871. The Adobe was torn down in 1888 in order to extend Los Angeles Street north past the Plaza.[3]

Garnier Building

At 419 N. Los Angeles Street, at the northwest corner of Arcadia, is the Garnier Building, built in 1890, part of the city's original Chinatown. The southern portion of the building was demolished in the 1950s to make way for the Hollywood Freeway. The Chinese American Museum is now located in the Garnier Building. It should not be confused with another Garnier Block/Building on Main St. a block away now commonly known as Plaza House.

%252C_218-224_(now_318-324)_N._Los_Angeles_St._c.1890s.png.webp) Haas, Baruch & Co., successor to Hellman, Haas & Co., SE corner of Aliso St. c.1890s

Haas, Baruch & Co., successor to Hellman, Haas & Co., SE corner of Aliso St. c.1890s.jpg.webp)

1885 view of the east side of Los Angeles St. with Bell Block at center with its two story porch, to its right Mellus Row, then Hellman, Haas & Co. At center is Aliso St. heading east (top center of photo).

West side of Los Angeles street from Arcadia to Commercial, 1890s. Hellman Block at left, Arcadia Block at right

Arcadia Block, 1870s. SW corner of Los Angeles and Arcadia streets. .jpg.webp) Los Angeles St. north from 1st St. ca. 1910

Los Angeles St. north from 1st St. ca. 1910.jpg.webp) Los Angeles St. north from 3rd St. ca. 1910

Los Angeles St. north from 3rd St. ca. 1910

Los Angeles Street was lined with mostly commercial buildings; the southeast end of the business district around Los Angeles and 3rd streets was the Wholesale District. Only a few buildings were notable:

West side south of Arcadia

- Arcadia Block: southwest corner of Arcadia Street. Built 1858, razed in 1927.[15]

- Hellman Block: in 1870, banker and University of Southern California founder Isaias W. Hellman erected the Hellman Block at the northwest corner of Los Angeles and Commercial streets.[16] This is one of several Hellman Blocks or Hellman Buildings in the city.

East side south of Aliso

- Bell Block was at the southeast corner of Aliso Street. It was General John C. Fremont's headquarters and the first Los Angeles City Hall. Captain Alexander Bell and Mellus lived here (Francis Mellus married a niece of Mrs. Bell's). It was taken over by General Fremont for his headquarters and thus became the state capital for the short period of his acting as governor. The Los Angeles City organization was formed in this building in 1850.[17]

- Mellus Row, adjacent to Bell Block on the south

- Hellman, Haas & Co. grocers (a partnership of Abraham Haas and Herman W. Hellman), the predecessors of Smart & Final. Located in the 1880s and 1890s at 218-224 (pre-1890 numbering, post-1890 numbering: 318-324) N. Los Angeles St., adjacent to Mellus Row on the south.[18] Not to be confused with the Haas Building.

- Between Aliso and Temple streets on the east side of Los Angeles St. at #300 is the Federal Building, opened in 1965-6, architect Welton Becket.[19] Temple was extended east of Main Street between Aliso Street and a street that was known as both Requena and Market street. Adjacent and to its east is the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building and United States Courthouse, completed in 1992.

- Between Temple and First streets is Parker Center, the Los Angeles Police Department headquarters from 1955–2009

- At the southeast corner of First Street, Little Tokyo begins. At this corner was the Tomio Department Store, and two more Japanese-American department stores, the Asia Company and Hori Brothers were located east of it on 1st Street during the 1920s.[20] Now the site of Weller Court and the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Los Angeles Downtown, formerly the New Otani Hotel.

Landmarks in Historic Core: 3rd Street to Olympic

King Edward Hotel (built 1906, NW corner of 5th St.)

King Edward Hotel (built 1906, NW corner of 5th St.) Baltimore Hotel (built 1910, SW corner of 5th St.)

Baltimore Hotel (built 1910, SW corner of 5th St.)

Corner of 5th St.

- Baltimore Hotel, opened 1910, architect Arthur Rowland Kelley[21]

- King Edward Hotel, opened 1906, architects Parkinson and Bergstrom[22]

Corner of 9th St.

- Cooper Building, northeast corner, opened 1926, architects Curlett & Beelman.[23] By the early 1980s the Cooper Building was already a key destination for retail shoppers looking for fashion bargains in the Los Angeles Fashion District.[24]

- Gerry Building, southeast corner, opened 1947, Streamline Moderne architectural style

External links

References

- "Los Angeles Massacre Site", National Park Service

- Guinn, James Miller (1915). A History of California and an Extended History of Los Angeles and Environs: Also Containing Biographies of Well Known Citizens of the Past and Present (Public domain ed.). Historic Record Company. pp. 407–.

- "An Historic Building: Torn Down to Make Way for a Street: Reminiscences of the Past: History of the Movement to Open Los Angeles Street to Alameda". Los Angeles Herald. January 13, 1888.

- Sanborn map of Los Angeles, 1894, plate 12, right half, lower right

- "End of an Era". Los Angeles Times. February 7, 1951. p. 31.

END OF AN ERA This is the old Lugo House on Los Angeles St., facing the Plaza, mainstay of 19 buildings which will be torn down, beginning today, to clear the area between Union Station and the Plaza. Some say the Lugo House was begun in 1811. Once it was a magnificent dwelling, later it became the center of the pueblo's social life and now, after -years of disrepair, it will die despite efforts of historical societies to save it.

- "Wreckers Go to Lugo House and 18 Other Ancient Abodes". Los Angeles Times. February 7, 1951. p. 31.

- Zavis, Alexandra (September 17, 2012). "Los Angeles unveils statue of Mexican singer-actor Antonio Aguilar". Los Angeles Times.

- Lopez, Cesar. "Lost in Translation: From Calle de los Negros to Nigger Alley to North Los Angeles Street to Place Erasure, Los Angeles 1855–1951" (PDF). Southern California Quarterly. 94 (1 (Spring 2012)): 39–40.

- Beherec, Marc (2019). "John Romani's Forgotten 1984 Excavations at CA-LAN-007 and the Archeology of Native American Los Angeles" (PDF). SCA Proceedings. 33: 155. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Los Angeles' Little Italy, p.12

- Marc A. Beherec (AECOM), "John Romani's Forgotten 1984 Excavations at CA-LAN-007 and the Archaeology of Native American Los Angeles", Society for California Archaeology, pp.155 ff.

- vol. 1, Sheet 12_a, Sanborn 1888 map of Los Angeles (City), via Los Angeles Public Library

- "Los Angeles…1850" (map), UCLA map collection via Online Archive of California

- Sanborn 1894 map of Los Angeles, vol. 1, sheet 14b

- "Historic Building Is Razed: Flood of Memories Released". Los Angeles Times. May 15, 1927.

- “Hellman Block”, Calisphere

- File:Los Angeles Street and Aliso Street from Baker Block looking east, downtown Los Angeles, 1885 (CHS-1859).jpg, Wikimedia Commons

- "Abraham Haas: Pioneer Jewish Purveyor of Food Stuffs, Wholesale & Retail, Los Angeles", Jewish Museum of the American West

- "Built by Becket" via Los Angeles Conservancy

- Lemmon, Ben (May 13, 1929). "The Corners of Los Angeles: First and Los Angeles". Los Angeles Times. p. 22.

- https://esotouric.com/2018/08/24/baltimorehotel/

- "King Edward Hotel", Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1906, p. 70

- https://www.emporis.com/buildings/206589/cooper-building-los-angeles-ca-usa

- Yoshihara, Nancy (March 7, 1982). "Garment District Goes Boom". Los Angeles Times.