List of ironclad warships of Italy

Starting in 1860, the Royal Sardinian Navy began ordering ironclad warships for what would shortly become the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) following the unification of Italy the next year. The first of these vessels, the two vessels of the Formidabile class, were small broadside ironclads ordered from France and built to French designs. These were followed by the three Principe di Carignano-class ironclad, all of which were built in Italy; these were originally unarmored ships that were converted while under construction. Further orders abroad followed, with the two American-built Re d'Italia-class ironclads, the four French-built Regina Maria Pia-class ironclads, and the British-built ram Affondatore all being laid down between 1861 and 1863. Four more vessels in the first generation of Italian ironclads were laid down in Italy between 1863 and 1865, two each of the Roma and Principe Amedeo classes.

Most of these ships were constructed at the beginning of the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race and nearly all of them, with the exception of one of the Italian-built ships, had entered service in time for the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866, and they saw action at the Battle of Lissa in July 1866. There, the Italian fleet was defeated by the smaller Austrian Navy and Re d'Italia was sunk. This led to a period of neglect for the Regia Marina, as naval budgets were reduced and new construction stopped. By the early 1870s, the Italian government began a new program of construction to counter what was now the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which had built several ironclads after Lissa. The naval minister Benedetto Brin was responsible for most of the vessels built as part of this program, beginning with the large and powerful Caio Duilio class, two ships that carried four massive 100-ton guns. These were followed with the two Italia-class ironclads, which dispensed with the heavy side armor of earlier designs in favor of very high speed; this has led to them being described as "proto-battlecruisers." As a reaction to these very large ships while Brin was out of power, the navy acquired the three smaller Ruggiero di Lauria-class ironclads. The last of the second generation of ironclads, the Re Umberto class, were again designed by Brin.

The second generation of Italian ironclads had uneventful careers, spending much of their time occupied with training exercises. Despite Italy's rivalry with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy signed the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882, redirecting Italian naval strategy against France. Thus, the exercises of the period simulated battles with the French navy. Some of the ships saw action during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, where they provided gunfire support to Italian forces in North Africa, and those still in service by the time Italy entered World War I in 1915 continued to serve as guard ships in Italian ports in the Adriatic Sea. Most of the ships that were still extant after the war were broken up in the 1920s, though Ruggiero di Lauria, which had been converted into a floating oil tank, was still in the inventory during World War II, and she was sunk by Allied bombers in 1943.

| Armament | The number and type of the primary armament |

|---|---|

| Armor | The maximum thickness of the belt armor (or deck armor, where applicable) |

| Displacement | Ship displacement at full combat load |

| Propulsion | Number of shafts, type of propulsion system, and top speed generated |

| Service | The dates work began and finished on the ship and its ultimate fate |

| Laid down | The date the keel assembly commenced |

| Commissioned | The date the ship was commissioned |

Formidabile class

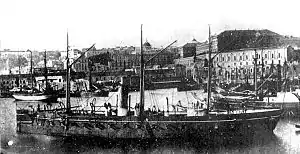

The first Italian ironclads, the two Formidabile-class ships, were actually ordered from a French shipyard by the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860, shortly before the unification of Italy under the Sardinian King Victor Emmanuel II. The two ships were initially conceived as armored floating batteries similar to the French Dévastation class that had proved so effective at the Battle of Kinburn in 1855. After work on the ships had begun, they were redesigned as sea-going broadside ironclads, which necessitated a reduction in their artillery battery by a third (from thirty to twenty guns). They formed the basis for an ironclad fleet aimed at defeating the Austrian Navy, since the Austrian Empire was the primary obstacle to the unification of all lands claimed by Italy.[1][2]

Both ships saw action against Austrian forces during the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866, including during the Lissa campaign, though neither ship participated in the Battle of Lissa itself. Formidabile had been too badly damaged during an attack on the main coastal fortifications on the island the day before the battle and had been forced to withdraw, while Terrible had been stationed to the south and her captain delayed rejoining the fleet until after the battle had ended.[3][4] Both were modernized in the 1870s, though they had become obsolete due to the rapid pace of naval developments during the period, being surpassed first by central battery ships and then by turret ships.[5] Formidabile and Terrible served as training ships from the mid-1880s until they were scrapped in 1903 and 1904, respectively.[6]

| Ship | Armament[6] | Armor[6] | Displacement[6] | Propulsion[6] | Service[6] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Formidabile | 4 × 203 mm (8 in) guns 16 × 164 mm (6 in) guns |

109 mm (4.3 in) | 2,807 long tons (2,852 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) | December 1860 | May 1862 | Broken up, 1903 |

| Terribile | June 1860 | September 1861 | Broken up, 1904 | ||||

Principe di Carignano class

.jpg.webp)

At the same time that Sardinia ordered the two Formidabile-class ships, the navy also awarded contracts for a pair of unarmored steam frigates, Principe di Carignano and Messina. Like the Formidabiles, these two ships were redesigned after they had been laid down to convert them into broadside ironclads. A third ship, Principe Umberto, was too far advanced in her construction to allow for conversion, and so she was completed as a wooden vessel. To replace Principe Umberto, the navy ordered another member of the class, Conte Verde, which was built to a modified design. The primary difference between the first two vessels and Conte Verde was the lack of a complete armored belt; she had armor protection just for the bow and stern. All three ships carried a battery of twenty-two 203 mm (8 in) and 164 mm (6.5 in) guns, though Principe di Carignano had ten of the former and twelve of the latter, while Messina and Conte Verde both had four and eighteen, respectively.[7][8]

Principe di Carignano was the only member of the class to have been completed in time for the Third Italian War of Independence. She took part in the Battle of Lissa, though she was the lead ship in the Italian line of battle, and was not heavily engaged in the action, since the Austrian commander, Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, had attacked the Italian fleet at its center.[9][10] Like the Formidabiles, the Principe di Carignano-class ships rapidly became obsolete in the 1870s,[5] and as a result saw limited activity for the remainder of their careers. In 1875, Principe di Carignano was sold for scrap, and the other two ships were stricken from the naval register five years later to reduce the Italian naval budget; Messina was sold for scrap, but Conte Verde remained extant until 1898, when she too was ultimately broken up.[11][12]

| Ship | Armament[11] | Armor[11] | Displacement[11] | Propulsion[11] | Service[11] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Principe di Carignano | 10 × 203 mm guns 12 × 164 mm guns |

121 mm (4.75 in) | 3,912 long tons (3,975 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 10.4 knots (19.3 km/h; 12.0 mph) | January 1861 | 11 June 1865 | Broken up, 1875 |

| Messina | 28 September 1861 | February 1867 | Broken up, 1880 | ||||

| Conte Verde | 2 March 1863 | December 1871 | Broken up, 1898 | ||||

Re d'Italia class

After the first orders had been placed with Italian shipyards, the newly-formed Kingdom of Italy began to place orders for additional ironclads abroad, since Italian firms did not have the capacity to accept the number of contracts required by the Italian navy. The first of these foreign-built ships, the Re d'Italia class, were ordered from the United States, from a design based heavily on the French ironclad Gloire. They were significantly more powerful than the earlier Italian ironclads, carrying a battery of thirty-six heavy guns on the broadside. The ships proved to be disappointments in service, in part due to their sterns, which were not protected and directly led to the loss of Re d'Italia at the Battle of Lissa. They were also poorly built; the American shipyard used unseasoned timbers to construct their hulls, and Re di Portogallo was discarded relatively early in her career after they were found to have severely rotted.[8][13]

Re d'Italia served as the flagship of the Italian fleet from her commissioning until shortly before the Battle of Lissa. The Italian fleet commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, transferred to the brand-new turret ship Affondatore moments before the Austrian fleet attacked, which created widespread confusion in the Italian fleet, which was largely not aware of the change. In the ensuing melee, Re d'Italia had her rudder shot away, and having been rendered unmaneuverable, was rammed and sunk by the Austrian flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max. Re di Portogallo was also rammed, but she was only lightly damaged.[14][15] Re di Portogallo saw little activity over the next decade, like the rest of the Italian ironclad fleet. In 1875, she was discarded owing to a combination of her badly rotted hull, and as a means reduce naval expenditures while the large and very expensive Caio Duilio-class ironclads were being built.[11][12]

| Ship | Armament[11] | Armor[11] | Displacement[11] | Propulsion[11] | Service[11] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Re d'Italia | 6 × 203 mm guns 30 × 164 mm guns |

114 mm (4.5 in) | 5,700 long tons (5,800 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) | 21 November 1861 | 14 September 1864 | Sunk, Battle of Lissa, 1866 |

| Re di Portogallo | December 1861 | 23 August 1864 | Broken up, 1875 | ||||

Regina Maria Pia class

.jpg.webp)

To continue its naval expansion program, the Regia Marina placed orders for four more ironclads from French shipyards in 1862. The design for the new ships was prepared by French naval constructors; since they were built by three different shipyards, they varied slightly in their dimensions, but they were broadly similar in all major respects. They carried most of their battery of twenty-six guns in the traditional broadside arrangement, with the exception of three of the 164 mm guns, which were placed in forward and rearward firing bunkers as chase guns. Though not as powerful in terms of gun power as the Re d'Italia class that preceded them, they nevertheless proved to be more effective in service, remaining in active service until the 1880s.[16][17]

All four ships were completed in time for the Third War of Italian independence, where they formed the core of the Italian ironclad fleet. Distributed along the Italian line, they were heavily engaged in the battle; San Martino attempted to rescue Re d'Italia before the latter was rammed and sunk, and in the confusion, she accidentally collided with Regina Maria Pia. Ancona also crashed into another Italian warship, the coastal defense ship Varese in the melee, but none of these vessels was badly damaged.[18] The four ships served with the fleet for the next two decades, including on tours in Italy's colonial empire.[19] All four ships were modernized in the late 1880s, and were thereafter used as training ships. Regina Maria Pia, Ancona, and San Martino were stricken from the naval register in 1903–1904, while Castelfidardo lingered on as a torpedo training ship until 1910, when she too was sold for scrapping.[20]

| Ship | Armament[20] | Armor[20] | Displacement[20] | Propulsion[20] | Service[20] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Regina Maria Pia | 8 × 203 mm guns 22 × 164 mm guns. |

121 mm | 4,527 long tons (4,600 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12.96 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) | 22 July 1862 | 17 April 1864 | Broken up, 1904 |

| San Martino | 9 November 1864 | Broken up, 1903 | |||||

| Castelfidardo | May 1864 | Broken up, 1910 | |||||

| Ancona | 11 August 1862 | April 1866 | Broken up, 1903 | ||||

Roma class

In 1863, the Regia Marina ordered another pair of ironclads;[20] by this time, foreign navies had begun to experiment with the first central battery ships, which discarded the usual broadside arrangement in favor of a shorter battery located amidships. This allowed designers to use a significantly shorter (and correspondingly much lighter) section of side armor to protect the guns, which in turn permitted the carrying of heavier, more powerful guns. And since the resulting ship could be shorter, it would also be more maneuverable. Additionally, central battery arrangements typically allowed for end-on fire from some of the guns.[21] Roma was completed to her original design, but Venezia was extensively reworked while still under construction to convert her into a central battery ship. Instead of the battery of five 254 mm and ten 203 mm guns carried in Roma, Venezia could employ a battery of eighteen 254 mm guns.[20][22] Ironically, by the time Venezia entered service, the Italian navy had begun building even more advanced vessels like the Caio Duilio-class turret ships that were laid down that year.[5]

Like most of the other first generation ironclads built in Italy, both vessels were completed too late to see service during the Third Italian War of Independence, and as a result of the Regia Marina's defeat in the war, saw little activity for the duration of their careers. Roma was mobilized during the Franco-Prussian War, during which Italy took advantage of the French defeat to seize Rome. Roma and the rest of the fleet was to attack the port of Civitavecchia, but the fleet was unable to assemble sufficient forces for the operation. In 1880, Venezia became a torpedo training ship, while Roma was converted into a depot ship in 1890. Venezia was sold for scrap in 1896; Roma was set on fire by lightning that year and proved to be a total loss, forcing her disposal as well.[23]

| Ship | Armament[20] | Armor[20] | Displacement[20] | Propulsion[20] | Service[20] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Roma | 5 × 10 in (254 mm) guns 12 × 203 mm guns |

150 mm (5.9 in) | 6,151 long tons (6,250 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) | February 1863 | May 1869 | Broken up, 1896 |

| Venezia | 1 April 1873 | ||||||

Affondatore

Affondatore was the last foreign-built ironclad of the Regia Marina; she was ordered from Britain in 1862. She was also the only armored ram to be built for Italy. The vessel's designer, then-Commander Simone Antonio Saint-Bon, originally intended the ship to be unarmed, using only her ram to attack other vessels, but another designer at the British shipbuilder altered the design to add a pair of 300-pound Armstrong guns in single gun turrets. Since she was intended to ram other warships, she was completed with a low freeboard and a minimal superstructure. The ship was still fitting out in June 1866, when Italy was preparing to declare war on Austria; the Regia Marina, eager to receive the powerful new ship, sent the crew to bring the ship, incomplete, back to Italy to strengthen the fleet.[24][25]

Affondatore joined the fleet while it was conducting its campaign against the island of Lissa, and on the morning of the battle, as the Austrian fleet approached, Persano shifted his flag from Re d'Italia to Affondatore without informing the rest of the fleet. He attempted to steam up and down the disengaged side of the Italian fleet to issue orders to individual ships, but their captains were unaware that Persano was aboard Affondatore, so they ignored him. After Re d'Italia had been rammed and sunk, Persano finally decided to commit Affondatore to the battle, and he half-heartedly and unsuccessfully attempted to ram the Austrian ship of the line Kaiser. After the two fleets disengaged, the Italians withdrew to Ancona, where Affondatore foundered either due to the damage received in the battle,[26] or the fact that her low freeboard did not permit her to weather a severe storm that struck the port.[27] She was refloated and repaired, and in the late 1880s, Affondatore was rebuilt into a more modern warship. She became a training ship in 1891, and remained in service until 1907, when she was stricken from the register and converted into a depot ship. Her ultimate fate is unknown.[20]

| Ship | Armament[20] | Armor[20] | Displacement[20] | Propulsion[20] | Service[20] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Affondatore | 2 × 300-pounder guns | 127 mm (5 in) | 4,307 long tons (4,376 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12 knots | 11 April 1863 | 20 June 1866 | Unknown, stricken, 1907 |

Principe Amedeo class

The two Principe Amedeo-class ships were the last of the first generation of Italian ironclads; they were also the only Italian-built ships designed as ironclads (as opposed to the converted wooden frigates of the Principe di Carignano class), and the only Italian vessels designed from the ground up as central battery ships. Principe Amedeo and Palestro positioned their guns differently; both mounted the 279 mm gun as bow chaser, but the six 254 mm guns aboard Principe Amedeo were located in a single, central casemate, while Palestro carried four of them in a casemate further aft and the other two in the same forward casemate as the bow chaser.[28]

The ships were completed too late to take part in the final stages of the wars of Italian unification. Instead, they were assigned to the Italian colonial empire, with occasional stints in the main Italian fleet.[29] In the late 1880s, Principe Amedeo and Palestro were withdrawn from frontline service and employed as headquarters ships for the harbor defense forces of Taranto and La Maddalena, respectively. Principe Amedeo was stricken from the naval register in 1895 and used as an ammunition depot ship in Taranto until 1910, when she was sold for scrap. Palestro was employed as a training ship between 1894 and 1900, when she too was stricken from the register. She was broken up between 1902 and 1904.[30]

| Ship | Armament[30] | Armor[30] | Displacement[30] | Propulsion[30] | Service[30] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Principe Amedeo | 6 × 254 mm guns 1 × 279 mm (11 in) gun |

221 mm (8.7 in) | 6,020 long tons (6,120 t) | One shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12.2 knots (22.6 km/h; 14.0 mph) | August 1865 | 15 December 1874 | Broken up, 1910 |

| Palestro | 11 July 1875 | Broken up, 1902 | |||||

Caio Duilio class

By the early 1870s, the Italian government decided to reinvest in the Regia Marina and rebuild its fleet, initially in an attempt to gain a significant advantage over the Austrian navy.[31] As the first step of this new program, the navy ordered a pair of large turret ships designed by Benedetto Brin. Brin revised the design several times during their construction, ultimately settling on an armament of four massive 100-ton guns in two twin-gun turrets, which were mounted amidships en echelon, allowing both to fire ahead, astern, and on a limited arc to either broadside. Brin also adopted a cellular "raft" design in the bow and stern, which was intended to reduce the risk of flooding due to battle damage; this would allow Brin to limit the length of the belt armor and thus keep displacement on the very large ships as low as possible.[32]

Shortly after the ships entered service, Italy signed the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, rendering moot the original strategic plan for the vessels. As a result, the primary potential opponent became France, Germany's traditional rival. Accordingly, the Italian fleet began to conduct war games throughout the 1880s and 1890s to develop doctrines for a future war with France.[33][34] Enrico Dandolo was extensively rebuilt in the mid-1890s and received more modern quick-firing guns, but the modernization proved to be too expensive to rebuild Caio Duilio as well. Long since obsolete, Caio Duilio and Enrico Dandolo were reduced to training ships in 1902 and 1905, respectively. Caio Duilio was converted into a depot ship in 1909, but her ultimate fate is unknown. Enrico Dandolo became a guard ship in 1913, and served in this capacity through World War I. She was stricken in 1920 and broken up that year.[30][35]

| Ship | Armament[30] | Armor[30] | Displacement[30] | Propulsion[30] | Service[30] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Caio Duilio | 4 × 450 mm (17.7 in) guns | 550 mm (21.5 in) | 12,071 long tons (12,265 t) | Two shafts, compound steam engines, 15.04 knots (27.85 km/h; 17.31 mph) | 24 April 1873 | 6 January 1880 | Unknown, converted to oil storage hulk, 1909 |

| Enrico Dandolo | 8 January 1873 | 11 April 1882 | Broken up, 1920 | ||||

Italia class

The Italian reconstruction program continued under Brin's direction with the construction of the two Italia-class ships in 1876–1887. These two ships were broadly similar to the Caio Duilio class, though they differed in several significant ways. First, they discarded the heavy side armored belt of the Caio Duilios and instead relied on a sloped armored deck backed by the cellular raft pioneered in the earlier vessels.[36] The reduced weight of the hull allowed the vessels to be significantly faster than any other ironclad in the world;[37] in fact, the combination of high speed, heavy guns, and light armor protection has led naval historians like Lawrence Sondhaus to refer to them as "proto battlecruisers".[5] In addition, the Italias used much lighter barbette mounts for their main battery, as opposed to the heavy and slow turrets of the Caio Duilios.[36]

The two Italia-class ironclads served in the fleet with the Caio Duilios for the majority of their active careers. Like the Caio Duilios, they were primarily occupied with training exercises during this period. In the early 1900s, the Regia Marina considered rebuilding the ships along the same lines as Enrico Dandolo, but it determined that the cost would have been prohibitively high. Instead, they were reduced to subsidiary roles, with Lepanto becoming a gunnery training ship in 1902 and Italia becoming a torpedo training ship in 1909.[36] Both ships were activated during the Italo-Turkish War in 1911, and they were sent to Tripoli to provide gunfire support to Italian forces that had captured the North African city.[38] Lepanto was sold for scrap in March 1915, shortly before Italy entered World War I, but Italia remained in service through the war, first as a guard ship in Brindisi. In December 1917, she was converted into a grain carrier and thereafter served with the Ministry of Transport and the State Railways, before being returned to the Regia Marina in 1921 and then being scrapped that year.[36][39]

| Ship | Armament[36] | Armor[36] | Displacement[36] | Propulsion[36] | Service[36] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Italia | 4 × 432 mm (17 in) guns | 102 mm (4 in) (deck) | 15,407 long tons (15,654 t) | Four shafts, compound steam engines, 17.8 knots (33.0 km/h; 20.5 mph) | 3 January 1876 | 16 October 1885 | Broken up, 1921 |

| Lepanto | 4 November 1876 | 16 August 1887 | Broken up, 1915 | ||||

Ruggiero di Lauria class

By 1880, Brin had been forced out as the Italian naval minister,[40] and his place had been taken by Admiral Ferdinando Acton; Acton opposed the very large battleships that Brin had designed (and especially the weakly-armored Italia class), and so he instructed the design staff to prepare a smaller vessel, limited to 10,000 long tons (10,000 t) displacement. He also mandated that the new ships should return to the defensive design philosophy of the Caio Duilio class. Several improvements were incorporated, however, including new breech-loading guns, compound armor in place of the wrought iron used in the earlier vessels.[41] Nevertheless, they were obsolescent by the time they entered service; by the late 1880s, the British Royal Navy had begun building the Royal Sovereign-class battleships, the first pre-dreadnought battleships, which rendered older ironclad battleships obsolescent. In addition, technological progress, particularly in armor production techniques—first Harvey armor and then Krupp armor—contributed to the ships' rapid obsolescence.[42]

Owing in part to their dated design, the three ships had uneventful careers, spending the 1890s in the main Italian fleet where they took part in maneuvers but saw no action. Having begun building a series of modern battleships, the Regia Marina discarded Ruggiero di Lauria and Francesco Morosini in 1909, the latter being used as a target ship in torpedo tests and the former becoming a floating oil tank. Ruggiero di Lauria was renamed GM 45, and was ultimately sunk by Allied bombers in 1943 during World War II. Andrea Doria, meanwhile, remained in service until 1911 when she was converted into a depot ship. After Italy entered World War I in May 1915, she was reactivated as a guard ship and based in Brindisi. After the war, she was converted into a floating oil tank before being sold for scrap in 1929.[43][44]

| Ship | Armament[43] | Armor[43] | Displacement[43] | Propulsion[43] | Service[43] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Ruggiero di Lauria | 4 × 432 mm guns | 451 mm (17.75 in) | 10,997 long tons (11,173 t) | Two shafts, compound steam engines, 16 to 17 knots (30 to 31 km/h; 18 to 20 mph) | 3 August 1881 | 1 February 1888 | Sunk by bombers, 1943 |

| Francesco Morosini | 4 December 1881 | 21 August 1889 | Sunk as a target, 1909 | ||||

| Andrea Doria | 7 January 1882 | 16 May 1891 | Broken up, 1929 | ||||

Re Umberto class

Brin returned to the naval ministry in 1883, which allowed his design preferences to prevail when the next class of ironclads were ordered that year.[40] The new design, for the Re Umberto class, followed the same basic lines as the Italias: Brin emphasized a very large displacement, light armor, and high speed.[45] Unlike Brin's earlier designs, however, the new ships abandoned the amidships en echelon arrangement of the guns in favor of a centerline arrangement, with one turret fore and aft. They also adopted significantly smaller British-built main guns, the same BL 13.5-inch gun used in the very similar British Admiral class. Sardegna, the third and final member of the class, adopted triple-expansion engines, the first time such machinery was used in an Italian capital ship. Sardegna was also one of the first warships equipped with Marconi's new wireless telegraph.[46]

The Re Umbertos saw service with the Italian fleet through the early period of their careers, though the more modern pre-dreadnought battleships of the Ammiraglio di Saint Bon and Regina Margherita classes had begun to enter service by the mid-1900s.[47] Accordingly, the three Re Umbertos were reduced to reserve status in 1905.[48] They were reactivated during the Italo-Turkish War, where they were extensively employed as coastal bombardment vessels in the North African campaign. There, they shelled Ottoman defenses, supported Italian troops holding the city of Tripoli, and shelled ports under Ottoman control.[49] Sicilia became a depot ship after the war, and once Italy entered World War I, Sardegna and Re Umberto became guard ships in Venice and Brindisi, respectively. In 1918, Re Umberto was converted into an assault ship, mounting numerous light guns in place of her original armament for a planned attack on the Austro-Hungarian base at Pola, but the war ended before it could be carried out. She was broken up in 1920, followed by the other two members of the class in 1923.[50]

| Ship | Armament[43] | Armor[43] | Displacement[43] | Propulsion[43] | Service[43] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Re Umberto | 4 × 343 mm (13.5 in) guns | 102 mm | 15,454 long tons (15,702 t) | Two shafts, compound steam engines, 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h; 21.3 mph) | 10 July 1884 | 16 February 1893 | Broken up, 1920 |

| Sicilia | 3 November 1884 | 4 May 1895 | Broken up, 1923 | ||||

| Sardegna | 24 October 1885 | 16 February 1895 | |||||

Notes

- Ordovini et al., p. 328

- Gardiner, pp. 334–335, 337

- Greene & Massignani, pp. 217–222

- Wilson, pp. 219–241

- Sondhaus (2001), p. 112

- Gardiner, p. 337

- Ordovini et al., p. 334

- Gardiner, pp. 335, 338

- Greene & Massignani, p. 232

- Wilson, pp. 232–241

- Gardiner, p. 338

- Sondhaus (1994), p. 50–51

- Ordovini et al., p. 338

- Wilson, pp. 220–233, 236–242

- Greene & Massignani, pp. 232–233

- Gardiner, pp. 335, 339

- Ordovini et al., p. 342

- Wilson, pp. 234–238, 240, 247

- Ordovini et al., pp. 343–344

- Gardiner, p. 339

- Sondhaus (1994), p. 44

- Ordovini et al., p. 348

- Gardiner, pp. 336, 339

- Gardiner, pp. 335, 339–340

- Ordovini et al., p. 354

- Wilson, pp. 223–225, 232–241, 245

- Greene & Massignani, p. 237

- Gardiner, pp. 337–340

- Ordovini et al., p. 358

- Gardiner, p. 340

- Greene & Massignani, p. 394

- Gardiner, pp. 340–341

- Clarke & Thursfield, pp. 202–203

- Sondhaus (1994), pp. 66–67

- Silverstone, p. 297

- Gardiner, p. 341

- Gibbons, p. 106

- Beehler, p. 47

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 255

- Sondhaus (2014), p. 99

- Gardiner, pp. 340–342

- Sondhaus (2014), pp. 107–108, 111

- Gardiner, p. 342

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 255–256

- O'Hara, Dickson, & Worth, p. 180

- Gardiner, pp. 29, 342

- Gardiner, pp. 342–343

- Brassey, p. 45

- Beehler, pp. 19–20, 47–48, 81, 90–91

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 256

References

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1905). "Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 40–57. OCLC 937691500.

- Clarke, George S.; Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation, or, Naval Warfare and Imperial Defence. London: John Murray. OCLC 640207427.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books, Ltd. ISBN 0-86101-142-2.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-938289-58-6.

- O'Hara, Vincent; Dickson, David; Worth, Richard (2013). To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-082-8.

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio; Sullivan, David M. (December 2014). "Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part I: The Formidabile, Principe di Carignano, Re d'Italia, Regina Maria Pia, Affondatore, Roma and Principe Amedeo Classes". Warship International. Vol. 51 no. 4. pp. 323–360. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2014). Navies of Europe. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86978-8.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.