Libagon

Libagon, officially the Municipality of Libagon (Cebuano: Lungsod sa Libagon; Tagalog: Bayan ng Libagon), is a 5th class municipality in the province of Southern Leyte, Philippines. According to the 2015 census, it has a population of 15,169 people. [3]

Libagon | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Libagon | |

Rizal Park of Libagon | |

Seal | |

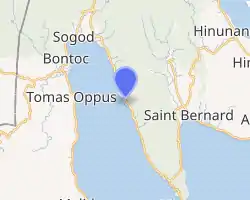

Map of Southern Leyte with Libagon highlighted | |

OpenStreetMap

| |

.svg.png.webp) Libagon Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 10°18′N 125°03′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) |

| Province | Southern Leyte |

| District | 2nd District |

| Founded | 1913 |

| Barangays | 14 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Bayan |

| • Mayor | Sabina Ranque |

| • Vice Mayor | Elizabeth Saldivar |

| • Representative | Roger G. Mercado |

| • Electorate | 10,729 voters (2019) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 98.62 km2 (38.08 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 150 m (490 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 15,169 |

| • Density | 150/km2 (400/sq mi) |

| • Households | 3,162 |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 5th municipal income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 42.24% (2015)[4] |

| • Revenue | ₱60,763,992.51 (2016) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 6615 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)53 |

| Climate type | tropical rainforest climate |

| Native languages | Boholano dialect Cebuano Tagalog |

| Website | www |

It is the home the province's frontier mountain, Mount Patag Daku.

Libagon celebrates its town fiesta every 8th day of December, the feast of Immaculate Concepcion. Another fiesta that is celebrated by the Libagonians is the feast of the Virgin of Mount Carmel every July 16.

The people's main sources of income are copra, abaca, farming, and fishing.

Barangays

Libagon is politically subdivided into 14 barangays.

- Biasong

- Bogasong

- Cawayan

- Gakat

- Jubas (Poblacion)

- Magkasag

- Mayuga

- Nahaong

- Nahulid

- Otikon

- Pangi

- Punta

- Talisay (Poblacion)

- Tigbao

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 4,642 | — |

| 1918 | 5,719 | +1.40% |

| 1939 | 6,318 | +0.48% |

| 1948 | 7,173 | +1.42% |

| 1960 | 7,891 | +0.80% |

| 1970 | 9,231 | +1.58% |

| 1975 | 9,519 | +0.62% |

| 1980 | 10,516 | +2.01% |

| 2010 | 14,352 | +1.04% |

| 2015 | 15,169 | +1.06% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [3] [5] [6][7] | ||

Climate

| Climate data for Libagon, Southern Leyte | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28 (82) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 78 (3.1) |

57 (2.2) |

84 (3.3) |

79 (3.1) |

118 (4.6) |

181 (7.1) |

178 (7.0) |

169 (6.7) |

172 (6.8) |

180 (7.1) |

174 (6.9) |

128 (5.0) |

1,598 (62.9) |

| Average rainy days | 16.7 | 13.8 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 23.2 | 26.5 | 27.1 | 26.0 | 26.4 | 27.5 | 24.6 | 21.0 | 268.6 |

| Source: Meteoblue [8] | |||||||||||||

History

It was said that Libagon got its name from a derivative or distorted word of the dialect, libaong, which means a small depression of the ground. Spanish authorities mistook the reference to the ground fault on the land being tilled as the name of the place. It has since been known by that name, Libagon.

The Dagohoy revolt prompted more Boholanos to settle the southern towns of Leyte, in particular in Hilongos, Bato, Matalom, Maasin, Macrohon, Malitbog and Hinunangan. Sometime in 1771, seventeen families from the different towns of Bohol migrated in the southeastern coast of Sogod. Led by Marciano Escaño, Agun Espedilla, Fernando Escueta ( Estuita), Mariano Evailar (Yballar), Lazaro Idhaw (now spelled as Idjao), Jose Endriga, Soldiano Arot, Fausto and Agustin Enclona (some families changed their spelling Encluna), Rosendo Evalin (Ybalen), Mauro Escamilla (Escabillas), Laurente Edillo, Domingo Espinosa, Francisco, Felipe and Tiburcio Egina, they founded the visita[satellite barrio with chapel] of Libagon. Andres Espina, a resident of Tamolayag [now Padre Burgos town], Malitbog, was invited to instruct the children how to read and write. Despite of its growing population, Libagon was only recognized as a visita of Sogod sometime in 1850.[13 Gan, Edito. "Sogod of our Memories: A Special History-Genealogy Account", Sogod Municipal Hall, Sogod, Southern Leyte]

The early known settlers of Libagon were of Bol-anon ancestry (Boholano people). The settlers' first chosen leader of Libagon was Domingo Mateo Espina. He was the son of Agustin Mateo Espina and Francisca Barbara and the grandson of Pedro Espina of Duero, Bohol. Espina's wife, Potenciana Escaño, was called Capitana Potenciana by townsfolk, in recognition of her role as First Lady of Libagon. The town of Libagon was founded in 1845.[9][10] At this point in the history of the municipality, the barrios or barangays under Libagon included Sogod and Bontoc at the farthest north and Punta at the farthest south. The Poblacion comprised two barangays: Jubas (at the south) and Talisay (at the north).

By March 1870, Don Gabriel Ydjao became the chief executive of Sogod and transferred the poblacion [town center] to Libagon. Since Ydjao was a native of that place, and probably because Sogod was far from his residence, he renamed Libagon as Sogod Nuevo (other historical accounts stated that Libagon was renamed Sogod Sur) and Sogod as Sogod Viejo (Sogod Norte). Ydjao also appealed to the parish curate, Padre Logronio, to transfer the parish church in Libagon, a year after Sogod was made a parish.[13] The church in Libagon would remain there until 1924, when a group of concerned Sogodnons plead to the bishop of Calbayog, the Most Reverend Sofronio Hacbang Gaborni, to return the seat of the parish in Sogod.

Don Patricio Tubia, a native of Buntuk, succeeded Ydjao during the 1876 elections as gobernadorcillo until 1878. Don Nicolas Idjao won the position of gobernadorcillo in the 1885 elections with Gabino Ellacer as teniente 2, Antonio Reyes as juez de sementeros, Rufino Espina as juez de policia, Ramon Espina as juez de ganados, Vicente Pajuyo as teniente 2 and Catalino Encinas as juez. The alguacils [municipal council or councilors] of Sogod Nuevo, at that period, were Julian Endriga, Raymundo Escabillas, Magdaleno Endriga and Pedro Ermogina(Hermogino). In the visita of Maak, Domingo Javier became the teniente del barrio, Gregorio Deberal as juez and Cirilo Banal and Evaristo Paña as police officers. Eleuterio Faelnar became the teniente del barrio of Sogod Viejo and Hipgasan with Mauro Catajoy and Potenciano Espina as juezes, and Jose Singson and Ariston Meole (now spelled as Miole) as police officers. Florentino Flores became the teniente del barrio of Buntuk with Francisco Cabilin and Fabian Ballena as juezes, and Dionisio Resma and Victor Jomor as police officers.[13] By 1887, Don Eleuterio Falenar, who once served as the teniente del barrio of Sogod, assumed as gobernadorcillo.[13]Borrinaga, Rolando (September 25–28, 2000). "Leyte: A Forgotten Symbol of Resistance Movements in the Visayas". http://www.oocities.org. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

Don Cipriano Lebiste (now Leviste, real name Tomas Jabonillo) became the gobernadorcillo of Sogod from 1889 to 1891. The members of the municipal council under Lebiste's administration were Eugenio Destrisa (some families spelled it as Destreza or Destriza), Felix Entino, Magdaleno Dagaas, Catalina Idjao, Pedro Bellesa, Patricio Tubia, Victoriano Godes, Lucio Dagaas and Agustin Ballina.[8]

When Don Luis Espina became gobernadorcillo from 1891 to 1893, the municipal council was composed of Buenaventura Gimenes (now spelled as Jimenez), Bernardo Endriga and Damaso Amongan as subalterno tenientes and Anastacio Ylan, Calexto Montanes, Protacio Elejorde and Carlos Ymluna (some families spelled it as Encluna or Enclona) as police officers. During Espina's incumbency, the visita of Maak was reduced to a sitio of barrio Consolacion with Antonio Cañete as the teniente 1, Gregorio Debera (now spelled as De Vera or De Veyra) as teniente 2, Rosales Bonot and Leoncio Cocido as juezes; and Eugenio Demosmog and Pantaleon Dejarme as police officers. With Maak's status being demoted, Sogod Viejo was also placed under the jurisdiction of the visita of Hipgasan with Crispulo Cabales as teniente 1, Domingo Bellesa as teniente 2, Mauro Catajoy as juez 1, Tranquilino Dagohoy as juez 2, and Victoriano Camba and Juan Javier as police officers. In Buntuk, Felipe Aguilar and Felix Entino assumed the position of tenientes 1 and 2 while Graciano Samaño and Antonio Arguelles were designated as juezes and Leoncio Resma as police officer.[8]Gan, Edito. "Sogod of our Memories: A Special History-Genealogy Account." Sogod, Southern Leyte: Sogod Local Government Unit

By 1893, Sogod was again headed by Don Nicolas Idjao with Crisante Pajuyo, Dimas Yndico (now spelled as Endico), Macario Ylang and Mauricio Sembrano as tenientes, Patricio Tubia as juez de sementeras, Luis Espina became the juez de ganados, Buenaventura Gimenez as juez de policia, and Felipe Paitan, Pedro Ralo (now Rale), Enrique Tiguetigue (now Tikistikis) and Fruto Egina as police officers.[8]Gan, Edito. "Sogod of our Memories: A Special History-Genealogy Account." Sogod, Southern Leyte: Sogod Local Government Unit

At some point in time, possibly during the years following 1845 until 1885, Libagon was deemed as a barrio of Sogod, together with Bontoc and Consolacion. In 1885, Nicolas Idjao was elected as gobernadorcillo and transferred the poblacion of Sogod to Libagon, 22 kilometres (14 mi) from Sogod. Then, he renamed Libagon as Sogod Nuevo or Sogod Del Norte while Sogod as Sogod Viejo or Sogod Del Sur. After twelve years of power, the poblacion was restored to Sogod for a while when Benito Faelnar was appointed as capitan municipal of Sogod. But in 1904, Ladislao or "Estanislao" Decenteceo was elected and transferred the poblacion to Barangay Consolacion, a barrio 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Libagon. However, in 1912, the poblacion was again transferred to Sogod when Vicente Cariño took office in that year.

On 16 October 1913, Libagon and Sogod were finally separated into two independent towns – Libagon (14 barrios) and Sogod (45 barrios). The challenges of an increasing population necessitated the division. The new Libagon was under the administration of the new Presidente Municipal, Mariano L. Espina.[11]

Language

The Cebuano language is either commonly spoken in Libagon or the Boholano dialect (Binol-anon) although there are some slight linguistic variation maybe in form, meaning or context. The Filipino language (or Tagalog) and English are taught in Elementary and High School.

Religion

Libagonons (or Libagonians) are predominantly Roman Catholic.

Feasts

The town celebrates its annual fiesta in honor of their patron saint, the Blessed Virgin Mary of The Immaculate Conception on December 8. She is also the principal patroness of the Philippines. Other main Catholic holy days, including the local feasts of barangays, are observed throughout the year.

Besides the main fiesta on 8 December, every 16 July, rain or shine, Libagonians also celebrate the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. They have a commending devotion to Mother Mary and a firm belief in Mary's general aid and prayerful assistance. The day after the feast, the traditional Pangilis is held. [Pangilis from the root word "ilis" meaning "change"]. On the 17th (July), at the break of dawn, the sounding of a bugle early in the morning to awake people, or dayana in the dialect, is carried out as a custom observed through the years to start-off the Pangilis solemnization and festivity. ["Dayana" etymology: Spanish: diana: reveille]. The former ermano-ermana hand over the holy image of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel to the home of the succeeding (h)ermano or (h)ermana mayor for the following year's fiesta in a procession joined by townsfolk of Libagon mostly from the poblacion. Before the Pangilis, devotees (Carmelitas or Carmelites) who pledge for one's support for the coming year's celebration are also enlisted. Then after the street parade, immediately begins a joyous street dancing that ends on or before midnight. This affair is usually led by that year's chosen (with solicitation) or at times designated "King and Queen" of Pangilis. In recent celebrations, a Pangilis Idol is determined in a contest of talents usually in dancing dressed in their own imaginative, artistic, colorful and, at times, bizarre costumes.

Similarly, these two feasts feature the colorful karo (carriage) that carries the holy image of the Blessed Virgin Mary on a ceremonial procession after the novena and mass held on the evening before the feast day. Both the karo and the church's altar are usually adorned with creative floral arrangements.

The Parish of the Immaculate Conception

The first church and convent built by Libagonons were of wooden structure. "The tradition of building wooden churches date back from the Middle Ages until the turn of the 18th century. The skills, knowledge and experience to build an ample log structure were performances out of the ordinary". (See: Wooden Churches of Maramures). As commonly practiced in the past, the construction of the church, chapel, convent and the town hall was made possible through bayanihan, a spirit of communal unity or effort to do a particular goal. A resident of proper age can volunteer at least a day in a week to a month to help or work in the construction. Usually on a Saturday, the volunteers ascended the mountains to look for timber for the church's pillars and some wood used in other means, like wood joints, posts, floors, etc. The wood found were Narra trees (pterocarpus), Molave trees (vitex parviflora), White Lauan (shorea contorta) and other rainforest trees in the forested mountains of Libagon. The largest pillars were huge trees bigger than the circumference of a man's (or two men's) outstretched arms. The task of dragging down the trees (with very strong ropes on both ends) from the mountainous jungle on narrow access was indeed a hazardous challenge to the men. In like manner, another group of volunteers brought gongs and drums to tap a repeated rhythmic beat and synchronized the pushing and pulling down of the timber while together they howled, "HIIIIBOOOYYYY...." While on an abrupt slope, restraining the heavy log is crucial to prevent it from running over someone and avoid breakage of the tree. Each of them brought their own food and an ample amount of coconut wine (tuba) stored in a baler shell or bamboo container to quench their thirst. Despite all these, the bayanihan spirit of the Libagonons rose above the arduousness of the endeavor and wiped out any exhaustion they felt.[12]

Aside from timber, the church's foundation were made of crushed rocks, stones and sand that were hauled and made into tablets of stone and framed as walls. The stone walls stood nearly at 5 to 6 feet tall and laid on top with lumber that continued up to the ceiling. The groundwork for every column was deep and durable. As cement, they used stones and sand daubed with whipped egg whites mixed with lime to reinforce the pillars.[13] The floor tiles were specifically requested from Barcelona, Spain. The belfry stood high with three large church bells. Each piece, when rang, upended and plunged causing a loud sound that can be heard as far as San Isidro, Banday, and areas across Sogod Bay. Unfortunately, during World War II this wooden church was burned down by the Japanese invaders and was rebuilt into its present structure with a more modernized architecture but twice smaller than the original. They tried to reposition the original columns to rebuild it but they were unexpectedly tough to demolish. They instead had to severe the posts from the surface.[14]

The first ever parish priest of Libagon was Padre Don Tomas Logroño from Inabanga, Bohol. He graduated from Colegio-Seminario de San Carlos of Cebu (presently known as San Carlos Major Seminary of Cebu). He arrived in Libagon in June 1870. He was instrumental in the materialization of Libagon's earliest parish and convent. He bought articles, stuff and other religious items needed in the church. He served as Libagon's parish priest for 12 years. In April 1882, he was destined to the town of Macrohon, Southern Leyte until his demise on October 21, 1901.[14]

Local government

List of former municipal leaders

During the early years of the Spanish regime, the town's leader was addressed as the "Capitan" similar to Alcalde Municipal, or Presidente Municipal, and presently, Municipal Mayor. On record, the succession of leaders in Libagon from Spanish to American regimes to Postwar (Philippine Independence) 1946-1965 was as follows:[15]

- Capitan Domingo Espina

- Capitan Pedro Espina

- Capitan Felix Espina

- Capitan Estanislao Decenteceo

- 1870-Gobernadorcillo-Don Gabriel Ydjao

- 1885-Gobernadorcillo-Don Nicolas Idjao

- 1889-1891-Gobernadorcillo-Don Cepriano Lebiste (Tomas Jabonillo)

- 1913-1916 ...Presidente Municipal Mariano L. Espina

- 1917-1920 ...Presidente Municipal Macario Logroňo

- 1921-1928 ...Presidente Municipal Mariano L. Espina

- 1929-1931 ...Presidente Municipal Fabio Bayon

- 1931-1932 ...Presidente Municipal Isidro Pajuyo

- 1933-1940 ...Municipal Mayor Rito Monte de Ramos

- 1941-1944 ...Municipal Mayor Gregorio E. Edillo

- 1944-1945 ...Municipal Mayor Francisco E. Espina

- 1945-1946 ...Municipal Mayor Gregorio E. Edillo

- 1946-1947 ...Municipal Mayor Joaquin Siega

- 1948-1951 ...Municipal Mayor Francisco E. Espina

- 1952-1955 ...Municipal Mayor Agustin E. Espina

- 1956-1959 ...Municipal Mayor Mario E. Espina

- 1960-1963 ...Municipal Mayor Rito Monte de Ramos

- 1964-1967 ...Municipal Mayor Mario E. Espina

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines (1942–1945), Petronilo "Liloy" Ebarle was appointed as the Municipal Mayor from 1942-1944. However, the guerrillas alluded him as a "puppet mayor". Though Mayor Ebarle held the Japanese-appointed position, Mayor Gregorio E. Edillo also continued to be the official leader under the authority of the Philippine Commonwealth with the United States. On the other hand, the people also recognized the command of the guerrilla forces of Leyte or the Leyte Area Command under Coronel Ruperto Kangleon, and supported as well the supervision of the Volunteer Guards in the town level. There were only two leaders of the Volunteer Guards in Libagon. The first was Lieutenant Francisco Barros, followed by Francisco "Dodo" Espina.[16] And the only Libagonian officials of the Leyte Area Command (LAC) were Lieutenant Catalino "Nongnong" E. Soledad, Lieutenant Feliciano "Lily" A. Espina and Lieutenant Marcelo "Celing" E. Espina, who were also officers of USAFFE (U.S. Army Forces in the Far East). These three brave Libagonians fought in the Battle of Bataan which represented the most intense phase of Imperial Japan's invasion of the Philippines during World War II. Unfortunately, of the three brave men, only Marcelino Espina did not make it back to his hometown, Libagon. His body was left on the battlefield of Bataan. He was the younger brother of Francisco "Dodo" Espina who became the town's Mayor for two terms. Like Celing, many valiant guerrillas from Libagon died during the war. A Memorial Stone (Ang Bato sa Paghandum) was built in memory of these heroic men of Libagon. All their names were engraved on granite to honor their lives and monumentalize their memory and courageous deed.[17] The Memorial Stone now stood in the midst of Libagon Rizal Park.

The Contemporary period includes the final years of the Third Republic (1965–72) and the entirety of the Fourth Republic (1972–86) to the succeeding years following the 1986 People Power Revolution.

- 1968- 1979 ...Municipal Mayor Salvador M. Resma

- 1979- 1986 ...Municipal Mayor Domingo P. Espina

- 1986- 1992 ...Municipal Mayor Rogato J. Paitan

- 1992- 2001 ...Municipal Mayor Domingo P. Espina

- 2001- 2010 ...Municipal Mayor Rizalina Espina née Bañez (formerly a.k.a. Inday S. Bañez)

- 2010 – present. Municipal Mayor Oliver E. Ranque

Attractions

Libagon is the home of exotic and unique natural areas that are excellent for ecotourism and adventure travel. Perhaps the most defining experience in adventure travel is found in Libagon. However, “a walk through the rainforest is not eco-tourism unless that particular walk somehow benefits that environment and the people who live there. A rafting trip is only eco-tourism if it raises awareness and funds to help protect the watershed.” (Untamed Path)

Patag Daku Rain Forest

Patag Daku is located in Libagon, Southern Leyte, particularly in the upper or mountainside of the poblacion in Talisay.

Patag Daku, in English, means "big plain". It is certainly big but is never quite plain. It is actually a valley so dense in vegetation that novice campers and mountaineers will never come in or out without an experienced guide leading the way. But the trek to the valley comes big in every way. In mountaineering parlance, it is a major climb. Not the leisurely stroll that one might expect, the climb is an arduous six-hour journey through a maze of trees, ferns, moss, grass and big trees.[18]

Patag Daku, the mossy forest more than 500 hectares of unexplored, uncharted wilderness, fraught with dangerous tales of huge snakes and wild animals.[19]

Uwan-Uwanan Falls

Uwan-uwanan falls is located in barangay Kawayan, Libagon. The gorge is a world-class adventure wonder. Climbing, swimming and trekking rolled into one.[20] It will take a two-hour trek to the mountains, rappelling and climbing bamboo ladders within cascading falls before you reach the top.[21]

Uwan-uwanan, literally means "resembling a rainfall" because the two-hour track entails an enchanting encounter of an "uwan-uwanan ". And at the top, photo enthusiasts are in for a marvelous treat. At exactly 12:00 noon when the sun is directly above the middle of the narrow opening at the gorge, the natural light is awe-inspiring as it dramatically illuminates the whole area resembling a magnificent altar in a cathedral or a place of worship.

Hindag-an Falls

Hindag-an Falls is a natural wonder found in St. Bernard, Southern Leyte. Just about 1 kilometer away from the roadside. The place displays natural waterfalls with man-made pools. In every waterfall is a pool of particular depth. The deepest was about 10–15 feet wherein you need to jump from above the rocks to get to the pool. There is also a pool for children about 2 ft. and also a water slide.

Pangi Black Sand Beach

The beach in barangay Pangi is of fine black sands usually great for swimming, hiking and ecotourism. Other black sand beaches can also be found in more places than anyone thinks, like the famous black sand beaches of Polynesia, Indonesia, Iceland, the Caribbean islands and the Punaluu Black Sand Beach in Hawaii, were created virtually instantaneously by the violent interaction between hot lava and sea water.

The suspicion of a volcano close to Libagon may explain the black sand beach formation in barangay Pangi. But there is no exact evidence on this suspicion as verified by the concerned agency.[22]

See also: Black sand and Black Sand Beach

Biasong Springs

Biasong Springs is one of the oldest spring in Southern Leyte. It is located in the barangay of Biasong. The clear spring water is collected into a man-made basin or pool.

The place is a favorite of the locals providing cool mountain spring water. A pool that has been the site of many happy occasions: birthday picnics, homecoming celebrations, etc. It has perhaps the sweetest mineral spring water in the province and most uncontaminated source.[23]

Peter's Mound

Peter's Mound, a fascinating dive site, is a sea mound located just 200 meter offshore from barrio Otikon.[24]

A sea mound just 200 m. (650 ft.) offshore, is a cleaning station for large pelagics. Animals to see are: wrasse, grouper, sweetlips, surgeons, fusiliers, tuna, and jacks together with other species of reef fish.[25] The deep starts at 10m and drops off to over 40m. The currents can be strong which means that coral life is profuse.[26]

Municipal Town Hall

Libagon has a century-old and well-preserved Spanish style municipal hall. The structure gives a glimpse of the town's rich heritage. It is amongst Southern Leyte's premier historical sites and landmarks - the pride of Southern Leyte.[27]

Bulwark (Ang Balwarte)

This is the only memorial left of the Lungsod-Daan or the original location of the town center of Libagon. It is made of boulders or tablets of rock, limestone and gravel. This structure is made strong and formidable as a defensive fortification against the Moros (Muslim) from the big island of Mindanao. See also Moro people (section: Spanish period).

Strategically located, the edifice is overlooking Sogod Bay and the two deltas of the islands of Limasawa and Panaon. The Bulwark or Balwarte at the old town center is near the big river named Tubig-Daku, below and adjacent to the existing cemetery. This is also where the Japanese soldiers camped during World War II.

Old Pantalan (Seaport)

The ruins of the old pantalan or seaport still stand along the shores of the Poblacion in Jubas. Recently, the entire seacoast along Sogod Bay is transformed into a "park by the bay" also commonly referred to as the Boulevard in Jubas ideal for walks and for viewing the sunset while fishermen on their lighted bancas or boats scatter all over the bay. This is seen most specially during peak fish season.

Besides, the beautiful sunset along Sogod Bay, the whale-sharks in Southern Leyte are simply at home in Sogod Bay. Whale-sharks or Rhyncodon typus are popularly known locally as iho-tiki. Recent sightings confirm that whale-sharks actually are all over Sogod Bay. They were spotted in San Francisco, Southern Leyte, as well as in Limasawa, Malitbog, Libagon, Sogod, Pintuyan and even as far as San Ricardo. In fact, they had long been ordinary fare for small fishermen. People have gotten used to them that young boys ride on their backs as they scour for plankton along the village shores. Though, there is no 100 percent guarantee to spot a whale-shark in Sogod Bay. It takes proper timing, good weather, and a huge amount of luck to see one. Patience is the name of the game. The best time to see whale-sharks in Southern Leyte is April and May.[28]

Libagon Rizal Park

Like most local governments from Luzon to Visayas and Mindanao, a Rizal monument is erected to commemorate the Philippines' national hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, regarded as the foremost Filipino patriot. The Rizal monument stands at the Libagon Rizal Park, a significant landmark of Libagon located strategically in the midst of the poblacion.

Education

The Parish Convent cum Libagon High School

Like the old church, several large pillars made the convent strong. The large convent was built beside the church. Unlike the old sanctuary, the old friary was providentially spared from being burned down during the war. The structure defied many strong typhoons, hurricanes, and vigorous quakes—a token of the superior groundwork.

Earlier, the friary being the home of the parish priest and church servants was also used as the house of the first Catholic educational institution of Libagon and the first and only High school. The limited funds to set up a Secondary school moved the founders to appeal to Bishop Manuel Mascariñas (in Palo, Leyte) for his approval to use some of the rooms of the convent. Because Libagon High School was dedicated to be a Catholic institution the Bishop acceded to the request and even allowed the High School to use the church's plaza as well.

Initially known as the "Libagon High School, Inc.", the establishment basically taught Catechism – training for the young Catholic faithful with questions and answers about the essentials of Catholic faith and doctrine so that they could understand easily their faith. Besides the 3 R's (Reading, Writing and Arithmetic), the Spanish language was normally taught at that time. Music, however, was especially instructed. Musicians, songwriters, singers and choirmaster were trained for the church's choir. The same musicians completed the town's band that was well known among other bands in the province.

The Bureau of Private Schools suggested that the establishment be given another name that would signify it as a non-public school. Thus, the Board of Trustees signed a resolution renaming the High School as, "Libagon Academy." Consequently, they renamed the corporation as, "Libagon Academy Foundation, Inc."

In another resolution the Board decided to make the Academy a non-profit organization. All proceeds (if there was any at all) were used to improve the schoolhouse. The modest tuition enabled all primary school graduates to continue their education in High school in their own town instead of spending more to attend school in nearby provinces, or stop and work in the farm or simply marry. However, the low tuition prevented the academy to some earnings, thus the resolution. After all, the many professionals – the teachers, doctors, lawyers, engineers, auditors, seamen, nurses, and many other professionals as products of Libagon Academy—became undoubtedly the biggest dividend of a simple and unassuming town, such as, Libagon.

The Libagon Academy was yet another product of the bayanihan spirit among Libagonians. The forerunners and shareholders, who were also parents and widowed mothers after the war, were driven with the same purpose to give reasonable education to their children. And as donation, they pulled together some of their own personal belongings (like pocket books, magazines, notebooks, etc.) to the academy. These admirable men and women were motivated by the selfless efforts of the founders of the first Libagon High School (renamed Libagon Academy) despite stiff disapproval from some factions.

The founding Board of Trustees were:

- Francisco E. Espina - President

- Mario E. Espina - Vice-President

- Nemesio A. Egina - Secretary-Treasurer

- Bibiano K. Lasala - Auditor

- Brigida Gozo-Escuita - Member

- Vivencio Lopez - Member

The pioneer members of the Faculty were:

- Felix B. Endriga - Director / Principal / English Instructor

- Carmen N. Endriga - Biology & Tagalog Instructor

- Purificacion Ebarle - English Instructor

- Perpetou D.Margallo - History Instructor

- Jesus Cellan - Science Instructor

- Mario E.Espina - Religion Instructor

- Imelda Espinosa - Librarian

On June 1949, Libagon Academy opened its doors for its first day of classes. The institution remained to be the only premier Catholic educational organization of the municipality of Libagon.[29]

Transportation

Ordinarily, the habal-habal(s) or single motorcycles are used as modes of transportation in crossing Sogod and to other distant and mountainous areas. Sogod is the major terminus in the south central portion in Leyte Island. It is the vital link in connecting Visayas to Mindanao. The buses, jeepneys, and for-hire vans terminate from Sogod to Maasin City, Ormoc City, Tacloban City, Bato-Hilongos, Liloan (by way of Libagon), Hinunangan and Silago.

The Libagon Highway is part of the Pan-Philippine Highway, also known as the Maharlika Highway (AH26). It is a 3517 km network of roads, bridges, and ferry services that connect the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao in the Philippines, serving as the country's principal transport backbone. The northern terminus of the highway is at Laoag City, and the southern terminus is at Zamboanga City.

In addition, traveling to Manila from Libagon approximately takes 24 hours by bus along with ferry from Northern Samar to Matnog. The trip is a scenic interprovincial ride. Philtranco buses are long known to serve this route.

Telecommunication

Mobile:

- Serviced by Smart Communications

- Serviced by Globe Telecom

- Serviced by Sun Cellular

Internet:

- Wireless Internet through SMART Network (Smart Bro)

- Wireless Internet through Globe Network (Globe Tattoo)

Cable Television:

- Dream satellite TV

References

- Municipality of Libagon | (DILG)

- "Province: Southern Leyte". PSGC Interactive. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Census of Population (2015). "Region VIII (Eastern Visayas)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "PSA releases the 2015 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Quezon City, Philippines. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region VIII (Eastern Visayas)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Region VIII (Eastern Visayas)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. NSO.

- "Province of Southern Leyte". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Libagon, Southern Leyte : Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Meteoblue. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Espina, Francisco Sr., Ang Lungsod sa Libagon, 1985.

- Espina 1985, Gibalhin Ang Lungsod, p. 3.

- Espina 1985, Nabahin sa Duha ang Lungsod sa Libagon, p. 13.

- Espina, Francisco Sr., Gitukod Ang Simbahan, Kombento Ug Balay-Lungsod, p.5.

- Espina, Francisco Sr., Gitukod Ang Simbahan, Kombento Ug Balay-Lungsod, p.6.

- Espina, Francisco Sr., Ang Unang Pari sa Libagon, p.7.

- Espina 1985, Mga Punoan sa Libagon, p. 21.

- Espina 1985, Mga Punoan sa Libagon, p. 22.

- Espina 1985, Mga Opisyales sa Leyte Area Command, p. 39.

- "Patag Daku in Libagon". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- "Conquering Patag Daku". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

- "Southern Leyte".

- "The Amazing UWAN-UWANAN FALLS, Libagon, So. Leyte". Archived from the original on 12 March 2012.

- Chong, Joaquin. Suspicion of a Volcano Close to Libagon. Maasin City, Southern Leyte. p. 26.

- "Sogod Bay Tales & Images". Geocities.

- "Towns and Cities -SOUTHERN LEYTE (Region VIII:Eastern Visayas)-LIBAGON".

- "Dive sites in Leyte".

- "Southern Leyte Philippines Dive Sites Destination".

- "The Provincial Tourism Department Invites You to Visit Southern Leyte".

- "The Whalesharks of Southern Leyte". Tour Leyte. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010.

- Espina 1985, Natukod Ug Gibuksan Ang Libagon Academy, p. 44.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Libagon, Southern Leyte. |