Lateral medullary syndrome

Lateral medullary syndrome is a neurological disorder causing a range of symptoms due to ischemia in the lateral part of the medulla oblongata in the brainstem. The ischemia is a result of a blockage most commonly in the vertebral artery or the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.[1] Lateral medullary syndrome is also called Wallenberg's syndrome, posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) syndrome and vertebral artery syndrome.[2]

| Lateral medullary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Wallenberg syndrome, posterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome |

| |

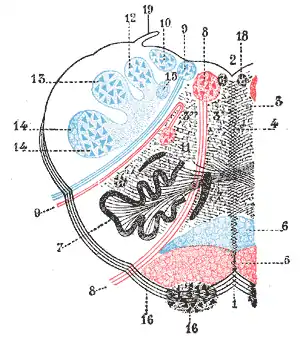

| Medulla oblongata, shown by a transverse section passing through the middle of the olive. (Lateral medullary syndrome can affect structures in upper left: #9=vagus nerve, #10=acoustic nucleus, #12=nucleus gracilis, #13=nucleus cuneatus, #14=head of posterior column and lower sensory root of trigeminal nerve and #19=Ligula.) | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Signs and symptoms

This syndrome is characterized by sensory deficits that affect the trunk and extremities contralaterally (opposite to the lesion), and sensory deficits of the face and cranial nerves ipsilaterally (same side as the lesion). Specifically a loss of pain and temperature sensation if the lateral spinothalamic tract is involved. The cross body finding is the chief symptom from which a diagnosis can be made.

Patients often have difficulty walking or maintaining balance (ataxia), or difference in temperature of an object based on which side of the body the object of varying temperature is touching.[2] Some patients may walk with a slant or suffer from skew deviation and illusions of room tilt. The nystagmus is commonly associated with vertigo spells. These vertigo spells can result in falling, caused from the involvement of the region of Deiters’ nucleus.

Common symptoms with lateral medullary syndrome may include difficulty swallowing, or dysphagia. This can be caused by the involvement of the nucleus ambiguus, as it supplies the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves. Slurred speech (dysarthria), and disordered vocal quality (dysphonia) are also common. The damage to the cerebellum or the inferior cerebellar peduncle can cause ataxia. Damage to the hypothalamospinal fibers disrupts sympathetic nervous system relay and gives symptoms that are similar to the symptoms caused by Horner syndrome – such as miosis, anhidrosis and partial ptosis.

Palatal myoclonus, the twitching of the muscles of the mouth, may be observed due to disruption of the central tegmental tract. Other symptoms include: hoarseness, nausea, vomiting, a decrease in sweating, problems with body temperature sensation, dizziness, difficulty walking, and difficulty maintaining balance. Lateral medullary syndrome can also cause bradycardia, a slow heart rate, and increases or decreases in the patients average blood pressure.[2]

Based on location

| Dysfunction | Effects |

| Vestibular nuclei | Vestibular system: Vomiting, vertigo, nystagmus |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle | Ipsilateral cerebellar signs including ataxia, dysmetria (past pointing), dysdiadochokinesia |

| Central tegmental tract | Palatal myoclonus |

| Lateral spinothalamic tract | Contralateral deficits in pain and temperature sensation from body (limbs and torso) |

| Spinal trigeminal nucleus & tract | Ipsilateral deficits in pain and temperature sensation from face |

| Nucleus ambiguus - (which affects vagus nerve and glossopharyngeal nerve) - localizing lesion (all other deficits are present in lateral pontine syndrome as well) | Ipsilateral laryngeal, pharyngeal, and palatal hemiparalysis: dysphagia, hoarseness, absent gag reflex (efferent limb—CN X) |

| Descending sympathetic fibers | Ipsilateral Horner's syndrome (ptosis, miosis, & anhidrosis) |

Cause

It is the clinical manifestation resulting from occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or one of its branches or of the vertebral artery, in which the lateral part of the medulla oblongata infarcts, resulting in a typical pattern. The most commonly affected artery is the vertebral artery, followed by the PICA, superior middle and inferior medullary arteries.

Diagnosis

Since lateral medullary syndrome is often caused by a stroke, diagnosis is time dependent. Diagnosis is usually done by assessing vestibular-related symptoms in order to determine where in the medulla that the infarction has occurred. Head Impulsive Nystagmus Test of Skew (HINTS) examination of oculomotor function is often performed, along with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assist in stroke detection. Standard stroke assessment must be done to rule out a concussion or other head trauma.[2]

Treatment

Treatment for lateral medullary syndrome is dependent on how quickly it is identified.[2] Treatment for lateral medullary syndrome involves focusing on relief of symptoms and active rehabilitation to help patients return to their daily activities. Many patients undergo speech therapy. Depressed mood and withdrawal from society can be seen in patients following the initial onslaught of symptoms.

In more severe cases, a feeding tube may need to be inserted through the mouth or a gastrostomy may be necessary if swallowing is impaired. In some cases, medication may be used to reduce or eliminate residual pain. Some studies have reported success in mitigating the chronic neuropathic pain associated with the syndrome with anti-epileptics such as gabapentin. Long term treatment generally involves the use of antiplatelets like aspirin or clopidogrel and statin regimen for the rest of their lives in order to minimize the risk of another stroke.[2] Warfarin is used if atrial fibrillation is present. Other medications may be necessary in order to suppress high blood pressure and risk factors associated with strokes. A blood thinner may be prescribed to a patient in order to break up the infarction and reestablish blood flow and to try to prevent future infarctions.[3]

One of the most unusual and difficult to treat symptoms that occur due to Wallenberg syndrome are interminable, violent hiccups. The hiccups can be so severe that patients often struggle to eat, sleep and carry on conversations. Depending on the severity of the blockage caused by the stroke, the hiccups can last for weeks. Unfortunately there are very few successful medications available to mediate the inconvenience of constant hiccups.

For dysphagia symptoms, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has been shown to assist in rehabilitation. Overall, traditional stroke assessment and outcomes are used to treat patients, since lateral medullary syndrome is often caused by a stroke in the lateral medulla.[3]

Treatment for this disorder can be disconcerting because some individuals will always have residual symptoms due to the severity of the blockage as well as the location of the infarction. Two patients may present with the same initial symptoms right after the stroke has occurred, but after several months one patient may fully recover while the other is still severely handicapped. This variation in outcome may be due to but not limited to the size of the infarction, the location of the infarction, and how much damage resulted from it.[4]

Prognosis

The outlook for someone with lateral medullary syndrome depends upon the size and location of the area of the brain stem damaged by the stroke.[2] Some individuals may see a decrease in their symptoms within weeks or months. Others may be left with significant neurological disabilities for years after the initial symptoms appeared.[5] However, more than 85% of patients have seen minimal symptoms present at six months from the time of the original stroke, and have been able to independently accomplish average daily within a year.[6]

Epidemiology

The lateral medullary syndrome is the most common form of posterior ischemic stroke syndrome. It is estimated that there are around 600,000 new cases of this syndrome in the United States alone.[7] Those at the overall highest risk for lateral medullary syndrome are men at an average age of 55.06. Having a history of hypertension, diabetes and smoking all increase the risk of large artery atherosclerosis.[8] Large artery atherosclerosis is thought to be the greatest risk factor for lateral medullary syndrome due to the deposits of cholesterol, fatty substances, cellular waste products, calcium and fibrin. Otherwise known as plaque build up in the arteries.[9]

History

The earliest description of lateral medullary syndrome was first written by Gaspard Vieusseux at the Medical and Chirurgical Society of London describing the symptoms observed at the time. Adolf Wallenberg further reinforced these signs after completing his first case report in 1895. He was able to make an accurate localization of the lesion and soon after proved it following a postmortem examination. Wallenberg accomplished three more published articles about lateral medullary syndrome.[10]

Adolf Wallenberg

Adolf Wallenberg was a renowned neurologist and neuroanatomist most widely known for his clinical descriptions of Lateral Medullary Syndrome. He completed his doctorate at University of Leipzig in 1886. By 1928 he had spent 2 years (1886-1888) as an assistant at the city hospital in Danzig, 21 years (1907-1928) as the director of internal and psychiatric departments and 18 years (1910-1928) as a titular professor. In 1929, Wallenberg received the Erb Commemorative Medal for his work in the field of anatomy, physiology and pathology of the nervous system.[11]

Wallenberg's first patient in 1885 was a 38-year-old male suffering from symptoms of vertigo, hypoesthesia, loss of pain and temperature sensitivity, paralysis of multiple locations, ataxia and more. His background in neuroanatomy helped him in correctly locating the patient's lesion to the lateral medulla and connected it to a blockage of the ipsilateral posterior inferior cerebral artery. After the death of his patient in 1899, he was able to prove his findings after a postmortem examination. He continued his work with many patients and by 1922 he had reported his 15th patient with clinicopathological correlations. In 1938, Adolf Wallenberg was forced to end his career as a physician by the German occupation.[11] When the Nazis came to power, he was stripped of his research laboratory and forced to stop working because he was Jewish. He emigrated to Great Britain in 1938, then relocated to the United States in 1943.

See also

References

- Lui, Forshing; Anilkumar, Arayamparambil C. (2018), "Wallenberg Syndrome", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262144, retrieved 2019-03-11

- "Wallenberg syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- "Wallenberg Syndrome". Physiopedia. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- http://www.healthline.com/galecontent/wallenberg-syndrome

- wallenbergs at NINDS

- "Wallenberg Syndrome". Physiopedia. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- DeMyer, William (1998). Neuroanatomy. Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780683300758.

- "Wallenberg Syndrome". Physiopedia. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Atherosclerosis". American Heart Association. The American Heart Association. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- synd/1778 at Who Named It?

- Aminoff, Michael (29 April 2014). Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences (Second ed.). Tomah, WI: Academic Press. p. 744. ISBN 9780123851581. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- MRI of Lateral Medullary Infarction (Wallenberg) MedPix Images