Landing at Jacquinot Bay

The Landing at Jacquinot Bay was an Allied amphibious operation undertaken on 4 November 1944 during the New Britain Campaign of World War II. The landing was conducted as part of a change in responsibility for Allied operations on New Britain. The Australian 5th Division, under Major General Alan Ramsay, took over from the US 40th Infantry Division, which was needed for operations in the Philippines. The purpose of the operation was to establish a logistics base at Jacquinot Bay on the south coast of New Britain to support the 5th Division's planned operations near the major Japanese garrison at Rabaul.

| Landing at Jacquinot Bay | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War of World War II | |

.jpg.webp) Australian 6th Brigade troops unload stores at Jacquinot Bay. | |

| Location | 5.5666667°S 151.5°E |

| Commanded by | Raymond Sandover |

| Objective | Amphibious landing to secure the site for a planned base |

| Date | 4 November 1944 |

| Executed by | 6th Brigade |

| Outcome | Allied success |

Brigadier Raymond Sandover's 6th Brigade was directed to secure the Jacquinot Bay area. While the region was believed to be undefended, the initial landing was conducted by a combat-ready force comprising the reinforced Australian 14th/32nd Battalion protected by warships and with aircraft on standby. As expected, there was no opposition to the landing on 4 November and work soon began on logistics facilities.

Once a base was established at Jacquinot Bay, it was used to support Australian operations toward Rabaul. These were conducted in early 1945 in conjunction with advances on the northern side of New Britain. The campaign was effectively one of containment, isolating the larger Japanese force and allowing the Allies to conduct operations elsewhere.

Background

Geography

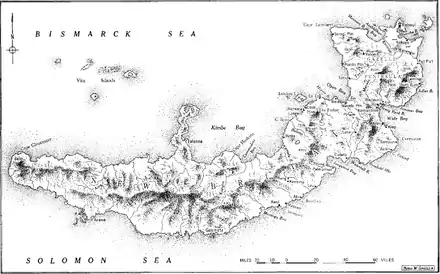

Jacquinot Bay lies on the south coast of the island of New Britain, to the east of Gasmata and the west of Wide Bay.[1] The southern part of the island (i.e. excluding the Gazelle Peninsula and the isthmus) is dominated by a densely forested central mountain range. The range rises to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and sits inland from a narrow coastal shelf.[2] In 1943–1944, there were numerous small villages and localities around the bay. The main ones were Cutarp, a coconut plantation which lay on a headland to the north-east, and Palmalmal which lay to the south-west. In between, the village of Pomio lay on the northern shores of the bay. There was a coconut plantation around the southern part of the bay at Wunung, which was bounded by two freshwater rivers to the north and south, and another plantation around Palmalmal. A Roman Catholic mission was located at Mal Mal, although it was reportedly abandoned at the time. The beach opposite Pomio was considered suitable for landing operations, but between Pomio and Wunung, there was dense rainforest along the coast. Between Wunung and Palmalmal, the beach was considered suitable for landings, with some shelter offered to smaller vessels close in.[3] There were only limited tracks around the region, and those that existed were assessed as not being suitable for motor traffic without improvement.[4]

The region's climate was described as "hot and humid", with exceptionally high rainfall.[5] The southern coastal region experienced a higher rainfall than the northern coast. The southern coast experienced a monsoon season during May to November, with the wettest period between July and September. Rain events were mainly at night or early morning. An Allied study completed in 1943 assessed average monthly rainfall at Palmalmal as 35.9 inches (910 mm) in July, 45.95 inches (1,167 mm) in August and 17.94 inches (456 mm) in September. In the last quarter of the year, rainfall was assessed as declining, with November (the month of the operation) averaging around 10.17 inches (258 mm). Temperatures at the time were recorded at Gasmata as ranging between 60 to 95 °F (16 to 35 °C), although minimum temperatures largely averaged between 74 to 76 °F (23 to 24 °C) and maximum temperatures averaged between 84 to 89 °F (29 to 32 °C). Humidity ranged between 75 and 85 percent. In terms of population, there were very few Europeans in the area prior to the war, with estimates ranging from 20 to 25. The indigenous population occupied several villages in the coastal area and the mountains, and were considered to form two main groups based around these areas.[6]

The area around Jacquinot Bay was part of the Australian Territory of New Guinea, which had been mandated in 1920, and was considered to be under government control prior to the Japanese invasion.[7] It formed part of the Gasmata sub-district, with a government and police post situated at Pomio, and was administered by an assistant district officer who reported to Rabaul. During the withdrawal of Allied forces from Rabaul in early 1942, the local population along the south coast had assisted Allied stragglers, and were believed to be supportive of the Allied cause, albeit pragmatic in their approach to the Japanese occupation.[6]

Strategic situation

During late 1943 and early 1944 Allied forces in the South West Pacific Area undertook Operation Cartwheel. This was a major offensive which aimed to isolate the main Japanese base in the area at Rabaul on the north-eastern tip of New Britain, and capture airstrips and anchorages which were needed to support a subsequent advance towards the Philippines.[8] During December 1943 and January 1944 United States Army and United States Marine Corps units successfully landed in western New Britain at Arawe and Cape Gloucester. Japanese forces in western New Britain suffered a further defeat at Talasea in March 1944. Securing the western island prevented the Japanese launching attacks against the flank of the main Allied offensive along the north coast of New Guinea.[9] Allied operations to secure the Huon Peninsula and the Markham–Ramu Valley, on the New Guinea mainland concluded in April 1944 with the capture of Madang.[10] The focus of Allied operations on the mainland then turned towards securing Western New Guinea. The Admiralty Islands were captured during a campaign which lasted between 29 February and 18 May 1944.[11] On Bougainville, a strong Japanese counter-attack had been repulsed in March 1944. A period of relative quiet followed until late 1944, after Australian forces relieved the US garrison (arriving from October).[12]

The Japanese Eighth Area Army, under General Hitoshi Imamura, was headquartered at Rabaul. Its area of operations encompassed the Solomon Islands chain (including Bougainville), mainland New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago (of which, New Britain was the largest island). It had suffered significant reversals on mainland New Guinea and in the Solomon Islands.[13] With the loss of western New Britain, Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) forces were concentrated in the north-east of the island on the Gazelle Peninsula to defend Rabaul against a direct attack.[14] The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) maintained a network of coastwatching stations along New Britain's coast. The Japanese garrisons and some local officials used brutality to try and rule the civilian population.[15] In March 1944 the Eighth Area Army was directed by the General Staff to "hold the area around Rabaul for as long as possible, in cooperation with the Imperial Japanese Navy".[16] Until mid-1944 the Eighth Area Army believed that the Allies would conduct a major assault on Rabaul. After this time, they judged that the Allies were more likely to gradually expand their control over New Britain and only attack the town if their campaign towards Japan became bogged down or concluded, or if the size of Australian forces on the island was increased.[17]

In late April 1944, the US Army's 40th Infantry Division assumed responsibility for garrisoning the Allied positions in New Britain,[18][14] moving from Guadalcanal.[19] The use of an Australian formation to relieve the Marines had been considered at this time, but due to a lack of suitable shipping and equipment interoperability issues, the decision was made to temporarily defer this.[20] The 40th Infantry Division subsequently maintained positions around Talasea–Cape Hoskins, Arawe and Cape Gloucester and did not conduct offensive operations against the Japanese forces in the east of the island.[21] As a result, the fighting on New Britain devolved largely into what historian Peter Dennis has called a "tacit truce" with the US and Japanese troops being separated by a "no man's land", in which Australian-led native troops from the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) conducted a small-scale guerilla campaign.[21]

In mid-1944, the Australian Government agreed to take on responsibility for military operations in the British and Australian territories and mandates in the South-West Pacific, including Australian New Guinea, of which New Britain was part, and the northern Solomon Islands. US troops were reallocated for operations to secure the Philippines.[22] In August, the Australian Army's 5th Division, under Major General Alan Ramsay, was selected to replace the 40th Infantry Division on New Britain. The formation was to assume responsibility for the island on 1 November.[23] Instead of maintaining the American bases in western New Britain the Australians planned to operate closer to the Japanese forces around the Gazelle Peninsula.[21] By the time of the Australian take over, Allied intelligence estimated that the Japanese forces on New Britain amounted to 38,000 personnel, but in actuality there were 93,000 Japanese on the island.[14][24] The Japanese personnel were focused upon sustaining themselves, with rice-growing and gardening being undertaken to supplement the limited supplies that were arriving. Naval and air support for the force was limited, with only two aircraft capable of action and no ships other than 150 barges that could move up to 90 personnel or 15 tons of stores.[21]

As of April 1944, small Japanese observation posts were located along the south coast of New Britain as far west as the village of Awul, near Cape Dampier, approximately 100 miles (160 km) east of Arawe. There was an observation post at Jacquinot Bay. A larger force was stationed at Henry Reid Bay in the Wide Bay area.[15][25] During that month the AIB force responsible for the south coast of New Britain was ordered to destroy all the Japanese posts to the west of Henry Reid Bay. This unit comprised about 140 native troops led by five Australian officers and ten Australian non-commissioned officers.[26]

Preliminary operations

In mid-April, the coastwatching station at Jacquinot Bay was the first Japanese position to be attacked. A platoon of native troops led by two Australians attacked it after learning that it was lightly defended. Five of the ten IJN personnel stationed there were killed in the initial attack, and four of the survivors were hunted down and killed. The other Japanese sailor was taken prisoner. Two other Japanese sailors were taken prisoner in the Jacquinot Bay region on 22 April after the native troops attacked a barge. The three prisoners were evacuated by an American PT boat later that month. The IJN command responsible for New Britain was never able to determine the fate of the Jacquinot Bay garrison or the barge.[27]

Broader operations against the Japanese observation posts began in June. On the fifth of the month a patrol of American troops attacked the position at Awul, causing its garrison to retreat into the centre of the island. Other attacks by the AIB force followed, and by early September all of the Japanese observation posts west of Wide Bay had been destroyed. Japanese troops conducted small-scale reprisals against the native population of the Wide Bay hinterland, and the AIB officers attempted to persuade the population of this area to move inland before more severe reprisals were conducted.[28]

During the operations along the south coast of New Britain, the AIB officers sought to discourage the Japanese from moving west of the Wide Bay area by circulating rumours among the local population that a large Australian base had been established at Jacquinot Bay. In reality no such base existed at this time.[29] The AIB force continued to make guerilla attacks on Japanese positions until early October, when it was ordered to cease offensive operations and concentrate on intelligence gathering ahead of the Australian landing at Jacquinot Bay.[30] The AIB's operations from June to October were assisted on occasion by Allied air attacks and naval bombardments.[31]

Preparations

To support the 5th Division's planned offensive operations the Australian high command in the New Guinea area, New Guinea Force, determined that a logistics base needed to be established closer to Rabaul than those used by the US Army forces on New Britain.[20] At a conference held on 24 August involving the commanders of New Guinea Force and the 5th Division, it was decided to investigate whether the Talasea–Hoskins area on the north coast of New Britain and the Jacquinot Bay area on the south coast of the island could accommodate bases for the 5th Division.[32] The 5th Division had previously been deployed to New Guinea in 1943–1944, but had been reorganised for operations on New Britain. By the time of its commitment it consisted of three infantry brigades: the 4th, 6th and 13th.[33]

On 5 September, a party of 105 personnel from the 5th Division, 2/8th Commando Squadron, New Guinea Force and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was landed at Jacquinot Bay from the corvette HMAS Kiama.[34][35] Assisted by AIB personnel, they investigated the area for two days while Kiama surveyed the bay.[34] It was concluded that the region was suitable for a base as the bay could accommodate up to six liberty ships in all weather, a wharf capable of handling these vessels could be constructed relatively easily, room was available ashore to accommodate the 5th Division's base installations and combat formations, and an airstrip could be built nearby.[36][37] M Special Unit also reported that no Japanese personnel remained in the Jacquinot Bay area.[38] The party which visited the Talasea–Hoskins area (already housing an American base) made a less favourable report. In particular, the report noted that the area lacked anchorages which were fully protected from the weather and it would not be possible to build a wharf capable of accommodating Liberty ships at either Talasea or Hoskins.[36][39] On 15 September, the commander of the Australian Army's combat forces, General Thomas Blamey, approved a proposal to establish a base at Jacquinot Bay. He also agreed for two battalions of the 6th Brigade to be landed at Jacquinot Bay, with the formation's third battalion being sent to Talasea–Hoskins.[32]

At this time the 6th Brigade – consisting of the 19th, 36th and 14th/32nd Battalions – was led by Brigadier Raymond Sandover. A Militia formation, it had not previously seen combat as a whole, though one of its infantry battalions (the 36th) had fought in the Battle of Buna–Gona during late 1942 and early 1943. Nevertheless, Sandover and his three battalion commanders – Lieutenant Colonels Lindsay Miell (19th), Oscar Isaachsen (36th), and William Caldwell (14th/32nd) – were all Australian Imperial Force veterans who had taken part in the fighting against the Germans and Italians in North Africa and Greece, and the Vichy French in Syria during 1941 and 1942.[40] The 36th Battalion was dispatched to Cape Hoskins from Lae, in early October,[38] and relieved a battalion of the US 185th Infantry Regiment.[40]

The RAAF conducted three attacks on Rabaul as part of the preparations for the landing at Jacquinot Bay. On the night of 26 October a force of 18 Bristol Beaufort light bombers drawn from Nos. 6, 8 and 100 Squadrons attacked Japanese stores dumps and anti-aircraft positions at Rabaul. The results of this mission were unclear. The next raid by the three squadrons was conducted against stores dumps to the north of Rabaul on the evening of 27 October, with most of the bombs dropped landing in the target area. The third raid took place on 29 October, and involved 20 Beauforts from the three squadrons striking stores dumps to the west of Rabaul.[41]

Landing

While AIB patrols continued to report that no Japanese troops were located in the Jacquinot Bay area, the Australian command decided that the landing there would be made by a combat-ready force protected by naval vessels. This was intended both as a precaution against a sudden Japanese offensive and to provide useful experience for the units involved.[42] The landing was designated Operation Battleaxe.[43]

The 14th/32nd Battalion Group was assigned as the initial landing force. The battalion had been raised in the state of Victoria during 1942, and was still mainly made up of Victorian soldiers.[40] It was supplemented by B Company of the 1st New Guinea Infantry Battalion (1 NGIB).[44] An advance party from the 5th Base Sub Area was also deployed. The Australian troops embarked on the transport Cape Alexander at Lae on 2 November.[45] The transport sailed that afternoon under the escort of three Royal Australian Navy (RAN) warships: the destroyer Vendetta, the frigate Barcoo and sloop Swan. The New Guinean soldiers were allocated to the former ferry Frances Peat, which was escorted from Lae to Jacquinot Bay by RAN motor launch ML 827. In addition to the ships which departed from Lae, another convoy of small craft proceeded to Jacquinot Bay from Arawe. This force comprised B Company of the US Army's 594th Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, the tugboat HMAS Tancred and ML 802 which served as an escort. The American unit operated 14 Landing Craft Mechanized (LCMs) and 9 Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVPs). Tancred was towing a workshop barge.[42][46][47]

Elements of the RAAF were also available to support the landing. The plan for the operation specified that, if required, No. 6 Squadron, reinforced with Beauforts from Nos. 8 and 100 Squadrons, would attack the landing area before 6 am on 4 November. An additional two Beauforts could also observe for any bombardments made by the warships.[48] Prior to the landing, the air strike was cancelled by the RAAF officer who was attached to the landing force to coordinate air support as no opposition was expected.[48]

Cape Alexander and her escorts arrived at Jacquinot Bay at 6:35 am on 4 November, and were joined by the other Allied vessels shortly thereafter. While the voyage from Lae had been uneventful, the 14th/32nd Battalion's war diary records that the unit's accommodation on board the transport had been "very poor" as it was "very cramped, dirty and wet" and sanitary facilities were greatly insufficient.[43][45] The landing of the 14th/32nd Battalion commenced at 9:30 am, with A Company making up the first wave. All elements of the battalion were ashore by 11:30 am.[49] No opposition was encountered, and the 14th/32nd Battalion began to establish defensive and living positions. In addition, personnel from the battalion were detailed to unload stores.[42][49] Patrols were also sent out towards Wunung and Palmal, while a reconnaissance party from headquarters 5th Division was sent to the mission at Mal Mal.[50] Sandover regarded the lack of opposition as fortunate, as the landing craft which were to carry the soldiers from the ships to the shore arrived late and he perceived that the RAAF had failed to provide adequate support. However, he was pleased with his brigade's performance during operations in New Britain up to that time, and expressed pleasure at having "nearly reached the war".[42]

The following day, bad weather affected further landing operations around the bay. The beach around Mal Mal was usable and the nearby road found to be suitable for jeeps; however, the beachhead around Wunung was found to be unsatisfactory. Operations ceased at Kamalgaman and the landing of the 1 NGIB troops around Pomio had to be delayed.[51] Despite the weather, the 180 man-strong advance party of the 5th Base Sub Area was landed on 5 November, and began work on establishing logistics facilities.[52]

After covering the landing force for two days, Vendetta, Barcoo and Swan proceeded to Wide Bay and bombarded Japanese positions there before departing the New Britain area. The motor launches ML 802 and ML 827 remained at Jacquinot Bay and conducted patrols along the south coast of the island in search of Japanese barges.[42] ML 827 ran aground during a patrol on 17 November, and sank three days later while under tow to an Allied base. All of her crew survived.[53] A Japanese air raid was conducted against Jacquinot Bay on 23 November.[54]

In the days after the landing, ground forces secured the Jacquinot Bay area. AIB personnel manned an outpost to warn of approaching Japanese forces, while the combat troops patrolled and established positions near the main landing area. On 6 November, the company from 1 NGIB was moved by landing craft to the northern shore of Jacquinot Bay, at Pomio, after the jetty there was rebuilt.[55] They subsequently guarded tracks leading to this area. The unit later relieved the AIB of responsibility for maintaining some of its positions to the east of Jacquinot Bay. The 14th/32nd Battalion remained near the landing area; though, between 8 and 12 November, one of its companies gradually established an outpost.[56]

Aftermath

Base construction

Rudimentary base construction began as soon as the advance party of the base sub area arrived on 5 November. Bulldozers were used to clear the ground for tents to be set up for support personnel, and tracks were established around the site. The unloading of stores was hampered by rain, which began to fall shortly after the landing and continued throughout the first week. Initially, stores were offloaded onto the beach and then carried by hand further ashore. A pontoon jetty with rollers was constructed. By the time the remainder of the 5th Base Sub Area arrived on 11 and 12 November, 4,400 cubic yards (3,400 m3) of stores and equipment had been unloaded. These troops arrived aboard the transports J. Sterling Moreton and Swartenhondt, with a party of 670 native labourers.[52] Major base construction works began on the second week after the landing. Kitchens, messes, a bakery, a sawmill, recreational facilities, latrines and other buildings were then established, although the completion of some buildings was delayed by shortages of engineer stores. The 2/3rd Railway Construction Company landed on 21 November, and worked on building roads. By 24 November, the road along the beach and several minor roads had been completed but use of these was restricted to dry periods. The headquarters of the 5th Division opened at Jacquinot Bay on 27 November.[54]

Assisted by a period of good weather, work on major facilities at Jacquinot Bay began in December. These included: a large dock, an airstrip, stores depots and buildings to be used by 2/8th General Hospital. Sufficient stores were to be stockpiled to support 13,000 soldiers for 60 days. After ten days of dry weather in January 1945, the water reservoirs at Jacquinot Bay ran dry. Wells were dug but the water found was not potable. Water restrictions were imposed, and LCMs shipped water to Jacquinot Bay for three days.[57] The airstrip was completed in May 1945.[58] Originally, No. 79 Wing RAAF was to operate from Jacquinot Bay but it was reassigned to support Australian operations in Borneo. It was replaced by units of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Two squadrons of Corsair fighter aircraft, a squadron operating Ventura maritime patrol aircraft and several support units were based at Jacquinot Bay from May 1945 until after the end of the war.[59]

The 6th Brigade (less the 36th Battalion deployed at Cape Hoskins), was gradually brought into the Jacquinot Bay area, with its final elements arriving on 16 December 1944.[60] Due to shipping shortages and the low priority given to building up forces on New Britain, it was not until April 1945 that all elements of the 5th Division had been brought forward to Jacquinot Bay,[57] with the remaining combat elements (the 4th and 13th Brigades, the 2/14th Field Regiment and the 2/2nd Commando Squadron) deploying from Darwin, Lae and Madang throughout this period.[61] The company from the 594th Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment remained at Jacquinot Bay and was solely responsible for port operations until the 41st Australian Landing Craft Company arrived on 15 February 1945,[42] deploying from Cairns. The 41st was equipped with smaller, less robust craft than the US unit, but further development of the port facilities to accommodate a wharf for unloading Liberty ships, and continuing improvement of the roads and bridges ashore, allowed the US company and its LCMs to be withdrawn by mid-April 1945.[62]

Subsequent operations

As Allied intelligence regarding the Japanese was still uncertain – with information being at times either incomplete, conflicting, or even incorrect – Ramsay, who officially assumed command of the forces on New Britain on 27 November, adopted a cautious approach. Jacquinot Bay was built up as a base of operations and the Australians began sending out patrols to fight for information and harass the Japanese, with limited advances taking place on both the northern and southern coasts of the island, pushing east towards the Japanese strong hold around the Gazelle Peninsula.[21] The AIB, with a base at Jacquinot Bay, also continued to operate behind Japanese lines and passed information to the 5th Division.[21][63] The Japanese lacked information on the movements of Allied forces in New Britain, and only learned of the change in command from Australian radio broadcasts.[64] They subsequently maintained a largely defensive posture, focusing upon maintaining the garrison around Rabaul.[21][65] Australian official historian Gavin Long wrote that it was unclear why the Japanese stance on New Britain was so passive when the Australian offensive on Bougainville was strongly resisted.[66]

Although few Japanese troops contested the Australian advance, it was hampered by shortages of shipping and aircraft. As a result, operations were limited to brigade-strength only. Until the airstrip was completed, air support was provided by aircraft based in New Guinea, meaning that there was a delay of around a day for support requests. There was also a shortage of light and reconnaissance aircraft.[21]

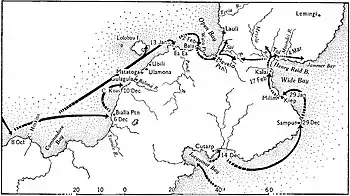

In January 1945, the 36th Battalion was dispatched from Cape Hoskins to Ea Ea on the north coast of New Britain by barge, and began sending out company-sized patrols. They subsequently reached Watu Point, in Open Bay, at the base of the Gazelle Peninsula by April. Relief of the 36th Battalion was delayed by a shortage of shipping.[67] Its replacement, the 37th/52nd Battalion, had to march overland rather than move by sea. The Australian forces also advanced along the south coast of the island, and began securing the Waitavalo–Tol area (Henry Reid Bay) in late February. Engineer support enabled crossing of the Wulwut River. Several clashes followed around Mount Sugi as the Australians fought to gain control of heavily defended ridges overlooking Henry Reid Bay. Rain and flooding hampered their efforts. By April, the Australians had secured Wide Bay and effectively hemmed the Japanese into the Gazelle Peninsula and contain them for the remainder of the campaign. This enabled the Allies to focus their attention elsewhere, such as Borneo.[21][65]

Citations

- Long (1963), Map p. 243

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), p. 1

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), pp. 4, 8–9, 16 & 27

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), p. 16

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), p. 34

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), pp. 30–40

- Allied Geographical Section (1943), pp. 1 & 31

- Horner, David. "Strategy and Command in Australia's New Guinea Campaigns". Remembering the war in New Guinea. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Drea (1993), pp. 16–17

- Dexter (1961), p. 787

- Keogh (1965), pp. 360–361

- Keogh (1965), pp. 415–416

- Shindo (2016), pp. 53–59

- Grant (2016), p. 225

- Powell (1996), p. 245

- Shindo (2016), p. 59

- Long (1963), pp. 266–267

- Hough and Crown (1952), p. 207

- Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 429

- Mallett (2007), p. 286

- Dennis et al (2008), p. 390

- Keogh (1965), p. 396

- Long (1973), p. 405

- Long (1963), p. 241

- Long (1963), pp. 242–243

- Long (1963), pp. 242–244

- Powell (1996), pp. 246–247

- Long (1963), pp. 244–245

- Long (1963), p. 245

- Long (1963), pp. 245–246

- Gill (1968), p. 490

- Long (1963), p. 248

- McKenzie-Smith (2018), pp. 2,036–2,037

- Gill (1968), p. 491

- "2/8th Independent Company". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Long (1963), pp. 245, 248–249

- 5th Division (1945), pp. 16–17

- Mallett (2007), p. 287

- 5th Division (1945), p. 17

- Long (1963), p. 249

- Odgers (1968), p. 330

- Long (1963), p. 250

- Gill (1968), p. 492

- McKenzie-Smith (2018), p. 2,267

- 14th/32nd Infantry Battalion (1944), p. 104

- Mallett 2007, pp. 22, 288 & 290

- 5th Division (1945), p. 22

- Odgers (1968), p. 329

- 14th/32nd Infantry Battalion (1944), p. 105

- 5th Division (1944), p. 17

- 5th Division (1944), p. 37

- Mallett (2007), p. 288

- Gill (1968), p. 493

- Mallett (2007), p. 289

- 5th Division (1944), p. 47

- 5th Division (1945), p. 35

- Mallett (2007), p. 290

- Bradley (2012), p. 408

- Ross (1955), p. 309

- Long (1963), p. 252

- Long (1963), p. 251

- Mallett 2007, p. 292

- Powell (1996), p. 251

- Charlton (1983), p. 95

- Grant (2016), p. 226

- Long (1963), p. 269

- Long (1963), p. 260

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Landing at Jacquinot Bay. |

- 5th Division (1944). "November 1944, part 1, Unit diary". 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and CMF (Citizen Military Forces) unit war diaries, 1939–45 War. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 16 December 2018. (Page numbers cited are those of the PDF document on the AWM website)

- 5th Division (1945). "October 1944 – April 1945, Report on operations". 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and CMF (Citizen Military Forces) unit war diaries, 1939–45 War. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- 14th/32nd Infantry Battalion (1944). "AWM52 8/3/53/10: October – December 1944". 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and CMF (Citizen Military Forces) unit war diaries, 1939–45 War. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area (1943). Terrain Study No. 51: Area Study of Eastern New Britain Excluding the Gazelle Peninsula. Brisbane, Queensland. OCLC 220852766 – via Monash Collections Online.

- Bradley, Phillip (2012). Hell's Battlefield: The Australians in New Guinea in World War II. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1742372709.

- Charlton, Peter (1983). The Unnecessary War: Island Campaigns of the South-West Pacific, 1944–45. South Melbourne: Macmillan Company of Australia. ISBN 978-0333356289.

- Dennis, Peter; et al. (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195517842.

- Dexter, David (1961). The New Guinea Offensives. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Volume VI. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2028994.

- Drea, Edward J. (1993). New Guinea. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. Washington DC: US Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0160380990.

- Gill, G Hermon (1968). Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume II. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 65475.

- Grant, Lachlan (2016). "Given a Second Rate Job: Campaigns in Aitape–Wewak and New Britain, 1944–45". In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–231. ISBN 978-1107083462.

- Hough, Frank O.; Crown, John A. (1952). The Campaign on New Britain. USMC Historical Monograph. Washington DC: Historical Division, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 1283735.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Productions. OCLC 7185705.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Volume VII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1297619.

- Long, Gavin (1973). The Six Years War. A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–1945 War. Canberra: Australian War Memorial and Australian Government Printing Service. ISBN 978-0642993755.

- Mallett, Ross A. (2007). "Australian Army Logistics 1943–1945". Ph.D. thesis. University of New South Wales. OCLC 271462761. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- McKenzie-Smith, Graham (2018). The Unit Guide: The Australian Army 1939–1945, Volume 2. Warriewood, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1925675146.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Air War Against Japan, 1943–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume II. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1990609.

- Powell, Alan (1996). War by Stealth: Australians and the Allied Intelligence Bureau, 1942–1945. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0522846911.

- Ross, J.M.S. (1955). Royal New Zealand Air Force. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs. OCLC 173284660.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Isolation of Rabaul. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. II. Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 987396568.

- Shindo, Hiroyuki (2016). "Holding on to the Finish: The Japanese Army in the South and South West Pacific 1944–45". In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–76. ISBN 978-1-107-08346-2.