Land Rush of 1889

The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 was the first land run into the Unassigned Lands. The area that was opened to settlement included all or part of the Canadian, Cleveland, Kingfisher, Logan, Oklahoma, and Payne counties of the US state of Oklahoma.[1] The land run started at high noon on April 22, 1889, with an estimated 50,000 people lined up for their piece of the available two million acres (8,000 km2).[2]

A land rush in progress | |

| Date | April 22, 1889 |

|---|---|

| Location | Central Oklahoma |

| Also known as | Oklahoma Land Rush |

The Unassigned Lands were considered some of the best unoccupied public land in the United States. The Indian Appropriations Act of 1889 was passed and signed into law with an amendment by Illinois Representative William McKendree Springer that authorized President Benjamin Harrison to open the two million acres (8,000 km²) for settlement. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act of 1862 which allowed settlers to claim lots of up to 160 acres (0.65 km2), provided that they lived on the land and improved it.[2]

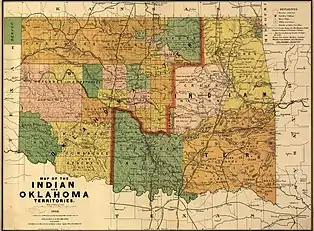

Native American tribes in Indian Territory

The removal of Native Americans to Indian Territory started after the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828. The federal government was unwilling to help the tribes in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi fight against state laws passed against them. President Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act on May 28, 1830.

Choctaw

The Choctaws were the first tribe to concede to removal in 1830. They agreed to give up their land and move to the designated Indian Territory.[3] The main portions of the Choctaw tribe moved to Indian Territory from 1830–1833, with the promise that they would be granted autonomy. Many perished on the journey to the new territory.

Creek

The Creeks were the next tribe to move to Indian Territory. In 1829 a council was held and it was agreed that they would submit to state laws and stay on their lands. However, pressure from settlers and the state government lead to the Creek Tribe surrendering its lands to the state of Alabama.[4] By 1836, the entire Creek Tribe had been removed to Oklahoma after the killing and pillaging of white settlers and a civil war within the tribe.[5]

Cherokee

The Cherokees were the third tribe to be removed to Indian Territory. Tribal leaders Chief John Ross, and other high ranking families did the most they could to keep their lands. Jackson actively refused to enforce the ruling in the Worcester v. Georgia case, ruling that the Cherokee Nation was a community that had its own boundaries and the citizens of Georgia could not enter their lands without consent of the Cherokee Tribe.[4] The necessity to leave Georgia to Oklahoma became inevitable to Chief John Ross. Eventually the U.S. military came and forced the removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory. By the end of 1838, the Cherokee tribe had been fully removed to Oklahoma. Out of the 18,000 that made the trip from 1835 to 1838, about 4,000 perished.[6]

Chickasaw

The Chickasaws elected to leave their lands freely and did not suffer like the Cherokee tribe. The tribe was progressing by frontier standards in that they were educating children, building churches, and farming. They were faced with the problem of the federal government not being able to protect them from the state government of Mississippi. Beginning in 1832 a collection of treaties were signed, granting them better terms than the other tribes had received. They left for Oklahoma in the winter of 1837–38 and paid the Choctaws to be able to settle on their lands.[7]

Seminole

The Seminole Tribe was tricked into signing a removal treaty and the Seminole War is what followed. This was the bloodiest and costliest Indian war in United States history. Chief Osceola and his tribe hid in the Everglades in Florida, and the military sought to hunt them down. Many were captured and sent to Oklahoma in chains. Osceola surrendered and died in prison. The war and removal reduced their population by 40%, and only 2,254 were left in 1859 according to the 1859 census.[8]

Plains Tribes in the Territory

After the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes, they were later joined by tribes of the plains who were forced into the territory after wars with the U.S. military. The Quapaws and Senecas were placed in Northeast Oklahoma with the Cherokees.[9] They were later joined by the Shawnees, Delawares, and Kickapoos by 1845. After the entrance of Texas into the Union, the Caddos, Kiowas, and parts of the Comanche tribe were placed in Indian Territory after treaties with the Civilized Tribes. By 1880, the Wyandots, Cheyennes, Arapahos, Wichitas, and other smaller tribes had been removed from surrounding states and placed into Oklahoma.

Start of the Boomer Movement

Americans at this time were facing the troubles of land overpopulation in the east where millions of people were occupying only thousands of square miles of land. The Civil War had also just ended, sparking people's interest in occupying the west. The only problem was the Indian Territory was not open to settlers at this crucial time. Americans called for their legislators to open the Indian Territory and certain Native Americans like Elias C. Boudinot encouraged other Native Americans to participate in the effort to welcome westward expansion.[10] As a result, thirty-three bills were presented before congress introducing legislation to open the territory for settlement in the course of ten years from 1870 to 1879.[11]

Legislation was passed through Congress in 1866 that permitted railroads to be laid in sections of 40 miles (64 km) on either sides of the Indian Territory. The two companies in charge of creating these railroads were the Atlantic and the Pacific, although their contracts were eventually rescinded due to not finishing the projects in the agreed time. Railroad companies that came up after them took it as their responsibility to finish the project, and saw a way to strengthen their contracts by introducing the movement of white settlement in the Indian Territory.[12] The Railroads employed people like C. C. Carpenter to spread false information in newspapers of the Indian Territory being open to settlement through Congress's Homestead laws. The articles were a success as a large movement of black and white settlers began to move to the Oklahoma Territory. The President of that time, Rutherford B. Hayes, issued warnings to the boomers to not move into the Indian land, and issued commands to the military to use force to ensure this.[12]

Boomers and Sooners

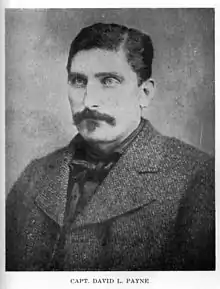

A number of the people who participated in the run entered the unoccupied land early and hid there until the legal time of entry to lay quick claim to some of the most choice homesteads. These people came to be identified as "Sooners". This led to hundreds of legal contests that arose and were decided first at local land offices and eventually by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Arguments included what constituted the "legal time of entry".[13] While some people think that the settlers who entered the territory at the legally appointed time were known as "boomers", the term actually refers to those who campaigned for the opening of the lands, led by David L. Payne.[14]

The University of Oklahoma's fight song, "Boomer Sooner", derives from these two names.[15]The school "mascot" is a replica of a 19th-century covered wagon, called the "Sooner Schooner." When the OU football team scores, the Sooner Schooner is pulled across the field by a pair of ponies named "Boomer" and "Sooner.” There are a pair of costumed mascots also named "Boomer" and "Sooner" as well.

David Payne

Captain David L. Payne grabbed hold of this booming movement to occupy and create the Oklahoma Territory. He and other enthusiasts created the Oklahoma Colony, allowing settlers to join with the fee of a minimum of one dollar. Then once settled in the Oklahoma Territory they organized themselves as a town-site company that sold lots of land from a range of $2–25 depending on the demand of the Boomer Movement.[12] Cattlemen, afraid that these boomers would take their land, worked to keep them out alongside the military. Settlers thought it their right to occupy the lands as they had purchased it with cash and by doing so, their title was invested in the U.S. government.[16] Even so, the military was at constant work to arrest the boomers unlawfully on Indian Territory, although they were generally released without having to go on trial.

On November 28, 1884, Captain David L. Payne met his end at a hotel in Kansas due to poison found in his glass of milk. It is speculated that it was organized by cattlemen unhappy with the success of the Boomer Movement.[16]

William Couch

William Couch was a former lieutenant under Payne. He did not possess the brash personality of his predecessor; however, he had a kindred personality and spoke with strength. He rigorously studied all treaties, court cases, and laws regarding the Oklahoma land issue in order to present logical and concise boomer claims.[17] He had led unsuccessful movements into Indian Territory, but under military and legal pressure the Oklahoma movement stagnated. It was rebooted with the construction of the Santa Fe Railroad line across the middle of Indian Territory from Arkansas City, Kansas to Gainesville, Texas.[18] Certain that the lands would be opened to settlement shortly after the construction of the railroad was completed in the spring of 1887, the Oklahoma movement again slowed down.

By December 1887 the inaction of Congress reignited the movement behind the leadership of William Couch. After a conference of boomers was held in Kansas, the conference sent delegates Sydney Clarke, Samuel Crocker, and William Couch to Washington to promote the passage of an act to open Oklahoma lands for settlement.[19] After Couch and company presented the bill to Congress, it faced opposition from state representatives George T. Barnes of Georgia, Charles E. Hooker of Mississippi, and Colonel G.W. Harkins of the Chickasaw Nation.[20] They opposed it based on the premise that the U.S. government had promised the land to the Indian Nations living there and the government did not have the right to open up land in the territory to settlement.

The Springer Oklahoma Bill, which was proposed by Illinois representative William M. Springer, was meant to use the Homestead Act to open the lands for settlement.[21] Arguments over the payment for the lands went up until the legislative session ended and the bill was not passed. In December, Couch presented the Springer Oklahoma Bill to Congress again, which led to the passage of the Indian Appropriation Bill.[22] With this bill, Congress paid $1,912,952.02 to the Seminole and Creek Nations in exchange for 2,370,414.62 acres of unassigned land. A section giving the president the authority to open the land to white settlement was added.[22]

African-Americans

African Americans had been trying to find communities they could settle without the worries of racism against them. During the time that the Land Rush took place, black families were building their own way of life and culture since the Reconstruction era. Even in the Oklahoma Territory, the five main Native American Tribes had to sign agreements with the US government that they would no longer practice slavery, and if they continued, they would be exempted from their land by the United States.[23]

During the Land Rush, it was a growing belief within the African American community that this opening of free land was their opportunity to create communities of their very own, without the influence of racism. Their intentions were to make Oklahoma a state just for them. One organization that took advantage of this movement was the Oklahoma Immigration Organization owned by W. L. Eagleson. Eagleson spread the announcement of recolonization to the black community throughout the United States, especially focused in the South.[24]

_LCCN2014682280.jpg.webp)

One attempt to make Oklahoma a black state was to appoint Edward Preston McCabe as the Governor of the Oklahoma Territory. This would make it easier for black families to settle within the region during the land rush. This plan fell through the cracks, as there seemed to be less and less excitement of immigrating to the new land, and instead McCabe had to settle to being a treasurer in Logan County of Oklahoma.[24]

The attempts of people like Eagleson and McCabe were not completely futile as their support of the black family did enthuse many to continue to move to the Oklahoma Territory. These movements did become townships, such as Kingfisher.[24]

Rush for land

_LCCN2014682281.tif.jpg.webp)

After the passage of the Indian Appropriation Bill, President Benjamin Harrison made the declaration that on April 22, 1889, at 12 o'clock noon that the Unassigned Land in Indian Territory would be open for settlement.[25] At the time of the opening, which was indicated by gunshot, the line of people on horse and in wagons dispersed into a kaleidoscope of motion and dust and oxen and wagons. The chase for land was frenzied and much chaos and disorder ensued. The rush did not last long, and by the end of the day nearly two million acres of land had been claimed. By the end of the year, 62,000 settlers lived in the Unassigned Lands located between the Five Tribes on the east and the Plains Tribes on the west.[26]

Rapid growth

By the end of the day (April 22, 1889), both Oklahoma City and Guthrie had established cities of around 10,000 people in literally half a day. As Harper's Weekly put it:

At twelve o'clock on Monday, April 22d, the resident population of Guthrie was nothing; before sundown it was at least ten thousand. In that time streets had been laid out, town lots staked off, and steps taken toward the formation of a municipal government.[27]

Many settlers immediately started improving their new land or stood in line waiting to file their claim. Many children sold creek water to homesteaders waiting in line for five cents a cup, while other children gathered buffalo dung to provide fuel for cooking.[28] By the second week, schools had opened and were being taught by volunteers paid by pupils' parents until regular school districts could be established. Within one month, Oklahoma City had five banks and six newspapers.[28]

On May 2, 1890, the Oklahoma Organic Act was passed creating the Oklahoma Territory. This act included the Panhandle of Oklahoma within the territory. It also allowed for central governments and designated Guthrie as the territory's capital.[29]

Expansion of cities

With the signal of troops to cross into the territory, over a dozen Santa Fe trains pulled into Oklahoma Territory, and most others traveled by other means—on horseback, in wagons, and on foot. Establishing a claim involved placing a stake with the claimant's name and place of entry at a U.S. land, one of which was located in Guthrie and the other in Kingfisher.[30] The settler had to live on the claimed section of land for a five-year period before they could attain the title to the property. That period could be shortened to fourteen months if the settler paid a price of $1.25 per acre.

Guthrie, Oklahoma City, Kingfisher, El Reno, Norman, and Stillwater were six of the townsites established in 1889 and they were given county seats.[31] Guthrie was named capital of the Territory and later was capital of the state of Oklahoma for a brief period. Oklahoma City then became the permanent capital of the state. On April 23, Oklahoma City contained more than 12,000 people. Within an hour of land being opened, 2,500 settlers occupied lands in their township that they initially named Lisbon, but would later be called Kingfisher.[32]

In popular culture

- Hollywood has produced motion pictures illustrating the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889 and the way of a pioneer's life on the acreaged claims. Two of these, both named Cimarron, were based upon the 1929 novel of the same name by Edna Ferber:

- Cimarron (1931): directed by Wesley Ruggles; screenplay cast includes Richard Dix, Irene Dunne, and Estelle Taylor. It was an Academy Award Winner for Best Art Direction, Best Picture, Best Writing and Adaptation.[33]

- Cimarron (1960): directed by Anthony Mann and Charles Walters; screenplay cast includes Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, and Anne Baxter.[34]

- The Oklahoma City 89ers was the original name for the Oklahoma City Triple-A Minor League Baseball from 1962 to 1997, when the team played at the now-demolished All Sports Stadium at the state fairgrounds. The team is currently known as the Oklahoma City Dodgers. Among the most notable players for the 89ers were Juan González, National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Ryne Sandberg, Rubén Sierra and Sammy Sosa.

- The 1992 film Far and Away, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, depicts a young Irish couple fleeing to the States with hopes of participating in the Oklahoma Run and staking claim to their own land.

- The Rush is also the central theme of the comic album Ruée sur l'Oklahoma, the 14th album of the Belgian comics series Lucky Luke.[35]

See also

- Nannita Daisey, who said she was the first woman laying a claim on Oklahoma land

- Boomers (Oklahoma settlers)

References

- "Rushes to Statehood, The Oklahoma Land Runs". Dickinson Research Center. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- "1890 Oklahoma Territory Census". Archived from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 101.

- Foreman, Grant (2018). The Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 102.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman,OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 104.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 109.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 109–111.

- Debo, Angie (1979). A History of the Indians of the United States. Norman, OK: Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 112.

- Dwyer, John J. (November 9, 2015). "America's last frontier: Oklahoma: with America's westward expansion petering out, owing to a lack of available land, easterners demanded that government open up Indian territory, leading to land rushes". Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Shirley, Glenn (1990). West of Hell's Fringe: Crime, Criminals, and the Federal Peace Officer in Oklahoma Territory, 1889–1907. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 5. ISBN 0806122641.

- Buck, Solon Justus (1907). The Settlement of Oklahoma. Democrat printing Company, state printer. pp. 19–21.

- Hoig, Stan. "Land Run of 1889". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Hoig, Stan. "Boomer Movement". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- What is a Sooner. Archived June 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine SoonerAthletics. University of Oklahoma. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- "Oklahoma's Boom". The Atchison Daily Globe. March 6, 1889. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Rister, Carl (1942). Land Hunger: David L. Payne and the Oklahoma Boomers. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 189.

- Hoig, Stan (1984). Land Rush of 1889. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma. p. 4.

- Hoig, Stan (1984). Land Rush of 1889. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 6.

- Hoig, Stan (1984). Land Rush of 1889. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 7–9.

- Hoig, Stan (1984). Land Rush of 1889. Normn, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 11.

- Hightower, Michael (2018). 1889: The Boomer Movement, the Land Rush, and Early Oklahoma City. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 152.

- McReynolds, Edwin (1981). Oklahoma: a History of the Sooner State. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 232.

- Littlefield, Daniel (1962). Black Dreams and 'Free' Homes: The Oklahoma Territory, 1891–1894. Atlanta University Center.

- Hightower, Michael (2018). 1889: The Boomer Movement, the Land Rush, and Early Oklahoma City. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 154.

- Frymer, Paul (2014). "A Rush and a Push and the Land is Ours": Territorial Expansion, Land Policy, and State Formation. Cambridge University Press. p. 121.

- Howard, William Willard (May 18, 1889). "The Rush To Oklahoma". Harper's Weekly. No. 33. pp. 391–94. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- "History of the Unassigned Lands". January 2, 2007. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- "Organic Act, 1890, Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- McReynolds, Edwin (1981). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 289.

- McReynolds, Edwin (1981). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 290.

- McReynolds, Edwin (1981). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma. p. 291.

- Cimarron at AllMovie

- Cimarron at AllMovie

- OCLC 435734017

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Land Run of 1889. |