Labrador duck

The Labrador duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius) was a North American bird; it has the distinction of being the first endemic North American bird species to become extinct after the Columbian Exchange, with the last known sighting occurring in 1878 in Elmira, New York.[2] It was already a rare duck before European settlers arrived, and as a result of its rarity, information on the Labrador duck is not abundant, although some, such as its habitat, characteristics, dietary habits and reasons behind its extinction, are known. There are 55 specimens of the Labrador duck preserved in museum collections worldwide.[3]

| Labrador duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stuffed specimens, AMNH | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Subfamily: | Merginae |

| Genus: | †Camptorhynchus Bonaparte, 1838 |

| Species: | †C. labradorius |

| Binomial name | |

| †Camptorhynchus labradorius Gmelin, 1789 | |

| |

Taxonomy

The Labrador duck is considered a sea duck. A basic difference in the shape of the process of metacarpal I divides the sea ducks into two groups:

- Bucephala and the mergansers

- The eiders, scoters, Histrionicus, Clangula, and Camptorhynchus

The position of the nutrient foramen of the tarsometatarsus also separates the two groups of sea ducks. In the first group, the foramen is lateral to the long axis of the lateral groove of the hypotarsus; in the second, the foramen is on or medial to the axis of that groove.[4]

The Labrador duck was also known as the pied duck and skunk duck, the former being a vernacular name that it shared with the surf scoter and the common goldeneye (and even the American oystercatcher), a fact that has led to difficulties in interpreting old records of these species. Both names refer to the male's striking white/black piebald colouration. Yet another common name was sand shoal duck, referring to its habit of feeding in shallow water. The closest evolutionary relatives of the Labrador duck are apparently the scoters (Melanitta).[5]

A mitogenomic study of the placement of the Labrador duck found the species to be closely related to the Steller's eider as shown below.[6]

| Mergini |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

The female plumage was grey. Although weakly patterned, the pattern was scoter-like. The male's plumage was black and white in an eider-like pattern, but the wings were entirely white except for the primaries. The trachea of the male was scoter-like. An expansion of the tracheal tube occurred at the anterior end, and two enlargements (as opposed to one enlargement as seen in scoters) were near the middle of the tube. The bulla was bony and round, puffing out from the left side. This asymmetrical and osseus bulla was unlike that of scoters; this bulla was similar to eiders and harlequin duck's bullae. The Labrador duck has been considered the most enigmatic of all North American birds.[7]

The Labrador duck had an oblong head with small, beady eyes. Its bill was almost as long as its head. The body was short and depressed with short, strong feet that were far behind the body. The feathers were small and the tail was short and rounded. The Labrador duck belongs to a monotypic genus.[8]

Habitat

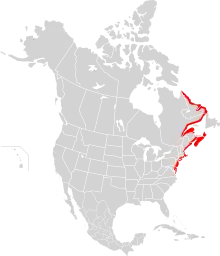

The Labrador duck migrated annually, wintering off the coasts of New Jersey and New England in the eastern United States, where it favoured southern sandy coasts, sheltered bays, harbors, and inlets, and breeding in Labrador and northern Quebec [9][10] in the summer. John James Audubon's son reported seeing a nest belonging to the species in Labrador. Some believe that it may have laid its eggs on the islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.The breeding biology of the Labrador duck is largely unknown.

Diet

The Labrador duck fed on small molluscs, and some fishermen reported catching it on fishing lines baited with mussels.[9] The structure of the bill was highly modified from that of most ducks, having a wide, flattened tip with numerous lamellae inside. In this way, it is considered an ecological counterpart of the North Pacific/North Asian Steller's eider. The beak was also particularly soft and may have been used to probe through sediment for food.[9]

Another, completely unrelated, duck with similar (but even more specialized) bill morphology is the Australian pink-eared duck, which feeds largely on plankton, but also mollusks; the condition in the Labrador duck probably resembled that in the blue duck most in outward appearance. Its peculiar bill suggests it ate shellfish and crustaceans from silt and shallow water. The Labrador duck may have survived by eating snails.

Extinction

The Labrador duck is thought to have been always rare, but between 1850 and 1870, populations waned further.[9] Its extinction (sometime after 1878)[11] is still not fully explained. Although hunted for food, this duck was considered to taste bad, rotted quickly, and fetched a low price. Consequently, it was not sought much by hunters. However, the eggs may have been overharvested, and it may have been subject to depredations by the feather trade in its breeding area, as well. Another possible factor in the bird's extinction was the decline in mussels and other shellfish on which they are believed to have fed in their winter quarters, due to growth of population and industry on the Eastern Seaboard. Although all sea ducks readily feed on shallow-water molluscs, no Western Atlantic bird species seems to have been as dependent on such food as the Labrador duck.[12]

Another theory that was said to lead to their extinction was a huge increase of human influence on the coastal ecosystems in North America, causing the birds to flee their niches and find another habitat.[13][14] These ducks were the only birds whose range was limited to the American coast of the North Atlantic, so changing niches was a difficult task.[15] The Labrador duck became extinct in the late 19th century.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camptorhynchus labradorius. |

- List of extinct birds

- List of extinct animals

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Camptorhynchus labradorius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012.

- Renko, Amanda. "EXTINCT: Seeking a bird last seen in 1878". Star Gazette. Star Gazette. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Chilton, Glen. The Curse of the Labrador Duck: My Obsessive Quest to the Edge of Extinction. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009. Print.

- Zusi, Richard (1978). "The Appendicular Myology of the Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius)". The Condor. 80 (4): 407–418. doi:10.2307/1367191. JSTOR 1367191.

- Livezey, Bradley C. (1995). "Phylogeny and Evolutionary Ecology of Modern Seaducks (Anatidae: Mergini)" (PDF). Condor. 97 (1): 233–255. doi:10.2307/1368999. JSTOR 1368999.

- Janet C. Buckner; Ryan Ellingson; David A. Gold; Terry L. Jones; David K. Jacobs (2018). "Mitogenomics supports an unexpected taxonomic relationship for the extinct diving duck Chendytes lawi and definitively places the extinct Labrador Duck". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 122: 102–109. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.12.008. PMID 29247849.

- Johnsgard, Paul. "Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Mergini (Sea Ducks)". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- "Recently Extinct Animals - Species Info - Labrador Duck." Recently Extinct Animals - Species Info - Labrador Duck. N.p., 4 June 2008. Web. 22 Oct. 2014. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2014-10-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Flannery, Tim (2001). A Gap in Nature. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0871137976.

- Chilton, Glen, and Michael D. Sorenson. "Genetic Identification Of Eggs Purportedly From The Extinct Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus Labradorius)." Auk (American Ornithologists Union) 124.3 (2007): 962-968. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

- Sibley and Monroe (Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World, 1990, p. 40)

- Phillips, John C. (1922–1926): A Natural History of Ducks. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, volume 4, pp. 57–63.

- Amadon, Dean. "Migratory Birds of Relict Distribution: Some Inferences." The Auk 70.4 (1953): 461-69. JSTOR. Web. 22 Oct. 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/4081357?ref=no-x-route:956a9a013036c5b67a48060b92a78a49

- Wilson, E.O. Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources. Washington, DC: John Henry Press, 1996. Print. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=-X5OAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA139&dq=labrador+duck+extinction&ots=f1QlkA4_cq&sig=k7BgO7drcRl9YZV8DaWFDmmzyz8#v=onepage&q&f=false

- "All About Birds". Labrador Duck. Cornell University, 2007. Web. 22 Oct. 2014. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/conservation/extinctions/labrador_duck/document_view.

Further reading

- Chilton, Glen (2009): The Curse of the Labrador Duck: My Obsessive Quest to the Edge of Extinction. Simon and Schuster, ISBN 1-43910247-3.

- Cokinos, Christopher (2000): Hope is the Thing with Feathers. New York: Putnam, pp. 281–304. ISBN 1-58542-006-9

- Ducher, William (1894). "The Labrador Duck – another specimen, with additional data respecting extant specimens" (PDF). Auk. 11 (1): 4–12. doi:10.2307/4067622. JSTOR 4067622.

- Forbush, Edward Howe (1912): A History of the Game Birds, Wild-Fowl and Shore Birds of Massachusetts and Adjacent States. Boston: Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture, pp. 411–416.

- Fuller, Errol (2001): Extinct Birds, Comstock Publishing, ISBN 0-8014-3954-X, pp. 85–87.

- Madge, Steve & Burn, Hilary (1988): Waterfowl. An identification guide to the ducks, geese and swans of the world. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 265–266. ISBN 0-395-46727-6