King Kong (1976 film)

King Kong is a 1976 American monster adventure film produced by Dino De Laurentiis and directed by John Guillermin. It is a remake of the 1933 film of the same name about a giant ape that is captured and taken to New York City for exhibition. Featuring special effects by Carlo Rambaldi, it stars Jeff Bridges, Charles Grodin and Jessica Lange in her first film role.

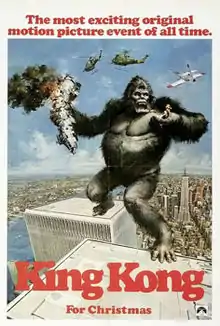

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by John Berkey | |

| Directed by | John Guillermin |

| Produced by | Dino De Laurentiis |

| Screenplay by | Lorenzo Semple Jr. |

| Based on | |

| Starring | Jeff Bridges Charles Grodin Jessica Lange |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Richard H. Kline |

| Edited by | Ralph E. Winters |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $23–24 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $74.9–90.6 million[3][2] |

The idea to remake King Kong was conceived by Michael Eisner, who was then an ABC executive, in 1974. He separately proposed the idea to Universal Pictures CEO Sidney Sheinberg and Paramount Pictures CEO Barry Diller. Dino De Laurentiis quickly acquired the film rights from RKO-General and subsequently hired television writer Lorenzo Semple, Jr. to write the script. John Guillermin was hired as director and filming lasted from January to August 1976. Before the film's release, Universal Pictures sued De Laurentiis and RKO-General alleging a breach of contract and attempted to develop their own remake of King Kong. In response, De Laurentiis and RKO-General filed separate countersuits against Universal Pictures, all of which were withdrawn by January 1976.

The film was released on December 17, 1976 to mixed reviews from film critics, but was a box office success. It won a noncompetitive Special Achievement Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, and was also nominated for Best Cinematography and Best Sound. Of the three King Kong main films, it is the only one to feature the World Trade Center instead of the Empire State Building. A sequel titled King Kong Lives was released in 1986.

Plot

Fred Wilson, an executive of the Petrox Oil Company, mounts an expedition based on infrared imagery which reveals a previously undiscovered Indian Ocean island hidden by a permanent cloud bank. Wilson believes that the island holds vast untapped deposits of oil, a potential fortune which he is determined to secure for Petrox. Unknown to Wilson or the crew, Jack Prescott, a primate paleontologist who wants to see the island for himself, has stowed away on the expedition's vessel, the Petrox Explorer. Prescott reveals himself and warns the crew that the cloud bank may be caused by animal respiration on the island. Wilson orders Prescott locked up, believing him to be a spy from a rival oil company.

While being escorted to lock-up, Prescott spots a life raft which is found to be carrying a young, unconscious woman. When she becomes conscious, she explains that her name is Dwan, and says she is an aspiring actress who was aboard a director's yacht which exploded. Wilson completes a thorough background check on the 'spy' and, having learned he is telling the truth, appoints Prescott as the expedition's official photographer.

When the Petrox Explorer arrives at the island, the team discovers a primitive tribe of natives who live with a gigantic wall separating their village from the rest of the island. The tribal chief shows an immediate interest in the blonde Dwan, offering to trade several of the native women for her, an offer firmly rejected by the shore party. Later that night, the natives secretly board the ship and kidnap Dwan, drugging her and offering her as a sacrifice to a giant, monstrous ape known as Kong. Kong encounters and frees Dwan from the stronghold before retreating into the depths of the island. Although he is an awesome and terrifying sight, the kind-hearted Kong quickly becomes infatuated by Dwan, whose panicked monologues both calms and fascinates the great ape, taming his baser, more violent instincts. After Dwan falls into mud, Kong takes her to a waterfall to wash her up and dries her with great gusts of his warm breath.

In the meantime, Jack and First Mate Carnahan lead several crew members on a rescue mission to save Dwan. The search party encounter Kong while crossing a log bridge. Enraged by the intrusion into his territory, Kong starts to roll the huge log, sending Carnahan and all but one of the team plummeting to their deaths, leaving Jack and crewman Boan as the only survivors. While Boan returns to the village to alert the others, Jack decides to keep looking for Dwan. Meanwhile, Kong takes Dwan to his mountaintop lair, but as he starts to undress her, a giant snake appears and attacks them. While Kong is distracted fighting the giant snake, Jack arrives and rescues Dwan. When Kong discovers Jack and Dwan escaping, he violently kills the snake and chases them through the jungle back to the native village. Smashing down the huge gates, Kong falls into a pit trap that Wilson and the crew have dug, where he is overwhelmed by chloroform.

The trap had been set because Wilson, having learned that the island contains minimal commercial oil, has decided to salvage the expedition by transporting the captive Kong to America as a promotional tool for Petrox. Kong is loaded in the cargo hold and transported to the United States. Along the way the great ape starts to grow increasingly distressed, and only a visit by Dwan lifts his spirits enough to enable him to survive the voyage. Dwan and Jack become upset at Kong's treatment, but when Wilson challenges them neither is willing to renounce their involvement in Wilson's promotional scheme. When they finally reach New York City, the docile Kong is put on display, bound in chains with a large cage around his body and a large crown on his head. However, when Kong sees a group of reporters surrounding Dwan for interviews and taking flash photographs of her, the ape thinks that she is being attacked and breaks free of his bonds. A stampede ensues as panic engulfs the throng, with people crushed and trampled under Kong's massive feet as he walks about searching for Dwan. Wilson, trying to flee, falls and is crushed underfoot by Kong.

Jack and Dwan flee across the Queensboro Bridge to Manhattan and take refuge in an abandoned bar, where Jack notices a similarity between the Manhattan skyline (notably the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center) and the mountainous terrain of Kong's island. He runs downstairs to call the mayor's office and agrees to tell them on the condition that Kong is captured alive. When the mayor's office agrees, Jack tells them to let Kong climb to the top of the World Trade Center, where he can be safely captured. Before Jack can return, Kong, using his enhanced senses, discovers Dwan and snatches her from the bar before making his way to the World Trade Center with Jack and the National Guard catching up in pursuit.

Kong climbs to the roof of the South Tower of the World Trade Center, where he is attacked by soldiers armed with flamethrowers, much to Jack's dismay. Kong manages to evade them with a spectacular leap across to the roof of the North Tower. He rips off pieces of equipment from the roof and throws them at the soldiers, killing them when he throws a tank of flammable material. After ensuring Dwan's safety, Kong is attacked by helicopters equipped with machine guns, but destroys one of them. Dwan desperately pleads for the military to break off their assault and let Kong live, but the pilots only continue to attack the giant ape. Eventually, the relentless shower of bullets finally brings down Kong. As Dwan approaches the wounded Kong and puts out her hand to touch him, he rolls over the edge of the roof to his death, finally crashing to the plaza hundreds of feet below.

Dwan rushes down to comfort Kong and tearfully watches him as the giant ape takes his last breath and dies. An enormous crowd gathers around Dwan and Kong's corpse while Jack fights his way through the crowd to get to Dwan. However, he is stopped short by the crowd as she is surrounded by journalists and paparazzi, despite her cries to him.

Cast

- Jeff Bridges as Jack Prescott

- Jessica Lange as Dwan

- Charles Grodin as Fred S. Wilson

- John Randolph as Captain Ross

- René Auberjonois as Roy Bagley

- Ed Lauter as First Mate Carnahan

- Julius Harris as Crewman Boan

- Jack O'Halloran as Joe Perko

- Dennis Fimple as Sunfish

- Jorge Moreno as Garcia

- Mario Gallo as Timmons

- John Lone as Chinese Cook

- John Agar as City Official

- Sid Conrad as Petrox Chairman

- Keny Long as Ape Masked Man

- Garry Walberg as Army General

- George Whiteman as Army Helicopter Pilot

- Wayne Heffley as Air Force Colonel

- Corbin Bernsen as Reporter #1 (uncredited)

- Joe Piscopo as Reporter #2 (uncredited)

- Walt Gorney as Subway Driver (uncredited)

- Rick Baker as King Kong (suit performance, uncredited)[4]

- Peter Cullen as the voice of Kong (uncredited)

Production

There are two different accounts for how the remake for King Kong came about. In December 1974, Michael Eisner, then an executive for ABC, watched the original film on television and struck on the idea for a remake. He pitched the idea to Barry Diller, the chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures, who then enlisted veteran producer Dino De Laurentiis to work on the project. However, De Laurentiis claimed the idea to remake King Kong was solely his own when he saw a Kong poster in his daughter's bedroom as he woke her up every morning. When Diller suggested doing a monster film with him, De Laurentiis proposed the idea to remake King Kong.[5] Diller and De Laurentiis provisionally agreed that Paramount would pay half of the film's proposed $12 million budget in return for the distribution rights in the United States and Canada if the former could purchase the film rights of the original film.[6]

De Laurentiis later contacted his friend Thomas F. O'Neil, president of General Tire and RKO-General, who informed him that the film rights were indeed available. Later, De Laurentiis and company executive Frederic Sidewater entered formal negotiations with Daniel O'Shea, a semi-retired attorney for RKO-General, who requested a percentage of the film's gross. On May 6, 1975, De Laurentiis paid RKO-General $200,000 plus a percentage of the film's gross.[7] After finalizing the agreement with Paramount, De Laurentiis and Sidewater began meeting with foreign distributors and set the film's release for Christmas 1976.[8]

Writing

—Lorenzo Semple, Jr. on writing King Kong[9]

After moving his production company to Beverly Hills, De Laurentiis first met with screenwriter Lorenzo Semple, Jr., who at the time was writing Three Days of the Condor. Impressed with his work on the film, De Laurentiis contacted Semple about writing King Kong, in which Semple immediately signed on. During their collaboration on the project, De Laurentiis already had two ideas in mind—that the film would set in present day and the climax would set on top of the newly constructed World Trade Center.[10]

Because of the risen sophistication in audiences' tastes since the original film, Semple sought to maintain a realistic tone, but infuse the script with a sly, ironic sense of humor that the audiences could laugh at. Having settled on the mood, Semple retained the basic plotline and set pieces from the original film, but updated and reworked other elements of the story. Inspired by the then-ongoing energy crisis and a suggestion from his friend Jerry Brick, Semple changed the expedition to being mounted by Petrox Corporation, a giant petroleum conglomerate whom suspected that Kong's island has unrefined oil reserves. In its original story outline, Petrox would discover Kong's island from a map hidden in the secret archives at the Vatican Library.[11]

In a notable departure from the original film, Semple dropped the dinosaurs that are present with Kong on the island. The reasons for the dropped subplot was due to the increased attention on Kong and Dwan's love story and financial reasons as De Laurentiis did not want to use stop-motion animation in the film. Nevertheless, a giant boa constrictor was incorporated into the film.[11]

A fast writer, Semple completed a forty-page outline within a few days and delivered it in August 1975. While De Laurentiis was pleased with Semple's outline, he expressed displeasure with the Vatican Library subplot, which was immediately dropped. It would later be replaced with Petrox discovering the island through obtained classified photos taken by a United States spy satellite.[12] Within a month, the 140-page first draft incorporated the character of Dwan (who according to the script was originally named Dawn until she switched the two middle letters to make it more memorable), the updated rendition of Ann Darrow from the 1933 film. For its second draft, the script was reduced to 110 pages.[13] The final draft was completed by December 1975.[14]

Casting

Meryl Streep has said that she was considered for the role of Dwan, but was deemed too unattractive by producer Dino De Laurentiis.[15] Dwan was also proposed to Barbra Streisand but she turned it down.[16] The role eventually went to Jessica Lange,[17] then a New York fashion model with no prior acting experience.[18]

Filming

De Laurentiis first approached Roman Polanski to direct the picture,[19] but he wasn't interested. De Laurentiis's next choice was director John Guillermin who had just finished directing The Towering Inferno.[12] Guillermin had been developing a version of The Hurricane when offered the job of King Kong.[20]

Guillermin, who was known to have had outbursts from time to time on the set, got into a public shouting match with executive producer Federico De Laurentiis (son of producer Dino De Laurentiis). After the incident, De Laurentiis was reported to have threatened to fire Guillermin if he did not start treating the cast and crew better.[21] Rick Baker, who designed and wore the ape suit in collaboration with Carlo Rambaldi, was extremely disappointed in the final suit, which he felt was not at all convincing.[22] He gives all the credit for its passable appearance to cinematographer Richard H. Kline. The only time that the collaboration of Baker and Rambaldi went smoothly was during the design of the mechanical Kong mask. Baker's design and Rambaldi's cable work combined to give Kong's face a wide range of expression that was responsible for much of the film's emotional impact. Baker gave much of the credit for its effectiveness to Rambaldi and his mechanics.

To film the scene where the Petrox Explorer finds Dwan in the life raft, Jessica Lange spent hours in a rubber raft in the freezing cold, drenched and wearing only a slinky black dress. Although Lange was not aware of it, there were sharks circling the raft the entire time. Shooting of this scene took place in the channel between Los Angeles and Catalina Island during the last week in January 1976.

On one of the nights of filming Kong's death at the World Trade Center, over 30,000 people showed up at the site to be extras for the scene. Although the crowd was well behaved, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey (owner of the World Trade Center complex) became concerned that the weight of so many people would cause the plaza to collapse, and ordered the producers to shut down the filming. However, the film makers had already got the shot they wanted of the large crowd rushing toward Kong's body. They returned to the site days later to finish filming the scene, with a much smaller crowd of paid extras.[23]

According to Bahrenburg, five different masks were created by Carlo Rambaldi to convey various emotions.[24] Separate masks were necessary, as there were too many cables and mechanics required for all the expressions to fit in one single mask.[25] To complete the look of a gorilla, Baker wore contact lenses so his eyes would resemble those of a gorilla.[24]

Rambaldi's mechanical Kong was 40 ft (12.2 m) tall and weighed 61/2 tons.[26] It cost £500,000 to create.[27] Despite months of preparation, the final device proved to be impossible to operate convincingly, and is only seen in a series of brief shots totaling less than 15 seconds.

The roar used for Kong was taken from the film The Lost World (1960).

Music

The film's score was composed and conducted by John Barry. A soundtrack album of highlights from the score was released in 1976 by Reprise Records on LP.[28] This album was reissued on CD, first as a bootleg by the Italian label Mask in 1998,[28] and then as a legitimate, licensed release by Film Score Monthly in 2005. On October 2, 2012, Film Score Monthly released the complete score on a two-disc set; the first disc features the remastered complete score, while the second disc contains the remastered original album, along with alternate takes of various cues.[29]

- 2012 Film Score Monthly Album

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:19 |

| 2. | "Ship at Sea / Strange Tale / Hey Look" | 3:11 |

| 3. | "Montage" | 1:58 |

| 4. | "Fog Bank" | 1:34 |

| 5. | "The Island" | 2:46 |

| 6. | "Day Wall" | 3:35 |

| 7. | "Dwan Alone / Jack & Dwan" | 3:20 |

| 8. | "Night Wall Part 1" | 4:47 |

| 9. | "Night Wall Part 2" | 2:07 |

| 10. | "Celebration" | 0:46 |

| 11. | "Jungle / The Hole / Camp Site / Dwan Scared" | 2:50 |

| 12. | "Prisoner" | 2:06 |

| 13. | "Waterfall" | 2:20 |

| 14. | "Ravine" | 2:23 |

| 15. | "Acknowledge / Crater / Snake Fight" | 4:57 |

| 16. | "Chase / Trap" | 4:16 |

| 17. | "Capture" | 1:01 |

| 18. | "Super Tanker" | 1:29 |

| 19. | "Dwan Falls" | 2:56 |

| 20. | "Petrox Marching Band" | 1:37 |

| 21. | "Presentation" | 2:35 |

| 22. | "Kong Escapes" | 2:02 |

| 23. | "Into a Bar" | 1:29 |

| 24. | "Get Smashed / Alone in a Bar" | 2:18 |

| 25. | "Kong's Hand" | 0:37 |

| 26. | "Church Organ" | 0:41 |

| 27. | "World Trade Center" | 2:30 |

| 28. | "Jack in Pursuit" | 1:46 |

| 29. | "Kong's Heart Beat / End Title" | 4:28 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Opening" | 2:18 |

| 2. | "Maybe My Luck Has Changed" | 1:52 |

| 3. | "Arrival on the Island" | 2:49 |

| 4. | "Sacrifice—Hail to the King" | 7:10 |

| 5. | "Arthusa" | 2:20 |

| 6. | "Full Moon Domain—Beauty Is a Beast" | 4:24 |

| 7. | "Breakout to Captivity" | 4:08 |

| 8. | "Incomprehensible Captivity" | 2:58 |

| 9. | "Kong Hits the Big Apple" | 2:36 |

| 10. | "Blackout in New York—How About Buying Me a Drink" | 3:24 |

| 11. | "Climb to Skull Island" | 2:31 |

| 12. | "The End Is at Hand" | 1:45 |

| 13. | "The End" | 4:27 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Main Title (alternate)" | 2:21 |

| 15. | "Fog Bank (alternate)" | 1:35 |

| 16. | "Day Wall (alternate)" | 3:17 |

| 17. | "Night Wall Part 1 (alternate)" | 5:08 |

| 18. | "Night Wall Part 2 (alternate)" | 2:07 |

| 19. | "Trap (alternate)" | 3:09 |

| 20. | "Presentation (alternate #1)" | 2:37 |

| 21. | "Presentation (alternate #2)" | 3:17 |

| 22. | "End Title (alternate)" | 3:31 |

Release

Extended television version

King Kong found new and sustained life on television when NBC bought the rights to air the movie and it was a ratings success. They paid De Laurentiis $19.5 million for the rights to two showings over five years, which was the highest amount any network had ever paid for a film at that time. When King Kong made its television debut over two nights in September 1978, around 45 minutes of extra footage was inserted to make the film longer, and it had some added or replaced music cues.[30] Additionally, in order to obtain a lower, family-friendly TV rating, overtly violent or sexual scenes in the theatrical version were trimmed down or replaced with less explicit takes, and all swearing or potentially offensive language was removed.[31][32] Further extended broadcasts followed in November 1980 and March 1983.

Home media

The theatrical version of the film has been released numerous times worldwide on all known home video formats. Of the DVDs, only a few European editions feature any notable extras; these include a 2005 "Making Kong" featurette (22:20) and up to 10 deleted scenes from the extended TV version (16:10).[33] Though King Kong hasn't been released on Blu-ray in the US, most of those available are region free and completely US-friendly, including their extras.[34]

The original DVD cover showed Kong atop the World Trade Center surrounded by aircraft. Following the September 11 attacks, Paramount Home Video voluntarily recalled all retail DVD copies, and was later reissued with a different cover.

Reception

Box office

King Kong was commercially successful, earning Paramount Pictures back over triple its budget. The film ended up at fifth place on Variety's chart of the top domestic (U.S. and Canada) moneymakers of 1977.[35] (The film was released in December 1976 and therefore earned the majority of its money during the early part of 1977.)

The film opened in 1,500 theaters worldwide and grossed $26 million within ten days.[36] In the United States, King Kong opened at number one at the box office grossing $7,023,921 in its opening weekend which was Paramount's biggest opening weekend at that time, and set the record for a December opening.[37][38][39] The film went on to gross $52 million in the United States and Canada,[1] and just over $90 million worldwide.[40] It was the fourth highest grossing film of 1976 domestically,[41] and the third highest grossing film of 1976 worldwide.[42]

Critical response

After months of publicity before its release, the film received mostly mixed responses from critics, especially from admirers of the original King Kong. However, it did obtain positive reviews from some prominent critics. Pauline Kael from The New Yorker praised the film, noting "The movie is a romantic adventure fantasy-colossal, silly, touching, a marvellous [sic] Classics Comics movie (and for the whole family). This new Kong doesn't have the magical primeval imagery of the first King Kong, in 1933, and it doesn't have the Gustave Doré fable atmosphere, but it's a happier, livelier entertainment. The first Kong was a stunt film that was trying to awe you, and its lewd underlay had a carnival hucksterism that made you feel a little queasy. This new Kong isn't a horror movie-it's an absurdist love story."[43] Richard Schickel from Time wrote that "The special effects are marvelous, the good-humored script is comic-bookish without being excessively campy, and there are two excellent performances" from Charles Grodin and Jeff Bridges.[44] Variety wrote that "Faithful in substantial degree not only to the letter but also the spirit of the 1933 classic for RKO, this $22 million-plus version neatly balances superb special effects with solid dramatic credibility."[45]

Film historian Leonard Maltin cited the remake as "Addle-brained...has great potential, but dispels all the mythic and larger-than-life qualities of the original with idiotic characters and campy approach...Hardly the sort of picture one would touch after making Tootsie (for which Lange won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar, 6 years later)."

Vincent Canby, reviewing for The New York Times, claimed the movie was "inoffensive, uncomplicated fun, as well as a dazzling display of what special-effects people can do when commissioned to construct a 40-foot-tall ape who can walk, make fondling gestures, and smiles a lot." However, he was critical of the use of the World Trade Center instead of the Empire State Building during the climax, but he praised the performances by Bridges and Grodin and the special effects creation of Kong.[46] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "a spectacular film" that "for all its monumental scale retains the essential, sincere and simple charm of the beauty and the beast story."[47] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune had a mixed reaction, giving the film two-and-a-half stars out of four as he wrote, "The original 'Kong' took itself seriously; and so, even now, 43 years later, do we. But the kidding around in the new film, though frequently amusing, knocks down the myth its special effects staff has so earnestly tried to build."[48] Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the remake "moves along reasonably well as a half-jokey, half-serious contemporary 'reading' of its predecessor; as an accomplishment in horror and fantasy adventure, it does not measure up to even the small toe of the original."[49]

The movie's success helped launch the career of Jessica Lange, although she reportedly received some negative publicity regarding her debut performance that, according to film reviewer Marshall Fine, "almost destroyed her career".[50] Although Lange won the Golden Globe Award for Best Acting Debut in a Motion Picture - Female for Kong, she did not appear in another film for three years and spent that time training intensively in acting.[51]

Critical responses to King Kong continue to be mixed. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 53% based on 40 reviews with an average rating of 4.71/10. The critical consensus reads that "King Kong represents a significant visual upgrade over the original, but falls short of its classic predecessor in virtually every other respect."[52]

Accolades

The film received three Academy Award nominations and won one.

- Winner Best Visual Effects (Carlo Rambaldi, Glen Robinson and Frank Van der Veer), shared with Logan's Run (1976).[53]

- Nominee Best Cinematography (Richard H. Kline)

- Nominee Best Sound (Harry W. Tetrick, William McCaughey, Aaron Rochin and Jack Solomon).[54]

Controversy

Before Michael Eisner pitched the idea of a remake of King Kong to Barry Diller, he had earlier mentioned the idea to Sidney Sheinberg, the CEO and president of MCA Inc./Universal Pictures. Shortly after, Universal decided to purchase the property as an opportunity to showcase its new sound system technology, Sensurround, which debuted with the disaster film Earthquake, for Kong's roars. On April 5, 1975, Daniel O'Shea, a semi-attorney for RKO-General, had arranged meetings with Arnold Stane, attorney for MCA/Universal, and De Laurentiis and Sidewater for the film rights to King Kong; neither side knew that a rival studio were in negotiation. With a bargain price set $150,000, Stane had negotiated an offer of $200,000 plus 5 percent of the film's net profit. In contrast, De Laurentiis had offered $200,000 plus 3 percent of the film's gross—and 10 percent if the film recouped two and a half its negative cost. In May 1975, the film rights were granted to De Laurentiis.[5]

In the wake of the agreement, Shane claimed that O'Shea had verbally accepted Universal's offer although no official paperwork was signed. O'Shea contested, "I did not make any agreement written or oral ... never told him we had an agreement, nor words to that effect ... never told him that I had the authority ... I am not an employee, agent, or officer at RKO."[5] A few days later, Universal filed suit against De Laurentiis and RKO-General in Los Angeles Superior Court for $25 million on charges of breach of contract, fraud, and intentional interference with advantageous business relations. In October 1975, Universal, which was in pre-production with their own remake with Hunt Stromberg, Jr., as producer and Joseph Sargent as director, filed suit in a federal district court arguing that the story's "basic ingredients" were public domain.[7] Universal had claimed that their remake was based on the two-part serialization by Edgar Wallace and a novelization by Delos W. Lovelace adapted from the screenplay that had been published shortly before the film's release in 1933.[5]

On November 12, 1975, Universal announced it would start production on The Legend of King Kong on January 5, 1976 with Bo Goldman writing the screenplay based on the novelization by Lovelace.[55] On November 20, RKO-General countersued Universal for $5 million alleging that The Legend of King Kong was an infringement on their copyright, and asked the court to prevent any "announcements, representations, and statements" on their proposed film. On December 4, De Laurentiis countersued for $90 million with charges of copyright infringement and "unfair competition".[56] In January 1976, both studios agreed to withdraw their legal suits filed against each other. Universal agreed to cancel The Legend of King Kong, but intended to proceed with a remake sometime in the future although on the condition to release it eighteen months after De Laurentiis's remake.[57][58] In September 1976, a federal judge ruled in favor of Universal that Lovelace's novelization had fallen into public domain which cleared the studio to produce a remake.[59] Universal would later make its own remake, also titled King Kong in 2005.

References

- Notes

- "King Kong (1976)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Knoedelseder Jr., William K (August 30, 1987). "De Laurentiis Producer's Picture Darkens". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- "King Kong, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- Lambie, Ryan (March 10, 2017). "The Struggles of King Kong '76". Den of Geek. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- Tobias, Andrew (February 23, 1976). "The Battle for King Kong". New York. Vol. 9 no. 8. pp. 38–44. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved July 30, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Morton 2005, p. 150.

- Champlin, Charles (November 5, 1975). "A Ding-Dong King Kong Battle". Los Angeles Times. p. Part IV, p. 1. Retrieved July 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Morton 2005, p. 151.

- Swires, Steve (October 1983). "Lorenzo Semple, Jr. The Screenwriter Fans Love to Hate - Part 2". Starlog. No. 75. pp. 45–47, 54. Retrieved May 28, 2014 – via Internet Archive.

- Morton 2005, p. 152.

- Morton 2005, p. 153.

- Morton 2005, pp. 154–5.

- Morton 2005, p. 155–6.

- Morton 2005, p. 160.

- "Meryl Streep's worst audition". The Graham Norton Show. Series 16. Episode 13. January 9, 2015. BBC.

- Medved, Michael, and Harry Medved. The Golden Turkey Awards. 1980, Putnam. ISBN 0-399-50463-X.

- Manders, Hayden (November 11, 2015). "This Meryl Streep Mic Drop Is Too Good To Be True". Nylon. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Scott, Vernon (January 20, 1976). "King Kong Is Coming Back with International Flavor". United Press International. Fort Lauderdale News. p. 4B. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bahrenburg 1976, p. 19.

- Goldman, Lowell (November 1990). "Lord of Disaster". Starlog. p. 61.

- Morton 2005, p. 93.

- Morton 2005, p. 209.

- Bahrenburg 1976, pp. 218–28.

- Bahrenburg 1976, p. 177.

- Bahrenburg 1976, pp. 176–77.

- Bahrenburg 1976, p. 204.

- Foley, Charles (July 12, 2014). "From the Observer archive 11 July 1976: King Kong dogged by costly mishaps". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- "King Kong- Soundtrack details - SoundtrackCollector.com". www.soundtrackcollector.com.

- "King Kong: The Deluxe Edition (2-CD)". Film Score Monthly. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- "'King Kong,' 'Airport '77' Get Footage Added For NBC Airings". Variety. August 9, 1978. p. 1.

- "King Kong (1976) Theatrical Cut-TV Extended Version Comparison". Movie-Censorship.

- "King Kong (1976) Theatrical Cut-TV Extended Version Comparison #2". Movie-Censorship.

- "King Kong (1976) DVD comparison". DVDCompare.

- "King Kong (1976) Blu-ray comparison". DVDCompare.

- "Big Rental Films of 1977". Variety. January 4, 1978. p. 21.

- "'King Kong' Trails 'Jaws' In Early Take". The News Journal. December 31, 1976. p. 19. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. December 29, 1976. p. 9.

- Verrill, Addison (December 22, 1976). "'Kong' Wants 'Jaws' Boxoffice Crown". Variety. p. 1.

- "King Kong (1976)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "Business Data for King Kong". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- "Top 1976 Movies at the Domestic Box Office". The Numbers. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- "Top 1976 Movies at the Worldwide Box Office". The Numbers. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- Kael, Pauline. "King Kong Reviews". GeoCities. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Schickel, Richard (December 27, 1976). "The Greening of Old King". Time. Vol. 108 no. 26. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- "King Kong". Variety. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Canby, Vincent (December 18, 1976). "'King Kong' Bigger, Not Better, In a Return to Screen of Crime". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Champlin, Charles (December 12, 1976). "A Smashing 'King Kong II'". Los Angeles Times Calendar, p. 1, 114.

- Siskel, Gene (December 17, 1976). "Original 'Kong' still king, but this one's good for laughs". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 1.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (February 1977). "King Kong". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 44 (517): 25.

- Fine, Marshall. Editorial Reviews. ASIN 6305495181.

- "Jessica Lange". Jessica Lange Fansite. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- "King Kong (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- "The 49th Academy Awards (1977)". oscars.org. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- Murphy, Mary (November 12, 1975). "Anjelica's Visage Wins Role". Los Angeles Times. p. Part IV, p. 11. Retrieved July 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Morton 2005, p. 162.

- "Producers Settle Dispute on 'King Kong' Remakes". Los Angeles Times. January 30, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Morton 2005, p. 166.

- "Kong Goes Public". The Atlanta Constitution. September 16, 1976. p. 2–B. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: King Kong (1976 film) |

- King Kong at IMDb

- King Kong at AllMovie

- King Kong at Box Office Mojo

- King Kong at Rotten Tomatoes

- King Kong at the TCM Movie Database