Kentisuchus

Kentisuchus is an extinct genus of tomistomine crocodylian. It is considered one of the most basal members of the subfamily. Fossils have been found from England and France that date back to the early Eocene.[1] The genus has also been recorded from Ukraine, but it unclear whether specimens from Ukraine are referable to Kentisuchus.[2][3]

| Kentisuchus Temporal range: Early Eocene | |

|---|---|

| |

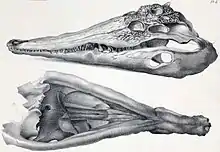

| K. spenceri skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Subfamily: | Tomistominae |

| Genus: | †Kentisuchus Mook, 1955 |

| Species | |

Species

The genus Kentisuchus was erected by Charles Mook in 1955 for the basal tomistomine "Crocodylus" toliapicus, described by Richard Owen, in 1849. William Buckland named "Crocodylus" spenceri on the basis of a partial skull found from the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, England.[4][5][6] In 1888 Richard Lydekker considered "C." toliapicus synonymous with "C." champsoides and "C." arduini, named by De Zigno, and reapplied the name "C." spenceri to all of these species.[7][8]

The genus name Kentisuchus was constructed only after it was realized that these tomistomine specimens were clearly distinct from the genus Crocodylus and that some specimens originally assigned to "C." spenceri belonged to entirely different genera and species. "C." arduini was reassigned to the new genus Megadontosuchus in the same paper that Kentisuchus was first described in. A 2007 review of European Eocene tomistomines synonymized K. toliapicus and K. champsoides with K. spenceri.[9]

Phylogenetics

K. spenceri is closely related to Megadontosuchus and Dollosuchoides.[10][11][12] An apparent close relationship between K. spenceri and Eosuchus lerichei has been used to imply that the latter species was a tomistomine, while it is now thought that Eosuchus is a basal gavialoid that is crownward to most other members of the superfamily.[13][14][15]

Paleobiology

The close relation of Kentisuchus and Dollosuchoides, which are known from European localities that were on the mainland during the early Eocene, to Megadontosuchus, which is known from Italian localities that were once part of a Tethysian archipelago, suggests that it came to these islands after a tomistomine dispersal event south from mainland Europe rather than north from Africa.[16]

References

- Stéphane Jouve (2016). "A new basal tomistomine (Crocodylia, Crocodyloidea) from Issel (Middle Eocene; France): palaeobiogeography of basal tomistomines and palaeogeographic consequences". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 177 (1): 165–182. doi:10.1111/zoj.12357.

- Efimov, M. B. (1993). The Eocene crocodiles of the GUS — a history of development. Kaupia 3:23–25.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226149319_On_a_tomistomine_crocodile_Crocodylidae_Tomistominae_from_the_Middle_Eocene_of_Ukraine

- Mook, C. C. (1955). Two new genera of Eocene crocodilians. American Museum Novitates 1727:1-4.

- Buckland, W. (1836). Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology. 618 pp. Pickering, London.

- OWEN, R. 1850. Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the London Clay, and of the Bracklesham and other Tertiary beds, part II: Crocodilia (Crocodilus, etc.). Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society, London, 50 pp.

- De Zigno, A. (1880). Sopra un cranio di coccodrillo scoperto nel terreno Eoceno del Veronese. Mem. R. Accad. Lincei, ser. 3, Cl. Sci. Fip., Mat., Nat., vol. 5, pp. 65-72.

- Lydekker, R. (1888). Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia in the British Museum. London, pp. 60-63.

- Brochu, C. A. (2007). Systematics and taxonomy of Eocene tomistomine crocodylians from Britain and Northern Europe. Palaeontology 50(4):917-928

- Piras, P., Delfino, M., Del Favero, L., and Kotsakis, T. (2007). Phylogenetic position of the crocodylian Megadontosuchus arduini and tomistomine palaeobiogeography. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52(2):315–328.

- Jouve, S. (2004). Etude des crocodyliformes fini Crétace−Paléogène du Bassin de Oulad Abdoun (Maroc) et comparaison avec les faunes africaines contemporaines: systématique, phylogénie et paléobiogéographie. Ph.D. thesis. 652 pp. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, Paris.

- Delfino, M., Piras, P., and Smith, T. (2005). Anatomy and phylogeny of the gavialoid crocodylian Eosuchus lerichei from the Paleocene of Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 50:565–580.

- Brochu, C. A. (1997). Phylogenetic Systematics and Taxonomy of Crocodylia. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. 467 pp. University of Texas, Austin.

- Brochu, C. A. (2001). Crocodylian snouts in space and time: phylogenetic approaches toward adaptive radiation. American Zoologist 41:564–585.

- Delfino, M., Piras, P., and Smith, T. (2005). Anatomy and phylogeny of the gavialoid crocodylian Eosuchus lerichei from the Paleocene of Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 50(3):565–580.

- Kotsakis, T., Delfino, M., and Piras, P. (2004). Italian Cenozoic crocodilians: taxa, timing and palaeobiogeographic implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 210(1):67-87.

External links

- Kentisuchus in the Paleobiology Database