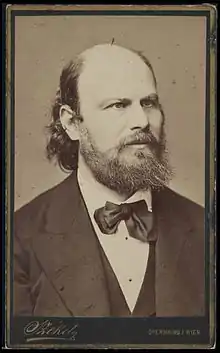

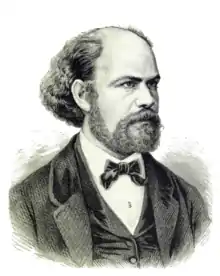

Julius Anton Glaser

Julius Anton Glaser (born Joshua Glaser[1] 19 March 1831 – 26 December 1885) was an Austrian jurist and classical-liberal politician. Along with Joseph Unger he is considered to be one of the founders of modern Austrian jurisprudence.

Julius Anton Glaser | |

|---|---|

Julius Anton Glaser. | |

| Born | Joshua Glaser 19 March 1831 |

| Died | 26 December 1885 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Occupation | Jurist |

| Spouse(s) | Wilhelmine Löwenthal |

He joined the Auersperg cabinet as Minister of Justice in 1871. Upon resigning this office in 1879, he was appointed attorney-general at the Vienna Court of Cassation, a position he held until his death. Glaser was a prominent representative of Austrian High Liberalism, with a particular emphasis on the cultural and political preeminence of the German part of the Empire. He was responsible for several liberal penal law reforms, most notably the 1873 Austrian Code of Criminal Procedure, and he advocated the abolition of the death penalty.

Life

Born in Postelberg, Bohemia to a family of Jewish traders of humble means,[2] Glaser later converted to Christianity. In 1849, at the age of 18, he attained his doctorate of philosophy at the University of Zürich and gained a reputation as a criminalist thanks to a monograph on English and Scottish criminal procedure (Das englisch-schottische Strafverfahren, Vienna, 1850). In 1854, after also obtaining a doctorate of law in Vienna, he achieved habilitation as Privatdozent for Austrian criminal law at the University of Vienna. In 1856 he was appointed associate professor of criminal law,[3] and in 1860, ordinary (tenured) professor.[1]

In 1871 he entered the Auersperg cabinet as Minister of Justice.[4] Resigning this office in 1879, he was appointed Attorney-General at the Vienna Court of Cassation, which position he held until his death. From 1871 to 1879 he represented Vienna in the House of Representatives as a member of the Liberal party, and later became a member of the House of Lords.[1] A prominent representative of Austrian High Liberalism, he particularly emphasized the cultural and political preeminence of the German part of the Empire.[4]

He died in 1885 of pneumonia, leaving behind a widow, Wilhelmine (née Löwenthal), a son and two daughters. They obtained the hereditary title of Freiherr to which Glaser's decorations had entitled him.[2]

Legacy

Described as a "liberal reformer of Austrian penal law",[5] along with Joseph Unger he is considered to be one of the founders of modern Austrian jurisprudence.[6] Glaser's principal legislative accomplishment was the 1873 Austrian Code of Criminal Procedure, the first Austrian code to introduce the principles of immediacy and publicity, trial by jury, and trial based on specific charges (Anklageprinzip).[4] As a scholar, he is best remembered for his Handbook of Criminal Procedure (1883/85), a systematic overview of German criminal procedure with wide-ranging comparative and historical notes.[4] He advocated introducing jury courts and opposed the death penalty.[3]

Among other decorations, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold and made a Knight of the Order of the Iron Crown. A marble relief portrait by Zumbusch[2] adorns the Arcaded Courtyard of the University of Vienna, the first statue to be placed there.[3]

Noted works

- Anklage, Wahrspruch und Rechtsmittel im englischen Schwurgerichtsverfahren. Erlangen, Enke, 1866, reprinted 1997, ISBN 3-8051-0395-6

- Das englisch-schottische Strafverfahren, Vienna, 1850

- Abhandlungen aus dem österreichischen Strafrecht, Vienna 1858

- Anklage, Wahrspruch und Rechtsmittel im englischen Schwurgerichtsverfahren, Erlangen, 1866

- Gesammelte kleinere Schriften über Strafrecht, Zivil- und Strafprozeß, Vienna, 1868

- Studien zum Entwurf des österreichischen Strafgesetzes über Verbrechen und Vergehen, Vienna, 1871

- Schwurgerichtliche Erörterungen, Vienna, 1875

- Beiträge zur Lehre vom Beweis im Strafprozeß, Leipzig, 1883

References

- Singer & Haneman 1906.

- Benedikt 1904, p. 372-80.

- Scholars in Stone and Bronze: The Monuments in the Arcaded Courtyard of the University of Vienna. Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2008. p. 57. ISBN 978-3-205-78224-7.

- Neumair 2001, p. 246.

- Janik & Veigl 1998, p. 69.

- Hornung 1899, p. 64.

- Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Isidore Singer and Frederick T. Haneman (1901–1906). "Glaser, Julius Anton". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Isidore Singer and Frederick T. Haneman (1901–1906). "Glaser, Julius Anton". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Benedikt, Edmund (1904). Glaser, Julius (in German). Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German) 49, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glaser, Wilhelmine (1888). : Julius Glaser. Bibliograph (in German). Verzeichn. s. Werke, Abhandl., Gesetzentwürfe u. Reden. (Vorr.: Josef Unger), Vienna.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hornung, Ernest William (1899). Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-0869-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Janik, Allan; Veigl, Hans (1 January 1998). Wittgenstein in Vienna: A biographical excursion through the city and its history. Springer. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-211-83077-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neumair, Michael (2001). "Glaser, Julius". In Michael Stolleis (ed.). Juristen: ein biographisches Lexikon; von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (in German) (2nd ed.). München: Beck. ISBN 3-406-45957-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1916). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk and Wagnalls.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)