Joseph Stannard

Joseph Stannard (13 September 1797 – 7 December 1830) was an English marine, landscape and portrait painter. He was a talented and prominent member of the Norwich School of painters.

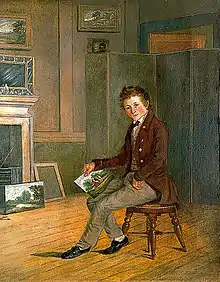

Joseph Stannard | |

|---|---|

Portrait by George Clint (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections | |

| Born | 13 September 1797 |

| Died | 7 December 1830 (aged 33) Norwich |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Norwich Grammar School |

| Known for | Landscape and marine painting |

Notable work | Thorpe Water Frolic, Afternoon |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

| Spouse(s) | Emily Stannard |

After attending the Norwich Grammar School, his parents paid for him to be trained as an artist by Robert Ladbrooke, one of the founding members of the Norwich Society of Artists. During his career he exhibited in both Norwich and London, with some success. In 1816 he joined a rival society in Norwich, which lasted a few years. He was influenced by the work of the Dutch masters, whose works he studied and copied following a visit to Holland in 1821. His own most important painting, Thorpe Water Frolic, Afternoon, was first exhibited in Norwich in 1825.

In 1826 he married the artist Emily Coppin. Several other members of his family, including their daughter Emily, were talented artists. He suffered from poor health during most of his life and died from tuberculosis in 1830, aged only 33.

Background

Joseph Stannard belonged to the Norwich School of painters, all of whom that were connected personally or professionally. Though they were mainly inspired by the Norfolk countryside, many also depicted coastal and urban scenes. [1] Its most important members were John Crome and John Sell Cotman—the leading spirits and finest artists of the movement[2]—as well as Stannard,[3] James Stark, George Vincent,[4] Robert Ladbrooke [5] and Edward Thomas Daniell, the best etcher of the school.[6] Stannard belonged to the second generation, which also included John Berney Crome, Stark, Vincent and Miles Edmund Cotman.[7]

According to the art historian Andrew Moore, the Norwich School "has long been recognised as a unique phenomenon in the history of 19th-century British art."[2] Norwich was the first English city outside London with the right conditions for a provincial art movement.[8][9] It had more locally born artists than any similar city,[10] and its theatrical, artistic, philosophical and musical cultures were cross-fertilised in a way that was unique outside the capital.[8][11] The Norwich Society of Artists, founded by Crome and Ladbrooke in 1803,[12] arose from the need for artists in the city to teach each other and their pupils. It held regular exhibitions and had an organised structure, showing works annually until 1825 and again from 1828 until it was dissolved in 1833.[13] The first group of its kind to be created since the formation of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, it was remarkable in acting in its artists' interests for 30 years—a longer period than for any similar group.[14]

Life and family

Joseph Stannard was born close to St Andrew's Church, Norwich on 13 September 1797.[15][16] He was the elder son of Abraham Stannard, who was possibly a musician, and Mary Bell,[17] and was baptised by his parents on 17 September at St Michael-at-Plea, Norwich.[18][19] He attended Norwich Grammar School and his early artistic talents encouraged his parents to ask the prominent landscape artist John Crome to take on Joseph as a pupil. Crome was at time Norwich's most famous artist, and his fees proved to be too high for the Stannards, so they paid for their son to be apprenticed by Robert Ladbrooke in the city.[15][20] Ladbrooke, who had already given him informal lessons, was able to teach the young artist to become a skilled draughtsman, with the potential to develop his own style. Impressed by Stannard's ability, he even waived his tuition fees, offering an annual payment of £10 to entice him to work in his studio.[15] Stannard stayed as Ladbrooke's pupil for seven years,[16] although there is little evidence of his master's influence in his artistic style.[21] When Ladbrooke seceded from the Norwich Society of Artists in 1816, Stannard sided with him.[20][22]

He met and got to know his fellow artist Emily Coppin in 1820 when attending meetings of the Norwich Society of Artists,[23][24] and in 1826 they were married. She had been influenced by a visit to Holland with her father, the artist Daniel Coppin, where there was the opportunity for her to study the techniques of the Dutch still life painters,[23] and copy works by Jan van Huysum.[25] Emily Coppin Stannard was a notable painter of fruit and flowers, who received three gold medals from the Norwich Society of Arts and was still painting 50 years after her husband's death.[26] In 1823 the Norwich Mercury wrote of her that "she is an honour to art, an honour to the city, and an honour to her sex, by the taste, industry, and knowledge, her beautifully disposed and elaborately finished pictures display."[27]

The Stannards belonged to an artistic family.[21] Their daughter Emily, who was born in Norwich in 1827, was a still life painter and a teacher, who exhibited with the Norfolk and Norwich Association in 1856 and the Norwich Industrial Exhibition in 1867.[25] Their niece Eloise Harriet Stannard and her younger brother Alfred George Stannard were both artists, as was Joseph's brother Alfred Stannard.[28]

Stannard's paintings depict the local scenery around Norwich and the Norfolk coast, which he enjoyed exploring.[15] He was an excellent oarsman and a skilled ice-skater; crowds would gather to watch him perform on the ice.[29]

He contracted tuberculosis two years after his marriage, and suffered from poor health for much of his later life.[30] Friends and relatives rallied to support him as his illness developed. To try and recuperate, he stayed at the sea-side resort of Great Yarmouth, which resulted in the oil painting Yarmouth Beach and Jetty. He died from tuberculosis on 7 December 1830, aged 33,[31] having lived in Norwich all his life.[15] His death was announced in the Bury and Norwich Post: "Same day, in St. Giles's Terrace, aged 34, Mr. Joseph Stannard, artist, in whom Norwich has lost a talented citizen, and art a favoured and most deserving votary."[32] He is buried, together with an infant daughter and his sister Eloise, in the Church of St John Maddermarket, Norwich.[33]

Emily Coppin Stannard, who was to outlive her husband by nearly 55 years, died on 6 January 1885; her daughter Emily, whose father had died when she was two years old, was trained to be artist by her mother, and assisted her in her work as a teacher. She died in 1894, having lived in Norwich most of her life.[26]

Career

.jpg.webp)

Joseph Stannard was one of the most important members of the Norwich School of Artists. even though his career lasted only fifteen years and his output was affected by illness.[3][34] The art historians Josephine Walpole and Andrew Hemingway both rank him as the most distinguished painter of the school after John Crome and John Sell Cotman.[15][35] A precocious artist, he began exhibiting when still a boy; one of his paintings was exhibited at the Norwich Society of Artists in 1811, when he was 14. He was praised by the local press in 1817, when the Norfolk Chronicle noted that he was "a rising genius",[21] and there was a positive review of his work in The Norwich Mercury in August 1818.[36]

In 1816, Stannard, Robert Ladbrooke and his sons, James Sillett and John Thirtle seceded from the Norwich Society of Artists to form their own society.[37] Led by Ladbrooke, seven members of the Norwich Society opened an exhibition entitled 'The Twelfth of the Norfolk and Norwich Society of Artists', which was held in the Shakespeare Tavern, on Theatre Plain.[38] Stannard exhibited five works in the first year of the new society's existence: Study from Nature; Distant View of Norwich from Whitlingham;.Pencil Sketches; View of the Foundry Bridge and View of the City from Fuller's Hole, exhibiting 13 works with the society in total.[16] The Society was dissolved after three years.[39]

He developed an interest in the stage and made connections with Norwich's Theatre Royale from 1819–1820, which resulted in works such as A Scene in the Melodrama of the "Broken Sword", A Portrait of Mrs. Hammond, of the Theatre Royal, Norwich and A Portrait of Mr. Beacham, in the character of Riber.[40] In 1819 he exhibited in London. The same year he showed Scene in a Norwich Alehouse, his only picture to receive a review in the local press. The Norwich Mercury described it as "nicely wrought", noting that "it depicted all the well-known iterants of the city".[41]

Between 1820 and 1829, Stannard exhibited works at the Royal Academy and the British Institution in London, showing eight works at the British Institution from 1824 to 1828 (Breydon, looking towards Yarmouth; Mundesley Cliffs, looking towards Cromer; A View near Norwich; Breydon—Morning; On the Norwich River; A Marine View; Gorleston Pier—Pilot Boats Going Off and Fresh Breeze, Lowestoft Roads).[42] He was influenced by the work of earlier Dutch artists, whose works he studied and copied during a visit to Holland in 1821 that was perhaps inspired by a similar visit by his future wife and her father in 1820.[19][23]

By 1823 he was suffering financially, a situation created by the patronage of the Norwich manufacturer and entrepreneur John Harvey, who commissioned Stannard to paint Thorpe Water Frolic, Afternoon. Harvey, who perhaps had not realised the large cost of the work, declined to accept it, and Stannard was left unable to recover his expenses.[29] In 1823 he left Emily Coppin in Norwich and went to London, where he sat for his portrait by William Beechey, and was possibly employed by the artist William Anderson.[43][44] By 1824, with his debts cleared, he was working again in Norwich.[29]

In 1827 a collection of his etchings were published as Norfolk Etchings.[28] The artist John Middleton was his pupil,[45] but he was not a teacher and usually had no pupils. From 1824 he taught his friend Edward Thomas Daniell how to etch.[46][47] Daniell, then a student at Oxford University, workied with Stannard during his holidays, and as Daniell's ability developed, the relationship between pupil and teacher became more equal.[48][47] Daniell sued him when a newly built studio obscured his light; Stannard was forced to remove it after losing the case.[48]

Thorpe Water Frolic, Afternoon

Stannard's masterpiece—his best known work and his most important commission[30]—is Thorpe Frolic, Afternoon (1824), an oil painting that shows a large civic regatta. The annual 'frolic' was that year attended by almost 20,000 spectators, at a time when the population of Norwich was approximately 50,000.[49] Part sporting event and part social occasion, the event was held on the river Yare at Thorpe, east of Norwich.[50] It was organised by John Harvey, who aspired to promote the city as an international port, and entailed sailing and rowing competitions, picnics, speeches and music.[49]

The painting it was first exhibited in Norwich in 1825,[51] the year the Norfolk Chronicle wrote "of all the gay, the bustling, the delightful scenes in nature, we know of none more refreshing and enchanting than a 'Water Frolic'."[49] It was commissioned by Harvey in 1823, who asked for "the finest painting you can", and the work involved in producing the large oil-on-canvas work 42.7 by 67.8 inches (108 cm × 172 cm) meant that for five months it took precedence over all other undertakings. The high production costs were in the end borne by Stannard and not Harvey, whose financial situation had deteriorated following the end of the Napoleonic wars [30][29]

The scene has no mythological imagery, suggestion of pageantry or notion of any patriotism, but a costumed gondolier in his boat is shown, suggestive of the regattas of Venice, adding a new dimension.[49] Stannard shows the beauty of the setting by painting in the fields beyond the river, woodland, and the buildings of the gentry, whilst also recreating the event using his artistic licence.[52] Thorpe Frolic, Afternoon was praised by the Norfolk Chronicle, which described the work as "intensely interesting, masterly and elegant". The Norwich Mercury also admired his painting, noting it to be a work of great skill, and adding that it was a striking blend of fact and fiction.[53] The painting is on display at Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.[54] The naval historian Oliver Warner, who congratulated Stannard on the work, describing it as "entrancing" and adding that it is "a picture good enough in itself to justify a long journey".[55]

Technique

Stannard painted chiefly river and coastal landscapes in oil.[3] As an oil painter he has more in common with the Dutch masters than with Crome or Cotman.[3] In Holland he sketched the local scenery, depicting rivers and coastline in pencil and crayon.[23] His visit to Holland enabled him to develop a new oil technique and deepen his interest in marine subjects.[23] According to Walpole, who regards Stannard as close to being Britain's most significant marine artist, his paintings betray his love of the sea as a subject, and are depicted with "inherent skill and devastating honesty to produce some of the most poetic and sensitive sea paintings of all time".[23]

A few watercolours can be attributed to him, including Lugger in a Squall, with a small number owned by Norfolk Museums.[3] An excellent draughtsman,[3] his accomplished pencil drawings (and perhaps some of his oil paintings) were made in situ. The drawings were often made in preparation of larger works.[23] He was a talented figure drawer; in Moore's opinion, "Stannard's excellence in figure drawing among the Norwich painters may be seen in his watercolour studies, equalled only by the Joy brothers of Yarmouth."[21] In the opinion of author Derek Clifford, Stannard "was a shining exception to the Norwich landscapists' inability to draw the human figure."[3]

He was a talented portrait painter, and by 1818 had received a number of commissions. He produced character studies; his Norwich Ratcatcher is perhaps the best known of these works, which, alongside Old Lying Plummer, Scene in a Norwich Alehouse and Joe Doe the Butcher's Porter, have what Walpole describes as "the same characteristic feeling of identity".[15]

His restricted output of 12 etchings were issued in small numbers, or—as with Unloading Ships—not issued at all; they are prized for both their rarity and quality.[56] The author Geoffrey Searle describes Stannard as an original and distinguished etcher who talents approached those of John Crome, John Sell Cotman and Edward Daniell, describing Boats on Breydon as "glorious" and Mundesley Beach as having "an uncompromisingly gloomy splendour".[57] He skilfully portrayed human figures, typically depicted within their working environment, and revealing their personalities in a way that was unusual among the Norwich School etchers.[58] Stannard's prints of his etchings were for his friends and not for profit, and so are modest in size.[59] After his death an edition of his etchings was produced. No copies are known to have survived.[56]

Gallery

Buckenham Ferry, on the River Yare, Norfolk (1826), Yale Center for British Art

Buckenham Ferry, on the River Yare, Norfolk (1826), Yale Center for British Art Fisherboy (undated}, British Museum

Fisherboy (undated}, British Museum A Fresh Breeze (undated), Norfolk Museums Collection

A Fresh Breeze (undated), Norfolk Museums Collection Wherries (undated), Norfolk Museums Collection

Wherries (undated), Norfolk Museums Collection Off Corton (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections

Off Corton (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections Sketches for The Thorpe Water Frolic

Sketches for The Thorpe Water Frolic Lugger in a Squall (undated), private collection

Lugger in a Squall (undated), private collection Beach at Mundesley (1827), Yale Center for British Art

Beach at Mundesley (1827), Yale Center for British Art

Legacy

Stannard remained an obscure artist during most of the 19th century, perhaps due to his early death in 1830 and because he did not try to make his name by living away from Norwich. His popularity as an artist was affected by the relatively small number of works produced, and the tendency for them to be sold in London rather than in Norwich.[60] it is possible that most of his early works were in imitation of the old masters, explaining why he remained unnoticed by the local press until the 1820s.[61]

References

- Hemingway 2017, pp. 181–182.

- Moore 1985, p. 9.

- Clifford 1965, p. 45.

- Cundall 1920, p. 3.

- Clifford 1965, p. 22.

- Walpole 1997, p. 158.

- Hemingway 1979, p. 8.

- Cundall 1920, p. 1.

- Day 1968, p. 7.

- Hemingway 1979, pp. 9, 79.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 10–11.

- Dickes 1905, p. 175.

- Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 4.

- Moore 1985, pp. 11, 15.

- Walpole 1997, p. 53.

- Dickes 1905, p. 525.

- Day 1966, p. 9.

- Joseph Stannard in "Parish register transcripts", FamilySearch (Joseph Stannard).

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. 54. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 85.

- Day 1969, p. 157.

- Moore 1985, p. 95.

- Goldberg 1978, p. 142.

- Walpole 1997, p. 54.

- Day 1966, p. 13.

- Burbidge 1974, p. 36.

- Gray 2009, p. 249.

- Clifford 1965, p. 46.

- Cundall 1920, p. 31.

- Day 1969, p. 158.

- Walpole 1997, p. 55.

- Goldberg 1978, p. 146.

- "Norwich, Dec. 15". Bury and Norwich Post (2529). Bury St. Edmunds. 15 December 1830. p. 3. Retrieved 14 November 2020. (subscription required)

- "Norwich, St John Maddermarket". Ledgerstone Survey of England & Wales. The Ledgerstone Survey. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Day 1969, p. 161.

- Hemingway 1979, p. 67.

- Hemingway 1979, pp. 10, 17.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 25–26.

- Dickes 1905, p. 103.

- Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 3.

- Dickes 1905, p. 526.

- Moore 1985.

- Dickes 1905, p. 527.

- Goldberg 1978, p. 144.

- Day 1966, p. 16.

- Clifford 1965, p. 75.

- Walpole 1997, p. 157.

- Searle 2015, p. 65.

- Clifford 1965, p. 50.

- Fawcett 1977, p. 393.

- Fawcett 1977, p. 395.

- Goldberg 1978, p. 145.

- Fawcett 1977, pp. 394, 397.

- Fawcett 1977, p. 397.

- "Thorpe Water Frolic, Afternoon (painting)". Norfolk Museums Collections. Norfolk Museums. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Warner 1948, p. 39.

- Searle 2015, p. 60.

- Searle 2015, pp. 60, 62, 124.

- Searle 2015, pp. 60, 112.

- Searle 2015, pp. 60, 71.

- Hemingway 1979, pp. 67–67.

- Hemingway 1979, p. 68.

Bibliography

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stannard, Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 782.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stannard, Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 782.

- Burbidge, Robert Brinsley (1974). A dictionary of British flower, fruit, and still life painters. 1. Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis. ISBN 9-780-85317-024-2.

- Clifford, Derek Plint (1965). Watercolours of the Norwich School. London: Cory, Adams & Mackay. ISBN 978-0-239-00015-6. OCLC 1624701.

- Cundall, Herbert Minton (1920). Holme, Geoffrey (ed.). The Norwich School. London: Geoffrey Holme Ltd. OCLC 651802612.

- Day, Harold A E (1966). Life and work of Joseph Stannard 1797–1830. Eastbourne: Eastbourne Fine Art. OCLC 1113261992.

- Day, Harold (1968). East Anglian Painters. II. Eastbourne, UK: Eastbourne Fine Art. OCLC 314628502.

- Day, Harold (1969). East Anglian Painters. III. Eastbourne, UK: Eastbourne Fine Art. OCLC 935923078.

- Dickes, William Frederick (1905). The Norwich school of painting: being a full account of the Norwich exhibitions, the lives of the painters, the lists of their respecitve exhibits and descriptions of the pictures. Norwich: Jarrold & Sons Ltd. OCLC 558218061.

- Fawcett, Trevor (1977). "Thorpe Water Frolic". Norfolk Archaeology. 36 (4): 393–398. ISSN 0142-7962.

- Goldberg, Norman L (1978). John Crome the Elder. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2957-1. (registration required)

- Gray, Sara (2009). The Dictionary of British Women Artists. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. ISBN 9-781-78684-235-0.

- Hemingway, Andrew (1979). The Norwich School of Painters 1803–1833. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-2001-9.

- Hemingway, Andrew (2017). "Cultural Philanthropy and the Invention of the Norwich School". Landscape between ideology and the aesthetic: Marxist essays on British art and art theory, 1750-1850. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 181–213. ISBN 9-789-00426-900-2.

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. Norwich: HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 978-0-11-701587-6.

- Rajnai, Miklos; Stevens, Mary (1976). The Norwich Society of Artists, 1805–1833: a dictionary of contributors and their work. Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. ISBN 978-0-903101-29-5.

- Searle, Geoffrey R. (2015). Etchings of the Norwich School. Norwich: Lasse Press. ISBN 978-0-95687-589-1.

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-261-9.

- Warner, Oliver (1948). An introduction to British marine painting. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. OCLC 1150046398.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joseph Stannard. |

- Works relating to Stannard kept by the Norfolk Museums Collections

- Works by Stannard at the ArtUK website

- Works by Stannard at the Yale Center for British Art

- Prints by Stannard in the British Museum

- Works by Stannard held by the National Trust