José María Lamamié de Clairac y Colina

José María Lamamié de Clairac y Colina (1887-1956) was a Spanish politician. He supported the Traditionalist cause, until the early 1930s as an Integrist and afterwards as a Carlist. Among the former he headed the regional León branch, among the latter he rose to nationwide executive and became one of the party leaders in the late 1930s and the 1940s. In 1931-1936 he served 2 terms in the Cortes; in 1915-1920 he was member of the Salamanca ayuntamiento. In historiography he is known mostly as representative of Castilian terratenientes; as president of Confederación Nacional Católico-Agraria he tried to preserve the landowner-dominated rural regime, first opposing the Republican and later the Francoist designs.

José María Lamamié de Clairac y Colina | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1887 Salamanca, Spain |

| Died | 1956 Salamanca, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | landowner |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Integrism, Carlism |

Family and youth

The Lamamiés originated from the French Languedoc;[1] Etienne La Mamye de Clairac[2] was a military and held high administrative posts in Flanders in the late 17th century.[3] His son arrived in Spain with Felipe de Anjou in the 1720s and became known as Claudio Lamamié de Clairac y Dubois;[4] he served on various military command posts during the following 4 decades.[5] Claudio’ son Miguel Lamamié de Clairac y Villalonga[6] was the first to settle on estates granted to him near Salamanca in the late 18th century.[7] His son and the grandfather of José María, José Ramón Lamamié de Clairac y Tirado (1784-1847),[8] a military like his ancestors, fought against the French during Napoleonic wars; though he massively benefitted from liberal desamortización,[9] he turned a Carlist supporter when senile.[10] His son and the father of José María, Juan Lamamié de Clairac y Trespalacios (1831-1919),[11] was among the largest provincial landowners.[12] Detained for plotting a legitimist rising,[13] he returned from exile in the 1870s; he then owned numerous Carlist provincial periodicals.[14] In the 1880s Lamamié joined the breakaway Integrist branch of Traditionalism and was its regional León jefé; in 1907-1910 he served as Integrist MP[15] in the Cortes[16] and entered the national party executive.[17]

Following childless death of his wife, in 1882 Lamamié de Clairac y Trespalacios remarried[18] with Celestina de la Colina Fernández-Cavada (1859-1946), the native of Burgos.[19] The couple had at least 8 children, born when the father was in his 50s and 60s;[20] 4 of them died in early infancy.[21] José María was born as the third son, but as his oldest brother perished and the second oldest became a religious,[22] it was him who inherited the family wealth.[23] Some sources suggest he received early education in the Salamanca Instituto General y Técnico,[24] others maintain that he frequented Seminario de Salamanca, then studied with “los jesuítas en Comillas”, and obtained bachillerato in the Jesuit Valladolid college[25] in or around 1905.[26] He then studied law in Valladolid[27] and graduated with excellent marks in 1909;[28] some sources mention also his agricultural education.[29]

In 1910[30] Lamamié married a local girl, Sofía Alonso Moreno (1887-1970);[31] she came from the local bourgeoisie family.[32] They settled at Lamamié family estate in the Salamanca province, in-between Alba de Tormes[33] and Babilafuente.[34] Though Lamamié is often referred in historiography as “rico ganadero y terrateniente”[35] or “grande terrateniente”[36] it is not clear what the actual size of his estates was. Various sources claim that the couple had 9[37] to 11[38] children. Raised in the very religious ambience,[39] at least 6 of them joined religious orders;[40] some served in America,[41] some grew to local prominence[42] and one son was killed as a requeté chaplain in 1937.[43] The family heir Tomás Lamamié de Clairac Alonso did not become a public figure, though he held high executive functions in SEAT and other companies.[44] Neither the Lamamié de Clairac Delgado nor the Liaño Pacheco Lamamié[45] grandchildren grew to prominence; the best known, Pilar Lamamié de Clairac Delgado, is a pediatrician.[46]

Early public activity

In 1904-1906 as a teenager Lamamié signed various open letters, usually protesting alleged official anti-Catholic measures[47] or publicly professing Christian faith.[48] He earned his name in history books already in 1908, when within a group of equally young 9 signatories – including Ángel Herrera Oria[49] - he co-founded Asociación Católica Nacional de Jóvenes Propagandistas,[50] later known as ACNDP.[51] Indeed, in 1909-1914 he engaged in Catholic propaganda, noted e.g. when speaking at local Catholic rallies,[52] entering committees which co-ordinated religious projects,[53] greeting bishops,[54] featuring prominently at local feasts[55] or contributing to El Salmantino daily.[56] Some of these engagements were increasingly flavored with “propaganda católico-social”.[57] Some time in the 1910s Lamamié left ACNDP, accusing them of "betraying the Catholic cause".[58]

In the early 1910s Lamamié opened his own law desk in Madrid, though little is known of its activity;[59] he remained active in the Salamanca family wheat business.[60] At that time he was already vice-president of the local branch of the Integrist organisation.[61] In the mid-1910s approaching the right-wing Maurista faction of the Conservatives,[62] in 1915 he decided to run on the Integrist ticket[63] to the town hall and was elected with no opposing candidate standing.[64] In the ayuntamiento he was counted among representatives of the extreme right and one of the most intelligent concejales at the same time.[65] As the only Integrist councilor he tended to alliance with Maurista, but also Jaimista members.[66] Press notes present him as an active and belligerent politician, concerned primarily with economic issues; given heavy debt burden of the city and financial problems ensuing,[67] in 1917 he supported governmental nomination of a new alcalde.[68] In the late 1910s Lamamié already presided over work of some municipal committees.[69] He was initially supposed to run for re-election; however, for reasons which remain unclear and were probably related to failed coalition talks[70] he withdrew from the race and ceased as concejal in 1920.[71]

Already in the late 1910s and thanks to his connections to Integrist parliamentarians like Manual Senante, Lamamié's proposals ended up at ministerial desks.[72] In 1918 he tried to enter nationwide politics himself; following in the footsteps of his father, he decided to run for the Cortes as an Integrist candidate from the district of Salamanca. In all boroughs he trashed the left-wing candidate Miguel de Unamuno, but by a slight margin he was himself defeated by a Liberal Romanonista candidate;[73] this did not prevent his supporters from claiming “triunfo moral”.[74] In the early elections called for 1919 Lamamié tried his hand again. Though he was known as councilor, local landowner, son to former deputy, Integrist, zealous Catholic propagandist and activist of local agrarian syndicates[75] he lost again; this time he was decisively defeated by a former military who ran as an independent Conservative candidate.[76] He was not noted as renewing his efforts in last elections of the Restoration era in the early 1920s;[77] he welcomed the 1923 Primo coup enthusiastically.[78]

In agricultural organisations

Already in 1918 Lamamié was vice-president of local Salmantine federation of agrarian syndicates.[79] After death of his father the following year he inherited most of the family estates and became “one of the largest landowners in the Salamanca district”.[80] Since the early 1920s he engaged heavily in works of local agricultural organisations; formally they posed as representing all rural stakeholders, but were usually dominated by landholders and adhered to the Catholic social doctrine. The key one was Federación Católica Agrícola,[81] renamed later to Federación Católico-Agraria Salmantina; rising to its president, since 1921 Lamamié represented the organization in the provincial Cámara Agricola.[82] In 1923 he rose beyond the province as he became one of the leaders of confederation of agrarian syndicates in the region of León;[83] in 1925 it evolved into Confederación Nacional Católico-Agraria de las Federaciones Castellano Leonesas.[84]

As representative of agrarian organizations he lobbied at various official administrative and self-governmental bodies, like Consejo Provincial de Fomento[85] and regional institutions;[86] already a recognized personality, at official feasts at times he spoke right after the civil governor.[87] In 1925 latest he was nominated comisario regio de fomento, a provincial delegate of Ministry of Infrastructure;[88] the same year he grew to president of Federación de Sindicatos Católicos.[89] In 1927 Lamamié was in executive of Unión Católico Agraria Castellano Leonesa; he tried to endorse its vision of rural regime[90] and took part in Congreso Nacional Cerealista;[91] also during following years he used to give lectures on organisation of agricultural labor.[92] In the late 1920s he focused on presidency of Federación Católico Agraria Salmantina and activity in Acción Social Católico Agraria.[93] He formed part of Comisíon Trigueroharinaria within Comisión Arbitral Agrícola, a primoderiverista arbitration committee supervised by Ministry of Agriculture,[94] and was member of Cámara de la Propiedad Rústica.[95] He grew to vice-president of Confederación Hidrográfica del Duero,[96] but scaled down his activity as a lawyer.[97]

Following the fall of Primo Lamamié assumed more militant political stand; in 1930 he agonized about “grave situation in agriculture”[98] and demanded permanent consultative representation of landowners’ federations in Madrid;[99] indeed he was shortly nominated member of Consejo del Economia Nacional.[100] On first pages he claimed that rural syndicates did not intend to engage in politics,[101] but on the other hand when representing “labrador castellano” they looked beyond purely agricultural interest.[102] In June he co-founded Acción Castellana,[103] supposed to promote “aspiraciones nacionales y agrarias”,[104] though he also appeared on meetings of Partido Provincial Agrario.[105] He called to do away with ruling corrupted oligarchies,[106] but opposed the rising republican tide by lambasting “false liberties and democratic absurdities”;[107] according to his vision, Castile as the heart of Spain remembered that “en primer término Dios”.[108] In September he declared running to the future Cortes in name of Sindicatos Católicos Agrarios,[109] but in February 1931 specified he would rather stand in name of Acción Castellana.[110] In April 1931 he was elected president of Confederación Nacional Católico-Agraria, the nationwide agricultural organization.[111]

Republic: in Cortes

As representative of Acción Castellana Lamamié joined a general right-wing alliance[112] and was comfortably elected to the first Republican Cortes from his Salamanca.[113] In the chamber he joined the Agrarian block;[114] with 2 other Integrists[115] he formed the right-wing[116] or “extreme right-wing” of the grouping.[117] As a Carlist he was re-elected from Salamanca[118] in 1933[119] and 1936; in the latter case the ticket was annulled[120] with his engagement in negotiation of government grain contracts quoted as incompatible with electoral law.[121] The 5 years spend in the Cortes marked the climax of Lamamié's career; though member of minor groupings, he became a nationally recognizable figure due to his oratory skills, vehemence and engagement in heated plenary debates. His parliamentary career was marked by two threads: opposition to republican agrarian policy and opposition to advanced secular format of the state.

Lamamié[122] “emerged as the most ardent Catholic opponent of state interference with the distribution of landed property”[123] and did his best to block the agrarian reform;[124] some count him among “defensores a ultranza de las viejas estructuras territoriales”.[125] Though Lamamié recognized the need to sanate the rural regime following “a century of rural liberalism”, he thought the republican law an over-reaction, “an even worse doctrine which converts us all into slaves of the state”.[126] Especially in 1933-1935 he labored to loosen already adopted rural regulations like the law on jurados mixtos or the Rural Lease Act.[127] Though he lambasted alleged etatisme of Giménez Fernández,[128] at times he swallowed his “dislike of state intervention” and demanded governmental assistance by purchases of wheat surplus.[129] Lamamié gained notoriety when left-wing newspapers quoted his declaration that he would turn a schismatic rather than accept land reform in case it gets supported by the Church;[130] the claim is referred in literature as a proof of Lamamié's hypocrisy,[131] but some claim it was fabricated by hostile propaganda.[132] The member of radical right-wing among the Agrarians, also among the Carlists he stood as “last-ditch defender of property”[133] against left-leaning party parliamentarians like Ginés Martinez Rubio.[134]

_15.jpg.webp)

Another major focus of Lamamié as a deputy were religious issues.[135] He vehemently supported confessionality of state and claimed that “God comes first, and not merely relegated to the privacy of conscience”.[136] During the constitutional debate of 1931 he ardently opposed stipulations he considered oppressive and unjust versus the Catholics,[137] warning that if the state turns against them, they “shall have no other remedy than to move against the Republic”.[138] Lamamié dedicated not one of his harangues to defend the Jesuits, the order marked for forcible dissolution; he tried to dismantle the republican narrative of the famous Jesuit “fourth vow”[139] and lambasted the draft not only as inhuman, but also as non-constitutional;[140] his campaign[141] lasted until 1933, but proved fruitless.[142] Numerous timed denied the right to speak,[143] he later got his parliamentary addresses published as a booklet.[144] During the 1933-1936 term, dominated by the Right, he demanded nothing less than derogation of the constitutional article which defined the Republic as a secular state.[145]

Republic: in Carlist executive

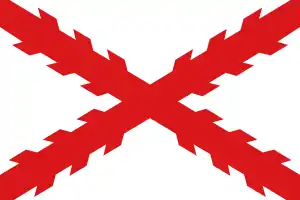

Lamamié entered the Republican parliament as an Integrist associated with Salamantine agrarian and generic right-wing circles,[146] but already in late 1931 he was at odds with local conservatives.[147] Instead, like most Integrists he started to approach the Carlists[148] and was leaning towards reunification of all Traditionalist branches.[149] The project was complete in early 1932, when they merged in Comunión Tradicionalista.[150] Within the organisation Lamamié entered its nationwide executive Junta Suprema and became secretary of the body;[151] he was also double-hatting as regional Traditionalist jefé in León.[152] In 1933 latest he was put in charge of the propaganda section[153] and reportedly contributed to change of Carlist image; the movement was no longer perceived as antiquated group of senile veterans but as a dynamic organization of young militants.[154] Though at times speaking at public rallies,[155] he turned into “the most persuasive and accomplished Carlist orator” in the Cortes.[156] He went well with older generation of leaders, especially the fellow landowner Rodezno, and following re-organisation of 1934 he entered not only the broad Junta Suprema Nacional, but also a much smaller governing body, Junta Delegada.[157]

Already in the early 1930s Lamamié worked with the fellow Integrist Manuel Fal[158] and reportedly claimed the latter would one day become the party leader.[159] Following growing disappointment with Rodezno's lead, in 1934 he and Manuel Senante floated the candidacy of Fal,[160] who indeed assumed the party jefatura. Under his command Lamamié retained his position as head of propaganda[161] and in 1935 was nominated to Council of the Communion, an advisory body supposed to assist Fal.[162] Since the mid-1930s he was gradually replacing Rodezno as the Carlist parliamentary leader. In the party he was one of the central figures who “could be relied upon to bridge the gap between the Communion old and new establishments”.[163]

Though some scholars admit that initially Lamamié might have been willing to collaborate with the Republican authorities,[164] adopted “una postura suave y conciliadora” and only after 1933 turned into “integrista furibundo”,[165] they note that it did not take long before he started to view the Republic as a tyrannical regime[166] to be toppled sooner or later.[167] He considered democracy incompatible with "people's rights".[168] Since late 1931 he was increasingly critical of right-wing politics guided by the “lesser evil” principle and hence abandoned Acción Castellana in late 1932.[169] Since then he scorned CEDA for illusions about rectifying the Republic[170] and in 1934 claimed that the CEDA-backed government[171] gave in to Lerroux and the Left.[172] In 1935 he engaged in virulent press polemics with his former protégé José María Gil-Robles[173] and was denounced by El Debate as running against the papal teaching;[174] in spite of it, in 1936 he half-heartedly assisted Fal in attempt to mount a right-wing electoral alliance.[175] While hostile to cedistas he was moderately[176] in favor of a generic monarchist alliance within National Bloque.[177] As former Integrist he was not outspoken on dynastical issues,[178] though he stayed fully within limits of the Carlist loyalty.[179]

Conspirator and rebel

Since the electoral triumph of Popular Front in February 1936 Lamamié was increasingly perplexed about perceived revolutionary tide and inclined towards mounting a counter-action. In the early spring he “nursed a longing for a purely Carlist rising”,[181] prepared but eventually abandoned by the Comunión executive. However, he remained heavily engaged in conspiracy;[182] together with dynastical representative Don Javier and Manuel Fal he formed a triumvirate which co-ordinated works of all sections of the organization.[183] Though he did not speak with military conspirators, he negotiated with Gil-Robles; as late as on July 12 in Saint-Jean-de-Luz the two fruitlessly discussed CEDA's access to the coup.[184] It is not clear where Lamamié resided on July 18–19, yet it is known that his wife and some sons remained in Madrid.[185]

On July 26 Lamamié delivered an address broadcast by the Burgos radio;[186] he called to support "sacrosant crusade" against "horde of evil-doers at the service of Russia".[187] In response his Madrid bank account was seized[188] and Republican press claimed a machine gun and loads of ammunition had been found in his safety deposit box.[189] During August he toured various cities in Northern Castile encouraging recruitment[190] and visiting requeté units.[191] In September he entered the newly formed wartime party executive Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra as its secretary.[192] With his office based in Burgos, Lamamié was also entrusted with recruitment and deployment of requeté.[193] He seemed to have stood in-between Fal Conde and somewhat autonomous Navarrese command, Junta Central Carlista. Some authors claim he was among Fal's less dependable trustees,[194] though this enabled him to engage in some fence-mending between the two Carlist Juntas.[195] When Fal was forced to go on exile the power in the party technically rested with Valiente and Lamamié, though in fact it slipped to traditional leaders from Navarre and the Vascongadas.[196] In December he was confirmed as member of the re-organized 8-member Junta Nacional.[197] He cultivated the usual propaganda tasks,[198] but was entrusted also with running Sección Administrativa.[199]

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

Lamamié was increasingly puzzled by the emerging Franco's heavy-handed rule. In early 1937 he intervened with general Dávila to get Fal Conde released from exile; the plea was to no avail.[200] In February he took part in the crucial Insua meeting, where Carlist leaders and their regent discussed the threat of military-imposed political amalgamation. His stand is not clear;[201] highly skeptical about forced unification, he did not voice decisively against it,[202] which did not spare him particular personal animadversion in the Franco headquarters.[203] One contemporary historian counts him among “two of the most persistent fence-sitters”[204] and another locates him “entre un polo y el otro” of the Carlist command layer. In early April he engaged in fruitless last-minute talks with Falangist leaders, staged to agree a bottom-up alliance.[205] Eventually when faced with the military unification dictate he grudgingly opted for compliance, assuming that in case something goes wrong, “our Sacred Cause would always be reborn out of its own ashes”.[206]

Restless sansidrino

Don Javier considered Lamamié fully loyal and authorized him to enter ruling bodies of the unificated state party,[207] but he preferred to tone down his political engagements. Instead, he resumed activity in agricultural organisations, in particular Confederación Nacional Católico Agraria, which he still presided. Because of its acronymic name CNCA, Lamamié and other of its top lobbyists were named "sansidrinos".[208] Already in June 1937 they staged a grand Asamblea Cerealista in Valladolid;[209] Lamamié was confirmed in presidency of CNCA and president of one of its components, Confederación Católico Agraria. Relations with the emerging Francoist regime remained correct; the traditional confederative structure was affiliated within the newly established national syndicalist Servicio Nacional de Trigo and both organizations declared total mutual understanding.[210] In late 1937 Lamamié personally obtained some unspecified contracts in the Salamanca province[211] and in March 1938 the Interior decree nominated him governor of the Burgos-based Banco de Crédito Local de España,[212] a bank entrusted with financial aid to municipalities taken over from the Republicans.[213]

Throughout 1938 CNCA and the national syndicalist Francoist administration were increasingly at a collision course, both advancing competitive visions of the rural regime.[214] The first battleground was Catalonia, where on areas seized by the Nationalists the traditional local body, Instituto Agricola Catalan de San Isidro, tried to reassert its domination. CNCA backed its claims and argued that they in no way interfered with officially declared vertical syndicates; a stalemate ensued.[215] However, in October 1938 the government issued Ley de Cooperativas, which left the sansidrinos profoundly disappointed. In April 1939 CNCA demanded that clear rules of the newly established Servicio Nacional de Cooperativas get published and underlined that traditional rural organizations did not enter SNC awaiting the moment it is legally defined. Lamamié issued declarations which in a veiled way warned against arbitrary ministerial decisions, advocated co-existence of state and private bodies, and called for recognition of 3-layer rural organizations.[216] During 1939 and 1940 CNCA claimed it could operate “sin rozar la función de los Sindicatos verticales”[217] and fought marginalization.[218]

In the early 1940s militant syndicalist Falangism enjoyed its climax in the Francoist Spain; it translated also into outcome of power struggle within the rural agricultural ambience. Despite repeated declarations of loyalty on part of CNCA and numerous assurances that in no way it posed a thread to syndical law,[219] conservative and Christian agrarians were getting increasingly pushed into the sidelines; also Lamamié lost steam and at one point admitted in relation to planned new regulations that “no tuvo ningún reparo que objetas sino por el contario le pareció muy bien”.[220] In September 1940 he left the CNCA presidency and declarations of their meeting with Delegación Nacional de Sindicatos sounded like admitting defeat.[221] With Lamamié as honorary president[222] CNCA was ultimately dissolved and incorporated into the new Unión Nacional de Cooperativas del Campo in 1942.[223] Lamamié kept presiding over Banco Exterior de Crédito Local de España at least until the early 1940s.[224]

Late Carlist activity

At the turn of the decades Lamamié was barely noted officially for Carlist political activity,[225] though he did participate in Traditionalism-flavored religious services or other rallies.[226] He used to take part in confidential meetings; in 1940 when returning from such a session with a carlo-francoist general Ricardo Rada he suffered a car accident[227] and barely managed to dispose of related potentially damaging documentation before the Guardia Civil patrol arrived.[228] The same year he corresponded with Director General de Seguridad protesting repressions against Carlist militants[229] in various provinces, e.g. in Ciudad Real, Salamanca, Murcia and Palma de Mallorca;[230] on another front, he conferred about keeping the Alfonsists in check.[231] In 1941 Lamamié supplied Don Javier with his political analysis, but its content is not known.[232] During the climax of the Nazi might in Europe he advocated a neutral Spanish policy[233] and declared that individual Carlists were free to enlist to División Azul, but Comuníon would in no way endorse the recruitment.[234] In another letter, sent 1942, he protested to Ramon Serrano Serrano against official measures applied to Fal Conde.[235] In 1943 he co-signed a large document addressed to Franco and known as Reclamación de Poder; its Carlist signatories called to do away with syndicalist features and to introduce a traditionalist monarchy.[236]

Though maintaining correct formal relations with official administration,[237] in the mid-1940s Lamamié counted among moderate anti-Francoists; during a 1944 monarchist gathering which included also the Alfonsists he voted against mounting a coup, intended to topple the caudillo.[238] In 1945 he participated in a clandestine San Sebastián meeting with Don Javier;[239] in 1947 he took part in the first session of Carlist executive since the 1937 Insua session and entered the re-established 5-member Consejo Nacional.[240] At times he published in semi-clandestine Carlist bulletings, though not under his own name.[241] In support of the moderately anti-Francoist falcondista strategy he opposed the vehemently anti-Francoist sivattista line, increasingly visible in the late 1940s.[242] In the early 1950s as secretary of the Carlist executive he prepared documentation supposed to back the royal claim of Don Javier, who until then had posed as a regent and did not advance explicit monarchical claims;[243] he edited the final version of the declaration, made by the claimant during the Eucharistic Congress in Barcelona in 1952.[244] At that time he was already suffering from bad health and in the early 1950s he used a wheelchair;[245] however, in 1954 he accepted membership in the renewed party Junta Nacional and its acting governing body Comisión Permanente.[246] In the mid-1950s the Carlist stand versus the regime changed from opposition to cautious co-operation; it was sealed by dismissal of Fal Conde and by José María Valiente assuming political leadership. The latter still considered Lamamié a loyal “hombre firme y enérgico”[247] and sounded him upon assuming secretariat of the ruling party junta. In 1956 Lamamié replied that though sick, he was ready to offer his name as “una garantía absoluta de defensa de la Causa”;[248] his death came earlier.

Footnotes

- La elegida como esposa: Eulalia Lamamié de Clairac Nicolaú, [in:] RamonSalasLarrazabal service 12.09.14, available at a WP-blocked WordPress service, 12.09.14; other sources claim the family came from Toulose, Etienne de La Mamye de Clairac entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- born 1646, died 1717, Etienne de La Mamye de Clairac entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- he is referred as “mariscal de campo” and “gobernador de Sant Omer (Flandes)”, Claudio Diego Jacobo Lamamye de Clairac entry, [in:] Familia Lamamie de Clairac blogspot 16.01.10, available here

- born 1703, died 1771; reportedly born in Toul near Meurthe-et-Moselle (Lorraine) he died in Huelva, Claudio Diego Jacobo Lamamye de Clairac entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- Claudio Diego Jacobo Lamamye de Clairac entry, [in:] Familia Lamamie de Clairac blogspot 16.01.10, available here

- born 1748, death date unknown, Miguel Lamamie de Clairac y Villalonga entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- Ramas Españolas II. Lamamie de Clairac – resumindo, [in:] Familia Lamamie de Clairac blogspot 06.01.10, available here

- born 1784, died 1847, Jose Ramon Lamamie de Clairac y Tirado entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- Antonio Luis López Martínez, Ganaderías de lidia y ganaderos: historia y economía de los toros de lidia en España, Sevilla 2002, ISBN 9788447207428, p. 152

- El Siglo Futuro 27.10.19, available here; some authors note him as ancestors as “allegedly “of French legitimist antecedents”, Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, p. 53. It is not clear what legitimism is mentioned, as the French ancestors arrived in Spain before the legitimist issue arose in France, while the Spanish ancestors engaged in legitimist cause were not French

- Juan Lamamie de Clairac y Trespalacios, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- “entre los principales terratenientes y ganaderos de la provincia”, Manuel María Urrutia León, Manuel María Urrutia, Miguel de Unamuno desconocido, Salamanca 2007, ISBN 9788478003846, p. 70

- he studied law in Salamanca; in the late 1860s he served as the Carlist subcomisario regio for Salamanca province and as provincial deputy in the 1870s; arrested in 1872, he was released on word of honor and got self-exiled to France. He returned in 1874, but in line with his pledge, did not engage in further conspiracy, El Siglo Futuro 27.10.19, available here

- Lamamié founded and managed La Tesis, La Tradición, La Región, La Información and El Salmantino; the first two he managed with Enrique Gil Robles and Manuel Sanchez Asensio

- as a wealthy terrateniente Lamamie was in position to buy votes of his “colonos”, Ros Ana Gutiérrez Lloret, Las elecciones de 1907 en Salamanca: un ejemplo de la movilización y confrontación electoral católica en la España de la Restauración, [in:] Studia Historica. Historia Contemporanea 22 (2004), p. 333

- see the official Cortes service, available here

- along Juan Olázabal, Javier Sanz Larumbe, Marqués de Casa Ulloa and Juan Balanzó y Pons, María Jesús Izquierdo, El Sexisme a la universitat: estudi comparatiu del personal assalariat de les universitats públiques catalanes, Barcelona 1999, ISBN 9788449015731, p. 98

- El Siglo Futuro 31.10.19, available here

- she was daughter to Luis Esteban de la Colina y González de la Riva and Felipa Fernández-Cavada y Espadero

- José María Lamamié de Clairas was short and of very meager posture; it is not clear whether it was anyhow related to advanced age of his father upon conception

- born between 1885 and 1894, Jacinto, María del Carmen, María de la Paz and María de las Dolores died before reaching the teen age, Jacinto Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here, Maria del Carmen Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here, María de las Dolores Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- Juan (1886-1963) served as a chaplain Cantabria, Juan Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- other surviving siblings identified were María Luisa (1883-1951), María Luisa Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here, and María de la Purísima (1892-1954), María de la Purisima Lamamie de Clairac y de la Colina entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available - here 5

- El Adelanto 20.06.05, available here

- Jesús Maldonado Jiménez, Actitudes político religiosas de la minoría agraria de las Cortes Constituyentes de 1931 [PhD Universidad Complutense 1974], Madrid 2015, p. 179

- El Salmantino 19.02.18, available here

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 179

- El Salmantino 09.10.09, available here

- El Salmantino 19.02.18, available here

- El Salmantino 02.04.10, available here

- Sofía Alonso Moreno entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- her father, Tomás Alonso del Moral, was the native of Valladolid. Tomas Alonso del Moral entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here. He was known as “conocido comerciante” and member of the local ayuntamiento and other bodies, El Fomento de Salamanca 31.01.98, available here. For her mother Aurea Moreno Brusi (1849-1937), the native of Salamanca, see Aurea Moreno Brusi entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- it seems that among many estates owned, the Lamamies resided on the one named “Martillán”, Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 59

- another location mentioned is San Cristóbal de Fuente, Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 59; it has not been identified. Another scholar claims that the Lamamie estates were located slightly elsewhere, namely in the Martillan county, Mary Vincent, Catholicism in the Second Republic: Religion and Politics in Salamanca, 1930-1936 [PhD thesis University of Oxford], Oxford 1991, p. 119

- José Andrés Gallego, Antón M. Pazos, Archivo Gomá: documentos de la Guerra Civil, vol. 9, Madrid 2001, ISBN 9788400084295, p. 411. Another scholar claims that in case of José María Lamamié the references to cattle-breeding are erroneous, see Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 179. Indeed, in the 1940s and 1950s fairly frequent press notes to toros de lidia coming from the Lamamie ganaderia referred to Leopoldo Lamamié de Clairac, Imperio 15.08.54, available here

- Ángel Bahamonde, 14 de abril. La República, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788401347764, p. 312

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 179

- Fallecimento Pe. Luis Lamamie de Clairac, [in:] Pjicohna blogspot 18.02.10, available here

- female children were educated by the Handmaids of the Sacred Heart, their five brothers went to the Jesuits in Madrid, Vincent 1991, p. 53; they were raised according to a very traditional model and address their father with the formal "usted", Vincent 1991, p. 268

- at least two daughters became nuns, María Luisa and María del Pilar, see Ma. Teresa Camarero-Nuñez, Mi nombre nuevo, Magnificat, Madrid 1961

- a Jesuit friar Luis died in Brazil, Fallecimento Pe. Luis Lamamie de Clairac, [in:] Pjicohna blogspot 18.02.10, available here; see also a YT homage to Luis, available here. Also a Jesuit friar Ignacio died in Mexico, Agradecimiento a Dios y a vosotros, [in:] Vallisoletana Dosmil 3 (2004), p. 3

- Juan (another Jesuit) was headmaster of the Salamanca seminary, Juan Lamamie de Clairac Alonso SJ, [in:] La Nueva España 28.04.16, available here

- José María Lamamie de Clairac (1911-1937) perished during fightings in Sierra de Guadarrama in February 1937, Hermanos Lamamié de Clairac y Alonso, Recuerdos de la guerra: España 1936-1939: vividos y relatados por los autores, México 1991, ISBN 9789688590317, p. 155, see also Ramón Grande del Brio, José María Lamamie de Clairac y Alonso entry, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- Ruth Whiteside (ed.), Major Financial Institutions of Europe 1994, London 1994, ISBN 9789401114608, p. 196

- Maria del Carmen Lamamie de Clairac Alonso entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here. For details on the Liaño Pacheco y Lamamié de Clairac offspring see Jaime de Salazar y Acha, Estudio histórico sobre una familia extremeña, los Sánchez Arjona, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788488833013, p. 531

- Dra Pilar Lamamie de Clairac Delgado, [in:] RuberInternacional service, available here

- El Labaro 04.06.06. available here

- El Siglo Futuro 28.07.04, available here; in 1905 Lamamié asked God to allow him to become “a genuinely Christian young man”, La Basilica Teresiana 15.09.05, available here

- José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen del primer catolicismo social español, [PhD thesis] Madrid 2012, p. 42

- the other 7 co-founders were Luis de Aristizábal, Jaime Chicharro, José Fernández de Henestrosa, Manuel Gómez Roldán, Angel Herrera Oria, José de Polanco and Gerardo Requejo, Luis Sánchez Movellán de la Riva, Cien años de la Asociación Católica, [in:] El Diario Montañes 10.12.09, available here

- Víctor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, La Iglesia que buscó la concordia, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788499206363, p. 66

- El Salmantino 03.04.09, available here, or El Salmantino 23.04.10, available here

- e.g. in 1910 he entered the local junta organizadora of the project to declare social sovereignty of Christ in Spain, El Salmantino 15.11.10, available here. The Lamamie estate hosted the first monument in Spain dedicated to Christ the King. By the 1930s it became the focus of annual processions, presided over by Jose Maria, Vincent 1991, p. 119

- El Adelanto 06.12.13, available here

- El Adelanto 23.02.14, available here

- El Salmantino 09.10.09, available here

- El Salmantino 17.05.12, available here

- the Lamamie family has even warned José María Gil-Robles against joining ACNDP, Vincent 1991, p. 153

- in 1913 Lamamié opened the law office in Madrid which was supposed to deal with “toda clase de asuntos de Derecho, especialmente civiles, y a testamentarias”, La Victoria 13.12.13, available here

- e.g. in 1912 Lamamié enlarged family holdings by new purchases, El Salmantino 04.12.12, available here

- El Salmantino 12.01.11, available here

- e.g. during the 1915 elections Lamamié supported a Maurista candidate, Libertad 22.03.15, available here

- El Adelanto 19.11.15, available here; at times he was reported as a maurista, El Adelanto 18.10.15, available here

- El Adelanto 15.11.15, available here

- El Adelanto 11.08.16, available here

- El Salmantino 04.05.17, available here

- El Adelanto 21.04.17, available here

- El Adelanto 16.03.17, available here

- e.g. in 1917 Lamamie presiding over electoral works to renew composition of the ayuntamiento in partial elections, El Salmantino 22.12.17, available here

- El Adelanto 07.02.20, available here

- El Adelanto 09.01.20, available here

- El Salmantino 19.06.18, available here

- Lamamié gathered 4,900 votes, while his opponent collected 5,200 votes, El Adelanto 26.02.8, available here, see also El Adelanto 25.02.18, available here

- El Salmantino 08.03.18, available here, also El Salmantino 11.03.18, available here

- El Salmantino 18.02.18, available here

- El Adelanto 02.06.19, available here

- one scholar claims that "Lamamie de Clairac had himself been sufficiently involved with the 'old' politics to be returned to the Cortes as a deputy for the city of Salamanca just before Primo's coup in May 1923", Vincent 1991, p. 180; it is not clear what is meant here

- Vincent 1991, p. 181; the author quotes Lamamie's interview to El Debate of October 1923

- El Salmantino 19.02.18, available here

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 57; also “wealthy, locally powerful stockbreeder and landlord” - Blinkhorn 2008, p. 53. The information about stockbreeding is incorrect

- El Adelanto 01.03.20, available here

- El Adelanto 28.11.21, available here, for 1923 see El Adelanto 17.04.23, available here

- La Correspondencia de España 18.10.23, available here

- Boletín de Acción Social órgano de la Federación Católico-Agraria Salmantina y de las instituciones promovidas por la Junta Diocesana de Acción Catolica-Social 4 (1925), available here

- El Adelanto 01.10.20, available here

- La Victoria 19.07.24, available here

- La Victoria 10.10.25, available here

- El Adelanto 16.12.25, available here; Lamamie served as comisario regio de fomento and head of Consejo Provincial de Fomento at least until 1928, El Adelanto 24.01.28, available here

- El Adelanto 16.12.25, available here

- it included regulation of rental contracts and advanced a theory named “socialismo agrario”, El Día de Palencia 09.02.27, available here

- El Adelanto 06.09.27, available here, also Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 60

- El Adelanto 19.10.29, available here

- El Día de Palencia 26.05.28, available here

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 180

- Boletín de Acción Social órgano de la Federación Católico-Agraria Salmantina y de las instituciones promovidas por la Junta Diocesana de Acción Catolica-Social 11 (1929), available here. One scholar claims that "Proprietors of Rural Estates" organization - not sure whether same as Cámara de la Propiedad Rústica - was founded "in response to the Republic's plans for agrarian reform", Vincent 1991, p. 167

- Diario de Burgos 31.01.29, available here; the company was active at least since 1926, El Adelanto 19.12.26, available here

- in 1928 Lamamie ceased as member of Junta de Gobierno of the Salamanca colegio de abogados, El Adelanto 25.05.28, available here

- El Día de Palencia 02.05.30, available here

- El Dia de Palencia 14.04.30, available here

- Las Provincias 16.12.30, available here

- Vincent 1991, p. 183

- El Dia de Palencia 13.05.30, available here; for another huge front-page interview see El Dia de Palencia 30.05.30, available here

- its flag was that of the fatherland and "Religion, Family, Order, Property and Monarchy" slogan, Vincent 1991, p. 179

- Miróbriga 29.06.30, available here

- El Dia de Palencia 10.10.30, available here

- one scholar claims Lamamie was part of the primoderiverista oligarchy himself as Salamanca's representative "in the dictator's National Assembly", Vincent 1991, p. 181. There is no confirmation of his place in the Asamblea Nacional Consultiva, and the official Cortes service does not list him (or any other Lamamie) as such

- in March 1931 Lamamié demanded also derogation of penal code adopted during the dictatorship, El Adelanto 05.03.31, available here

- Jaume Claret Miranda, Esta salvaje pesadilla: Salamanca en la Guerra Civil Española, Salamanca 2007, ISBN 9788484329015, p. 9

- Heraldo Alaves 06.09.30, available here

- El Adelanto 13.02.31, available here

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 180

- Acción Castellano was a satellite of Acción Nacional, the latter generally dominated by the Alfonsinos and accidentalists; Integrist presence in the organisation was a bit of an exception, Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 50; similar comments in Vincent 1991, p. 191

- see the official Cortes service, available here

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 126; one author claims that the Agrarian block "distilled old monarchist wine into new republican bottles", Vincent 1991, p. 221

- dubbed “integrist trio”; its other members were Estévanez Rodríguez and Gómez Roji, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 56

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 189

- Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 217

- initially Lamamie was supposed to run in the 1933 elections from Barcelona, Robert Vallverdú i Martí, El carlisme català durant la Segona República Espanyola 1931-1936, Barcelona 2008, ISBN 9788478260805, p. 146

- see the official Cortes service, available here

- Vallverdu i Martí 2008, p. 289; see also the official Cortes service, available here

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 231

- allegedly with José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones, Lamamie was one of “dos personajes de enorme relevancia en el campo político conservador” in the province; Blinkhorn 2008, p. 65

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 65

- Francisco Javier Lambán Montañés, La reforma agraria republicana en Aragón, 1931-1936 [PhD Universidad de Zaragoza], Zaragoza 2014, p. 74

- opinion of Manuel Tuñon de Lara, Objectivo: acabar con la República, [in:] SBHAC service, available here

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 79

- Sergio Riesco Roche, La lucha por la tierra: reformismo agrario y cuestión yuntera en la provincia de Cáceres [PhD thesis Complutense], Madrid 2005, p. 340

- Lamamié vehemently opposed cutting down minimum prices of wheat and blamed speculators, not producers, for high market prices

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 195

- his alleged statement which made rounds across all Spain was that “si not quitan las tierras, nos haremos cismáticos”; another version is that when told that "habría que poner en marcha medidas en el agro que siguieran la doctrina social de la Iglesia", Lamamié replied that "antes se hacía cismático", both versions repeated after Lambán Montañés 2014

- Lambán Montañés 2014, p. 74

- Víctor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, „Si nos quitan las tierras, not haremos cismáticos”, [in:] Pregón 53 (2019), pp. 34-35

- though Lamamie is usually presented as fierce opponent of Republican agrarian reform, he was equally hostile versus the rural regime as endorsed by syndicalist revolutionaries of the Falange, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 124

- Gínes Martínez is presented with some irony – perhaps aimed to question sincerity of his zeal – as “proletarian hammer of the selfish capitalist”, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 124. One scholar claims, however, that politicians like Lamamie "posed effectively as the true defenders of the people", Vincent 1991, p. 355

- the Lamamie family was zealously Catholic. During the Republic days, when religious public rallies were generally illegal save for specific permits, on the private Lamamie estate they organized pilgrimages and romerias, at times attracting thousands of attendees, Vincent 1991, p. 134. The author mentions a "Juan Lamamie" as organizer

- “lo primero es Dios, pero no relegado a la intimidad de la conciencia, como ahora es modo sostener, sino a quien no concebimos sino informandolo todo: el individuo, la familia, la sociedad, las costumbres, las leyes, la moral y el derecho”, quoted after Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 270

- "within the Cortes and such unlikely champions of democracy as Lamamie de Clairac and Gil-Robles, together with their fell ow Agrarians, the priest-deputies Gomez Rojf and Molina Nieto, were to be heard speaking the language of liberty, equality and civil rights", Vincent 1991, pp. 239-240

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 66, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 54. Reportedly that was "at the instigation of Lamamie" that the Agrarians, the Traditionalists and the Basques withdrew from the Cortes in protest during voting on the constitutional draft, Vincent 1991, p. 242

- Lamamie claimed that only some 25% of the Jesuits took the famous “fourth vow” of obedience to the pope, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 78

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 61

- reinforced by La Gaceta Regional, a Salamanca daily purchased in 1932 by a consortium of local businessmen, led by Lamamie, Vincent 1991, p. 156

- in May 1933 Lamamie unleashed his fury against the draft of the Law on Congregations; he declared it as aimed against God and openly claimed that it should be disobeyed, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 104

- e.g. in 1932 the speaker did not allow Lamamie to take to the floor and speak in defence of the Jesuits. He found an unexpected ally in the person of Miguel de Unamuno, who came to his help and claimed he had the right to speak, Alfonso Carlos Saiz Valdivielso, Don Miguel de Unamuno, un disidente ante las Cortes Constituyentes de la Segunda República, [in:] Estudios de Deusto 51/1 (2003), p. 333

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 62

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 180

- e.g. during the 1931 electoral campaign he toured the Salamanca province with José María Gil-Robles, then rather unknown aspiring right-wing politician, Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 100

- already in November 1931 Lamamié was at odds with local conservatives; despite his position of the local parliamentarian he did not speak at their rallies. Background of the conflict is not entirely clear; apart from controversies related to reportedly appeasing conservative stand versus the Republic there might have been personal issues involved, Maldonado Jiménez 2015, p. 53

- one scholar names Lamamie "lifelong supporter of the Carlist pretender to the throne", Vincent 1991, p. 180. However, there is no information available on his support for the Carlist claim prior to 1931

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 73

- it seems that though member of the Carlist organization, until dissolution of the Cortes in 1933 he used to form part of the Agrarian minority, Vincent 1991, p. 234

- Moral Roncal 2009, pp. 77-78

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 79

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 70

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 83

- despite his role in the Carlist nationwide executive Lamamié fairly rarely spoke on public rallies beyond his native Old Castile; one of such cases was the spring 1932 campaign in Catalonia, Vallverdu i Marti 2008, p. 101, César Alcalá, D. Mauricio de Sivatte. Una biografía política (1901-1980), Barcelona 2001, ISBN 8493109797, p. 20

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 78

- Junta Delegada consisted of Rodezno, Pradera, Lamamié and Oriol, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 133, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 117

- [Ana Marín Fidalgo, Manuel M. Burgueño], In memoriam. Manuel J. Fal Conde (1894-1975), Sevilla 1978, p. 25

- Pensamiento Alaves 25.01.38, available here

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 137

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 207, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 120; in line with his propaganda tasks, in 1935 co-ordinated activities of the Carlist press, Vallverdu i Martí 2008, p. 275

- the Council consisted of Bilbao, Larramendi, Alier, Senante and Lamamie, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 215, Vallverdu i Martí 2008, p. 263

- Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 229-230

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 60

- J. M. Castells, Las asociaciones religiosas en la España contemporanea, Madrid 1973, p. 394

- in the aftermath of sanurjada and in midsts of ensuing governmental repressions Lamamié “was typical in belabouring the government for stepping up its ‘tyrannical’ behaviour by means of indiscriminate arrests, suspensions, closures, expropriations and deportations”, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 93

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 66, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 54

- "la democracia política es la negación efectiva de los derechos del pueblo", quoted after María Concepción Marcos del Olmo, Cultura de la violencia y Parlamento: los diputados Castellanos y Leoneses en las Cortes de 1936, [in:] Diacronie 7 (2011), p. 9

- Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 101-102

- Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 129-130

- in late 1932 and early 1933 Lamamié declared that Carlism would never collaborate with any republican government, this is neither with a right-wing one, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 103

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 187. During the tenure of the right-wing government Lamamie was fully aware and approving of few Carlist militants being sent to Rome to receive military training with a view of a future violent overthrow of the Republic, Vincent 1991, p. 297

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 192

- Moral Roncal 2009, p. 153

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 203

- in 1933 Lamamie was not very enthusiastic about a close co-operation with Renovación Española; if so, it was to serve very limtied, pragmatic, electoral ends and in no way should it amount to any firm alliance, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 109

- historiographic accounts tend to differ. One scholar counts Lamamié among farily enthusiastic supporters of Bloque Nacional, see Blinkhorn 2008, p. 189; others are less definite, see Moral Roncal 2009, p. 125

- e.g. in 1931 the Traditionalists were bewildered about a so-called Pact of Territet, an informal dynastical agreement allegedly sealed by Alfonso XIII and Don Jaime; it is difficult to tell from the accounts available what the position of Lamamié was, Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 72, 322

- one of the rare cases when Lamamié engaged in dynastical propaganda during the Republc era was his co-edition of a 1935 document, signed by a few Carlist leaders. Following the wedding of the Alfonsist infant Don Juan, the document denied any rights to the throne either to Don Juan or to his future offspring, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 208

- blown up by a grenade during fightings in Sierra de Guadarrama in February 1937. Four months earlier, his father called upon the young men to "sacrifice your lives on the altar of ... traditional Spain", quoted after Vincent 1991, pp. 348-349

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 238

- Vallverdu i Martí 2008, p. 296, Jordi Canal, El carlismo. Dos siglos de contrarrevolución en España, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788420639475, p. 324

- Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 8487863523, p. 19; Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936-1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709758, p. 99

- Aróstegui 2013, p. 117

- Lamamié’s wife and children trapped in Madrid following some time found refuge in foreign diplomatic missions and eventually made it to the Nationalist zone; for recollections of verious members of the Lamamié de Clairac family, including these residing in Madrid, see Lamamié de Clairac y Alonso 1991, pp. 19-101

- Heraldo de Zamora 27.07.36, available here

- Vincent 1991, p. 343, though it is not sure whether the phrases quoted were not broadcast during a later, August Lamamie speech

- La Libertad 20.08.36, available here

- Heraldo de Castellón 20.08.36, available here

- Pensamiento Alaves 08.08.36, available here

- Aróstegui 2013, p. 632

- Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 22

- Aróstegui 2013, p. 647

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 269

- e.g. in early December 1936, following Fal Conde’s decision to set a Carlist-only military academy, Lamamié travalled to Pamplona to discuss with the local executive the details of setting up and the institution and organizing its teaching staff; one historian views the move as sort of an olive branch offered to the Navarrese Junta by Fal and the central Junta, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 237

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 278

- it consisted of Fal Conde, Rodezno, Lamamié, Valiente, Sáenz-Díez, Muñoz Aguilar, Arauz de Robles and Zamanillo, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 241

- see e.g. his 1937 appearance in Palencia, El Día de Palencia 07.01.37, available here, or in Zamora, Imperio 08.02.37, available here

- the Carlist executive was territorially dispersed; in late 1936 and early 1937 Lamamié and his Sección Administrativa were based in Burgos; Fal Conde and his collaborators were based in Toledo; Rodezno and Sección Política resided in Salamanca, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 238

- Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 243

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 283, Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 46

- Peñas Bernaldo 1996, pp. 257, 263

- in early 1937 particular “animadversación” in the Franco’s headquarters was directed at Lamamié, Zamanillo and Araiz de Robles, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 267

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 287; the other one was allegedly Arauz de Robles

- Fidaldo, Burgueño 1980, p. 43, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 269

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 291

- Blinkhorn 2008, p. 293

- Javier Tébar Hurtado, Contrarrevolución y poder agrario en el franquismo. Rupturas y continuidades. La provincia de Barcelona (1939-1945), [PhD thesis Universidad Autonoma], Barcelona 2005, p. 115

- El Adelanto 23.06.37, available here

- La Espiga 05.11.37, available here

- El Adelanto 26.11.37, available here

- some authors claim that already in 1919 Lamamie was president of "the local [Salamanca] savings bank", Vincent 1991, p. 165

- Heraldo de Zamora 21.03.38, available here

- already during the Republican period Lamamié voiced against fascism, which he equalled to a state dictate; he lambasted it as an imported theory not applicable to Spain, even though he saw some of its features – like “emphasis upon hierarchy and combativeness” – appropriate for Carlist paramilitary units, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 166

- Tébar Hurtado 2005, pp. 112-113

- the 3-layer structure recommended by Lamamié was to consist of 1) Sindicatos (to become Cooperativas), 2) Federaciones, and 3) nationaiwde Confederación. His declarations of the time contained a hardly veiled criticism of Falangist syndicalism, compare La Espiga 06.05.39, available here

- El Dia de Palencia 30.04.39, available here

- e.g. a CNCA document of October 1939 referred to earlier Francoist legislation on cooperatives, adopted on November 29, 1938, and in line with the January 28, 1906 legislation attempted to carve out a space within the rural regime where Catholic syndicated might operate, La Espiga 28.10.39, available here

- La Espiga 10.04.40, available here

- Tébar Hurtado 2005, p. 186

- El Progreso 06.09.40, available here

- La Espiga 24.12.42, available here

- Emilio Majuelo, Falangistas y católico-sociales en liza por el control de las cooperativas, [in:] Historia del presente 3 (2004), p. 39

- Heraldo de Zamora 17.02.40, available here; as late as in 1943 he was involved in dealings of the Salamanca ayuntamiento, but it is not clear whether he formed part of it, El Adelanto 18.12.43, available here

- he was moderately engaged in Nationalist propaganda work, e.g. following takeover of Catalonia in 1939 he embarked on a tour there, Pensamiento Alaves 21.01.39, available here

- e.g. in August 1939 with some other Traditionalist militants – notably his fellow ex-Integrist Senante – he took part in religious service to employees of Editorial Tradicionalista who perished ruring the war, Labór 28.08.39, available here

- Manuel de Santa Cruz [Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta], Apuntes y documentos para la historia del tradicionalismo español: 1939-1966, vols. 1-3, Seville 1979, p. 95

- Heraldo de Zamora 26.01.40, available here

- Santa Cruz 1979, p. 95

- Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936-1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, p. 148

- Santa Cruz 1979, p. 26

- Santa Cruz 1979, p. 82

- in a 1941 letter to Serrano Suñer Lamamié quoted the case of Carlos VII, who assumed a neutral stand during the international 1898 crisis, and this of Jaime III, who advocated neutrality during the First World War

- Santa Cruz 1979, pp. 137-140

- Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 92

- Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 96, Alcalá 2001, p. 52

- e.g. he kept exploitining his personal links to get Carlists out of detention centers, Miralles Climent 2018, p. 169

- Alcalá 2001, p. 57

- Miralles Climent 2018, pp. 276, 397

- the Council consisted of Fal Conde, Valiente, Zamanillo, Saenz-Diez and Lamamié, Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 106, Canal 2000, p. 350

- Miralles Climent 2018, p. 293

- Alcalá 2001, pp. 72, 78

- Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 132

- Jacek Bartyzel, Nic bez Boga, nic wbrew tradycji, Radzymin 2015, ISBN 9788360748732, p. 251

- Nueva Alcarría 24.07.54, available here

- Vallverdu i Martí 2014, p. 138

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, pp. 40-41

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del carlismo hacia la colaboración con el régimen (1955-56), [in:] Hispania 69 (2009), pp. 190-191

Further reading

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349

- Hermanos Lamamié de Clairac y Alonso, Recuerdos de la guerra: España 1936-1939: vividos y relatados por los autores, México 1991, ISBN 9789688590317

- Jesús Maldonado Jiménez, Actitudes político religiosas de la minoría agraria de las Cortes Constituyentes de 1931 [PhD Universidad Complutense 1974], Madrid 2015

- Emilio Majuelo Gil, Falangistas y católicos sociales en liza por el control de las cooperativas, [in:] Historia del presente 3 (2004), pp. 29–43

- Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054

- Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 8487863523

- Antonio Pérez de Olaguer, Piedras Vivas. Biografia del Capellan Requete Jose M. Lamamie de Clairac y Alonso, Madrid 1939

- Mary Vincent, Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic: Religion and Politics in Salamanca, 1930-1936, London 1996, ISBN 9780198206132