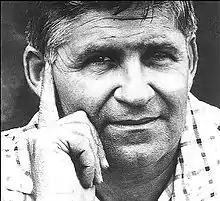

John Howard Griffin

John Howard Griffin (June 16, 1920 – September 9, 1980) was an American journalist and author from Texas who wrote about racial equality. He is best known for his project to temporarily pass as a black man and journey through the Deep South of 1959 to see life and segregation from the other side of the color line. He first published a series of articles on his experience in Sepia Magazine, which had underwritten the project. He published a fuller account in a book Black Like Me (1961). This was later adapted as a 1964 film of the same name. A 50th anniversary edition of the book was published in 2011 by Wings Press.[1]

John Howard Griffin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 16, 1920 |

| Died | September 9, 1980 (aged 60) Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Education | University of Poitiers |

| Occupation | Writer |

Notable credit(s) | Black Like Me |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Ann Holland

(m. 1953; |

| Children | 4 |

Early life

Griffin was born in 1920 in Dallas, Texas, to John Walter Griffin and Lena May Young.[2] His mother was a classical pianist, and Griffin acquired his love of music from her. Awarded a musical scholarship, he went to France to study French language and literature at the University of Poitiers and medicine at the École de Médecine. At 19, he joined the French Resistance as a medic, working at the Atlantic seaport of Saint-Nazaire, where he helped smuggle Austrian Jews to safety and freedom in England.[3]

Griffin returned to the United States and enlisted, serving 39 months in the United States Army Air Corps stationed in the South Pacific, during which he was decorated for bravery. He spent 1943–44 as the only European-American on Nuni, one of the Solomon Islands, where he was assigned to study the local culture. He suffered a bout with spinal malaria that left him temporarily paraplegic.[3] During this year, Griffin married an island woman.[2] In 1946 he suffered an accident which temporarily blinded him.

He returned home to Texas without his wife and converted to Roman Catholicism in 1952, becoming a Lay Carmelite. He taught piano. He gained dispensation from the Vatican for a second marriage. He married one of his students, Elizabeth Ann Holland, and they had four children.

In 1952, he published his first novel, The Devil Rides Outside, a mystery set in a monastery in postwar France, where a young American composer goes to study Gregorian chant.[4]

During the 1940s and 1950s, Griffin wrote a number of essays about his loss of sight and his life, followed by his spontaneous return of sight in 1957.[5] At that point he began to develop as a photographer.

He published Nuni (1956), a semi-autobiographical novel drawing from his year "marooned" in the Solomon Islands. It shows his developing interest in ethnography. He conducted a kind of social study in his 1959 project, resulting in his book Black Like Me (1961).[3]

Black Like Me and later

In the fall of 1959, Griffin decided to investigate firsthand the plight of African Americans in the South, where racial segregation was legal; blacks had been disenfranchised since the turn of the century and closed out of the political system, and whites were struggling to maintain dominance against an increasing civil rights movement.

Griffin consulted a New Orleans dermatologist for aid in darkening his skin, being treated with a course of drugs, sunlamp treatments, and skin creams. Griffin shaved his head in order to hide his straight hair. He spent weeks travelling as a black man in New Orleans and parts of Mississippi (with side trips to South Carolina and Georgia), getting around mainly by bus and by hitchhiking. He was later accompanied by a photographer who documented the trip, and the project was underwritten by Sepia magazine, in exchange for first publication rights for the articles he planned to write. These were published under the title Journey into Shame.

Griffin published an expanded version of his project as Black Like Me (1961), which became a best seller in 1961. He described in detail the problems an African American encountered in the segregated Deep South meeting the needs for food, shelter, and toilet and other sanitary facilities. Griffin also described the hatred he often felt from white Southerners he encountered in his daily life—shop clerks, ticket sellers, bus drivers, and others. He was particularly shocked by the curiosity white men displayed about his sexual life. He also included anecdotes about white Southerners who were friendly and helpful.[3]

The wide publicity about the book made Griffin a national celebrity for a time. The book had several editions. In a 1975 essay included in later editions of the book, Griffin recalled encountering hostility and threats to him and his family in his hometown of Mansfield, Texas. Someone hanged his figure in effigy. He eventually moved his family to Mexico for about nine months before they returned to Fort Worth.[3][6]

The book was adapted as a 1964 film of the same name, starring James Whitmore as Griffin, and featuring Roscoe Lee Browne, Clifton James and Will Geer. A 50th anniversary edition of the book was published in 2011 by Wings Press.[1]

The author continued to lecture and write on race relations and social justice during the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1964, Griffin received the Pacem in Terris Award from the Davenport (Iowa) Catholic Interracial Council for his contributions to racial understanding. In 1975, Griffin was severely beaten by the Ku Klux Klan, but survived.[7]

In his later years, Griffin focused on researching his friend Thomas Merton, an American Trappist monk and spiritual writer whom he first met in 1962. Griffin was chosen by Merton's estate to write the authorized biography of Merton, but his health (he had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes) prevented him from completing this project. He concentrated on Merton's later years.

Posthumous works

Griffin's nearly finished portion of the biography, which covered Merton's later years, was posthumously published in paperback by Latitude Press in 1983 as Follow the Ecstasy: Thomas Merton, the Hermitage Years, 1965–1968.[8]

Griffin's essays about his blindness and recovery were collected and published posthumously as Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision (2004).[9]

In recognition of the 50th anniversary of the publication of Black Like Me, Wings Press published a new edition. It also published updated editions of Griffin's other works, including his first novel, Devil Outside the Walls.

Death

Griffin died in Fort Worth, Texas, on September 9, 1980, at the age of 60, from complications of diabetes.[10] He was survived by his wife Elizabeth Ann Griffin and children. He was buried in the cemetery in his birthplace of Mansfield, Texas. After her death, Elizabeth was also buried there, although she had remarried.

There have been persistent rumors that Griffin died of skin cancer, which purportedly developed from his use of large doses of methoxsalen (Oxsoralen) in 1959 to darken his skin for his race project. Griffin did not have skin cancer but he did experience temporary and minor symptoms from taking the drug, especially fatigue and nausea.[10]

Related works

- Robert Bonazzi wrote a biographical memoir of Griffin: Man in the Mirror: John Howard Griffin and the Story of Black Like Me (1997). Bonazzi had published other works by Griffin at his Latitudes Press. In 2012 Bonazzi was said to be working on full-scale biography of Griffin, with the working title Reluctant Activist: The Authorized Biography of John Howard Griffin. It is being edited at Texas Christian University by intern Hayley Zablotsky.[11]

- Uncommon Vision: The Life and Times of John Howard Griffin is a film documentary released in 2011 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his influential book. Directed and produced by Morgan Atkinson, it was aired on PBS stations. The film is also included as an extra on the 2013 DVD release of the film Black Like Me.[11]

Works

- The Devil Rides Outside (1952)

- Nuni (1956)

- Land of the High Sky (1959)

- Black Like Me (1961)

- The Church and the Black Man (1969)

- A Hidden Wholeness: The Visual World of Thomas Merton (1970)

- Twelve Photographic Portraits (1973)

- Jacques Maritain: Homage in Words and Pictures (1974)

- A Time to be Human (1977)

- The Hermitage Journals: A Diary Kept While Working on the Biography of Thomas Merton (1981)

- Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision (2004), posthumous collection of essays from the 1940s and 1950s

- Available Light: Exile in Mexico (2008) Autobiographic texts of the period he writes the essay 'black like me'

See also

- Ray Sprigle, a white journalist, disguised himself as black and travelled in the Deep South with John Wesley Dobbs, a guide from the NAACP. Sprigle wrote a series of articles under the title I Was a Negro in the South for 30 Days. The articles formed the basis of Sprigle's 1949 book In the Land of Jim Crow.

- Grace Halsell, a white female journalist, also Texan, who, inspired by Griffin, disguised herself as black in a similar manner. Shortly after the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., she left her position on President Lyndon B. Johnson's White House staff for the journey she described as "embracing the Other". She published her account the next year as Soul Sister: The Story of a White Woman Who Turned Herself Black and Went to Live and Work in Harlem and Mississippi. She undertook many similar immersive disguises throughout her career.

- Günter Wallraff, a white German undercover journalist who often immersed himself in parts to reveal the treatment of others (an alcoholic, a worker in a chemicals factory, a homeless person), and released the 2009 documentary Black on White, showing how he was treated in Germany while undercover as a black man.

References

- Sarfraz Manzoor, "Rereading: Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin", The Guardian, 27 October 2011, accessed 2 May 2016

- Article about Griffin, tshaonline.org; accessed October 5, 2015.

- Kevin Connolly (October 25, 2009), Exposing the colour of prejudice, BBC News

- Enda McAteer, "Review: 'The Devil Rides Outside' ", 23 March 2014, Catholic Fiction website, accessed 2 May 2016

- Focus Newman, University of New Mexico, Vol. 8, No. 1, October 1964.

- Jonathan Yardley (March 17, 2007), "John Howard Griffin Took Race All the Way to the Finish", Washington Post

- http://www.novelguide.com/black-like-me/biography

- John Howard Griffin, Follow the Ecstasy: Thomas Merton, the Hermitage Years, 1965–1968, ed. Robert Bonazzi, Latitude Press, 1983

- Sue Ann Gardner, "Review of Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision by John Howard Griffin;" Orbis, 2004, MultiCultural Review (Spring 2005) v. 14, no. 1: 71–72

- "Dispute of the belief that Griffin died from his skin darkening treatments true", Snopes.com

- "DVD Release: Black Like Me", retrieved 2-13-2013.

Further reading

- Crossing the Line: Racial Passing in Twentieth-century U.S. Literature and Culture by Gayle Wald. Duke University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8223-2515-2.

External links

- "A Revolutionary Writer", John H. Griffin

- Full-view books about John H. Griffin at Google Book Search

- John Howard Griffin Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- John Howard Griffin speaking at the 1962 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards as broadcast on WNYC, April 11, 1962.