Joaquin Murrieta

Joaquin Murrieta Carrillo (sometimes spelled Murieta or Murietta) (1829 – July 25, 1853), also called The Robin Hood of the West or the Robin Hood of El Dorado, was a figure of disputed historicity associated with the novel The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit by John Rollin Ridge and subsequent legends about a famous outlaw in California during the California Gold Rush of the 1850s. Evidence for a historical Joaquin is scarce. Contemporary documents record testimony concerning a minor horse thief by the same name in 1852. Bandidos with the name 'Joaquin' involved in the robbery and murder of several Chinese were reported by newspapers during the same time. A California Ranger by the name of Harry Love was tasked with and eventually brought in a human head claimed to be that of Murieta.[2]

Joaquin Murrieta | |

|---|---|

Artist's portrayal of Murrieta | |

| Born | 1829 Sonora, Mexico |

| Died | July 25, 1853 (aged 23–24) |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Other names | The Robin Hood of El Dorado, The Mexican Robin Hood |

| Occupation | Vaquero, Gold miner, outlaw |

| Known for | Outlaw leader during time period of California Gold Rush |

| Spouse(s) | Rosa Feliz aka Rosita Carmela or Rosita Carmel Feliz |

| Parent(s) | Joaquin and Rosalia (née Carillo) Murrieta |

| Relatives | Jesus Murrieta (elder brother), Antonio Murrieta (brother), Rosa Murrieta (niece), Herminia Murrieta (niece), Anita Murrieta (niece), Ramon Feliz (Father-in-law),[1] Procopio (nephew) |

The popular legend of Joaquin Murrieta was that he was a Sonoran forty-niner, a vaquero and a gold miner and peace-loving man driven to seek revenge when he and his brother were falsely accused of stealing a mule. His brother was hanged and Joaquin horsewhipped. His young wife was gang raped and in one version she died in Joaquin's arms. Swearing revenge, Joaquin hunted down all who had violated his sweetheart. He embarked on a short but violent career that brought death to his Anglo tormentors. The state of California then offered a reward of up to $5,000 for Joaquin "dead or alive." He was reportedly killed in 1853, but the news of his death were disputed and myths later formed about him and his possible survival.

In 1919, Johnston McCulley supposedly received his inspiration for his fictional character Don Diego de la Vega—better known as Zorro—from the 1854 book entitled The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit by John Rollin Ridge. John heard about a Mexican miner who had turned to banditry and was intrigued by the story.[3][4]

Controversy over his life

Controversy surrounds the figure of Joaquin Murrieta: who he was, what he did, and many of his life's events. This is summarized by the words of historian Susan Lee Johnson:

"So many tales have grown up around Murrieta that it is hard to disentangle the fabulous from the factual. There seems to be a consensus that Anglos drove him from a rich mining claim, and that, in rapid succession, his wife was raped, his half-brother lynched, and Murrieta himself horse-whipped. He may have worked as a monte dealer for a time; then, according to whichever version one accepts, he became either a horse trader and occasional horse thief, or a bandit."[5]

John Rollin Ridge, grandson of the Cherokee leader Major Ridge, wrote a dime novel about Murrieta; the fictional biography contributed to his legend, especially as it was translated into various European languages. A portion of Ridge's novel was reprinted in 1858 in the California Police Gazette. This story was picked up and subsequently translated into French. The French version was translated into Spanish by Roberto Hyenne, who took Ridge's original story and changed every "Mexican" reference to "Chilean".

Early life and education

Most biographical sources hold that Murrieta was born in Hermosillo[5] in the northwestern state of Sonora, Mexico. The historian Frank Forrest Latta, in his twentieth-century book Joaquín Murrieta and His Horse Gangs (1980), wrote based on his decades of investigations of the Murrieta family in Sonora, California and Texas, that Joaquin Murrieta was from the Pueblo de Murrieta on the Rancho Tapizuelas, across the Cuchujaqui River, (known locally as the Arroyo de Álamos), to the north of Casanate, in the southeast of Sonora, near the Sinaloa border, within what is now the Álamos Municipality, of Sonora.[6]:127,153 He was educated at a school nearby in El Salado.[6]:199

1849 Migration to California

Murrieta reportedly went to California in 1849 to seek his fortune in the California Gold Rush.[5] His older Carrillo stepbrother Joaquin Carrillo, who was already in California wrote back about the 1848 gold discovery and told Joaquin to come to California. Like many Sonorans, Murrieta and a party including his new wife Rosa Feliz, came to California across the Altar and Colorado Deserts in 1849. This party included Joaquin's younger brother (Jesus Murrieta), Jesus Carrillo Murrieta his other Carrillo stepbrother, three Feliz brothers-in-law (Claudio, Reyes and Jesus), two Murrieta cousins (Joaquin Juan and Martin Murrieta), four Valenzuela cousins (including Joaquin Theodoro and Jesus Valenzuela), two Duarte cousins (Antonio and Manuel Duarte), and a few other men from Pueblo de Murrieta or nearby.[6]:2,101,105–6,126–129,133–140

Five Joaquins Gang

Joaquín Murrieta encountered prejudice and hostility in the extreme competition of the rough mining camps. While mining for gold, he and his wife supposedly were attacked by American miners jealous of his success.[5] They allegedly beat him and raped his wife. However, the source for these events is not considered reliable, as it was a dime novel, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, written by John Rollin Ridge and published in 1854.[5]

Latta wrote that Joaquín Murrieta's gang had well organized bands, one led by himself and the rest led by one or two of his Sonoran relatives that he had grown up with. Latta documented that the core of these men had first gathered to help Murrieta kill at least six of the Americans who had summarily hanged his stepbrother Jesus Carrillo and whipped him on the false charge of the theft of a mule. They then regularly engaged in illegal horse trade with Mexico, with stolen horses and legally captured mustangs, driving them from as far north as Contra Costa County and from the gold camps of the Sierras and from the Central Valley via the remote La Vereda del Monte trail through the Diablo Range then south to Sonora for sale.[6]:77–143

Bands of his gang when not engaged in the horse trade robbed and killed miners or settlers, particularly those returning from the California goldfields.[7][8] The gang is believed to have killed up to 28 Chinese and 13 Anglo-Americans.[9] This figure only takes account of the reports from their raids in early 1853.

By 1853, the California state legislature considered Murrieta enough of a criminal menace to list him as one of the so-called "Five Joaquins" on a bill passed in May 1853. The legislature authorized hiring for three months a company of 20 California Rangers, veterans of the Mexican–American War, to hunt down "the five Joaquins, whose names are Joaquin Muriati [sic], Joaquin Ocomorenia, Joaquin Valenzuela, Joaquin Botellier, and Joaquin Carillo, and their banded associates."[10] On May 11, 1853, the governor John Bigler signed an act to create the "California State Rangers," to be led by Captain Harry Love (a former Texas Ranger and Mexican War veteran).

The state paid the California Rangers $150 a month, and promised them a $1,000 governor's reward if they captured the wanted men. On July 25, 1853, a group of Rangers encountered a band of armed Mexican men near Arroyo de Cantua on the edge of the Diablo Range near Coalinga, California. In the confrontation, three of the Mexicans were killed. They claimed one was Murrieta, and another Manuel Garcia, also known as Three-Fingered Jack, one of his most notorious associates.[8] Two others were captured.[11] A plaque (California Historical Landmark #344) near Coalinga at the intersection of State Routes 33 and 198 now marks the approximate site of the incident.

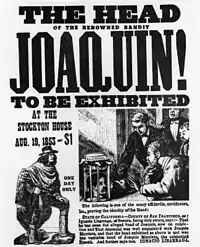

As proof of the outlaws' deaths, the Rangers cut off Three-Fingered Jack's hand, and the alleged Murrieta's head, and preserved them in a jar of alcohol to bring to the authorities for their reward.[5][8] Officials displayed the jar in Mariposa County, Stockton, and San Francisco. The Rangers took the display throughout California; spectators could pay $1 to see the relics. Seventeen people, including a Catholic priest, signed affidavits identifying the head as Murrieta's, alias Carrillo.

Love and his Rangers received the $1,000 reward money. In August 1853, an anonymous Los Angeles-based man wrote to the San Francisco Alta California Daily that Love and his Rangers murdered some innocent Mexican mustang catchers, and bribed people to swear out affidavits.[12] Later that fall, California newspapers carried letters by a few men claiming that Capt. Love had failed to display Murrieta's head at the mining camps, but this was not true.[13] On May 28, 1854, the California State Legislature voted to reward the Rangers with another $5,000 for their defeat of Murrieta and his band.[14]

But, 25 years later, the myths began to form. In 1879, O. P. Stidger was reported to have heard Murrieta's sister say that the displayed head was not her brother's.[15] At around the same time, numerous sightings were reported of Murrieta as a middle aged man. These were never confirmed. His preserved head was destroyed during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire.

Murrieta's nephew, known as Procopio, became one of California's most notorious bandits of the 1860s and 1870s; he purportedly wanted to exceed the reputation of his uncle.

The Real Zorro

Murrieta was possibly partly the inspiration for the fictional character of Zorro, the lead character in the five-part serial story, "The Curse of Capistrano", written by Johnston McCulley, and published in 1919 in a pulp fiction magazine.

For some activists, Murrieta had come to symbolize the resistance against Anglo-American economic and cultural domination in California. The "Association of Descendants of Joaquin Murrieta" says that Murrieta was not a "gringo eater," but "He wanted to retrieve the part of Mexico that was lost at that time in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo."[16]

Representations in media

Joaquin Murrieta has been a widely used romantic figure in novels, stories, comics and films, and on TV.

Literature:

• “Trail Of Vengeance” (1977) by Louis Kretschman. Historical fiction depicting the life of Joaquin Murrieta and his band of avengers.

- The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta (1854) by John Rollin Ridge, published one year after Murieta's supposed death. Parts of this were translated into French and Spanish, adding to his legend in Europe.

- Burns, Walter Noble (1932). The Robin Hood of El Dorado. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc.

- Yellow Bird (John Rolin Ridge), The Life and Adventures of JOAQUIN MURIETA, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1955. With introduction by Joseph Henry Jackson, a reprint of the only known copy of the 1854 original book by John Rolin Ridge.

- Fulgor y Muerte de Joaquín Murieta, (tr. The Splendor and Death of Joaquin Murieta by Ben Belitt) – a play by the Chilean Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda, published in English in paperback in 1972.

- L'Homme aux Mains de Cuir (The Man with the Leather Hands) by French writer Robert Gaillard, published in 1963 [17]

- Daughter of Fortune, a 1999 novel by Isabel Allende, includes the mythical figure of Murrieta.

- Звезда и смерть Хоакина Мурьеты (Zvezda i smert' Khoakina Mur'ety – The Star and Death of Joaquin Murieta), 1976, opera by Alexei Rybnikov and Pavel Grushko, is based on Pablo Neruda's play.

- Bandit's Moon, (1998) by Sid Fleischman, an award-winning children's novel.

- L.A. Outlaws, a 2008 novel by T. Jefferson Parker, and another of Parker's 'Charlie Hood' series of novels, feature Murietta as an ancestor of some of the main characters.

- "The History & Adventures of the Bandit Joaquin Murietta" (2012[18]) a novella by Stanley Moss (b. 1948), retelling the legend of the outlaw intertwined with a memoir

- "This is a Suit" – a slam poem by Joaquin Zihuatanejo.

- "The California Trail" by Ralph Compton, a small part in chapters 22 and 23

Film, Radio, and TV:

- The Robin Hood of El Dorado, 1936 film by William A. Wellman with Warner Baxter in the leading role.[19]

- Family Theater radio program, June 21, 1950 broadcast, "Joaquin Murietta" with Ricardo Montalbán as the title character.

- The Bandit Queen, 1950 film by William Berke with Phillip Reed as Murrieta.[20]

- The Adventures of Kit Carson, 1951 series television premiere episode, "California Bandits", with Rico Alaniz as Murrietta.

- Stories of the Century, 1954 television series, episode "Joaquin Murrieta" with Rick Jason in the starring role

- Death Valley Days, long running television and radio Western anthology series, episodes "I Am Joaquin" (1955) with Cliff Fields (credited as Field) as Murrieta; and "Eagle in the Rocks" (1960) with Ricardo Montalban playing Murrieta.

- The Last Rebel a 1958 Mexican film with Carlos Thompson as Murrieta.[21]

- The Firebrand a 1962 film with Valentin de Vargas as Murrieta.[22]

- Murieta, a 1965 Spanish Western directed by George Sherman with Jeffrey Hunter as Murrieta.[23]

- The Big Valley, United States ABC TV Series, 1967, episode "Joaquin" with Fabrizio Mioni as Juan Molina, suspected to be Joaquin Murrieta

- Desperate Mission, United States Television Movie, 1969, with Ricardo Montalban as Joaquin Murrieta

- The Star and Death of Joaquin Murieta, a 1982 Soviet musical drama film with Andrey Kharitonov as Murrieta.

- The Mask of Zorro (1998 film) features a youthful Joaquin Murrieta and his death at the hands of Captain Harrison Love (A Fictionalized version of Murrieta's real killer Harry Love). Joaquin's fictional brother Alejandro (Antonio Banderas) assumes the role of Zorro, and kills Love in revenge. Victor Rivers played Joaquin and Matt Letscher played Capt. Love.

- Murrieta is referenced in CSI S05E12 "Snakes" by a suspect claiming to be his descendant and therefore protected by him.

- Behind The Mask of Zorro (2005) a History Channel documentary about Murrieta and how he inspired the character of Zorro.

- Faces of Death II, 1981 fake documentary film about death. Murrieta's head in the jar was believed to have survived the earthquake, and was sold to different collectors; its current "owner" has it on display, and explains the legend.

- The Head of Joaquin Murrieta, (2015) PBS short-documentary. As producer John Valadez seeks the head of Murrieta, and seeks to bury it.

- Timeless, (2018) in the first half of the two-part series finale "The Miracle of Christmas". Murrieta is played by Paul Lincoln Alayo.[24]

- The Man Behind the Gun, (1953 film) Murrieta aids an undercover army officer fight insurrectionists who want Southern California to secede and become a slave state in 1850s Los Angeles. Robert Cabal as Joaquin Murrieta

Comics:

- Joaquin Murrieta in Desperado #2, Lev Gleason, Aug 1948, art by Dan Barry

- In 1950, Joaquin Murietta appears on comic strip Casey Ruggles by Warren Tufts.

- Death to Gringos! in Jesse James #7, Avon Periodicals, May 1952, art by Howard Larsen

- The California Terror! in Badmen of the West #2 [A-1 #120], Magazine Enterprises, 1954

- The Fabled Killer-Caballero Of California in Western True Crime #4, Fox Feature Syndicate, Feb 1949

Music:

- "Así Como Hoy Matan Negros," recorded by Víctor Jara and Inti-illimani, based on Pablo Neruda and Sergio Ortega's collaboration Fulgor y Muerte de Joaquín Murieta.

- "Cueca de Joaquín Murieta" recorded by both Víctor Jara and Quilapayún, in the style of Chile's national dance, the cueca - the song is featured on the album X Vietnam

- "Premonición de la Muerte de Joaquin Murieta" (Premonition of the death of Joaquin Murieta), a tribute to Murrieta, performed by Quilapayún - the song is featured on the album Quilapayun Chante Neruda

- "The Ballad of Joaquin Murrieta", performed by the Sons of the San Joaquin on the album Way Out Yonder.

- "The Bandit Joaquin" recorded by Dave Stamey

- "Murieta's Last Ride" and "Rosita", recorded by Beat Circus on the album These Wicked Things

- "Murrietta's Head" written and recorded by Dave Alvin on the album Eleven Eleven

- "Joaquin Murietta" by Spectra Paris

- "Joaquin Murrieta, 1853" by Bob Frank & John Murry

- "Corrido de Joaquin Murrieta" by Los Alegres de Terán

- "Stella Ireland and Lady Luck" by American folk singer/songwriter/guitarist Debby McClatchy

- "Adios Querrida" recorded by Wayne Austin on the album "By the Old San Joaquin"

- "The Star and Death of Joaquin Murieta", a 1976 rock opera by Alexey Rybnikov, based on "Fulgor y muerte de Joaquín Murieta" by Pablo Neruda.

- "Del Gato" recorded by Gene Clark and Carla Olson, from the album So Rebellious a Lover, 1987, written by Gene Clark/Rick Clark

- "La Leyenda de Joaquin Murieta" ballet by Jose Luis Dominguez (Chilean composer/conductor). Released by Naxos Records in 2016.

- "Fulgor y muerte de Joaquín Murieta" recorded by Olga Manzano and Manuel Picón, based on Pablo Neruda, in 1974.

_page_1.jpg.webp) Joaquin Murrieta (Aug 1948), art by Dan Barry.

Joaquin Murrieta (Aug 1948), art by Dan Barry. Death to Gringos! (May 1952), art by Howard Larsen.

Death to Gringos! (May 1952), art by Howard Larsen.

In the late twentieth century a Los Angeles, California Chicano community center was named "Centro Joaquin Murrieta de Aztlan."[25]

References

- Burns, Walter Noble, The Robin Hood of El Dorado Coward-McCann, Inc., New York, 1932.

- Gordon, Thomas (1983). Joaquin Murieta: Fact, Fiction, and Folkore (Masters). Utah State University, Logan.

- "The Real Zorro, Unmasked". Desert Magazine. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17.

- "El Bandito Joaquin Murrieta". Desert Magazine.

- Frank F. Latta, JOAQUIN MURRIETA AND HIS HORSE GANGS, Bear State Books, Santa Cruz, California. 1980. xv,685 pages. Illustrated with numerous photos. Index. Photographic front endpapers.

- Frank F. Latta's uncle may have been one of their victims. Samuel N. Latta disappeared and was never heard from again. He disappeared after writing a letter to his wife and daughters from Robinson's Ferry saying he had sold his gold claim and in a few days was going out to Stockton and San Francisco for his trip home to Arkansas with $8,000 in gold. Latta, JOAQUIN MURRIETA, p.43

- Ron Erskine (5 Mar 2004). "Joaquin Murrieta slept here". Morgan Hill Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 24 Oct 2016.

- Peter Mancall; Benjamin Heber-Johnson (2007). Making of the American West: People and Perspectives. p. 270. ISBN 9781851097630.

- The Statutes of California passed at the Fourth Session of the Legislature, George Kerr, State Printer, 1853, p.194 An Act to Create a Company of Rangers

- "California State Rangers". California State Military Museum. 1940. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- Alta California, August 23, 1853, p.2, The Head of Joaquin Murieta not Taken - A Strange Story

- Democratic State Journal, Oct. 17, 1853, Calaveras Correspondence from W. C. P. of Mokelumne Hill; San Joaquin Republican, Oct. 20, 1853, correspondence from Sonora, Tuolumne Co.

- WPA, "California State Rangers: History", 1940, California State Military Museum, accessed 7 August 2011

- See The Pioneer, Sat., Nov. 29, 1879. Also see History of Nevada County (Oakland : Thompson & West, 1880; rprt Berkeley: Howell-North Books, 1970), 115.

- Bacon, David (December 15, 2001). "Interview with Antonio Rivera Murrieta". Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- http://booknode.com/l_homme_aux_mains_de_cuir_0339972

- Amazon eBook ASIN: B00ATYKW3C

- Nugent, Frank S. (14 March 1936). "Concerning, Among Others, 'Robin Hood of El Dorado,' at the Capitol, and 'Love Before Breakfast.'". NY Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Nevins, Francis M.; Keller, Gary D. (2008). The Cisco Kid: American Hero, Hispanic Roots. Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe. p. 68. ISBN 9781931010498.

- Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1985). The Motion Picture Guide. 5. Cinebooks. p. 1618. ISBN 9780933997059.

- Keller, Gary D. (1994). Hispanics and United States Film: An Overview and Handbook. Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe. p. 155. ISBN 9780927534406.

- Green, Paul (9 April 2014). Jeffrey Hunter: The Film, Television, Radio and Stage Performances. McFarland Publishing. pp. 112, 114. ISBN 9780786478682.

- Holmes, Martin (20 December 2018). "'Timeless' Returns to Say Goodbye in an Emotional Series Finale (RECAP)". TV Insider. NTVB Media, Inc. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Blaine, John; Baker, Decia, eds. (1973). "Neighborhood Arts Centers". Community Arts of Los Angeles (Report). Los Angeles Community Art Alliance. p. 21. hdl:10139/2728. OCLC 912321031.

Media

- The Big Valley Season 3, Episode 1. First aired September 11, 1967

- "The Man Behind The Gun' 1953, with Randolph Scott, Murrieta was played by Robert Cabal

Further reading

- Yellow Bird (John Rolin Ridge), The Life and Adventures of JOAQUIN MURIETA, University of Oaklahoma Press, Norman, 1955. With introduction by Joseph Henry Jackson, a reprint of the only known copy of the 1854 original book by John Rolin Ridge.

- Ridge, John Rolin, The Life and Adventures of JOAQUIN MURIETA the Celebrated California Bandit. Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged by the Author, F. MacCRELLISH & CO., San Francisco, 1874. Joaquin Murrieta, pp. 3–40.

- Jackson, Joseph Henry, BAD COMPANY, The Story of California's Legendary and Actual Stage-Robbers, Bandits, Highwaymen, and Outlaws, from the Fifties to the Eighties. Reprint of the first edition, published in 1939. Bison Books, 1977.

- Frank F. Latta, Joaquin Murrieta and His Horse Gangs, Bear State Books, Santa Cruz, California. 1980. xv,685 pages. Illustrated with numerous photos. Index. Photographic front endpapers.

- Varley, James F., The Legend of Joaquin Murrieta, California,s Gold Rush Bandit, Big Lost River Press, Twin Falls, ID, 1995. Includes the California Gazette, February 21, 1852, Confession of Teodor Vasquez in Appendix A.

- Paz, Ireneo (1904). Vida y Aventuras del Mas Celebre Bandido Sonorense, Joaquin Murrieta: Sus Grandes Proezas En California (in Spanish) (English translation by Francis P. Belle, Regan Pub. Corp., Chicago, 1925. Republished with introduction and additional translation by Luis Leal as Life and Adventures of the Celebrated Bandit Joaquin Murrieta: His Exploits in the State of California, Arte Publico Press, 1999. ed.). Mexico City.

- John Boessenecker, Gold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes, Wiley, 1999.

- Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush. New York: W. W. Norton. 2000. ISBN 978-0-393-32099-2.

- Seacrest, William B., The Man From The Rio Grande: A Biography of Harry Love, Leader of the California Rangers who tracked down Joaquin Murrieta, The Arthur H. Clark Company, Spokane, 2005. Includes a very extensive account of the outlaws career including many quotes drawn from period news sources and personal accounts.

- Wilson, Lori Lee, The Joaquin Band, The History behind the Legend, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2011.

- Iddings, Ray, Joaquin Murrieta, The True Story from News Reports of the Period, Create Space, 2016. Includes military reports and news reports from 1846 - 1931.

External links

- Joaquín Murrieta, Picacho

- The Legend of Joaquin Murieta

- "Mystery of the decapitated Joaquin", Benicia News

- "Joaquin Murrieta", Biographic Notes, Inn-California

- Jill L. Cossley-Batt, The Last of the California Rangers (1928

- "What's the story on Joaquin Murieta, the Robin Hood of California?", Straight Dope

- American Mythmaker: Walter Noble Burns and the Legends of Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, and Joaquín Murrieta, by Mark J. Dworkin, University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.