Izapa

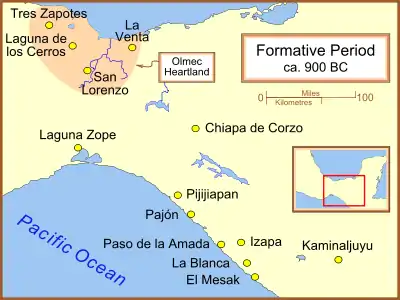

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it is best known for its occupation during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, near the base of the volcano Tacaná, the sixth tallest mountain in Mexico.

The settlement at Izapa extended over 1.4 miles, making it the largest site in Chiapas. The site reached its apogee between 850 BCE and 100 BCE; several archaeologists have theorized that Izapa may have been settled as early as 1500 BCE, making it as old as the Olmec sites of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La Venta.[1][2] Izapa remained occupied through the Early Postclassic period, until approximately 1200 CE.

Due to the abundance of carved Maya stelae and monuments at Izapa, the term "Izapan style" is used to describe similarly executed works throughout the Pacific foothills and highlands beyond, including some found at Takalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu.[3]

Izapa is located on wet and hilly land made of volcanic soil; it is still fertile for agriculture. The weather is very hot and very wet. The area around Izapa was a major cacao producing area known as the Soconusco region, which was used by the Aztecs.

Site layout and architecture

Izapa was a large site that included extensive monuments and architecture. From north to south, the whole site is about 1.5 km long. The New World Archaeological Foundation project at Izapa mapped 161 total mounds. Izapa's Formative period core (850–100 BCE) has six major plazas. Groups A, B, C, D, G, and H are located around the central area of the site, on the western shore of River Izapa.[4] "The core area of Izapa is formed by Groups A to E, G and H, which correspond to the period of the greatest apogee of the site, circa 300 B.C. to 50 B.C. "[5] Group F, is located at northern end of the site. This group contains a ballcourt among other structures, and corresponds to the late occupational phase of the site. Group F includes later occupation and construction associated with the Terminal Formative (100 BCE – 250 CE), Early Classic (250–500 CE), Middle Classic (500–700 CE), Late Classic (700–900 CE), and Early Postclassic (900–1200 CE) periods. Groups A, B, and F are open for tourism today through Mexico's National Institute for Anthropology and History (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia).

Izapa's architecture makes up roughly 250,000 cubic meters when combined. The site included pyramids, sculptured plazas and squares, and possibly two ball courts. There are two long open areas that resemble ball courts found at other Mesoamerican sites, but it is unclear if these two courts were used for the ballgame. Mound 30A was where a stepped pyramid was built. This pyramid was around ten meters high and probably used for religious and ceremonial purposes.

Izapa is laid out just east of true north; the exact alignment is 21 degrees east of north.[6] It is aligned with the volcano Tacaná and also seems to be situated to the December solstice horizon.

Izapa and other Mesoamerican civilizations

Michael Coe describes Izapa as being a connective link between the Olmec and the early Maya. He supports his argument with the large amount of Olmec style motifs used in Izapan art, including jaguar motifs, downturned human mouths, St. Andrew's Cross, flame eyebrows, scrolling skies and clouds, and baby-face figurines. Also used to support Coe's hypothesis are elements in Maya culture thought to be derived from the Izapans, including similarities in art and architecture styles, continuity between Maya and Izapan monuments, and shared deities.

Other archaeologists argue that there is not yet enough known to support Coe and that the term "Izapan Style" should only be used when describing art from Izapa. Virginia Smith argues that Izapan art is too unique and different in style to be the result of Olmec influence or the precursor to Maya art. Smith says that Izapan art is very site specific and did not spread far from the site. Izapan art most likely did indirectly influence Maya art, though it would just be one of the many influences on the Maya.

Izapa is also included in the debate of the origin of the 260-day calendar. The calendar was originally thought to be a Maya invention, but recently it has been hypothesized that calendar originated in Izapa.[7] This hypothesis is supported by the fact that Izapa fits the geological and historical conditions better than the previous place thought to be the origin.

Izapan monumental art

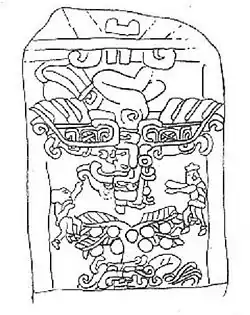

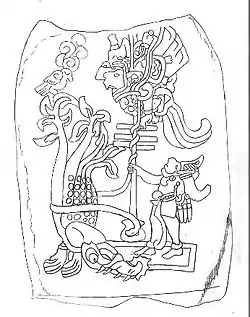

Izapa gains its fame through its art style. The art found at the site includes sculptures of stelae and also altars that look like frogs. The stelae and frog altars generally went together, the toads symbolized rain. There are common characteristics of Izapan art, such as winged objects, long-lipped gods much like the Chaac of the Maya,[8] Olmec-like swirling sky and clouds, feline mouth used as frame, representation of animals (crocodile, jaguar, frog, fish, birds), overlapping, and lack of dates.

The sheer number of sculptures outweighs that of any contemporaneous site. Garth Norman has counted 89 stelae, 61 altars, 3 thrones, and 68 "miscellaneous monuments at Izapa. In contrast to the ruler-oriented sculpture of the Epi-Olmec culture 330 miles (550 km) across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Izapan sculpture has features mythological and religious subjects, and is ceremonial and frequently narrative in nature.[9]

Also, in contrast to Epi-Olmec and later Maya stela, Izapa monuments rarely contain glyphs. Although this could imply that the Izapan culture lacked knowledge of any writing system, Julia Guernsey, author of a definitive work on Izapa sculpture, proposes instead that the monuments were intentionally language-free and that "Izapa's position at the juncture of two linguistic regions [i.e. Mixe–Zoque and Maya] may have fostered the penchant for non-verbal communicative strategies."[10] Timothy Laughton, a British researcher, has provided a reading of the imagery and narrative depictions as one unified mythological whole, linking the mythology with the distribution of the monuments at the site.

Among the possible Izapa glyphs discussed by scholars are some that are known as “U Shape”, “Border Panel” (skyband), and “Crossed Band”. These glyphs have parallels with known Olmec symbols.[11]

Notable monuments

Izapa Stela 1 features a long lipped deity, which Coe describes as the early version of Maya god of lightning and rain, Chaac. In Stela I, the god is walking on water while collecting fish into a basket and also wearing a basket of water on his back.

Izapa Stela 2, like Stela 25, has been linked to the battle of the Maya Hero Twins against Vucub Caquix, a powerful ruling bird-demon of the Maya underworld, also known as Seven Macaw.

Izapa Stela 3 shows a deity wielding a club. This deity's leg turns into a serpent while twisting around his body. This could be an early form of the Maya God K, who carried a staff.

Izapa Stela 4 depicts a bird dance, which has a king being transformed into a bird. The scene is most likely connected with the Principle Bird Deity. This transformation could symbolize shamanism and ecstasy, meaning the shaman-ruler used hallucinogens to journey to another world. The type of political system that was in place at Izapa is still unknown, though Stela 4 could suggest that a shaman was in charge. This shaman-ruler would serve the role of both the political and religious leader.

Izapa Stela 5 presents perhaps the most complex relief at Izapa. Central to the image is a large tree, which is surrounded by perhaps a dozen human figures and scores of other images. The complexity of the imagery has led some fringe researchers, particularly Mormon and "out of Africa" theorists, to view Stela 5 as support for their theories.

Izapa Stela 8 shows a ruler seated on a throne, which is located within a quatrefoil. The scene shown on Stela 8 is often compared to Throne 1, which was located by the central pillar of Izapa. Stela 8 may be showing a ruler seated atop Throne 1.

"When considered as a conceptual unit, the imagery of Throne 1 and Stela 8 directly associates the ruler's political authority, symbolised by the throne, with his supernatural abilities, symbolised by the quatrefoil portal (Guernsey 2006). A striking parallel exists between the imagery of Chalcatzingo Monument 1 and Izapa Stela 8, both of which feature elite individuals enthroned within a quatrefoil."[12]

Izapa Stela 21 is a rare depiction of violence involving deities. The Stela illustrates a warrior holding the head of a decapitated god.

Izapa Stela 25 possibly contains a scene from the Popol Vuh. The image depicted on Stela 25 is most likely the Maya Hero Twins shooting a perched Principle Bird Deity with a blowgun. This scene is also shown on the Maya pot called the "Blowgunner Pot". It is also suggested that Stela 25 could be seen as a map of the night sky, which was used to tell the story of the Hero Twins shooting the bird deity.

Archaeological research at Izapa

Early Investigations

Early investigators were drawn to research at Izapa by the site's large mounds and many carved monuments. Drawings of the monuments at Izapa were first published in a pamphlet by Mexican professor Carlos A. Culebro.[13] Karl Ruppert visited the site in 1938 while working with the Carnegie Institution.[14] In 1941, Matthew Stirling working on behalf of the National Geographic and the Smithsonian Institution conducted a week of excavations at Izapa to better reveal some of the carved monuments.[14] In a 1947, Philip Drucker expanded on Stirling's work with an additional series of small-scale test excavations.[15] Notes and photographs from Drucker's expedition are housed in the National Anthropological Archives.

Excavations by the New World Archaeological Foundation

From 1961 to 1965 Gareth Lowe directed four seasons of excavations at Izapa as behalf of the New World Archaeological Foundation (an organization run out of Brigham Young University).[16] The NWAF excavations emphasized the discovery of monuments and understanding the construction history of Izapa's central plazas. As part of this project, Eduardo Martínez also developed the first detailed map of the site.[17]

Lowe and colleagues dated the majority of Izapa's monuments to the Guillen phase, from approximately 300 to 50 BCE, on the basis of ceramic and radiocarbon dates, associating them with Izapa's period of greatest sculptural and construction activity. Izapa's earliest mound, Mound 30 was among the areas most extensively studied by the NWAF was first constructed during the Middle Formative Duende phase, c. 900–850 BCE.[18][17]

Excavations by Hernando Gómez Rueda

After a hiatus of 25 years, excavations resumed at Izapa under the direction of Hernando Gómez Rueda, working for Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). Gómez Rueda spent four seasons at Izapa from 1992–1996 with the primary goal of documenting Izapa's hydraulic system and monuments. Gómez Rueda suggested several possible roles for Izapa's hydraulic system, including distribution of water throughout the site, pools for raising edible aquatic species, and a hybrid ceremonial-functional use.[19]

Izapa Regional Settlement Project

Beginning in 2011, the Izapa Regional Settlement Project (IRSP) became the first project to investigate Izapa from a regional settlement perspective. Over four seasons of survey between 2011 and 2015 director Robert Rosenswig, a professor at the University at Albany, and his team used lidar (light detection and ranging) to map sites and collect surface ceramics to document changing population trends at Izapa and nearby areas.[20][21] Reports generated from this remapping suggest that the Formative period center of Izapa was actually twice as large as was understood from the previous map and that the Classic period occupation was nearly three times as large as was indicated by the original NWAF map.[20][22] The lidar map further illustrated an E-Group architectural alignment and terracing in the site center that had not been visible from the earlier NWAF map.[20]

Izapa Household Archaeology Project

In 2014, Rebecca Mendelsohn directed a new series of excavations at the southern edge of the site. Mendelsohn's project, the Izapa Household Archaeology Project, sought to document daily life of Izapa's residents. This project contributed the first systematic economic data for the site. Mendelsohn's research focuses on the period between 100 BCE – 400 CE when monument production declined, and major changes in construction activity, burial practices, and ritual activities were recorded for the site.[23]

Replica of a gravestone from Izapa, Chiapas located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaques translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Bas relief from Izapa depicting a person loading something."

Replica of a gravestone from Izapa, Chiapas located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaques translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Bas relief from Izapa depicting a person loading something." Replica of gravestone located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaque translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan Culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Original is from Izapa, Chiapas. Represents a skeleton sitting with a (unreadable)."

Replica of gravestone located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaque translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan Culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Original is from Izapa, Chiapas. Represents a skeleton sitting with a (unreadable)." Replica of gravestone located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaque translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan Culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Bas relief from Izapa, Chiapas depicting the decapitation of someone."

Replica of gravestone located in Metro Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The accompanying plaque translates to "Gravestone of Izapa – Mayan Culture – Preclassic Period – Description: Bas relief from Izapa, Chiapas depicting the decapitation of someone." Stele 50 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Stele 50 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Stele 1 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Stele 1 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Stele 21 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. It is also named "the decapitated"

Stele 21 from Izapa on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. It is also named "the decapitated"

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Izapa. |

Notes

- Malmstrom, Vincent "Cycles of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican Civilization" 1997, University of Texas Press (also http://www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/) p. 8

- Clark, John E., "The Beginnings of Mesoamerica: Apologia for the Soconusco Early Formative", research paper authored by the director of the New World Archaeological Foundation, p. 15.

- Pool, p. 264.

- Rice, Prudence M., Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007 ISBN 0292774494 p. 109 (the map of the site is available here as well)

- 2007 Mesoweb Izapa (pdf)

- Rice, Prudence M., Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007 ISBN 0292774494 p. 109

- Malmstrom, Vincent H. "Cycles of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican Civilization", 1997, University of Texas Press (also available online at http://www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/)

- Pool, p. 272.

- Pool (p. 272) and Guernsey (p. 60) both refer to Izapan art's "narrative" quality.

- Guernsey, p. 15.

- Rice, Prudence M., Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007 ISBN 0292774494 p. 110

- Love, M.; Guernsey, J. (2007). "Monument 3 from La Blanca, Guatemala: A Middle Preclassic earthen sculpture and its ritual associations". Antiquity. 81 (314): 920–932. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00096009.

- Culebro, C.A. (1939). Chiapas Pre-Histórico: Su Arqueología. Huixtla, Chiapas: Folleto no. 1.

- Stirling, Matthew W. (1943). Stone Monuments in Southern Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 138, U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Drucker, Philip (1948). "Preliminary Notes on an Archaeological Survey of the Chiapas Coast". Middle American Research Records. 1 (11): 151–169.

- Lowe, Gareth; Lee, Thomas A., Jr.; Martinez Espinoza, Eduardo (1982). 'Izapa: An Introduction to the Ruins and Monuments. Provo: Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 31, Brigham Young University.

- Lowe, Gareth; Lee, Thomas A., Jr.; Martinez Espinoza, Eduardo (1982). 'Izapa: An Introduction to the Ruins and Monuments. Provo: Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation 31. Brigham Young University.

- Ekholm, Susanna M. (1969). 'Mound 30a and the Early Preclassic Sequence of Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico. Provo: Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 73, Brigham Young University.

- Gómez Rueda, Hernando (1995). "Exploración de Sistemas Hidráulicos en Izapa" (PDF). 'VIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala: 6–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Rosenswig, Robert M.; Lopez-Torrijos, Ricardo; Antonelli, Caroline E.; Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2013). "Lidar Mapping and Surface Survey of the Izapa State on the Tropical Piedmont of Chiapas, Mexico". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (3): 1493–1507. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.10.034. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Rosenswig, Robert M.; López-Torrijos, Ricardo; Antonelli, Caroline E. (2015). "Lidar Data and the Izapa Polity: New Results and Methodological Issues from Tropical Mesoamerica". Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences. 7 (4): 487–504. doi:10.1007/s12520-014-0210-7. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Rosenswig, Robert M.; Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2016). "Izapa and the Soconusco Region, Mexico, in the First Millennium A.D." Latin American Antiquity. 27 (3): 357–377. doi:10.7183/1045. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2017). 'Resilience and Interregional Interaction at the Early Mesoamerican City of Izapa: The Formative to Classic Period Transition. Albany, NY: Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, SUNY.

References

- Coe, Michael D. (1962) Mexico, Frederick A. Praeger, New York.

- Culebro, C.A. (1939) Chiapas Pre-Histórico: Su Arqueología. Folleto no. 1. Huixtla, Chiapas.

- Drucker, Philip (1948) Preliminary Notes on an Archaeological Survey of the Chiapas Coast. Middle American Research Records 151–169.

- Ekholm, Susanna M. (1969) Mound 30a and the Early Preclassic Sequence of Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation 73. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Evans, Susan Toby. Ancient Mexico & Central America, Thames and Hudson, London, 2004.

- Gómez Rueda, Hernando (1995) Exploración de Sistemas Hidráulicos en Izapa. In VIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1994 pp. 9–18. Guatemala.

- Guernsey, Julia (2006) Ritual and Power in Stone: The Performance of Rulership in Mesoamerican Izapan Style Art, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, ISBN 978-0-292-71323-9.

- Laughton, Timothy, (1997) Sculpture on the Threshold: The Iconography of Izapa and its Relationship to that of the Maya. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Essex.

- Lowe, Gareth, Thomas A. Lee, Jr., and Eduardo Martinez Espinoza (1982) Izapa: An Introduction to the Ruins and Monuments. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 31. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Malstrom, Vincent H., Izapa: Cultural Hearth of the Olmecs?

- Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2017) Resilience and Interregional Interaction at the Early Mesoamerican City of Izapa: The Formative to Classic Period Transition. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, SUNY.

- Norman, V. Garth, (1973) Izapa Sculpture, Part 1: Album. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation 30. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Pool, Christopher (2007) Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3.

- Rosenswig, Robert R.; Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2016). "Izapa and the Soconusco Region, Mexico, in the First Millennium A.D.". Latin American Antiquity. 27 (3): 357–377. doi:10.7183/1045.

- Rosenswig, Robert M.; López-Torrijos, Ricardo; Antonelli, Caroline E.; Mendelsohn, Rebecca R. (2013). "Lidar Mapping and Surface Survey of the Izapa State on the Tropical Piedmont of Chiapas, Mexico". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (3): 1493–1507. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.10.034.

- Rosenswig, Robert M.; López-Torrijos, Ricardo; Antonelli, Caroline E. (2015). "Lidar Data and the Izapa Polity: New Results and Methodological Issues from Tropical Mesoamerica". Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences. 7 (4): 487–504. doi:10.1007/s12520-014-0210-7.

- Smith, Virginia G., Izapa Relief Carving: Form, Content, Rules for Design, and Role in Mesoamerican Art History and Archaeology, Dumbarton Oaks, 1984.

- Stirling, Matthew W. (1943) Stone Monuments in Southern Mexico. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 138, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.