Isobutane

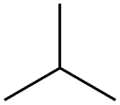

Isobutane, also known as i-butane, 2-methylpropane or methylpropane, is a chemical compound with molecular formula HC(CH3)3. It is an isomer of butane. Isobutane is a colourless, odourless gas. It is the simplest alkane with a tertiary carbon. Isobutane is used as a precursor molecule in the petrochemical industry, for example in the synthesis of isooctane.[6]

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methylpropane[1] | |||

| Other names

Isobutane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 1730720 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.780 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E943b (glazing agents, ...) | ||

| 1301 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1969 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C4H10 | |||

| Molar mass | 58.124 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density |

| ||

| Melting point | −159.42 °C (−254.96 °F; 113.73 K)[2] | ||

| Boiling point | −11.7 °C (10.9 °F; 261.4 K)[2] | ||

| 48.9 mg⋅L−1 (at 25 °C (77 °F))[3] | |||

| Vapor pressure | 3.1 atm (310 kPa) (at 21 °C (294 K; 70 °F))[4] | ||

Henry's law constant (kH) |

8.6 nmol⋅Pa−1⋅kg−1 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Isobutanium | ||

| −51.7·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

96.65 J⋅K−1⋅mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−134.8 – −133.6 kJ⋅mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.86959 – −2.86841 MJ⋅mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | See: data page praxair.com | ||

| GHS pictograms |  | ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

| H220 | |||

| P210 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −83 °C (−117 °F; 190 K) | ||

| 460 °C (860 °F; 733 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.4–8.3% | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

None[5] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 800 ppm (1900 mg/m3)[5] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[5] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkane |

Isopentane | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Uses

Isobutane is the principal feedstock in alkylation units of refineries. Using isobutane, gasoline-grade "blendstocks" are generated with high branching for good combustion characteristics. Typical products from isobutane are 2,4-dimethylpentane and especially 2,2,4-trimethylpentane.[7]

Solvent

In the Chevron Phillips slurry process for making high-density polyethylene, isobutane is used as a diluent. As the slurried polyethylene is removed, isobutane is "flashed" off, and condensed, and recycled back into the loop reactor for this purpose.[8]

Precursor to tert-Butyl hydroperoxide

Isobutane is oxidized to tert-Butyl hydroperoxide, which is subsequently reacted with propylene to yield propylene oxide. The tert-butanol that results as a by-product is typically used to make gasoline additives such as methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE).

Miscellaneous uses

Isobutane is also used as a propellant for aerosol cans.

Isobutane is used as part of blended fuels, especially common in fuel canisters used for camping.[9]

Refrigerant

Isobutane is used as a refrigerant.[10] Their use in refrigerators started in 1993 when Greenpeace presented the Greenfreeze project with the German company Foron.[11] In this regard, blends of pure, dry "isobutane" (R-600a) (that is, isobutane mixtures) have negligible ozone depletion potential and very low global warming potential (having a value of 3.3 times the GWP of carbon dioxide) and can serve as a functional replacement for R-12, R-22 (both of these being commonly known by the trademark Freon), R-134a, and other chlorofluorocarbon or hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants in conventional stationary refrigeration and air conditioning systems.

As a refrigerant, isobutane poses an explosion risk in addition to the hazards associated with non-flammable CFC refrigerants. Substitution of this refrigerant for motor vehicle air conditioning systems not originally designed for isobutane is widely prohibited or discouraged.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Vendors and advocates of hydrocarbon refrigerants argue against such bans on the grounds that there have been very few such incidents relative to the number of vehicle air conditioning systems filled with hydrocarbons.[19][20]

Nomenclature

The traditional name isobutane was still retained in the 1993 IUPAC recommendations,[21] but is no longer recommended according to the 2013 recommendations.[1] Since the longest continuous chain in isobutane contains only three carbon atoms, the preferred IUPAC name is 2-methylpropane but the locant (2-) is typically omitted in general nomenclature as redundant; C2 is the only position on a propane chain where a methyl substituent can be located without altering the main chain and forming the constitutional isomer n-butane.

References

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 652. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

The names ‘isobutane’, ‘isopentane’ and ‘neopentane’ are no longer recommended.

- Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- "Solubility in Water". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Isobutane". CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. CDC. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0350". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Patent Watch, July 31, 2006". Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- Bipin V. Vora; Joseph A. Kocal; Paul T. Barger; Robert J. Schmidt; James A. Johnson (2003). "Alkylation". Kirk‐Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0112112508011313.a01.pub2. ISBN 0471238961.

- Kenneth S. Whiteley. "Polyethylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487.pub2.

- Rietveld, Will (2005-02-08). "Frequently Asked Questions About Lightweight Canister Stoves and Fuels". Backpacking Light. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- "European Commission on retrofit refrigerants for stationary applications" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Page - March 15, 2010 (2010-03-15). "GreenFreeze". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- "U.S. EPA hydrocarbon-refrigerants FAQ". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Compendium of hydrocarbon-refrigerant policy statements, October 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- "MACS bulletin: hydrocarbon refrigerant usage in vehicles" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Society of Automotive Engineers hydrocarbon refrigerant bulletin". Sae.org. 2005-04-27. Archived from the original on 2005-05-05. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Saskatchewan Labour bulletin on hydrocarbon refrigerants in vehicles". Labour.gov.sk.ca. 2010-06-29. Archived from the original on 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- VASA on refrigerant legality & advisability Archived January 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Queensland (Australia) government warning on hydrocarbon refrigerants" (PDF). Energy.qld.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 16 October 1997". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. 1997-10-16. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 29 June 2000". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 May 2005. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Panico, R. & Powell, W. H., eds. (1994). A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Compounds 1993. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03488-2. http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/93/r93_679.htm