Is God Dead?

"Is God Dead?" was an April 8, 1966, cover story for the news magazine Time.[1] A previous article, from October 1965, had investigated a trend among 1960s theologians to write God out of the field of theology. The 1966 article looked in greater depth at the problems facing modern theologians, in making God relevant to an increasingly secular society. Modern science seemed to have had eliminated the need for religion to explain the natural world, and God took up less and less space in people's daily lives. The ideas of various scholars were brought in, including the application of contemporary philosophy to the field of theology, and a more personal, individual approach to religion.

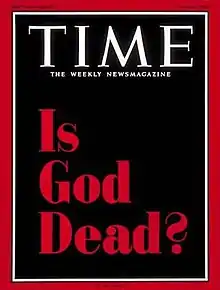

The issue drew heavy criticism, both from the broader public and from clergymen. Much of the criticism was directed at the provocative magazine cover, rather than the content of the article. The cover—all black with the words "Is God Dead?" in large red text—marked the first time in the magazine's history that text with no accompanying image was used. In 2008, the Los Angeles Times named the "Is God Dead?" issue among "12 magazine covers that shook the world".[2]

Background

In 1966, Otto Fuerbringer had been editor of the news magazine Time for six years.[3] He helped to increase the circulation of the magazine, partly by changing its rather austere image. Though a conservative himself, he made the magazine focus extensively on the counter-culture and the political and intellectual radicalism of the 1960s.[4] A best-selling 1964 issue, for instance, had dealt with the sexual revolution.[4] Already in October 1965 the magazine had published an article on the new radical theological movement.[5]

The April 8, 1966, cover of Time magazine was the first cover in the magazine's history to feature only type, and no photo.[6] The cover—with the traditional, red border—was all black, with the words "Is God Dead?" in large, red text. The question was a reference to Friedrich Nietzsche's much-quoted postulate "God is dead" (German: Gott ist tot),[7] which he first proposed in his 1882 book The Gay Science.

Themes presented by the article

The problems

The article accompanying the magazine cover, titled "Toward a Hidden God" and written by religion editor John T. Elson, mentioned the so-called "God Is Dead" movement only briefly in its introduction. In a footnote it identified the leaders of the movement as "Thomas J. J. Altizer of Emory University, William Hamilton of Colgate Rochester Divinity School, and Paul van Buren of Temple University", and explained how these theologians had been trying to construct a theology without God. This theme had already been dealt with in greater detail in the shorter and less prominent article "The "God Is Dead" Movement", on October 22, 1965.[8]

Nietzsche's thesis was that striving, self-centered man had killed God, and that settled that. The current death-of-God group believes that God is indeed absolutely dead, but proposes to carry on and write a theology without theos, without God.

— Toward a Hidden God

The article pointed out that while this movement had roots in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, it also drew on a broader range of thinkers. For example, philosophers and theologians like Søren Kierkegaard and Dietrich Bonhoeffer expressed concerns about the role of God in an increasingly secularised world. The immediate reality did not indicate a death of God or religion; Pope John XXIII's Second Vatican Council had done much to revitalize the Roman Catholic Church, while in the United States, as many as 97% declared a belief in God. Evangelical ministers such as Billy Graham and Christian artists like the playwright William Alfred could be brought as witness to the continued vitality of the Christian church. Nevertheless, this religiosity was mostly skin-deep; only 27% of Americans called themselves deeply religious.

The article then went on to explain the history of monotheism, culminating in the omnipresent Catholic church of the European Middle Ages. This zenith, however, was, according to the article, the beginning of the demise of Christianity: as society became increasingly secularised, the religious sphere of society became marginalised. Scientific discovery, from the Copernican Revolution to Darwin's theory of evolution, eliminated much of the need for religious explanations to life. Newton and Descartes were perhaps personally devout men, but their discoveries "explained much of nature that previously seemed godly mysteries."

Possible solutions

Having laid out the philosophical and historical background, the article then asserted that there was still much curiosity among the general population about God and His relation to the world, and that for the modern theologian who wished to address this curiosity, there seemed to be four options:

stop talking about God for awhile, stick to what the Bible says, formulate a new image and concept of God using contemporary thought categories, or simply point the way to areas of human experience that indicate the presence of something beyond man in life.

According to the article, some contemporary ministers and theologians chose to focus on the life and teachings of Jesus, rather than on God, since Christ was a figure with great appeal among the broader population, but this solution ran dangerously close to ethical humanism. Biblical literalism, on the other hand, might have had an appeal to the fervent believer, but did not speak to most people in a world where the language of the Bible was increasingly unfamiliar.

The article described other attempts that had been made to solve to the problems of religion, including the adaptation of contemporary philosophical terminology to explain God, and cited efforts made to adapt the writings of Martin Heidegger and Alfred North Whitehead to modern theology. At the same time it noted that Ian Ramsey of Oxford had spoken of so-called "discernment situations"; situations in life that led man to question his own existence and purpose, and turn towards a greater power. The article concluded that the current crisis of faith could be healthy for the church, and that it might force clergymen and theologians to abandon previously held certainties: "The church might well need to take a position of reverent agnosticism regarding some doctrines that it had previously proclaimed with excessive conviction."[7]

Reaction

The publication of the article immediately led to a public backlash. Editorial pages of newspapers received numerous letters from angry readers, and clergymen vehemently protested the content of the article.[5] Even though the article itself explored the theological and philosophical issues in depth, "[m]any people...were too quick to judge the magazine by its cover and denounced Time as a haven of godlessness".[9] For Time the issue caused around 3,500 letters to the editor—the largest number of responses to any one story in the history of the magazine.[10] Reader criticism was targeted at Thomas J. J. Altizer in particular.[5] Altizer left Emory in 1968, and by the end of the decade the "death of God" movement had lost much of its momentum.[5] In its issue of December 26, 1969, Time ran a follow-up cover story asking, "Is God Coming Back to Life"?[11]

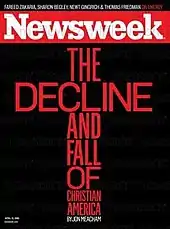

The magazine cover also entered the realm of popular culture: in a scene from the 1968 horror movie Rosemary's Baby, the protagonist Rosemary Woodhouse picks up the issue in a doctor's waiting room.[12] The "Is God Dead?" issue was to have an enduring place in American journalism. In 2008, the Los Angeles Times listed the issue in a featured titled "10 magazine covers that shook the world".[6] In April 2009, Newsweek magazine ran a special report on the decline of religion in the United States under the title "The End of Christian America". This article also referenced the radical "death of God" theological movement of the mid-1960s.[13] The front cover carried the title "The Decline and Fall of Christian America" in red letters on a black background, reminiscent of the 1966 Time cover.[14] The April 3, 2017 cover of Time featured a cover that asked "Is Truth Dead?" in a similar style to the iconic "Is God Dead?" cover, in a cover story about the alleged falsehoods perpetuated by President Donald Trump.[15]

References

- "TIME Magazine Cover: Is God Dead?". Time. 1966-04-08.

- https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-10magazinecovers14-july14-pg-photogallery.html

- Schudel, Matt (2008-08-01). "Otto Fuerbringer; Time Editor in 1960s Helped Start Money, People Magazines". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Hevesi, Dennis (2008-07-30). "Otto Fuerbringer, Former Time Editor, Dies at 97". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Gray, Patrick (2003-04-01). ""God Is Dead" Controversy". Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "10 magazine covers that shook the world". Los Angeles Times. July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "Toward a Hidden God". Time. 1966-04-08. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- This article also mentioned Gabriel Vahanian of Syracuse University, in addition to the three men named above; "The "God Is Dead" Movement". Time. 1965-10-22. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Schudel, Matt (2008-07-31). "Is God Dead? (UPDATED)". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Prendergast, Curtis; Robert T Elson; Geoffrey Colvin; Robert Lubar (1986). Time Inc.: The Intimate History of a Publishing Enterprise (illustrated ed.). Atheneum. p. 112. ISBN 0-689-11315-3.

- "TIME Magazine Cover: Is God Coming Back to Life?". Time. 1969-12-26.

- Rothman, William; Stanley Cavell; Marian Keane (2000). Reading Cavell's The World Viewed. Wayne State University Press. Wayne State University Press. pp. 157. ISBN 978-0-8143-2896-5. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Meacham, Jon (2009-04-04). "The End of Christian America". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Prothero, Stephen (2009-04-27). "Post-Christian? Not even close". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Scherer, Michael. "April 3rd, 2017 - Vol. 189, No. 12 - U.S." Retrieved 22 June 2017.

External links

- Toward a Hidden God— the original article

- A selection of letters to the editor