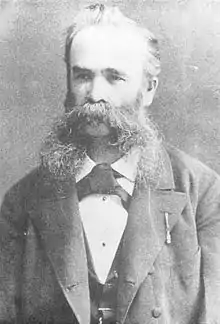

Ioan Pușcariu

Ioan Pușcariu (September 28, 1824 – December 24, 1911) was an Austro-Hungarian ethnic Romanian historian, genealogist and administrator. A native of the Brașov area, he studied law until the 1848 revolution, when he took up arms. After order was restored, he embarked on a four-decade career in government that took him throughout his native Transylvania as well as to Vienna and Budapest. During the 1860s, Pușcariu was involved in the political debates of his province's Romanians, and also helped set up their key cultural organization, Astra. His historical interests lay primarily with the Transylvanian Romanians' nobility and their genealogy; Pușcariu's research into the subject secured his election to the Romanian Academy.

Ioan Pușcariu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 September 1824 |

| Died | 24 December 1911 |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Citizenship | Austria-Hungary |

| Occupation | Historian, genealogist, administrator |

| Movement | Astra |

| Awards | Order of the Iron Crown |

| Honours | Member of the Romanian Academy |

Origins and 1848 revolution

The first-born son of a Romanian Orthodox priest in Sohodol, a village located in the Transylvania region's Brașov County,[1] he had eight siblings, and attended primary school in his native village.[2] In 1834, he entered the German normal school in Brașov, and in 1837, the local Catholic high school. In 1841–1842, he attended the final year of gymnasium at Sibiu, as well as a yearlong theology course.[1] From 1843 to 1845, he took philosophy at the high school in Cluj, remaining for an additional year after completing this cycle. There, his classmates included Nicolae Popea, Avram Iancu and Alexandru Papiu-Ilarian.[3] From 1846 to 1848, he audited courses at the Saxon law faculty in Sibiu. Pușcariu was there when the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 began in Transylvania;[4] he joined the movement in March.[2]

Known as the flag-bearer of the May 1848 Blaj Assembly,[5] he was elected to a 25-member permanent committee of Romanians. Enrolling in the national guard,[2] he was named "major tribune" of his native Burzenland's prefecture starting that October,[5] and around the same time was named a teacher at the Romanian school in Brașov. In November, he was named assessor (councilor) of the Făgăraș district, as well as inspector of the Mândra area.[2] The last important political event of 1848 in which Pușcariu took part was the December assembly at Sibiu, convoked by Metropolitan Andrei Șaguna in order to discuss the problems faced by the Romanian nation in a Transylvania considered "pacified" by General Anton von Puchner. In early 1849, while armed confrontations against Székely forces took place nearby, Pușcariu was able to exercise his administrative functions until Făgăraș was occupied by Józef Bem's troops in March. At that point, he fled across the Rucăr-Bran Pass into Wallachia, remaining until the revolution was crushed.[6]

Administrative and legislative career

Pușcariu then returned home, reoccupying the post of deputy Făgăraș prefect in autumn 1849.[6][7] He was subsequently named commissioner and then circuit judge for the Făgăraș district, holding office from 1850 to 1861.[4] During these years, his seat of jurisdiction shifted from Perșani in 1850 to Viștea de Jos, Deva and Pui, all in 1851, to Veneția de Jos in 1854.[7] From 1861 to 1862, he worked at the imperial Transylvanian chancery in Vienna.[4] He took part in the national assembly of Romanians held at Sibiu in January 1861, serving as secretary; the meeting asked for enhanced rights for the community.[7] From 1862 to 1865, he administered Küküllő County from Cetatea de Baltă, while from 1865 to 1867, he was supreme captain of the Făgăraș district.[4] However, he was unable to pay close attention to the problems of the local Romanians while in this role, as he was a deputy in the Diet of Transylvania during the same period. First sent to this chamber at Sibiu for the 1863–1864 session, he was named by the government to the Cluj Diet of November 1865.[7]

In 1867, following the creation of Austria-Hungary, he became an adviser on matters pertaining to the Orthodox Church at Hungary's Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education in Budapest.[4][7] He took part in the "coronation diet" held at Budapest in 1867–1868. Elected for a Făgăraș seat, he voted against the nationalities law and asked that before Transylvania was absorbed into Hungary proper, discussions be held with the non-Hungarian nationalities.[8] From 1869 to 1890, when he retired, he was a judge on the Curia Regia. He then moved to Bran, near his native village. After his death, Pușcariu was buried in the local family crypt.[4] He and his wife Stana Circa, born in 1831, had four sons: Ion, an engineer and manager in Căile Ferate Române, the state railway carrier of the Romanian Old Kingdom; Iuliu, who became a judge at the court of appeals in Budapest; Emil, a physician and professor at Romania's University of Iași; and Iuliu, a diplomat who represented Austria-Hungary as consul at Tangier and Moscow.[9][10]

Cultural and political involvement

In 1864, thanks to his bureaucratic, administrative and judicial service, Pușcariu was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown, third class, allowing him and his descendants to use the title of knight. He describes the coat of arms he then received in his work on the Romanian noble families of Transylvania. His legal and theological background allowed Pușcariu to help Șaguna draft an organic statute for the church,[4] and he helped convince the government to approve the statute in the spring of 1869.[11] The same year, he took part in a conference at Miercurea Sibiului, where the National Party of Romanians in Transylvania was created. During the event, the proponents of political passivism and activism clashed; Pușcariu figured prominently in the latter camp, arguing that while the Romanian deputies to the diet had achieved little, they had made their voices heard, and that whatever the Romanians did, the Hungarian and Saxon nations would continue to elect deputies and pass laws. Despite these arguments, passivism, a withdrawal from the political life of the new dualist state, was adopted as an official strategy by a wide margin, and its adherents attacked Pușcariu in their newspapers.[12]

Although his position as a judge barred him from overt political activity, he and Șaguna, through the intermediary of his brother Ilarion, continued to discuss relaunching activism. In 1872, he published a brochure containing a political program, but this was rejected both by the Sibiu party meeting in May and by the conference at Alba Iulia the following month. At that point, he essentially withdrew from politics until making a brief return in 1884, when a Romanian Moderate Party was initiated by Miron Romanul. However, few joined the organization, which was met with disapproval by most of the Romanian populace and by the Hungarian government. He was gladdened by the decision to switch to activism was taken in early 1905 by the Romanian National Party.[13]

He played an important role in the founding of Astra, helping to draft the organization's statute, which was approved by Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1861.[4][14] He then served as an active member, addressing its assemblies and working within the historical section.[14] During the association's first general meeting, he delivered a speech underlining the historic value of documents regarding the Romanian noble families of Transylvania, Banat, Crișana, Maramureș and Bukovina. In order to gauge the approximate extent of these families, he launched an appeal to the leaders of his church and of the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church, as well as to prominent figures in the community, asking them to submit data on a prepared form.[4] After retiring to Bran, he supervised the activity of the local Astra chapter. Pușcariu was also involved in the Romanian cultural and church life of Budapest, developing close friendships with community leaders and promoting the construction of a theater. He weighed in on the era's philological disputes, siding with Timotei Cipariu and George Bariț in his preference for an etymological-based orthography.[14]

Contributions to history and genealogy

Elected an honorary member of the Romanian Academy in 1877, Pușcariu rose to titular status in 1900, participating in the organization's general meetings until the end of his life. During his administrative career, Pușcariu was preoccupied by the politics and law of Transylvania, publishing a dictionary of official, bureaucratic terms in Romanian in 1860, with a new edition in 1863. Additionally, a brochure comprising forms for public acts and documents appeared at Vienna in 1861. A particular contributor to his election as a full member of the Academy was the genealogical work Date istorice privitoare la familiile nobile române; covering two volumes and running to 630 pages, it was published at Sibiu in 1892 and 1895, and includes an especially rich genealogical material.[15] The genesis of the project was his Astra appeal of 1862, but it lay largely dormant for three decades, and was only taken up again in earnest after 1890, by which time new scholarly material had been written on the topic, and old documents re-edited.[16] His maiden speech to the Academy, "Ugrinus—1291", focused on history, aiming to rebut Robert Rösler's theory that the ancestors of the Romanians migrated northwards from the south-Danubian area. Pușcariu's view on the origin of the Romanians is that they continually crossed the Danube and the Carpathians, both north and south, from the time of Trajan onwards.[17] His subsequent volumes, chiefly Boierii din Țara Făgărașului, solidified his presence at the forefront of genealogy in the Romanian-speaking lands.[15]

Pușcariu wrote about his own political, scientific and cultural activity, and the material was edited posthumously as Însemnări biografice by Ilarion Pușcariu.[15] His interests extended to his own family history, which he covered in two of his books. Based on preserved tradition, he insisted that a distant ancestor, Iuga, left Maramureș for Moldavia during the reign of Dragoș, after which the family extended into Bessarabia. He asserted that family members crossed into Transylvania in the early 17th century in order to participate in an anti-Ottoman rebellion, and were active in a similar conflict in the first half of the 18th century, during the time of the Cantemirești. He believed they first settled around Cașin and then reached the Brașov area. He was certain that his great-grandfather Bucur, his grandfather Leonte and his father Ioan were all parish priests in Sohodol. He noted that the family used to be called Pușcașiu, connoting a Military Frontier guard (pușcaș meaning "rifleman"). He was the first to be called Pușcariu: in November 1848, revolutionary leaders August Treboniu Laurian and Ioan Bran de Lemény, after he took up the office of assessor, wrote him down as Pușcariu. The rest of the family followed suit in changing its name.[1]

Notes

- Edroiu, p. 2

- Berényi, p. 158

- Edroiu, pp. 2–3

- Edroiu, p. 3

- Josan, p. 287

- Josan, p. 318

- Berényi, p. 159

- Berényi, pp. 159–60

- Ioan Opriș, Alexandru Lapedatu în cultura româneascǎ, p. 14. Bucharest: Editura Științificǎ, 1996. ISBN 978-973-440-190-1

- Octav George Lecca, Familiile boerești române, p. 588. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1899.

- Berényi, p. 160

- Berényi, p. 160-61

- Berényi, p. 161

- Berényi, p. 162

- Edroiu, p. 1

- Edroiu, p. 4

- Chisacof, p. 117

References

- (in Romanian) Maria Berényi, "Ioan Cavaler de Pușcariu (1824–1911)", in Personalități marcante în istoria și cultura românilor din Ungaria (Secolul XIX), pp. 158–163. Gyula: Institutul de Cercetări al Românilor din Ungaria, 2013. ISBN 978-615-5369-02-5

- (in Romanian) Lia Brad Chisacof, "Câte generații de filologi au existat în familia Pușcariu", in Caietele Sextil Pușcariu, II/2015, Cluj-Napoca, pp. 117–125

- Nicolae Edroiu, "Ioan Pușcariu (1824–1911)", in Buletinul Institutului Român de Genealogie și Heraldică "Sever Zotta", nr. 3-4/1997, pp. 1–10

- Nicolae Josan, "Din viața și activitatea lui Ioan Pușcariu (1824–1911) în preajma și în timpul revoluției de la 1848", in Apulum, XIV/1976, pp. 287–320