Insult

An insult is an expression or statement (or sometimes behavior) which is disrespectful or scornful. Insults may be intentional or accidental.[1] An insult may be factual, but at the same time pejorative, such as the word "inbred".[2]

Jocular exchange

Lacan considered insults a primary form of social interaction, central to the imaginary order – "a situation that is symbolized in the 'Yah-boo, so are you' of the transitivist quarrel, the original form of aggressive communication".[3]

Erving Goffman points out that every "crack or remark set up the possibility of a counter-riposte, topper, or squelch, that is, a comeback".[4] He cites the example of possible interchanges at a dance in a school gym:

- A one-liner: Boy: "Care to dance?" Girl: "No, I came here to play basketball" Boy: "Crumbles"

- A comeback: Boy: "Care to dance?" Girl: "No, I came here to play basketball" Boy: "Sorry, I should have guessed by the way you're dressed".[5]

Backhanded compliments

Backhanding is referred to as slapping someone using the back of the hand instead of the palm—that is generally a symbolic, less forceful blow. Correspondingly, a backhanded (or left-handed) compliment, or asteism, is an insult that is disguised as, or accompanied by, a compliment, especially in situations where the belittling or condescension is intentional.[6]

Examples of backhanded compliments include, but not limited to:

- "I did not expect you to ace that exam. Good for you.", which could impugn the target's success as a fluke.[7]

- "That skirt makes you look far thinner.", insinuating hidden fat, with the implication that fat is something to be ashamed of.[7]

- "I wish I could be as straightforward as you, but I always try to get along with everyone.", insinuating an overbearing attitude.[7]

- "I like you. You have the boldness of a much younger person.", insinuating decline with age.[7]

A bittersweet comment is a kind of misinterpretation, mixing positive lines with negative connotation, which may be hinting that he or she is clumsy, informal or awkward hospitality, has trust issues, is attention-seeking, insensitive or inattentive, and using negative connotation for comical effect, and mixing bold lines with positive word play.

Sexuality

Verbal insults often take a phallic or pudendal form; this includes offensive profanity,[8][9] and may also include insults to one's sexuality. There are also insults pertaining to the extent of one's sexual activity. For example, according to James Bloodworth, "incel" has become a "ubiquitous online insult", sometimes being used against the less romantically successful by men who are trying to imply they themselves enjoy sexual abundance.[10]

Formal

The flyting was a formalized sequence of literary insults: invective or flyting, the literary equivalent of the spell-binding curse, uses similar incantatory devices for opposite reasons, as in Dunbar's Flyting with Kennedy.[11]

"A little-known survival of the ancient 'flytings', or contests-in-insults of the Anglo-Scottish bards, is the type of xenophobic humor once known as 'water wit' in which passengers in small boats crossing the Thames ... would insult each other grossly, in all the untouchable safety of being able to get away fast."[12]

Samuel Johnson once triumphed in such an exchange: "a fellow having attacked him with some coarse raillery, Johnson answered him thus, 'Sir, your wife, under pretence of keeping a bawdy-house, is a receiver of stolen goods.'"[13]

Anatomies

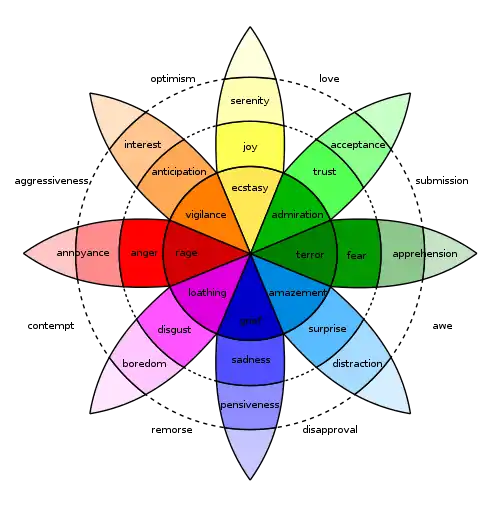

Various typologies of insults have been proposed over the years. Ethologist Desmond Morris, noting that "almost any action can operate as an Insult Signal if it is performed out of its appropriate context – at the wrong time or in the wrong place", classes such signals in ten 'basic categories":[14]

- Uninterest signals

- Boredom signals

- Impatience signals

- Superiority signals

- Deformed-compliment signals

- Mock-discomfort signals

- Rejection signals

- Mockery signals

- Symbolic insults

- Dirt signals

Elizabethans took great interest in such analyses, distinguishing out, for example, the "fleering frump ... when we give a mock with a scornful countenance as in some smiling sort looking aside or by drawing the lip awry, or shrinking up the nose".[15] Shakespeare humorously set up an insult-hierarchy of seven-fold "degrees. The first, the Retort Courteous; the second, the Quip Modest; the third, the Reply Churlish; the fourth, the Reproof Valiant; the fifth, the Countercheck Quarrelsome; the sixth, the Lie with Circumstance; the seventh, the Lie Direct".[16]

Perceptions

What qualifies as an insult is also determined both by the individual social situation and by changing social mores. Thus on one hand the insulting "obscene invitations of a man to a strange girl can be the spicy endearments of a husband to his wife".[17]

See also

- Ad hominem

- Cyber defamation law

- Damning with faint praise

- Defamation

- List of ethnic slurs

- Flag desecration

- Jibe

- Lèse-majesté

- Maledicta

- Maledictology

- Maternal insult

- Mooning

- Name calling

- List of religious slurs

- Rudeness

- List of shoe-throwing incidents

- Taunting

- The Dozens, a game of "one-upmanship" involving insults or snaps usually related to the mother of one's opponent

References

- Erving Goffman, Relations in Public (Penguin 1972) p. 214

- De Vos, George (1990). Status inequality: the self in culture. p. 177.

- Jacques Lacan, Écrits: A Selection (1997) p. 138

- Goffman, pp. 215–216

- Mad, quoted in Goffman, p. 216

- "Backhanded — Definition of Backhanded at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- Burbach, Cherie. "Backhanded Compliment. About Relationships. n.d." about.com. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Desmond Morris, The Naked Ape Trilogy (London 1994) p. 241

- Emma Renold, Girls, Boys, and Junior Sexualities (2005) p. 130

- James Bloodworth (February 2019). "Why incels are the losers in the age of Tinder". unHerd. Retrieved 7 June 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton 1973 )p. 270

- G. Legman, Rationale of the Dirty Joke Vol I (1973) p. 177

- James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson (Penguin 1984) p. 269

- Desmond Morris, Manwatching (London 1987) p. 186-192. ISBN 9780810913103

- George Puttenham in Boris Ford ed., The Age of Shakespeare (1973) p. 72=3

- William Shakespeare. As You Like It, Act V, Scene IV

- Erving Goffman, Relations in Public (1972) p. 412

Further reading

- Thomas Conley: Toward a rhetoric of insult. University of Chicago Press, 2010, ISBN 0-226-11478-3.

- Croom, Adam M. (2011). "Slurs". Language Sciences. 33 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2010.11.005.

External links

| Look up insult in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Insults |

Media related to Insults at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Insults at Wikimedia Commons