Inochentism

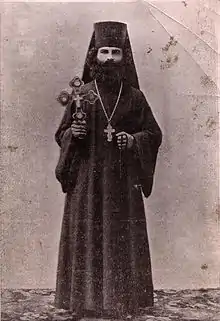

Inochentism (occasionally translated as Innocentism or the Inochentist church; Russian: Иннокентьевцы, Innokentevtsy) is a millennialist and Charismatic Christian sect, split from mainstream Eastern Orthodoxy in the early 20th century. The church was first set up in the Russian Empire, and was later active in both the Soviet Union and Romania. Its founder was Romanian monk Ioan Levizor, known under his monastic name, Inochenție.

The Inochentists, regarded as heretics by Orthodox denominations, traditionally organized themselves into an underground church, and were once thriving in parts of Bessarabia region. Inochenție and his followers were singled out for their alleged preaching of free love and other controversial tenets, but the movement managed to survive Russian persecution and earned a dedicated following, especially among Romanians. It went into decline following its leader's death, and, during World War II, suffered mass deportation to Transnistria. Weakened by Soviet rule, with its anti-religious campaigns and Gulag deportations, it survives in small communities from the general area of Bessarabia—in Romania, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova.

History

Beginnings

The roots of Inochentism relate to Russian rule in Bessarabia (the Bessarabia Governorate), when the Russian Orthodox Church was prevalent and official. According to Inochentist tradition, Cosăuți-born 19-year-old Ioan Levizor was sent by his father to carry some papers to the starosta of the nearby village of Iorjnița (now both villages are in Moldova). When he passed the chapel marking the place of an ancient monastery, he is alleged to have heard voices saying "Ioan! The time has come! Hurry up!" three times and three days later, while passing by the same place, he saw the Mother of God, an appearance which convinced him to become a Russian Orthodox monk at the nearby Monastery of Dobrușa.[1]

Levizor spent three years at the monastery, where he acted as a holy fool, pretending to be a madman in order to push the others toward spiritual awakening. According to his hagiography, the other monks disliked him and Levizor suffered from this, finding his comfort in the Holy Mother's supernatural visits. Despite of his unpopularity among the monks, his superior Archimandrite Porfiri entrusted him with the keys of the monastery, a position from which he used to help those in need, including giving monastery property to the nuns of a nearby convent.[2] In 1897, Levizor left the monastery and wandered across the Russian Empire, moving from monastery to monastery, eventually returning to the Bessarabian Noul Neamț Monastery, founded by Romanian Orthodox monks from Neamț.[3] In 1899, the new Bishop of Kishinev, Yakov, became more open to the use of Romanian language in religious contexts. This allowed the creation of a Moldavian monastery in Balta (now in Ukraine) dedicated to Feodosie Levitzky, a priest known for his philanthropic activities. It was here that Levizor took the monastic name Inochenție.[4]

With the Holy Synod's approval, in 1909, Inochenție moved Feodosie's remains from the cemetery into the church of the monastery. According to hagiographic accounts, a miracle occurred: the "pharisees" who tormented Feodosie during his life found themselves unable to reach the founder's tomb, and it was only Inochenție who was able to get there, for which reason the bishop had to ordain him a priest (a simple deacon, story goes, would have not had the proper authority to accomplish that task). Inochenție used his oratory skills to promote the cult of Feodosie.[4]

Inochenție's leadership

Inochenție, a "Heavenly Emperor", began constructing a "New Jerusalem" in Balta[5] and, by 1911, became known as a miracle worker.[6][7] The ensuing phenomenon was a mass religious movement of peasants from various parts of Bessarabia, but also from Podolia and Kherson; scholar Charles Upson Clark describes Inochenție's Balta as a "Moldavian Lourdes".[6] The new converts considered Inochenție the personification of the Holy Spirit.[8]

The hieromonk was at first encouraged by his monastic superiors, but the Imperial Russian government was alarmed by the political implications and the spread of unorthodox practice, including glossolalia. Officials brought in psychiatrists to investigate the "Balta psychosis"; their reports had it that Inochentism was either an issue of poor nutrition and lack of education (V. S. Yakovenko) or just charlatanism from its leaders (A. D. Kotsovsky).[9] When the large crowds of Bessarabian Romanians (Moldavians) who gathered around Inochenție's cloister were identified as a threat, in February/March 1912 he was transferred to a monastery north of Saint Petersburg, in Murmansk, Olonets Governorate.[10]

The community of Balta continued to thrive even in the absence of their leader and in December 1912, in response to a letter of Inochenție,[11] hundreds of Bessarabian peasants sold their belonging to move in with him in Murmansk.[6] On February 5, 1913, the local abbot, Archimandrite Merkuri, called on the authorities to remove Inochenție and his disciples from the monastery. Within a few days, the Russian Army arrested Inochenție, who was sent to prison in Petrozavodsk, while his followers were sent home in a military convoy.[11]

On August 23, 1913, the Holy Synod condemned Inochenție, whom they found responsible for "spreading demonic and nervous illnesses and even deaths among the people". He remained in prison until he repented; on November 26, 1914, he was released under the supervision of the local bishop.[11] He continued to preach, but in May 1915, he was exiled to Solovetsky Monastery, on the White Sea, living in a skete on the remote Anzersky Island.[6][11] Reportedly, the group preserved a mythical version of these events, which presumes that the church founder died a martyr's death: "In 1914, the Russians set fire to New Jerusalem, and Inochenție was subject to the most horrifying tortures and torments. For 40 days, he was chained, crowned with thorns and made to sit naked on broken glass. The saint's hair and nails were torn out with pliers; and for the course of seven days his left rib was poked at with a spear. Upon seeing that the Holy Prophet has braved all these torments, they proceeded to bury him in the earth, leaving only his head above ground, and for 33 more days they kept feeding him poison. On the fortieth day of torture and martyrdom, the sun went dark, and the saint rose to heaven."[5]

Soviet takeover and Bessarabian survival

Inochenție was however freed following the February Revolution of 1917 and returned to Balta, reunifying the movement which had been divided by schismatic infighting during his absence.[11] Together with several hundreds followers, mainly female and Romanian-speaking, he founded a commune in Ananyiv raion. The commune (named Rai or Raiu, "paradise"), was reportedly designed by a Bessarabian German, and divided along three streets. It covered some 45 hectares, including a vineyard, orchard and garden, a deep pond used in baptism, a wooden church which could hold 600, a hostel and an inner citadel with a tower.[12] Also featured was an intricate underground complex of galleries: from it, Inochenție would "ascend to heaven" every evening. These stone "caves" also held private rooms or prayer cells, and were supposedly the most attractive part of the religious complex.[13] Inochenție died only months later, toward the end of 1917.[11]

Sources attest that, around 1918, the commune was in the care of Simeon Levizor (Inochenție's brother), assisted in this task by fellow "Apostles" Iacob of Dubăsari and Ivan of Cosăuți.[14] On September 14, 1920, the monastery was forcefully closed by the Bolsheviks, while Inochenție's family and the leaders of the Inochentists being either killed or arrested and tried in Odessa.[15] The Rai establishment continued to function in the 1920s, when Ananyiv was included in the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The new Soviet administration tried to transform it into a kolkhoz[7] named "From Darkness to Light".[8] However, in 1930, the Soviet anti-religious newspaper Bezbozhnik announced that Inochentism had been stamped out of Soviet Moldavia, noting that the sect was still active in Romanian Bessarabia.[8] According to one Romanian account of the mid 1920s, the Inochentists were even making converts in the west and south, among peasants from the "Old Kingdom".[16] By the 1940s, the estimated total of Romanian Inochentists was 2,000.[17] The surviving Inochentist sections in Soviet lands suffered during the Great Purge: all the Inochentist nuns still living at Rai were put to death by the NKVD.[18]

In Romanian territories, the movement became the subject of renewed media and political interest, while coming into conflict with the prevalent Romanian Orthodox Church. The new keepers of Inochentist doctrines, described as by "charlatans" by Clark,[6] were self-appointed patriarchs, deemed incarnations of the Holy Spirit or Second Comings of Christ.[19] The government perceived the movement as "harmful" for Romanian society and in contradiction with public order, so, in 1925, the Inochentist church was officially banned.[20] In 1926, a church leader was arrested by Romanian authorities as he tried to set up a new congregation in Budești.[6]

Romanian state repression

During mid 1930, the surviving branches were investigated by the authorities, who took with them field reporters from Dimineața daily. The resulting reports were compiled and analyzed by Romanian scholar and racialist Henric Sanielevici, who focused on their allegations about the Inochentists' sexual promiscuity.[21] At the time, the congregations had resorted to holding mass in Bessarabia's caves, forests and catacombs; from 1928, the church was presided upon by the 35-year-old Neculai Barbă Roșie ("Red Beard"), formerly a Gendarme in Cetatea Albă County, and two "eunuchs" (Ion Antiminiuc, Ivan Strugarin).[19]

Successive Romanian governments continued to issue anti-sectarian directives targeting the church. One such act, passed in 1937 by the Gheorghe Tătărescu cabinet, prohibited the activities of Inochentists, whom it grouped together with the Old Calendar Orthodox, the Pentecostals, the Nazarenes, the Apostolic Faith Church of God, Jehovah's Witnesses and Bible societies.[22] Official Christian propaganda warned Romanians to shun the dissident preachers, who lacked "the godly gift of preaching God's law", be they Inochentists, "Tudorites" or Adventists.[23] Interest in the activities of Inochenție's followers was kept alive by Romanian writer Sabin Velican, in his 1939 novel Pământ nou ("New Land"); it fictionalizes the movement's alleged sexual practices.[24]

Bessarabia's Inochentists fared badly during World War II. In 1941, the region changed hands between a Soviet administration and Nazi-allied Romania. The region's recovery through Romania's participation in Operation Barbarossa was welcomed by Romanian intellectuals. In a special issue of the official literary magazine, Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Orthodox theologian Gala Galaction paid tribute to "the Balta movement" as a Romanian mystical phenomenon, placing in doubt allegations made about the Inochentists' heretical stances.[25]

However, in summer 1942, Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu gave the order that virtually all conscientious objectors belonging to the Inochentist church to be deported to the concentration camps in Transnistria, together with the Bessarabian Jews and nomadic Roma.[26] During the Antonescu years, Romanian Orthodox Church authorities also received help for setting up a special mission to Transnistria, which was designed to target local Inochentist and Baptist communities.[27] Some Baptists and Jehovah's Witnesses, taken together with the Inochentists, were deported from other areas to internment sites in Transnistria.[28] At his 1946 trial, Antonescu acknowledged some of these measures: "Many Romanians, unfortunately, joined these sects in order to escape the war [...]. What was the spiritual basis of these sects? To avoid taking up arms and fighting. So when we called them up, they refused to lay their hands on a weapon. There was a general revolt, and so I brought in a law introducing the death penalty. I did not apply it. And I succeeded in getting rid of these sects. The more recalcitrant ones I seized and deported."[29]

Gulag and later revival

After Bessarabia was again incorporated in the Soviet Union as the Moldavian SSR, the Inochentists gathered their ranks and established a new center in the city of Bălți.[30] They were accused by the Soviet authorities of sabotaging the state plan for agricultural deliveries and resisting the collectivization of agriculture by withholding grain from the authorities. This was, however, a thing common to the Moldavian peasants of all religions.[8] In a memorandum dated October 17, 1946, B. Kozachenko, the Vice-minister of State Security of the Moldavian SSR, reported that virtually every village in four districts of Bessarabia (Bălți, Soroca, Orhei and Chișinău) each had a group of Inochentists, and that their priests were among the "most reactionary and backward".[31] This memorandum resulted in a repression of the Inochentists, which started only a few months later. In January 1947, ten Inochenist leaders were sentenced to terms between six and ten years in the "corrective labor camps".[32]

On April 6, 1949, Operation South began, as a mass deportation to Siberia of people (and their families) who were suspected of anti-Soviet feelings. This included 35,000 people, not just wealthy peasants and former landowners, but also members of sects deemed illegal, including Inochentists. Two years later, on March 3, 1951, another wave of deportations began, as Operation North, which also deported all members of the Jehovah's Witnesses. The deportees were allowed to return home only after Soviet leader Joseph Stalin died and Nikita Khrushchev gave his famous De-Stalinization speech of 1956. According to a 1957 report, 150 Inochentists were back in the Moldavian SSR.[32]

In April and May 1957, another group of Inochentist leaders were arrested. The main local newspaper, Sovetskaya Moldaviya, ran attacks on the Inochenitists and a negative propaganda film was made in reference to them. The persecutions were intensified during Khrushchev's campaign of religious persecutions, which lasted between 1959 and 1964. By the end of the campaign, 20 illegal churches and all the monasteries that supported to the movement from its very beginning had been closed, all of them in the Moldavian SSR.[32] Internal memos of the Soviet administration show that the campaign was relatively successful: in 1960, a report had it that the number of Inochenitists dropped from 2,000 to just 250. Nevertheless, their religious group survived and the Soviet authorities continued publishing pamphlets even in the 1980s. In 1987, it was reported that an Inochentist community still existed near the ruins of Inochenție's monastery in Balta, Ukrainian SSR.[33] Meanwhile, the location where Inochenție began his mission had been turned into a gym.[34]

Inside Romania, itself under a communist government from 1948 to 1989, the Inochentists continued to be explicitly banned alongside Jehovah's Witnesses, Bible students and the other groups listed in 1930s bans. The basic legislation was Government Decree 243, passed in September 1948. It resulted in a circular letter of the Internal Affairs Ministry, which included the listed Inochentists and other Orthodox splinter groups among the lesser threats by comparison with foreign-born new religions, and specified of the former: "These banned religious associations are intensely active in propagating anarchic ideas which damage public opinion and the security of the State. All those who are suspected of being affiliated with these sects are to be held under continuous supervision, tracked down in all their enterprises, and, once certified, they are to be sent to court."[35]

Although Inochentism was not included among those movements who could seek assistance abroad, and who were therefore listed as especially dangerous, Romanian officials even assumed that the Inochentists were spying for the United States.[36] The discrepancies were noted by researcher Nicolae Ioniță, who found that homegrown sects, Inochentism included, were much more exposed to persecution than international churches.[37]

An Inochentist revival was taking place in the two decades after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In the late 1990s, an elderly Inochentist group was still residing in Balta, the "New Jerusalem" envisioned by Inochenție.[34] Another presence was noticed elsewhere in Ukraine's Odessa Oblast. The story was covered in 2010 by Segodnya newspaper, who cited cases of Inochentists who awaited the Second Coming, built at a new subterranean monastery, and vocally demanded that Inochenție be recognized a saint of the Russian Orthodox Church (which still refers to them as to a heretic sect).[30] Most adherents, however, are residents of either Romania or the Republic of Moldova—a few thousands, mostly descendants of 1920s converts.[30]

Beliefs

Identity

Inochentism was described by various outside witnesses as appealing only to ignorant and superstitious masses. Dr. V. S. Yakovenko described its adherents as afflicted by "abuse of liquor and poor food", "spiritual darkness", and a "low level of intellectual and moral development", arguing that this degeneration was favored by anti-Moldavian education policies in the Bessarabia Governorate, before 1917.[6] Yakovenko adds: "In their ignorance [the Inochentists] are very credulous, and take as gospel all they hear, and particularly what comes to them from the church and in their own language."[6] A similar point was made later by Bessarabian historian Nicolae Popovschi, who mentioned some positive aspects of the movement, while also attributing its success to Bessarabian underdevelopment.[38] However, according to Romanian theologian Laurențiu D. Tănase, the ideological source of Inochentism is to be found in the 17th-century Raskol phenomenon, which split Russian Orthodoxy and had a number of ramifications in Romania. Tănase lists Inochentism together with Lipovan Orthodoxy, the Dukhobortsy, the Molokany, the Skoptsy, the Popovtsy and the Bezpopovtsy.[39]

The Inochentists were monarchists: specifically, they supported the Romanov dynasty, even after the Russian Revolution and the union of Bessarabia to Romania, believing that Mikhail Fyodorovich, founder of the dynasty, was really Archangel Michael; the cult of Michael was merged by them with that of the Romanovs.[8] In the 1940s, one preacher, named Ivan Georgitsa (Ion Gheorghiță) was alleged to have spread rumors that Nicholas II of Russia was still alive and that he would soon come to power again. Another incident happened in 1945 or 1946. One sect member, named Romanenko, allegedly posed as the Tsarevich Aleksei and another as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, wearing Imperial garments, as members of the sect fell on their knees in front of them and kissed their hands and feet.[8]

Paradoxically, Inochentism had most impact among Romanian-speaking peasants, as noted by Popovschi: "Even in cases where a village was inhabited by Romanians and foreigners [...], only the Romanians would adhere to Inochentism. In those Bessarabian counties were the population was of a different nationality, Inochentism found no adherents."[16] The replacement of Slavonic sermons with vernacular speeches gave the movement a boost and formed part of its culture.[4][6] Ethnographer Dorin Lozovanu assessed that Inochentism itself was a grassroots form of Romanian cultural emancipation, offering a venue for Romanian speakers throughout southwestern Russian and Soviet lands. Lozovanu interviewed old Inochentists in Balta, who spoke the Moldavian dialect and refused to apply for Ukrainian citizenship.[34]

Controversial beliefs

Millenarianism (or apocalypticism) is among the better known aspects of Inochentist teaching: as noted in 1926 by Nicolae Popovschi, Inochenție preached an impending arrival of the Antichrist. In 1912, while staying in Murom, the hieromonk allegedly stated that the world would end on April 12, 1913, demanding a ban on marriages and speaking in praise of free love.[40] At Balta, Levizor allegedly kept several mistresses, danced with naked virgins, and invented a ritual for spreading chrism over the genitalia of women disciples.[41]

Alongside spontaneous dancing, Inochentist meetings involved direct revelation and glossolalia.[42] In Balta, the pilgrims trembled uncontrollably, shook their limbs, groaned, hiccuped, beat themselves and spoke in tongues. Sometimes, this happened even after they returned home and they even spread out to others. Many considered that these were signs sent by God, so that their innocent suffering would redeem the rest of the sinful world and prepare the world for the Kingdom of God. Those affected by them were called "martyrs" and thought to have supernatural powers, such as clairvoyance and the power to predict the future.[43] The recourse to mortification is said to have originated during one of Inochenție's addresses, when an anonymous believer deliberately injured his own skull—the blackened bruise was hailed by the church founder as a sign that a "New Man" with colored skin was about to emerge in the world.[44]

These habits, alongside suspicions that Inochenție was a confidence artist, escalated the conflict between Inochentists and the Orthodox Church: various Orthodox missionaries and scholars issued strong warnings against Inochenție's dogma.[44] Some grave concerns about Inochentist teachings were raised by the Romanian press in and around 1930. Dimineața spoke at length about the movement's approval of mortification and selective castration, Christian communism, nudism, sacred prostitution, group sex and alcohol abuse.[45] The newspaper also reports that Barbă Roșie's promotion to the rank of Patriarch was based on his claim to have been visited by the ghost of Inochenție, back in 1928.[46] The Inochentists held special prayer meetings during which they venerated the photograph of Inochenție, believing that they would experience miraculous visits of the Holy Spirit.[47]

Sanielevici, who credited these reports, noted a resemblance between the Inochentists and earlier sectarian movements in Russia, as depicted by writer Dmitry Merezhkovsky; following up on his own global theory, Sanielevici concluded that all such phenomena originated with an underground "Semitic" and "Dionysian" culture.[48]

Notes

- Clay, pp. 251–252.

- Clay, p. 252.

- Clay, p. 253.

- Clay, p. 254.

- Sanielevici, p. 105.

- Charles Upson Clark, Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea: Chapter XI, "Russification of the Church", University of Washington Electronic Text Archive.

- Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia and the Politics of Culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 2000, pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-8179-9792-X

- Walter Kolarz, Religion in the Soviet Union, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1961, pp. 365–367.

- Clay, pp. 254–256.

- Clay, p. 258.

- Clay, p. 259.

- Sanielevici, pp. 108–111.

- Sanielevici, pp. 109–110.

- Sanielevici, p. 110.

- Clay, p.259

- Sanielevici, p. 112.

- Deletant, p. 187; Ioanid, p. 293.

- (in Romanian) Nicolae Dabija, "Katyn-uri basarabene", in Literatura și Arta, Nr. 24/2010, p. 1.

- Sanielevici, pp. 101–105.

- Tănase, p. 35.

- Sanielevici, p. 90, 100–115.

- (in Romanian) "Interzicerea sectelor și asociațiilor religioase", in Vestitorul, Nr. 17–18/1937, p. 165 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library).

- Pr. P. M., "Pilda talanților", in Grănicerul. Publicație Lunară pentru Educația Ostașului Grănicer, March 1935, p. 37.

- George Călinescu, Istoria literaturii române de la origini până în prezent, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1986, p. 928, 1027.

- Gala Galaction, "Mănăstiri basarabene", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 8–9/1941, p. 369.

- Deletant, p. 187; Ioanid, pp. 198–199, 293; Michael Mann, The Dark Side of Democracy. Explaining Ethnic Cleansing, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge etc., 2006, pp. 305, 316. ISBN 978-0-521-53854-1

- Paul A. Shapiro, "Faith, Murder, Resurrection. The Iron Guard and the Romanian Orthodox Church", in Kevin P. Spicer, Antisemitism, Christian Ambivalence, and the Holocaust, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2007, p. 159. ISBN 0-253-34873-0

- Ioanid, pp. 198–199, 293.

- Deletant, p. 73.

- (in Romanian) "Misterioșii adepți ai ieromonahului eretic Inochentie", in România Liberă online edition, May 22, 2010; retrieved August 15, 2011.

- Clay, p. 259.

- Clay, p. 260.

- Clay, p. 261.

- (in Romanian) Dorin Lozovanu, "Balta – orașul în care românii nu au spus niciodată bună ziua pe rusește", in Revista Română (ASTRA), Nr. 3/1998.

- (in Romanian) Nicolae Videnie, "1948. Tragedia bisericilor din România. Legislație", at the Memoria Digital Library; retrieved August 15, 2011.

- (in Romanian) William Totok, "Episcopul, Hitler și Securitatea (I)", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 252-253, December 2004.

- (in Romanian) Nicolae Ioniță, " 'Martorii lui Iehova' în arhivele Securității române – problema tolerării activității cultului", in Caietele CNSAS, Nr. 2/2008, p. 201.

- Sanielevici, p. 106, 112.

- Tănase, p. 37.

- Sanielevici, p. 106.

- Sanielevici, pp. 106–108.

- Clay, pp. 254–256; Sanielevici, p. 108.

- Clay, pp. 254–256.

- Sanielevici, p. 107.

- Sanielevici, pp. 101–115.

- Sanielevici, pp. 104–105.

- Clay, p. 251.

- Sanielevici, passim.

References

- J. Eugene Clay, "Apocalypticism in the Russian Borderlands: Inochentie Levizor and His Moldovan Followers", in Religion, State and Society, Volume 26, Issue 3–4, 1998, pp. 251–263.

- Dennis Deletant, Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonescu and His Regime, Romania, 1940–1944, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2006. ISBN 1-4039-9341-6

- Radu Ioanid, La Roumanie et la Shoah, Maison des Sciences de l'homme, Paris, 2002. ISBN 2-7351-0921-6

- Henric Sanielevici, "Supraviețuiri din mysterele dionysiace la ereticii din Basarabia", in Viața Românească, Nr. 11-12/1930, pp. 84–122.

- Laurențiu D. Tănase, Pluralisation religieuse et société en Roumanie, Peter Lang, Bern, 2008. ISBN 978-3-03911-521-1