Incus

The incus or anvil is a bone in the middle ear. The anvil-shaped small bone is one of three ossicles in the middle ear. The incus receives vibrations from the malleus, to which it is connected laterally, and transmits these to the stapes medially. The incus is so-called because of its resemblance to an anvil (Latin: Incus).

| Incus | |

|---|---|

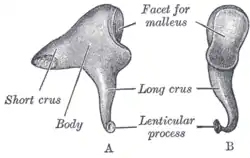

Left incus. A. From within. B. From the front. | |

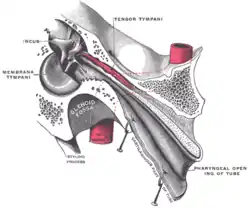

Auditory tube, laid open by a cut in its long axis. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪŋkəs/ |

| Precursor | 1st branchial arch[1] |

| Part of | Middle ear |

| Articulations | Incudomalleolar and incudostapedial joint |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Incus |

| MeSH | D007188 |

| TA98 | A15.3.02.038 |

| TA2 | 888 |

| FMA | 52752 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

|

| This article is one of a series documenting the anatomy of the |

| Human ear |

|---|

Structure

The incus is the second of the ossicles, three bones in the middle ear which act to transmit sound. It is shaped like an anvil, and has a long and short crus extending from the body, which articulates with the malleus.[2]:862 The short crus attaches to the posterior ligament of the incus. The long crus articulates with the stirrup at the lenticular process.

The superior ligament of the incus attaches at the body of the incus to the roof of the tympanic cavity.

Function

Vibrations in the middle ear are received via the tympanic membrane. The malleus, resting on the membrane, conveys vibrations to the incus. This in turn conveys vibrations to the stapes.[2]:862

History

"Incus" means "anvil" in Latin. Several sources attribute the discovery of the incus to the anatomist and philosopher Alessandro Achillini.[3][4] The first brief written description of the incus was by Berengario da Carpi in his Commentaria super anatomia Mundini (1521).[5] Andreas Vesalius, in his De humani corporis fabrica,[6] was the first to compare the second element of the ossicles to an anvil, thereby giving it the name incus.[7] The final part of the long limb was once described as a "fourth ossicle" by Pieter Paaw in 1615.[8]

Additional images

Ossicles

Ossicles Tympanic cavity. Facial canal. Internal carotid artery.

Tympanic cavity. Facial canal. Internal carotid artery. Auditory ossicles. Tympanic cavity. Deep dissection.

Auditory ossicles. Tympanic cavity. Deep dissection. Aditory ossicles. Incus and malleus. Deep dissection.

Aditory ossicles. Incus and malleus. Deep dissection.

References

- hednk-023—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- Alidosi, GNP. I dottori Bolognesi di teologia, filosofia, medicina e d'arti liberali dall'anno 1000 per tutto marzo del 1623, Tebaldini, N., Bologna, 1623. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k51029z/f35.image#

- Lind, L. R. Studies in pre-Vesalian anatomy. Biography, translations, documents, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1975. p.40

- Jacopo Berengario da Carpi,Commentaria super anatomia Mundini, Bologna, 1521. https://archive.org/details/ita-bnc-mag-00001056-001

- Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica. Johannes Oporinus, Basle, 1543.

- O'Malley, C.D. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964. p. 121

- Graboyes, Evan M.; Chole, Richard A.; Hullar, Timothy E. (September 2011). "The Ossicle of Paaw". Otology & Neurotology. 32 (7): 1185–1188. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31822a28df. PMC 3158805. PMID 21844785.

External links

- The Anatomy Wiz Incus