Homosexuality in Japan

Records of men who have sex with men in Japan date back to ancient times. Western scholars have identified these as evidence of homosexuality in Japan. Though these relations had existed in Japan for millennia, they became most apparent to scholars during the Tokugawa (or Edo) period. Historical practices identified by scholars as homosexual include shudō (衆道), wakashudō (若衆道) and nanshoku (男色).[1]

The Japanese term nanshoku (男色, which can also be read as danshoku) is the Japanese reading of the same characters in Chinese, which literally mean "male colors". The character 色 ("color") has the added meaning of "sexual pleasure" in both China and Japan. This term was widely used to refer to some kind of male to male sex in a pre-modern era of Japan. The term shudō (衆道, abbreviated from wakashudō 若衆道, "the way of adolescent boys") is also used, especially in older works.[1]

During the Meiji period nanshoku started to become discouraged due to the rise of sexology within Japan and the process of westernization.

Modern terms for homosexuals include dōseiaisha (同性愛者, literally "same-sex-love person"), okama (お釜, ""kettle"/""cauldron", slang for "gay men"), gei (ゲイ, gay), homo (ホモ) or homosekusharu (ホモセクシャル, "homosexual"), onabe (お鍋, "pot"/"pan", slang for "lesbian"), bian (ビアン)/rezu (レズ) and rezubian (レズビアン, "lesbian").[2]

Pre-Meiji Japan

A variety of obscure literary references to same-sex love exist in ancient sources, but many of these are so subtle as to be unreliable; another consideration is that declarations of affection for friends of the same sex were common.[3] Nevertheless, references do exist, and they become more numerous in the Heian period, roughly in the 11th century. For example, in The Tale of Genji, written in the early 11th century, men are frequently moved by the beauty of youths. In one scene the hero is rejected by a lady and instead sleeps with her young brother: "Genji pulled the boy down beside him ... Genji, for his part, or so one is informed, found the boy more attractive than his chilly sister".[4]

The Tale of Genji is a novel, but there are several Heian-era diaries that contain references to homosexual acts. Some of these contain references to Emperors involved in homosexual relationships with "handsome boys retained for sexual purposes".[5]

Monastic same-sex "love"

Nanshoku relationships inside monasteries were typically pederastic: an age-structured relationship where the younger partner is not considered an adult. The older partner, or nenja (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), would be a monk, priest or abbot, while the younger partner was assumed to be an acolyte (稚児, chigo), who would be a prepubescent or adolescent boy;[6] the relationship would be dissolved once the boy reached adulthood (or left the monastery). Both parties were encouraged to treat the relationship seriously and conduct the affair honorably, and the nenja might be required to write a formal vow of fidelity. Outside of the monasteries, monks were considered to have a particular predilection for male prostitutes, which was the subject of much ribald humor.[7]

There is no evidence so far of religious opposition to homosexuality within Japan in non-Buddhist traditions.[8] Tokugawa commentators felt free to illustrate kami engaging in anal sex with each other. During the Tokugawa period, some of the Shinto gods, especially Hachiman, Myoshin, Shinmei and Tenjin, "came to be seen as guardian deities of nanshoku" (male–male love). Tokugawa-era writer Ihara Saikaku joked that since there are no women for the first three generations in the genealogy of the gods found in the Nihon Shoki, the gods must have enjoyed homosexual relationships—which Saikaku argued was the real origin of nanshoku.[9]

In contrast to the norms in religious circles, in the warrior (samurai) class it was customary for a boy in the wakashū age category to undergo training in the martial arts by apprenticing to a more experienced adult man. According to Furukawa, the relationship was based on the model of a typically older nenja, paired with a typically younger chigo. [1] The man was permitted, if the boy agreed, to take the boy as his lover until he came of age; this relationship, often formalized in a "brotherhood contract",[5] was expected to be exclusive, with both partners swearing to take no other (male) lovers.

This practice, along with clerical pederasty, developed into the codified system of age-structured homosexuality known as shudō, abbreviated from wakashūdō, the "way (Tao) of wakashū".[7] The older partner, in the role of nenja, would teach the chigo martial skills, warrior etiquette, and the samurai code of honor, while his desire to be a good role model for his chigo would lead him to behave more honorably himself; thus a shudō relationship was considered to have a "mutually ennobling effect".[7] In addition, both parties were expected to be loyal unto death, and to assist the other both in feudal duties and in honor-driven obligations such as duels and vendettas. Although sex between the couple was expected to end when the boy came of age, the relationship would, ideally, develop into a lifelong bond of friendship. At the same time, sexual activity with women was not barred (for either party), and once the boy came of age, both were free to seek other wakashū lovers.

Like later Edo same-sex practices, samurai shudō was strictly role-defined; the nenja was seen as the active, desiring, penetrative partner, while the younger, sexually receptive wakashū was considered to submit to the nenja's attentions out of love, loyalty, and affection, rather than sexual desire[1]d] Among the samurai class, adult men were (by definition) not permitted to take the wakashū role; only preadult boys (or, later, lower-class men) were considered legitimate targets of homosexual desire. In some cases, shudō relationships arose between boys of similar ages, but the parties were still divided into nenja and wakashū roles.[1]

Kabuki and male prostitution

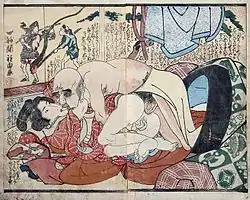

Male prostitutes (kagema), who were often passed off as apprentice kabuki actors and catered to a mixed male and female clientele, did a healthy trade into the mid-19th century despite increasing restrictions. Many such prostitutes, as well as many young kabuki actors, were indentured servants sold as children to the brothel or theater, typically on a ten-year contract. Relations between merchants and boys hired as shop staff or housekeepers were common enough, at least in the popular imagination, to be the subject of erotic stories and popular jokes. Young kabuki actors often worked as prostitutes off-stage, and were celebrated in much the same way as modern media stars are today, being much sought after by wealthy patrons, who would vie with each other to purchase the Kabuki actors favors. Onnagata (female-role) and wakashū-gata (adolescent boy-role) actors in particular were the subject of much appreciation by both male and female patrons, and figured largely in nanshoku shunga prints and other works celebrating nanshoku, which occasionally attained best-seller status.[5][10]

Male prostitutes and actor-prostitutes serving male clientele were originally restricted to the wakashū age category, as adult men were not perceived as desirable or socially acceptable sexual partners for other men. During the 17th century, these men (or their employers) sought to maintain their desirability by deferring or concealing their coming-of-age and thus extending their "non-adult" status into their twenties or even thirties; this eventually led to an alternate, status-defined shudō relationship which allowed clients to hire "boys" who were, in reality, older than themselves. This evolution was hastened by mid-17th-century bans on the depiction of the wakashū's long forelocks, their most salient age marker, in kabuki plays; intended to efface the sexual appeal of the young actors and thus reduce violent competition for their favors, this restriction eventually had the unintended effect of de-linking male sexual desirability from actual age, so long as a suitably "youthful" appearance could be maintained.[11][5]

Art of same-sex love

These activities were the subject of countless literary works, most of which have yet to be translated. However, English translations are available for Ihara Saikaku who created a bisexual main character in The Life of An Amorous Man (1682), Jippensha Ikku who created an initial gay relationship in the post-publication "Preface" to Shank's Mare (1802 et seq), and Ueda Akinari who had a homosexual Buddhist monk in Tales of Moonlight and Rain (1776). Likewise, many of the greatest artists of the period, such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, prided themselves in documenting such loves in their prints, known as ukiyo-e "pictures of the floating world", and where they had an erotic tone, shunga "pictures of spring."[12]

Nanshoku was not considered incompatible with heterosexuality; books of erotic prints dedicated to nanshoku often presented erotic images of both young women (concubines, mekake, or prostitutes, jōrō) as well as attractive adolescent boys (wakashū) and cross-dressing youths (onnagata). Indeed, several works suggest that the most "enviable" situation would be to have both many jōrō and many wakashū.[13] Likewise, women were considered to be particularly attracted to both wakashū and onnagata, and it was assumed that many of these young men would reciprocate that interest.[13] Therefore, both many practitioners of nanshoku and the young men they desired would be considered bisexual in modern terminology. Men and male youths (there are examples of both) who were purely homosexual might be called "woman-haters" (onna-girai); this term, however, carried the connotation of aggressive distaste of women in all social contexts, rather than simply a preference for male sexual partners. Not all exclusively homosexual men were referred to with this terminology.[5]

Exclusive homosexuality and personal sexual identity

The Great Mirror of Male Love (男色大鏡) by Ihara Saikaku was the definitive work on the subject of "male love" in Tokugawa Era Japan. In his introduction to The Great Mirror of Male Love, Paul Gordon Schalow writes, "In the opening chapter of Nanshoku Okagami, Saikaku employed the title in its literal sense when he stated ‘I have attempted to reflect in this great mirror all of the varied manifestations of male love."’[14] It was intended to be a societal reflection of all the different ways men in Tokugawa society loved other men.

The most common narrative of male to male sex and/or love was what we would now consider a "bisexual" experience: the "connoisseur of boys" or shojin-zuki. This term was applied not simply to men who engaged in "bisexual" behavior, but most often to men who engaged sexually and/or romantically with boys often, but not exclusively. However, men who wished to only have sex/form relationships with boys (and men who filled the sociosexual role of "boy"): the exclusively "homosexual" "women haters" or onna-girai, were not stigmatized.[14][5]

In Male Colors by Leupp, he writes "In this brilliant, refined, and tolerant milieu, we have, not surprisingly, evidence of a self conscious sub-culture. Though the Great Mirror occasionally portrays bisexual behavior, it is noteworthy that Saikaku more often depicts devotees of male love as a class who think of themselves as exclusive in their preferences, stress this exclusiveness by calling themselves "women haters" (onna-girai) and forming a unique community—a ‘male love sect’. No other early society shows this phenomenon quite so clearly as seventeenth century Japan."[5]

Paul Gordon Schalow references these concepts in his introduction to the full English translation of The Great Mirror of Male Love, writing, "interestingly, saikaku structured nanshoku okagami not around the "bisexual" ethos of the shojin-zuki, but around the exclusively "homosexual" ethos of the onna-girai."[14]

The poem at the beginning of The Sword That Survived Loves Flame references a heroic "woman hater."

Memories of a rice husker, a woman hater unto death, saving his birthplace from disaster

In this same story, we see a character refer to himself and a friend as "woman-haters" in good humor. "What a couple of woman haters we are!" he exclaims, after they both agree that the love of "beautiful youths" is "the only thing of interest in this world"[15]

There were wakashu who would now be considered "homosexual," wakashu who would now be considered "bisexual," and wakashu who would now be considered "heterosexual," as well as many who could not be easily sorted into these categories.[14][5]

References to wakashu exclusively interested in men were relatively common, as in the example of the popular actor described in the story Winecup Overflowing, who was sent many love letters from women, but who, "ignored them completely, not out of cold heartedness, but because he was devoted to the way of male love."[16]

Wakashu who felt this way could simply transition to being the "man" partner to a "boy," or, in some circumstances (of varying social acceptability), continue his life in the sociosexual role of "boy."[14][5]

There is also much evidence of young men who engaged in this behavior out of duty, rather than love, or lust. Like in, The Boy Who Sacrificed His Life, where Saikaku writes, "it seems that Yata Nisaburo of whom you spoke to me in private is not a believer in boy love. He was not interested in the idea of having a male lover and so, though only seventeen and in the flower of youth, has foolishly cut off his forelocks. I found his profuse apologies rather absurd but have decided to let the matter drop. Last night everyone came over and we spent the whole night laughing about it...."[17]

Another Tokugawa author, Eijima Kiseki, who references exclusive homosexuality, writes of a character in his 1715 The Characters of Worldly Young Men, "who had never cared for women: all his life he remained unmarried, in the grip of intense passions for one handsome boy after another."

There is a genre of stories dedicated to debating the value of "male colors," "female colors," or the "following of both paths." "Colors" here indicating a specific way of sexual desire, with the desire coming from the adult male participant, to the receiving woman or "youth." Depending on what audience the story was written for, the answer to the preferred way of life might be that the best way is to be exclusive to women, moderately invested in both women and boys, or exclusive to boys. Although these "ways of loving" were not considered incompatible, there were people and groups who advocated the exclusive following of one way, considered them spiritually at odds, or simply only personally experienced attractions in line with one of these "ways." [14][5]

Social role play in man and boy roles

Traditional expressions of male to male sexual and romantic activity were between a man who had gone through with his coming of age ceremony, and a male youth who had not.[14][5]

In his introduction to The Great Mirror of Male Love, Schallow writes, "a careful reading of nanshoku okagami makes clear that the constraint requiring that male homosexual relations be between an adult male and a wakashu was sometimes observed only in the form of fictive roleplaying. This meant that relations between pairs of man-boy lovers were accepted as legitimate whether or not a real man and a real boy were involved, so long as one partner took the role of ‘man’ and the other the role of ‘boy."'[14]

In Two Olds Cherry Trees, the protagonists are two men who have been in love since they were youths. The "man" in this relationship is sixty-six, and the "boy" in this relationship is sixty-three.[18]

In the realm of male kabuki (as opposed to "boy" kabuki), Saikaku writes, "now, since everyone wore the hairstyle of adult men, it was still possible at age 34 or 35 for youthful-looking actors to get under a man’s robe...If skill is what the audience is looking for, there should be no problem in having a 70 year old perform as a youth in long sleeved robes. So long as he can continue to find patrons willing to spend the night with him, he can then enter the new year without pawning his belongings."[19]

The protagonist of Saikaku's An Amorous Man hires the services of a "boy" who turns out to be ten years his senior, and finds himself disappointed.[5]

In the Ugetsu Monogatori, written by Ueda Akinari (1734-1809), the story Kikuka no chigiri is commonly believed to be about a romantic relationship between two adult men, where neither obviously holds the sociosexual role of wakashu, though they do structure it with their age difference in mind, using the "male love" terminology "older brother" versus "younger brother." In the story of Haemon and Takashima, two adult men, they also use this terminology, and Takashima additionally presents himself as a wakashu.[5]

Mentions of men who openly enjoy both being the penetrating and penetrated partner are not found in these works, but are found in earlier Heian personal diaries, like in the diary of Fujiwara no Yorinaga, who writes on wanting to perform both the penetrative, and the receptive, sexual role. This is also referenced in a Muromachi era poem by the Shingon priest Socho (1448-1532). This may indicate that the mores surrounding appropriate homosexual conduct for men had changed rapidly in the course of one-to-two centuries.[5]

Meiji Japan

As Japan progressed into the Meiji era, same-sex practices continued, taking on new forms. However, there was a growing animosity towards same-sex practices. Despite the animosity, nanshoku continued, specifically the samurai version of nanshoku, and it became the dominant expression of homosexuality during the Meiji period.[1]

Nanshoku practices became associated with the Satsuma region of Japan. The reason being that this area was deeply steeped in the nanshoku samurai tradition of the Tokugawa period. Also, when the satsuma oligarchs supported the restoration of power to the emperor, they were put into positions of power, allowing nanshoku practices to be brought more into the spotlight during this time period. Satsuma also made up the majority of the newly created Japanese navy, thus associating the navy with nanshoku practices. Though during this time Japan briefly adopted anti-sodomy laws in an attempt to modernize its code, the laws were repealed when a French legalist, G. E. Boissonade, advised adopting a similar legal code to France's. Despite this, nanshoku flourished during the time of the Sino and Russo-Japanese wars. This was due to the association of the warrior code of the samurai with nationalism. This led to close association of the bushido samurai code, nationalism, and homosexuality. After the Russo-Japanese war however, the practice of nanshoku began to die down, and it began to receive pushback.[1]

Rejection of homosexuality

Eventually Japan began to shift away from its tolerance of homosexuality, moving towards a more hostile stance toward nanshoku. The Keikan code revived the notion of making sodomy illegal. This had the effect of criticizing an act of homosexuality without actually criticizing nanshoku itself, which at the time was associated with the samurai code and masculinity. The Keikan code came to be more apparent with the rise of groups of delinquent students that would engage in so called "chigo" battles. These groups would go around assaulting other students and incorporate them into their group, often engaging in homosexual activity. Newspapers became highly critical of these bishōnen-hunting gangs, resulting in an anti-sodomy campaign throughout the country.[1]

Sexology, a growing pseudo-science in Japan at the time, was also highly critical of homosexuality. Originating from western thought, Sexology was then transferred to Japan by way of Meiji scholars, who were seeking to create a more Western Japan. Sexologists claimed that males engaging in a homosexual relationship would adopt feminine characteristics and would assume the psychic persona of a woman. Sexologists claimed that homosexuality would degenerate into androgyny in that the very body would come to resemble that of a woman, with regard to such features such as voice timbre, growth of body hair, hair and skin texture, muscular and skeletal structure, distribution of fatty tissues, body odor and breast development.[11]

Homosexuality in modern Japan

Despite the recent trends that suggest a new level of tolerance, as well as open scenes in more cosmopolitan cities (such as Tokyo and Osaka), Japanese gay men and lesbian women often conceal their sexuality, with many even marrying persons of the opposite sex.[20]

Politics and law

Japan has no laws against homosexual activity and has some legal protections for gay individuals. In addition, there are some legal protections for transgender individuals. Consensual sex between adults of the same sex is legal, but some prefectures set the age of consent for same-sex sexual activity higher than for opposite-sex sexual activity.

While civil rights laws do not extend to protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation, some governments have enacted such laws. The government of Tokyo has passed laws that ban discrimination in employment based on sexual identity.

The major political parties express little public support for LGBT rights. Despite recommendations from the Council for Human Rights Promotion, the National Diet has yet to take action on including sexual orientation in the country's civil rights code.

Some political figures, however, are beginning to speak publicly about they themselves being gay. Kanako Otsuji, an assemblywoman from Osaka, came out as a lesbian in 2005.[21] She became the first elected member of the House of Councillors and of the Diet in 2013 and 2015 respectively to do so. Before that, in 2003, Aya Kamikawa became the first openly transgender person elected official in Tokyo, Japan.[22] Taiga Ishikawa was elected in 2019, becoming the first openly gay man to sit in the Diet. He was out also during his time previously as a ward councillor for Nakano.

The current Constitution of Japan, which was written during American occupation, defines marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman.[23] In an unconventional effort to circumvent marriage restrictions, some gay couples have resorted to using the adult adoption system, which is known as futsu, as an alternate means of becoming a family.[23] In this method, the older partner adopts the younger partner which allows for them to be officially recognized as a family and receive some of the benefits that ordinary families receive such as common surnames and inheritance.[23] In regards to the workplace, there are no anti-discrimination protections for LGBT employees. Employers play a visible role in reinforcing the Confucian tenets of marriage and procreation. Male employees are considered ineligible for promotions unless they marry and procreate.[23]

While same-sex marriage is not legalized at the national level, the Shibuya District in Tokyo passed a same-sex partnership certificate bill in 2015 to "issue certificates to same-sex couples that recognize them as partners equivalent to those married under the law."[24] Similar partnerships are available in Setagaya District (Tokyo), Sapporo (Hokkaido), Takarazuka (Hyogo), and over 20 other localities, as well as one prefecture (Ibaraki).[25][26]

Mass media

A number of artists, nearly all male, have begun to speak publicly about being gay, appearing on various talk shows and other programs, their celebrity often focused on their sexuality; twin pop-culture critics Piko and Osugi are an example.[27] Akihiro Miwa, a drag queen and former lover of author Yukio Mishima, is the television advertisement spokesperson for many Japanese companies ranging from beauty to financial products.[28] Kenichi Mikawa, a former pop idol singer who now blurs the line between male and female costuming and make-up, can also regularly be seen on various programs, as can crossdressing entertainer Peter.[29] Singer-songwriter and actress Ataru Nakamura was one of the first transgender personalities to become highly popular in Japan; in fact, sales of her music rose after she discussed her MTF gender reassignment surgery on the variety show All Night Nippon in 2006.[30]

Some entertainers have used stereotypical references to homosexuality to increase their profile. Masaki Sumitani a.k.a. Hard Gay (HG), a comedian, shot to fame after he began to appear in public wearing a leather harness, hot pants, and cap.[31] His outfit, name, and trademark pelvis thrusting and squeals earned him the adoration of fans and the scorn of many in the Japanese gay community.

Ai Haruna and Ayana Tsubaki, two high-profile transgender celebrities, have gained popularity and have been making the rounds on some very popular Japanese variety shows.[32] As of April 2011, Hiromi, a fashion model, came out publicly as a lesbian.[33]

A greater number of gay and transgender characters have also begun appearing (with positive portrayals) on Japanese television, such as the highly successful Hanazakari no Kimitachi e and Last Friends television series.[34][35] Boys' Love drama Ossan's Love aired first in 2016 as a standalone TV movie and was expanded to a TV series in 2018. The programme was so successful that a movie sequel was released the following year entitled Ossan's Love: LOVE or DEAD. In 2019 male same-sex relationships became further visible with the popular adapated drama What Did You Eat Yesterday?.

Media

The gay magazine Adonis (ja) of the membership system was published in 1952.[36]

In 1975 twelve women became the first group of women in Japan to publicly identify as lesbians, publishing one issue of a magazine called Subarashi Onna (Wonderful Women).[37]

With the rise in visibility of the gay community and the attendant rise of media for gay audiences, the Hadaka Matsuri ("Naked Festival") has become a fantasy scenario for gay videos.[38]

Gei-comi ("gay-comics") are gay-romance themed comics aimed at gay men. While yaoi comics often assign one partner as a "uke", or feminized receiver, gei-comi generally depict both partners as masculine and in an equal relationship.[39] Another common term for this genre is bara, stemming from the name of the first publication of this genre to gain popularity in Japan, Barazoku. Yaoi works are massive in number with much of the media created by women usually for female audiences. In the west, it has quickly caught on as one of the most sought-after forms of pornography. There is certainly no disparity between yaoi as a pornographic theme, vs Yuri.

Lesbian-romance themed anime and manga is known as yuri (which means "lily"). It is used to describe female-female relationships in material and is typically marketed towards straight people, homosexuals in general, or lesbians despite significant stylistic and thematic differences between works aimed at the different audiences. Another word that has become popular in Japan as an equivalent term to Yuri is "GL" (short for "Girls' Love" in opposite to "Boys' Love"). There are a variety of yuri titles (or titles that integrate yuri content) aimed at women, such as Revolutionary Girl Utena, Oniisama e..., Maria-sama ga Miteru, Sailor Moon (most notably the third and fifth seasons), Strawberry Shake Sweet, Love My Life, etc.; and there are a variety of yuri titles of anime such as Kannazuki no Miko, Strawberry Panic!, Simoun, and My-Hime. Comic Yuri Hime is a long-time running manga magazine in Japan that focuses solely on yuri stories, which gained merges from its other subsidiary comics and currently runs as the only Yuri Hime named magazine. Other magazines and anthologies of Yuri that have emerged throughout the early 21st century are Mebae, Hirari, and Tsubomi (the latter two ceased publication before 2014).

See also

- Homosexuality in China

- Human male sexuality

- Japan

- Bara (genre)

- Gay pornography in Japan (in Japanese)

- Gay magazine in Japan (in Japanese)

- Gay video in Japan (in Japanese)

- LGBT rights in Japan

- Sexual minorities in Japan

- Yaoi

- LGBT culture in Singapore

- LGBT history

References

- Furukawa, Makoto. The Changing Nature of Sexuality: The Three Codes Framing Homosexuality in Modern Japan. pp. 99, 100, 108, 112.

- "Intersections: Male Homosexuality and Popular Culture in Modern Japan". intersections.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Flanagan, Damian (2016-11-19). "The shifting sexual norms in Japan's literary history". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- The Tale of Genji. Edward G. Seidensticker (trans.) p. 48.

- Leupp, Gary (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91919-8. pg. 26, 32, 53, 69-78, 88, 90- 92, 94, 95-97, 98-100, 101-102, 104, 113, 119-120, 122, 128-129, 132-135, 137-141, 145..

- Childs, Margaret (1980). "Chigo Monogatari: Love Stories or Buddhist Sermons?". Monumenta Nipponica. Sophia University. 35: 127–51. doi:10.2307/2384336.

- Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. p. 26, 39–42, 75, 70-71, 252,

- The Greenwood encyclopedia of LGBT issues worldwide, Volume 1, Chuck Stewart, p.430; accessed through Google Books

- Leupp 1997, p. 32.

- "Gay love in Japan – World History of Male Love". Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Pflugfelder, M. Gregory. 1999. "Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600- 1950": 256.

- "Japanese Hall". Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Mostow, Joshua S. (2003), "The gender of wakashu and the grammar of desire", in Joshua S. Mostow; Norman Bryson; Maribeth Graybill, Gender and power in the Japanese visual field, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 49–70

- Schallow, Paul (1990). Introduction to The Great Mirror of Male Love. Stanford University Press. pp. 1, 4, 11–12, 29. ISBN 0804718954.

- The Love That Survived Loves Flame, The Great Mirror of Male Love. Paul Gordon Schalow (trans.) p. 138, 139.

- Winecup Overflowing, The Great Mirror of Male Love. Paul Gordon Schalow (trans.) p. 222.

- The Boy Who Sacrificed His Life, The Great Mirror of Male Love. Paul Gordon Schalow (trans.) p. 168.

- Two Old Cherry Trees Still in Bloom, The Great Mirror of Male Love. Paul Gordon Schalow (trans.) p. 181.

- 'Kichiya Riding a Horse, The Great Mirror of Male Love. Paul Gordon Schalow (trans.) p. 215.

- Elizabeth Floyd Ogata (2001-03-24). "'Selectively Out:' Being a Gay Foreign National in Japan". The Daily Yomiuri (on Internet Archive). Archived from the original on 2006-06-17. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- The Japan Times http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20050911x2.html. Retrieved 8 April 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Setagaya OKs transsexual's election bid". 21 April 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2018 – via Japan Times Online.

- Tamagawa, Masami (2016-03-14). "Same-Sex Marriage in Japan". Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 12 (2): 160–187. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2015.1016252. ISSN 1550-428X. S2CID 146655189.

- Hongo, Jun (2015-03-31). "Tokyo's Shibuya Ward Passes Same-Sex Partner Bill". WSJ. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- Dooley, Ben (2019-11-27). "Japan's Support for Gay Marriage Is Soaring. But Can It Become Law?". NYT. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- Maffei, Nikolas (2019-07-01). "Ibaraki Becomes First Prefecture in Japan to Recognize Same-Sex Couples". Shingetsu News Agency. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Findlay, Jamie (7 August 2007). "Pride vs. prejudice". Retrieved 8 April 2018 – via Japan Times Online.

- "On Japanese Tv, The Lady Is A Man Cross-dressing 'onnagata' Are Popul…". 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "From the stage to the clinic: changing transgender identities in post-war Japan". Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- JpopAsia. "Ataru Nakamura - JpopAsia". JpopAsia. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Being Hard Gay for Laughs and Cash". Kotaku. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Television perpetuates outmoded gender stereotypes". Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Model Hiromi comes out as a homosexual : 'Love doesn't have any form, color and rule'" Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, February 18, 2011, Yahoo! News - Yahoo! Japan from RBB Today (in Japanese)

- Min, Yuen Shu (2011-09-01). "Last Friends, beyond friends – articulating non-normative gender and sexuality on mainstream Japanese television". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 12 (3): 383–400. doi:10.1080/14649373.2011.578796. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 144254427.

- For You in Full Blossom - Ikemen Paradise -, retrieved 2019-11-12

- McLelland, Mark J. (2005). Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742537873.

- "The First Lesbian Porn and 10 Other Revealing Artifacts from Lesbian History". VICE. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Male homosexuality in modern Japan: cultural myths and social realities By Mark J. McLelland, p.122; accessed through Google Books

- Bauer, Carola Katharina (2013-05-17). Naughty Girls and Gay Male Romance/Porn: Slash Fiction, Boys' Love Manga, and Other Works by Female "Cross-Voyeurs" in the U.S. Academic Discourses. Anchor Academic Publishing (aap_verlag). ISBN 9783954890019.

Further reading

- Bornoff, Nicholas. Pink Samurai: Love, Marriage & Sex in Contemporary Japan.

- Leupp, Gary. Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1997.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in Japan. |

- "Queer Japan," special issue of Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context

- "Enduring Voices: Fushimi Noriaki and Kakefuda Hiroko's Continuing Relevance to Japanese Lesbian and Gay Studies and Activism," by Katsuhiko Suganuma

- "Telling Her Story: Narrating a Japanese Lesbian Community," by James Welker

- "Japan (GAYCATION Episode 1)." Viceland. February 24, 2016.

- Bibliography of Gay and Lesbian History

- Resource and Support group for LGBT foreigners in Japan "Stonewall AJET"