History of early Tunisia

Human habitation in the North African region occurred over one million years ago. Remains of Homo erectus during the Middle Pleistocene period, has been found in North Africa. The Berbers, who generally antedate by many millennia the Phoenicians and the establishment of Carthage, are understood to have arisen out of social events shaped by the confluence of several earlier peoples, i.e., the Capsian culture, events which eventually constituted their ethnogenesis. Thereafter Berbers lived as an independent people in North Africa, including the Tunisian region.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tunisia |

|

|

|

On the most distant prehistoric epochs, the scattered evidence sheds a rather dim light. Also obscure is the subsequent "pre-Berber" situation, which later evolved into the incidents of Berber origins and early development. Yet Berber languages indicates a singular, ancient perspective. This field of study yields a suggested reconstruction of remote millennia of Berber prehistory, and insight into the ancient cultural and lineage relations of Tunisian Berbers—not only with their neighboring Berber brothers, but with other more distant peoples.

The prehistoric, of course, seamlessly passes into the earliest historic. The first meeting of Phoenician and Berber occurred well to the east of Tunisia, well before the rise of Carthage: a tenth-century invasion of Phoenicia was led by a pharaoh of the Berbero-Libyan dynasty (the XXII) of Ancient Egypt.

In the Maghreb, the first written records describing the Berbers begin with the Tunisian region, proximate to the founding there of Carthage. Unfortunately, surviving Punic writings are very scarce aside from funerary and votive inscriptions; remains of the ancient Berber script is also limited. The earliest written reports come from later Greek and Roman authors. From discovery of archaic material culture and such writings, early Berber culture and society, and religion, can be somewhat surmised.

Tunisia remained the leading region of the Berber peoples throughout the Punic era (and Roman, and into the Islamic). Here modern commentary and reconstructions are presented concerning their ancient livelihood, domestic culture, and social organization, including tribal confederacies. Evidence comes from various artifacts, settlement and burial sites, inscriptions, and historical writings; supplementary views are derived by disciplines studying genetics and linguistics.

People of early North Africa

Pharaohs connected to Egypt by Tunisia

Evidence of habitation in the North African region by human ancestors has been found stretching back one or two million years, yet not to rival those most-ancient finds in south and east Africa.[1] Remains of Homo erectus during the Middle Pleistocene, circa 750 kya (thousands of years ago), has been found in North Africa. These were associated with the change in early hominid tool use form pebble-choppers to hand-axes.[2]

Migrations out of south and east Africa since 100 Kya are thought to have established current human populations worldwide.[3] Cavalli-Sforza includes the Berber populations in a much larger genetic group, one which also includes S.W. Asians, Iranians, Europeans, Sardinians, Indians, S.E. Indians, and Lapps.[4]

"[B]y definition prehistoric archaeology is dealing with pre-written sources only, so that all prehistory is anonymous." Hence, "it is inevitably mainly concerned with the material culture" such as "stone tools, bronze weapons, hut foundations, tombs, field walks, and the like." ... "We have no way of learning the moral and religious ideas of the protohistoric city dwellers... ."[5]

Regarding the evidence of prehistory, very remote epochs often give clues only about physical anthropology, i.e., per biological remains re human evolution. Usually the later millennia progressively disclose more and more cultural information yet, absent writings, it is mostly limited to "material culture". Generally cultural data is considered a far more telling indication of prehistoric human behavior and society, as compared to only evidence of physical human remains.[6]

The cultural data available about human prehistory derived from material artifacts, however, too often directly concerns "non-essentials". It is limited as a useful source about the finer details of archaic human societies—the ethical norms, the individual dilemmas—when compared to the data from written sources. "When prehistorians speak of the ideas and ideals of men before writing, they are making guesses--intelligent guesses by people best qualified to make them, but nevertheless guesses."[7][8]

Perhaps the most significant prehistoric finding worldwide concerns events surrounding the neolithic revolution. Then humans developed significant jumps in cognitive ability. The evidence of the art and expressive artifacts dating back about 10 to 12 kya show a new sophistication in handling experience, perhaps being the fruits of prior advances in the articulation of symbols and language. Herding and farming develop. A new phase of human evolution had begun.[9][10] "The rich heritage of rock painting in North Africa... seem to date after the Pleistocene period... around twelve thousand years ago." Thus a period concurrent with the "neolithic" revolution.[11]

Mesolithic era

Dating to the much more recent Mesolithic era, stone blades and tools, as well as small stone human figurines, of the Capsian culture (named after Gafsa in Tunisia) are associated with the prehistoric presence of Berbers in North Africa. The Capsian is that archaic culture native to the Maghrib region, circa twelve to eight kya. During this period the Pleistocene came to an end with the last ice age, causing changes in the Mediterranean climate. The African shore slowly became drier as the "rain belts moved north".[12] Also related to the Berbers are some of the prehistoric monuments built using very large rocks (dolmens). Located both in Europe and Africa, these dolmens are found at locations throughout the western Mediterranean.[13] The Capsian culture was preceded by the Ibero-Maurusian in North Africa.[14]

Saharan rock art

Saharan rock art, the inscriptions and the paintings that show various design patterns as well as figures of animals and of humans, are attributed to the Berbers and also to black Africans from the south. Dating these art works has proven difficult and unsatisfactory.[15][16] Egyptian influence is considered very unlikely.[17] Some images infer a terrain much better watered. Among the animals depicted, alone or in staged scenes, are large-horned buffalo (the extinct bubalus antiquus), elephants, donkeys, colts, rams, herds of cattle, a lion and lioness with three cubs, leopards or cheetahs, hogs, jackles, rhinoceroses, giraffes, hippopotamus, a hunting dog, and various antelope. Human hunters may wear animal masks and carry their weapons. Herders are shown with elaborate head ornamentation; a few dance. Other human figures drive chariots, or ride camels.[18][19]

Theory of mixed origin

A commonly held view of Berber origins is that Paleo-Mediterranean peoples long occupying the region combined with several other largely Mediterranean groups, two from the east near S.W.Asia and bringing the Berber languages about eight to ten kya (one traveling west along the coast and the other by way of the Sahel and the Sahara), with a third intermingling earlier from Iberia.[20][21][22] "At all events, the historic peopling of the Maghrib is certainly the result of a merger, in proportions not yet determined, of three elements: Ibero-Maurusian, Capsian and Neolithic," the last being "true proto-Berbers".[23]

Cavalli-Sforza also makes two related observations. First, the Berbers and those S.W. Asians who speak Semitic idioms together belong to a large and ancient language family (the Afroasiatic), which dates back perhaps ten kya. Second, this large language family incorporates in its ranks members from two different genetic groups, i.e., (a) some elements of the one listed by Cavalli-Sforza immediately above, and (b) one called by him the Ethiopian group. This Ethiopian group inhabits lands from the Horn to the Sahel region of Africa.[24] In agreement with Cavalli-Sforza's work, recent demographic study indicates a common Neolithic origin for both the Berber and Semitic populations.[25] A widespread opinion is that the Berbers are a mixed ethnic group sharing the related and ancient Berber languages.[26][27]

Perhaps eight millennia ago, already there were prior peoples established here, among whom the proto-Berbers (coming from the east) mingled and mixed, and from whom the Berber people would spring, during an era of their ethnogenesis.[28][29] Today half or more of modern Tunisians appear to be the descendants, however mixed or not, of ancient Berber ancestors.[30]

Berber language history

In the study of languages, sophisticated techniques were developed enabling the understanding of how an idiom evolves over time. Hence, the speech of past ages may be successively reconstructed in theory by using only modern speech and the rules of phonetic and morphological change, and other learning, which may be augmented by and checked against the literature of the past, if available. Methods of Comparative linguistics also assisted in associating related 'sister' languages, which together stem from an ancient parent language. Further, such groups of related languages may form branches of even larger language families, e.g., Afroasiatic.[32][33][34][35][36]

Afroasiatic family

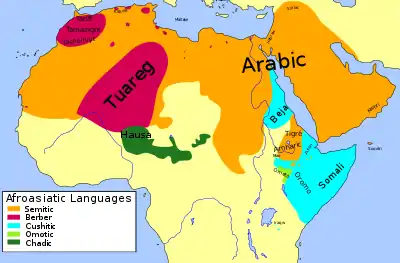

Taken together the twenty odd Berber languages constitute one of the five branches[37][38][39] of Afroasiatic,[40][41][42][43][44][45] a pivotal world language family, which stretches from Mesopotamia and Arabia to the Nile river and to the Horn of Africa, across northern Africa to Lake Chad and to the Atlas Mountains by the Atlantic Ocean. The other four branches of Afroasiatic are: Ancient Egyptian, Semitic (which includes Akkadian, Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, and Amharic), Cushitic (around the Horn and the lower Red Sea),[46] and Chadic (e.g., Hausa). The Afroasiatic language family has great diversity among its member idioms and a corresponding antiquity in time depth,[47][48] both as to the results of analyses in historical linguistics and as regards the seniority of its written records, composed using the oldest of writing systems.[49][50][51] The combination of linguistic studies with other information about prehistory taken from archaeology and the biological sciences has been adumbrated.[52][53] Earlier academic speculation as to the prehistoric homeland of Afroasiatic and its geographic spread centered on a source in southwest Asia,[54][55][56] but more recent work in the various related disciplines has focused on Africa.[57][58][59][60]

Proposed prehistory

The conjecture proposed by linguist and historian Igor M. Diakonoff may be summarized. From a prehistoric homeland near Darfur, which was better watered,[61][62] the "Egyptians" were the first to break from the proto Afroasiatic communities, before ten kya (thousand years ago). These proto Egyptian language speakers headed north. During the next millennium or so, proto-Semitic and -Berber speakers went their divergent ways. The Semites passed by the then marshlands of the lower Nile and crossed into Asia (evidently the Semitic speakers anciently present in Ethiopia remained in Africa or later crossed back to Africa from Arabia). Meanwhile, the peoples who spoke proto-Berbero-Libyan spread out westward across North Africa, along the Mediterranean coast and into a Sahara region then better watered, traveling in a centuries-long migration until reaching the Atlantic and its offshore islands.[63][64][65][66] Later, Diakonoff revised his proposed prehistory, moving the Afroasiatic homeland north toward the lower Nile, then a land of lakes and marshes. This change reflects several linguistic analyses showing that common Semitic then shared very little "cultural" lexicon with the common Afroasiatic.[67] Hence the proto Semitic speakers probably left the common Afroasiatic community earlier, by ten kya (thousand years ago), starting from an area nearby a more fruitful Sinai. Accordingly, he situates the related Berbero-Libyan speakers of that era by the coast, to the west of the lower Nile.[68][69][70]

The early Berbers

Culture and society

By perhaps seven kya (thousand years ago) a neolithic culture was evolving among a coalescence of people, the Berbers, in northwest Africa. Earlier, at the long-occupied cave of Haua Fteah in Cyrenaica, "food gatherers with a Caspian flint industry were succeeded by stock breeders with pottery."[71] Material culture progressed, resulting in animal domestication and agriculture; craft techniques included imprinted pottery, and finely chipped stone implements (evolved from earlier arrowheads).[72]

"The food gatherers who built up the shell middens round the salt lakes of Tunisia were succeeded by simple food producers, with little change in their flint industry... described as a 'Neolithic of Capsian tradition'. [H]ere at least native food gatherers were not displaced by immigrant farmers [from the east] but themselves adopted a food-producing economy. [In the] Maghreb simple farming culture survived very little alterred for millennia. A site with impressed pottery might date to the sixth millennium b.c. or the second."[73]

Wheat and barley were sown, beans and chick peas cultivated. Ceramic bowls and basins, goblets, large plates, as well as dishes raised by a central column, were domestic items in daily use, sometimes hung up on the wall. For clothing findings indicate hooded cloaks, and cloth woven into stripes of different colors. Sheep, goats, and cattle measured wealth.[74] From physical evidence unearthed in Tunisia archaeologists present the Berbers as already "farmers with a strong pastoral element in their economy and fairly elaborate cemeteries", well over a thousand years before the Phoenicians arrived to found Carthage.[75]

Apparently, prior to written records about them, sedentary rural Berbers lived in semi-independent farming villages, composed of small, composite, tribal units under a local leader who worked to harmonize its clans.[76] Management of the affairs in such early Berber villages was probably shared with a council of elders.[77] By particularly fertile regions, the larger villages arose. Yet seasonally the villagers might have left to find the better pasture for their herds and flocks. On the marginal lands, the more pastoral tribes of Berbers roamed widely to find grazing for their animals. Modern conjecture is that feuding between neighborhood clans at first impeded organized political life among these ancient Berber farmers, so that social coordination did not develop beyond the village level, whose internal harmony could vary.[78] Tribal authority was strongest among the wandering pastoralists, much weaker among the agricultural villagers, and would later attenuate further with the advent of cities connected to strong commercial networks and foreign polities.[79]

Throughout the Maghrib (particularly in what is now Tunisia), the Berbers reacted to the growing military threat from colonies started by Phoenician traders. Eventually Carthage and its sister city-states would inspire Berber villages to join together in order to marshall large-scale armies, which naturally called forth strong, centralizing leadership. Punic social techniques from the nearby prosperous cities were adopted by the Berbers, to be modified for their own use.[80][81][82] To the east, the Berbero-Libyans had already interacted with the Egyptians during the millennial rise of the ancient Nile civilization.

Shared heritage

The people commonly known today as the Berbers were anciently more often known as Libyans. Yet many "Berbers" have for long self-identified as Imazighen or "free people" (etymology uncertain).[83] Mommsen, a widely admired historian of the 19th century, stated:

"They call themselves in the Riff near Tangier Amâzigh, in the Sahara Imôshagh, and the same name meets us, referred to particular tribes, on several occasions among the Greeks and Romans, thus as Maxyes at the founding of Carthage, as Mazices in the Roman period at different places in the Mauretanian north coast; the similar designation that has remained with the scattered remnants proves that this great people has once had a consciousness, and has permanently retained the impression, of the relationship of its members."

Other names, according to Mommsen, were used by their ancient neighbors: Libyans (by Egyptians and later by Greeks), Nomades (by Greeks), Numidians (by Romans), and later Berbers (by the Arabs); also the self-descriptive Mauri in the west; and Gaetulians in the south.[84][85]

Several ancient names of Berber polities may be related to their self-designated identity as Imazighen. The Egyptians knew as pharaohs the leaders of a powerful Berber tribe called Meshwesh of the XXII dynasty.[86] Located near Carthage was the Berber kingdom of Massyli, later called Numidia, ruled by Masinissa and his descendants.[87]

Berbers together, with their relations and descendants, have been the major population group to inhabit the Maghrib (North African apart from the Nile) since about eight kya (thousand years ago).[88][89][90][91] This region includes terrain from the Nile to the Atlantic, encompassing the vast Sahara at whose center rise the mountain heights of Ahaggar and Tibesti. In the west the Mediterranean coastlands are suitable for agriculture, having for hinterland the Atlas Mountains. It includes the land now known as Tunisia.

Yet the most ancient written records concerning the Berber peoples are those reported by neighboring peoples of the Mediterranean region. When the Berbers enter history during the first millennium BCE, their own points of view on situations and events are, unfortunately, not available to us. Due to the impact of Carthage, it is the people of Tunisia who dominate the early historical writings on the Berbers.[92]

Accounts of the Berbers

Here described are Berber peoples in the first light of history, drawn from written records left by Egyptians in northeast Africa, and mainly by Greek and Roman authors in northwest Africa. To the east of Tunisia, a Libyan dynasty ruled in Egypt; their armies marched into Phoenicia a century before the founding of Carthage. Next is described Berber life and society in Tunisia and to its west, both before and during the hegemony of Carthage.

Northeast Africa

Egyptian hieroglyphs from early dynasties testify to Libyans, who were the Berbers of Egypt's "western desert"; they are first mentioned directly as the "Tehenou" during the pre-dynastic reigns of Scorpion (c. 3050) and of Narmer (on an ivory cylinder). The Berbero-Libyans later are shown in a bas relief at the temple of Sahure, from the Fifth Dynasty (2487-2348). The Palermo Stone,[93] also called the Libyan Stone, lists the earliest sovereigns of Egypt from the 31st century to the 24th century, i.e., the list includes: about fifty pre-dynastic rulers of Egypt, followed by the earliest pharaohs, those of the first five dynasties. Some conjecture that the fifty earlier rulers listed may be Libyan Berbers, from whom the pharaohs derived.[94]

Much later, Ramses II (r.1279-1213) was known to employ Libyan contingents in his army.[95] Tombs of the 13th century contain paintings of Libu leaders wearing fine robes, with ostrich feathers in their "dreadlocks", short pointed beards, and tattoos on their shoulders and arms.[96]

| Meshwesh (mšwš.w) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Osorkon the Elder (Akheperre setepenamun), a Berber leader of the Meshwesh tribe, appears to be the first Libyan pharaoh. Several decades later his nephew Shoshenq I (r.945-924) became Pharaoh of Egypt, and founder of its Twenty-second Dynasty (945-715).[97][98] In 926 Shoshenq (Shishak of the Bible) successfully campaigned to Jerusalem then under Solomon's heir.[99][100][101] The Phoenicians (particularly the people of the city-state of Tyre, who would later found Carthage during Egypt's Meshwesh dynasty), first came to know of the Berber people through these Libyan pharaohs.

For several centuries Egypt was governed by a decentralized political system loosely based on the Libyan tribal organization of the Meshwesh. Becoming acculturated, much of the evidence shows these Berbero-Libyans through an Egyptian lens. Eventually the Libyans served as high priests at centers of Egyptian religion.[102] Hence during the classical era of the Mediterranean, all of the Berber peoples of North Africa were often collectively called Libyans, due to the fame first won by the Meshwesh dynasty of Egypt.[103][104][105]

Northwest Africa

West of the Meshwesh dynasty of Egypt, later reports of foreigners mention more rustic Berber people by the Mediterranean, living in fertile and accessible coastal regions. Those located in or near Tunisia were known as Numidians; farther to the west, the Berbers were called the Mauri or Maurisi (later the Moors); and, in more remote mountains and deserts to the southwest were Berbers called Gaetulians.[106][107][108] Another group of Berbers in the steppe and desert to the southeast of Carthage were known as the Garamantes.[109]

During the 5th century BC, the Greek writer Herodotus (c.490-425) mentions Berbers as mercenaries of Carthage with regard to specific military events in Sicily, circa 480.[110] Thereafter the Berbers more frequently enter into the early light of history provided by various Greek and Roman historians. Yet unfortunately, apart from the Punic inscriptions, little Carthaginian literature has survived.[111][112] We do know that Mago of Carthage began to employ Berbers as mercenaries in the sixth century.[113]

During these centuries, Berbers of the western regions actively traded and intermingled with Phoenicians, who founded Carthage and its many trading stations. The name 'Libyphoenician' was then coined for the cultural and ethnic mix surrounding Punic settlements, particularly Carthage. Political skills and civic arrangements encountered in Carthage, as well as material culture, such as farming techniques, were adopted by the Berbers for their own use.[114][115] In the 4th century, Berber kingdoms are referenced, e.g., the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus evidently mentions the Libyo-Berber king Aelymas, a neighbor to the south of Carthage, who dealt with the invader Agathocles (361-289), a Greek ruler from Sicily.[116][117] Berbers here operated independently of Carthage.

Circa 220 BC, three large kingdoms had arisen among the Berbers. These Berbers, independent yet markedly influenced by Punic civilization, had nonetheless endured the long ascendancy of Carthage. West to east the kingdoms were: (1) Mauretania (in modern Morocco) under the Mauri king Baga; (2) the Masaesyli (in north Algeria) under their king Syphax who then ruled from two capitals, in the west Siga (near modern Oran) and in the east Cirta (modern Constantine); and (3) the Massyli (south of Cirta, directly west and south of nearby Carthage) ruled by king Gala [Gaia], father of Masinissa. Following the Second Punic War, Massyli and eastern Masaesyli were joined to form Numidia, located in historic Tunisia. Both Roman and Hellenic states gave its famous ruler, Masinissa, honors befitting esteemed royalty.[118]

Ancient Berber religion

Evidence of ancient Berber religion and sacred practices provide some views, however incomplete, of the interior life of the people, otherwise largely opaque, and thus also clues as to the character of the Berbers, who witnessed the founding of Carthage.

Respect for the dead

The religion of the ancient Berbers, of course, is difficult to uncover sufficiently to satisfy the imagination. Burial sites provide early indication of religious beliefs; more than sixty thousand tombs are located in the Fezzan alone.[121] The construction of many tombs indicates their continuing use for ceremonies and sacrifices.[122] A grand tomb for a Berber king, traditionally assigned to Masinissa (238-149) but perhaps rather to his father Gala, still stands: the Medracen in eastern Algeria. Architecture for the elegant tower tomb of his contemporary Syphax shows some Greek or Punic influence.[123] Much information about Berber beliefs comes from classical literature. Herodotus (c. 484-c. 425) mentions that Libyans of the Nasamone tribe, after prayers, slept on the graves of their ancestors in order to induce dreams for divination. The ancestor chosen being regarded the best in life for uprightness and valor, hence a tomb imbued with spiritual power. Oaths also were taken on the graves of the just.[124][125] In this regard, the Numidian king Masinissa was widely worshipped after his death.[126]

Reverence for nature

Early Berbers beliefs and practices are often characterized as a religion of nature. Procreative power was symbolized by the bull, the lion, the ram. Fish carvings represented the phallus, a sea shell the female sex, which objects could become charms.[127][128] The supernatural could reside in the waters, in trees, or come to rest in unusual stones (to which the Berbers would apply oils); such power might inhabit the winds (the Sirocco being formidable across North Africa).[129] Herodotus writes that the Libyans sacrificed to the sun and moon.[130] The moon (Ayyur) was conceived as being masculine.[131][132]

Later many other supernatural entities became identified and personalized as gods, perhaps influenced by Egyptian or Punic practice; yet the Berbers seemed to be "drawn more to the sacred than to the gods."[133] Early worship sites might be in grottoes, on mountains, in clefts and cavities, along roadways, with the "altars casually made of turf, the vessels used still of clay with the deity himself nowhere", according to the Berber author Apuleius (born c. 125 CE), commenting on the local worship of earlier times.[134] Often only a little more than the names of the Berber deities are known, e.g., Bonchar, a leading god.[135] Julian Baldick, culling literature covering many eras and regions, provides the names and rôles of many Berber deities and spirits.[136][137]

Syncretic developments

The Berbero-Libyans came to adopt elements from ancient Egyptian religion. Herodotus writes of the divine oracle, sourced in the Egyptian god Ammon, located among the Libyans at the oasis of Siwa. This Libyan oasis of Ammon functioned a sister oracle to one at Dodona in Greece, according to Herodotus (c.484-c.425).[138][139] However, the god of the Siwa oracle, to the contrary, may be a Libyan deity.[140] The visit of Alexander in 331 brought to the Siwa oracle wide notice in the ancient world.[141]

Later, Berber beliefs would influence the Punic religion from Carthage, the city-state founded by Phoenicians.[142] George Aaron Barton suggested that the prominent goddess of Carthage Tanit originally was a Berbero-Libyan deity whom the newly arriving Phoenicians sought to propitiate by their worship.[143][144] Later archeological finds show a Tanit from Phoenicia.[145][146][147] From linguistic evidence Barton concluded that before developing into an agricultural deity, Tanit probably began as a goddess of fertility, symbolized by a tree bearing fruit.[148] The Phoenician goddess Ashtart was supplanted by Tanit at Carthage.[149][150]

See also

References

- L. Bailout, "The prehistory of North Africa" 241-250, at 241, in General History of Africa, volume I, Methodology and African Prehistory Abridged Edition. (University of California/UNESCO 1989).

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistory of the Mediterranean (Yale University 1980) at 10.

- Christopher Stringer and Robin Mickie, African Exodus. The origins of modern humanity (New York: Henry Holt 1996), e.g., DNA tree at 137, 'genetic distances' graph at 147, map at 178.

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, & Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton University 1994) at 99.

- Glyn Daniel, The Idea of Prehistory (London: C. A. Watt 1962; reprint Penguin 1964) at 131-132.

- Cf., E. Adamson Hoebel, Man in the Primitive World (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2d ed. 1958), at 147: "[S]o slight in their apparent effect on human behavior... race differences are of such relative insignificance as to be of no functional importance. Culture, not race, is the great molder of human society." Pharaohs Connected to the tunis.

- Glyn Daniel, The Idea of Prehistory (London: C. A. Watt 1962; reprint Peguin 1964) at 132.

- Cf., Harold Goad, Language in History (Penguin 1958) at 11-14.

- Colin Renfrew, Prehistory. The making of the human mind (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2007, reprint: Modern Library, New York, 2009) at 70-72, 86-88, 91-95. Renfrew calls this new phase the tectonic. He suggests that evolution by genetics now fades in importance, as henceforth human development will be sourced in learning and invention transmitted to future generations by culture. Ibid. at 82-83. [Renfrew, e.g., at 72, 85, dates this tectonic revolution to about 10 kya, and excepts the 40 kya paleolithic cave art of France and Spain.]

- Cf., Peter J. Richerson and Robert Boyd, Not by Genes Alone. How culture transformed human evolution (University of Chicago 2005), e.g., at 8-10, 103-106.

- Renfrew, Prehistory (2007, 2009) at 72.

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistory of the Mediterranean (Yale University 1980) at 20 (Caspian), 19 (weather). The cave Haua Fteah at Cyrenaica to the east of Tunisia gives evidence of use by Mousterian culture at its lower levels, circe 40,000 kya. Trump (1980) at 19, and cf. 55.

- Brent, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 10–13, 17–22, map of dolmen regions at 17. The dolmens are found both north and south of the Mediterranean Sea.

- J. Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" at 236-245, 236-238, in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Paris: UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- Lloyd Cabot Briggs, Tribes of the Sahara (Harvard Univ. & Oxford Univ. 1960) at 38-40.

- P. Salama, "The Sahara in Classical Antiquity" at 286-295, 291, in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- Julian Baldick, Black God (Syracuse University 1997) at 67.

- C.B.M.McBurney, The Stone Age of Northern Africa (Pelican 1960) at 258-266.

- J.Ki-Zerbo, "African prehistoric art" at 284-296, 286, in General History of Africa, volume I, Methodology and African Prehistory (UNESCO 1989), Abridged Edition.

- Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton 1977) at 17, 60 (re S.W.Asians, referencing the earlier work of Gsell).

- L. Balout, "The prehistory of North Africa" 241-250, at 245-250, in General History of Africa, volume I, Methodology and African Prehistory Abridged Edition. (University of California/UNESCO 1989).

- Camps, Gabriel (1996). Les Berbères. Edisud. pp. 11–14, 65. Camps has an influx at eight kya (thousand years ago), with an earlier Iberian prospering at twelve kya.

- J. Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" 236-245, at 237, in General History of Africa, v.II Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990).

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, & Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton University 1994) at 99. Notwithstanding this genetic distinction, there is overlap. E.g., it is suggested that the Tuareg Berbers are genetically linked to the "Ethiopian" Beja (ancient Blemmyes) of the Red Sea Hills area of the Sudan; in coming west into the central Sahara, the Tuareg may have shed their Cushitic idiom and adopted the related Berber speech. Cavalli-Sforza (1994) at 172-173. See below, "Berber language history" for discussion regarding Afroasiatic.

- "Our analyses suggest that contemporary Berber populations possess the genetic signature of a past migration of pastoralists from the Middle East and that they share a dairying origin with Europeans and Asians, but not with sub-Saharan Africans". Sean Myles, Nourdine Bouzekri, Eden Haverfield, Mohamed Cherkaoui, Jean-Michel Dugoujon, Ryk Ward, "Genetic Evidence in support of a shared Eurasian-North African dairying origin" in Human Genetics (Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer 2005) 117/1: 34-42, "Abstract" at 34. SpringerLink - Journal Article

- Mário Curtis Giordani, História da África. Anterior aos descobrimentos (Petrópolis, Brasil: Editora Vozes 1985) at 42-43, 77-78. Giordani references Bousquet, Les Berbères (Paris 1961).

- Also see infra, "Berber language history" re Afroasiatic, in particular Diakonoff's discussion about prehistoric populations.

- Camps, Gabriel (1996). Les Berbères. Edisud. pp. 11–14.

- Brett and Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 14–15.

- Gerard and others, "North African Berber and Arab Influences in the Western Mediterranean Revealed by Y-Chromosome DNA Haplotypes" (2006).

- Cf., Joseph R. Applegate, "The Berber Languages" at 96-118, 96-97, in Afroasiatic. A Survey (1971).

- Robert Lord, Comparative Linguistics (London: English Universities Press 1966) at 67-105 (phonetics), 135-164 (morphology and syntax).

- Holgar Pedersen, Sprogvidenskaben i det Nittende Aarhundrede: Metoder og Resultater (Kobenhavn: Gyldendalske Boghandel 1924), translated as The Discovery of Language. Linguistic science in the 19th century (Cambridge: Harvard University 1931, reprint Midland 1962) at 1-19, 116-124 ("Semitic and Hamitic").

- Merrit Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages (Stanford University 1987), Afroasiatic at 85-95.

- Robert Hetzron, "Afroasiatic Languages", 645-723, especially 647-653, in Bernard Comrie, editor, The World's Major Languages (Oxford University 1990). Includes: Hetzron, "Semitic languages" at 654-663; Alan S. Kaye, "Arabic" at 664-685; and, Hetzron, "Hebrew" at 686-704.

- Nicolas Ostler, Empires of the Word. A language history of the world (HarperCollins 2005). Map of Afroasiatic at 36.

- Within Afroasiatic, Bender classifies the Berber languages with Ancient Egyptian and the Semitic languages in a Northern Afroasiatic group; two other linguists, Fleming and Newman, classify it with Chadic; others, e.g., Hetzron, are noncommittal. Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages. Volume 1: Classification (Stanford Univ. 1987) at 90-91.

- Within Afroasiatic, Diakonoff supports a Berbero-Libyan and Semitic proximity. I. M. Diakonoff, Semito-Hamitic Languages (Moscow: Nauka 1965) at 102, 104; and his Afrasian Languages (Moscow: Nauka 1988) at 24, but see per Chadic and Egyptian at 20.

- Although in some Afroasiatic branches the connections are loose, Semitic and Berber each are "close-knit" branches "whose internal unity cannot be questioned." Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages (Stanford Univ. 1987) at 89. Of course, Ancient Egyptian is a branch with a single member language.

- Robert Hetzron, "Afroasiatic Languages" at 645-653, in Bernard Comrie, The World's Major Languages (Oxford Univ. 1990). Hetzron discusses the Berber languages within Afroasiatic at 648.

- M. Lionel Bender, "Afrasian Overview" at 1-6, in Selected Comparative-Historical Afrasian Linguistic Studies in memory of Igor M. Diakonoff, edited by M. Lionel Bender, Gabor Takacs, and David L. Appleyard (Muenchen: LINCOM 2003).

- Greenberg, Joseph (1966). The Languages of Africa. Indiana University. pp. 42, 50.

- Crystal, David (1987). Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. pp. 316.

- Carleton T. Hodge, "Afroasiatic: An Overview" at 9-26, in Hodge (ed.), Afroasiatic. A Survey (1971).

- Marcel Cohen, Essai comparatif sur le vocabulaire et la phonétique du chamio-sémitique (Paris: Champion 1947).

- A new branch has been proposed, Omotic, composed of languages until then considered within the Cushitic branch. M. Lionel Bender, Omotic. A New Afroasiatic Language Family (Univ. of Southern Illinois 1975).

- I. M. Diakonoff, Afrasian Languages (1988) at 16, referencing "the much earlier date of the break-up of the Afrasian proto-language, as compared with the Proto-Indo-European."

- Regarding Berber, Cavalli-Sforza refers to possible dates up to seventeen kya for the Berber ancestor's split from Indo-European language speakers. Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, & Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. 1994) at 103, apparently citing A.B. Dolgopolsky, "The Indo-European homeland and lexical contacts of Proto-Indo-European with other languages" in Mediterranean Language Review 3: 7-31 (Harrassowitz 1988).

- Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs (c.3000) were probably developed shortly after cuneiform (c.3100), and are the oldest Afroasiatic writings known. I. J. Gelb, A Study of Writing (Univ.of Chicago 1952, 2nd ed. 1963) at 60.

- The inventors of the first writing system, cuneiform, were the Sumerians who spoke a non-Afroasiatic language in Mesopotamia; yet several centuries later it was adopted there by the Akkadians who spoke a Semitic language. Geoffrey Sampson, Writing Systems. A linguistic introduction (Stanford Univ. 1985) at 46-47, 56.

- Afroasiatic language speakers of the Proto-Canaanite group, with help from a secondary syllabary developed by the Egyptians, are credited with the invention of the alphabet. John F. Healey, The Early Alphabet (British Museum 1990) at 16-18.

- Patrick J. Munson, "Africa's Prehistoric Past" at 62-82, 78-81 (subtitled: 'Correlations of Archaeology and African Languages'), in Africa, edited by Phyllis M. Martin and Patrick O'Meara (Indiana Univ. 1977). Perhaps the cultural antecedents of Afroasiatic may be traced back twenty kya (thousands of years ago). Ibid., at 81.

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, & Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. 1994), who compare their research results with population groups connected with language families derived from linguistics (although with the caveat that language speakers and genetic groups are distinct categories). "Comparison with linguistic classifications" at 96-105. A brief outline of Afroasiatic is given at 165. Three book reviews appear in Mother Tongue at Issue 24: 9-29 (1995).

- Cf., Holger Pedersen, The Discovery of Language. Linguistic Science in the 19th Century (Harvard Univ. 1931, reprint Midland Book 1962) at 116-124. Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) first proposed the term Semitic; later Hamitic was named after another son of Noah in the tenth chapter of Genesis. Ibid. (1962) at 118. Hence Hamito-Semitic, the prior name for Afroasiatic.

- Afroasiatic had been termed Hamito-Semitic because of the erroneous view that besides the Semitic branch, the other four groups were similar and related, i.e., the so-called Hamitic branch (Ancient Egyptian, Berber, Cushitic, and Hausa). Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages. Volume 1: Classification (Stanford Univ. 1987) at 85-95, 88.

- It had long been suggested that there were linguistically five equal and independent branches of this language family. Eventually this was sufficiently demonstrated by Greenberg, and the term Afroasiatic was coined. Joseph Greenberg, The Languages of Africa (Indiana Univ. 1963, 3rd ed. 1970) at 49-51. Although an obvious advance in language classification, the new name was misleading in that only a small fraction of Asia and less than half of Africa speaks or spoke an Afroasiatic language. Yet it does straddle the two continents.

- Igor Mikhailovich Diakonoff, Afrasian Languages (Moscow: Nauka Publishers 1988) at 21-24; and his earlier Semito-Hamitic Languages (Moscow: Nauka 1965) at 102-105, followed by three Maps. Diakonoff situates the homeland in the southeast Sahara, between Tibesti and Darfur, when it was well watered during the Mesolithic period, i.e., before nine kya (thousand years ago). Ibid. (1988) at 23. The contraction Afrasian was invented to avoid the misleading geographical implications of Afroasiatic.

- M. Lionel Bender, Omotic (1975) at 220-225, with Map. Bender discusses and differs with Diakonoff (1965). Bender situates the Afroasiatic homeland in or around the upper Nile. Ibid. at 220-221, 225. Bender mentions that language homelands are generally proximous to the area of the most diverse linguistic phenomena. Ibid. at 223. The upper Nile is between the complex branches of Chadic and Cushitic (and the proposed Omotic), and is also nearby the many ancient varieties of Semitic spoken in Ethiopia. Cf., Bender, "Upside-Down Afrasian" in Afrikanistisches Arbeitspapiere 50: 19-34 (1997).

- Carleton T. Hodge, "Afroasiatic: The Horizon and Beyond", in The Jewish Quarterly Review, LXXIV: 137-158 (1983) at 152. He favors the Central Nile, citing Diakonoff, "Earliest Semites in Asia" in AOF 8: 23-74 (1981), and the Munson article in the book Africa (Indiana Univ. 1977).

- Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 14–15.

- At about this time the surface water level of Lake Chad to the west was 12 meters higher than it is today. R. Said, "Chronological framework: African pluvial and glacial epics" at 146-166, 148, in General History of Africa, volume I, Methodology and African Prehistory (UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- A drying out of the Sahara during the fourth and third millennium B.C.E. (6 kya to 4 kya) is accounted for and described by the Sahara Pump Theory, in its most recent cycle.

- I. M. Diakonoff, Afrasian Languages (Moscow: Nauka Publishers 1988) at 23-24.

- As opposed to Diakonoff, Alexander Militarev links Afroasiatic with the Natufian culture in prehistoric Levant, and thus also locates the Afroasiatic homeland there. Cf., Diakonoff (1988) on Militarev at 24-25; and, Gabor Takacs, "Marginal Remarks on the Classification of Ancient Egyptian within Afro-Asiatic and its Position among African Languages" in Folia Orientalia 35: 175-196 (1999) at 186, discussing Militarev.

- Cf., Stéphane Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1914-1928), e.g., I: 275-308.

- Guanche (said to be extinct), spoken in the Canary Islands is classified as a Berber language. Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages (Stanford Univ. 1987) at 92, 93.

- I. M. Diakonoff, Journal of Semitic Studies (1998) at v.43: 209, 210, 212, cites a series of studies by Pelio Fronzaroli, Studi sul lessico comune semitico (Rome 1964-1969), which discusses (1) parts of the body, (2) exterior phenomena, (3) religion and mythology, (4) wild nature, and (5) domesticated nature; Diakonoff also cites Vladimir E. Orel and Olga V. Stolbova, Hamito-Semitic Etymological Dictionary: Materials for Reconstruction (Leiden: E.J.Brill 1994), which he warns to use with caution; and, Diakonoff's own "Earliest Semites in Asia: Agricultural and Animal Husbandry, According to Linguistic Data (8th-4th Millennia B.C.)" in Altorientalische Forschunden (Berlin 1981) 8: 23-74. He states, "Of the hundreds of CS [Common Semitic] cultural terms collected... hardly any prove to be Common Afroasiatic!" Journal of Semitic Studies (1998) at 43: 213.

- I. M. Diankonoff, "The Earliest Semitic Community. Linguistic Data" in Journal of Semitic Studies XLIII/2: 209-219 (1998), at 213, 216-219. Diakonoff at 219 mentions the Jericho culture (ten-nine kya) as being Semitic.

- This revision by Diakonoff would seem to imply that the varieties of Semitic languages anciently spoken in Ethiopia arrived back in the Horn of Africa via south Arabia.

- The speculation may be entertained that the Semitic-speakers in crossing Sinai encountered in the Natufian (pre-eleven kya) a more advanced material and spiritual culture, yet that their own Semitic language proved the better able in understanding, communicating, and negotiating the novel social situations arising (if not also during an aftermath of conquest). The ensuing complexity and protracted merger of these two prehistoric human groups eventuated in their speaking common Semitic yet with a lexicon derived from Natufian material and spiritual culture. If such a counter-intuitive syncretism is accepted, Diakonoff's 1988 conjecture might remain viable. The apparent fragility of the various conjectures illustrates the degree of cognitive fog covering these prehistoric landscapes.

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistoric Mediterranean (Cambridge University 1980) at 19, 55 (Haua Fteah); quote at 55.

- Lloyd Cabot Briggs, Tribes of the Sahara (Harvard Univ. & Oxford Univ. 1960) at 34-36.

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistoric Mediterranean (1980), quote at 56; beginnings of farming in the near east at 22-27.

- J. Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" 236-245, at 241-243, in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. p. 16..

- Soren, Ben Khader, Slim, Carthage (Simon and Schuster 1990) at 44-45.

- Brent D. Shaw, "The structure of local society in the early Maghrib: the elders", essay III, 18-54, at 23-26, in Rulers, Nomads, and Christians in Roman North Africa (Aldershot: Variorum/Ashgate 1995).

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 33-34 (villages and clans), at 135 (semi-pastoral).

- Cf., Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton 1977) at 64.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 24-25 (adaptation of Punic political skills).

- Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton 1977) at 61-62 (Phoenician pressure).

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistory of the Mediterranean (Yale University 1980) at 55-57.

- Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 5–6.

- Theodor Mommsen, Römanische Geschichte, volume 5 (Leipzig 1885, 5th ed. 1904), translated as The Provinces of the Roman Empire (London: R. Bentley 1886; London: Macmillan 1909; reprint: Barnes and Noble, New York 1996) at II: 303, 304. By ancient Mauretania Mommsen here would be refetring to present-day Morocco.

- The ancient Greeks regularly called various people whose speech they could not understand "barbarians", which evidently was adopted here by the Arabs a millennium later.

- See below section entitled Accounts of the Berbers.

- See section Accounts of the Berbers at "Northwest Africa".

- Camps, Gabriel (1996). Les Berbères. Edisud. pp. 11–14, 65. Camps posits a new influx around 6000 B.C. that joined a pre-existing population (an archeologist, Camps founded the Institut d'Etudes Berberes at the Université de Aix-en-Provence).

- Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 5, 12–13. Brett and Fentress refer to Gabriel Camps at 7, 12, 15-16.

- Professor Jamil Abun-Nasr mentions the arrival of the Libou (Libyans) up to 5000 years ago, in his A History of the Maghrib (Cambridge University 1971) at 7.

- McBurney, C. B. M. (1960). The Stone Age in North Africa. Pelican. p. 84.

- Laroui, Abdallah (1977) [1970]. L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthesis (translated as: The History of the Maghrib). Librairie François Maspero; Princeton Univ. pp. 3–26. Professor Laroui here laments that until well into the period of ancient history the story of the indigenous people was told by their antagonists, because the Berbers themselves then left no writings. Thus the ancient point of view of the Berbers is little known; rather they appear as "pure object and can be seen only through the eyes of foreign conquerors". Laroui (1970, 1977) at 10. In this regard, Laroui criticizes several French historians, including Gabriel Camps cited above, not for their research results, but because Laroui finds they continue to portray the Berbers as marginalized in terms of their history. Ibid., at 15-25, 23-25, 60n43.

- Named for the Museo Archeologico Regionale in Palermo, where much of it is kept.

- Helene F. Hagan, "Book Review" Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine of Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), at paragraph "a".

- J. Desanges, "The proto-Berbers", in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Univ.of California/UNESCO 1990), Abridged Ed., 236-245, at 238-240.

- Brent, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell. pp. 22, illustration at 23.

- Erik Hornung, Grunzüge der äegyptischen Geschichte (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche 1978), translated as History of Ancient Egypt (Cornell Univ. 1999) at xv, 52-54; xvii-xviii, 128-133. In 818 the ruling Bubastid house split, both of its Berber Meshwesh branches continuing to rule, one later called the 23rd Dynasty. Hornung (1978, 1999) at 131.

- Almost two millennia later a Fatimid Berber army would again occupy Egypt from the west, and establish a dynasty there. See History of early Islamic Tunisia#Fatimids: Shi'a Caliphate.

- 2nd Chronicles 12:2-9.

- Erik Hornung, History of Ancient Egypt (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche 1978; Cornell University 1999) at 129.

- D. H. Trump, The Prehistory of the Mediterranean (Yale University 1980) at 228 (Libya and Egypt), 229 (Solomon's temple).

- Erik Hornung, History of Ancient Egypt (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche 1978; Cornell University 1999) at 129, 131

- Welch, Galbraith (1949). North African Prelude. Wm. Morrow. p. 39.

- Abun-Nasr (1971). A History of the Maghrib. Cambridge University. p. 7.

- Cf., Herodotus (c.484-c.425), The Histories IV, 167-201 (Penguin 1954, 1972) at 328-337; and per the Garamantes of the Libyan desert (the Fezzan) at 329, 332.

- Strabo (c. 63-A.D. 24). Geographica. pp. XVIII, 3, ii.; cited by René Basset, Moorish Literature (Collier 1901) at iii.

- Cf., Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton 1977) at 65.

- Yet the names Mauri and Moor have been used by ancient and medieval authors to designate also black Africans coming from south of the Sahara. Frank M. Snowden, Jr., Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience (Harvard University 1970) at 11-14.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 22-24.

- According to Herodotus (c. 490-425), The Histories at VII, 167; translated by Audrey de Selincourt, revised by A.R.Burn (Penguin 1954, 1972) at 499.

- B. H. Warmington, "The Carthiginian Period", in General History of Africa, volume III. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), 246-260, at 246.

- Carthage's long and frequent interaction with the Berber peoples surrounding them, are not known to us from their accounts because we possess no Punic writings. Serge Lancel, Carthage. A History (Oxford: Blackwell 1992, 1995) at 358-360.

- Warmington, "The Carthiginian Period", in General History of Africa, volume III. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), 246-260, at 248.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 34.

- Gabriel Camps, Les Berbères (Edisud 1996) at 19-21.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 25, 287.

- Diodorus Siculus (first century B.C.E., historian of Sicily [Siculus]), his Bibliothecae Historicae at xx, 17.1, 18.3; cited by Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers (1981) at 14.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 24-27 (kingdoms).

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 127, 129.

- Cf. Mohammed Chafik, "Elements lexicaux Berberes pouvant apporter un eclairage dans la recherche des origines prehistoriques des pyramides" in Revue Tifinagh ##11-12: 89-98 (1997).

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 23.

- Gabriel Camps, Monuments et rites funéraires protohistoriques (Paris: Arts & Métiers Graphiques 1961), cited in Baldick, Black God. Afroasiatic roots of the Jewish, Christian and Muslim religions (1997) at 68-69; and generally his chapter 3 "North Africa" at 67-91.

- Tomb of Syphax is at Siga near Oran. Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 27-31.

- Herodotus (c.484-c.425), The Histories IV, 172-174 (Penguin 1954, 1972) at 329 (divination).

- J.A.Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers. A Study of Social Evolution in Ancient North Africa (Ibadan Univ. 1981) at 118, 122-123, referencing also Tertullian (160-c.230) of Carthage, his Apologia at 5.1.

- Masinissa was venerated not so much as divine but "because they recognized his greatness and his merit which had an element of the divine." Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers (1981) at 124, citing the third-century Roman Christian author (probably of North Africa) Minucius Felix, Octavius at 21.9.

- J.Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" at 236-245, 243, in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- Cf. Baldick, Black God (1997) at 72, 78, 79, 81. Here Baldick mentions instances where a limited sexual license has been allowed annually on a calendar day determined by the season and the stars or phase of the moon.

- Baldick, Black God (1997) at 70, 72, 73.

- Herodotus (c.484-c.425), Istoreia, IV 188, translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt, revised by A.R.Burn, as The Histories (Penguin 1954, 1972) at 333-334 (sun and moon).

- Julian Baldick, Black God: Afroasiatic Roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Religions (London: I.B.Tauris 1997) at 20 (Semitic moon god, sun goddess), 70 (sun and moon worshipped by Berbers), 74 (another Berber moon god, Ieru), 89-91 (Berber religion within the Afroasiatic). See below Berber language history regarding Afroasiatic.

- Cf., Brian Doe, Southern Arabia (New York: McGraw-Hill 1971) at 25 (moon god ['LMQH], sun goddess Dhat Hamym).

- J.Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" at 236-245, 243-245, 245, in General History of Africa, volume II. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990), Abridged Edition.

- Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers (1981) at 121, quoting the Roman-era Berber writer Apuleius, his Apologia 25, 13.

- There is a third-century AD relief from ancient Vaga (now Béja, Tunisia), with Latin inscription, which shows seven Berber gods (the Dii Mauri or Mauran gods) seated on a bench: Bonchar in the center with a staff (master of the pantheon), to his right sits the goddess Vihina with an infant at her feet (childbirth?), to her right is Macurgum holding a scroll and a serpent entwined staff (health?), to Bonchar's left is Varsissima (without attributes), and to her left is Matilam evidently presiding over the sacrifice of a boar; at the ends are Macurtan holding a bucket and Iunam (possibly the moon). Aicha Ben Abad Ben Khader and David Soren, Carthage: A Mosaid of Ancient Tunisia (American Museum of Natural History 1987) at 139-140.

- Baldick, Black God: Afroasiatic Roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Religions (London: I.B.Tauris 1997) at chapter 3, "North Africa". From Tertullian: Varsutina, chief goddess of Mauri (at 72); from inscriptions: the god Baccax, object of pilgrimages (at 73-74), Ieru, moon god (74), Lilleu, male personification of rain water (74); from a Byzantine source: Gurzil, bull god with stone idol (74-75), Sinifere, war god (74), Mastiman, infernal deity, to whom human sacrifices made (74); late medieval Canary Islands: the god Eraoranzan, worshipped by men (77), the goddess Moneyba, venerated by women (74), Idafe, worshipped as a tall thin rock (77); spirits from modern sources: Imbarken, Saharan spirits who controlled the winds (79), Tenunbia, female being represented by dolls, used to invoke the rain (79), Anzar, male personification of rain (89). Also mentioned are Amun-Re of Egypt (67), Tanit of Carthage (at 71, 74, 79), or those given Roman names (Caelestis at 74, 79), or Arabic names (e.g., the devils Shamarikh at 75).

- J.A.Ilevbare from inscriptions gives the Berber names of many gods in his Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers (1981) at 120. At specified places: Bocax, Auliswa, Mona, Mathamos, Draco, Lilleus, Abaddir; and five gods together near Theveste: Masiden, Thililva, Suggan, Iesdan, and Masiddica. Sinifere, a war god (compared to Mars). Mastina, who received human sacrifice (compared to Jupiter). Gurzil, personified as a "magical" bull let loose in battle, hence a war god.

- Herodotus, The Histories II, 55-56 (Penguin 1954, 1972) at 153-154.

- Evidently, there was seven sacred oracles to the ancient Greeks, and Siwa was the only one in a foreign land. Galbraithe Welch, North African Prelude (New York: Wm. Morrow 1949) at 93.

- J. A. Ilevbare in his Carthage, Rome, and the Berbers (Ibadan Univ. 1981) at 117-118, states that there was a Libyan god Ammon concerned with divination whose oracle was at the Siwa oasis, this god being apart from the Egyptian god of Thebes also called Ammon or Amun. His sources include Oric Bates, The Eastern Libyans (London: 1914; reprint Cass 1970) at 189-191.

- Ulrich Wilcken, Alexander der Grosse (Leipzig 1931), translated as Alexander the Great (New York: W. W. Norton 1967) at 121-130. At Siwa the Egyptian priests told Alexander he was the son of 'Zeus Ammon'. Wilcken (1931, 1967) at 126-128.

- Soren, Ben Khader, Slim, Carthage (New York: Simon and Schuster 1990) at 26-27 (fusion with Tanit), 243-244.

- George Aaron Barton, Semitic and Hamitic Origins. Social and Religious (Philadelphia: Univ.of Pennsylvania 1934) at 303-306, 305.

- "The name is apparently Libyan" in reference to the goddess Tanit: B.H.Warmington, "The Carthaginian Period" at 246-260, 254, in General History of Africa, volume II, Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990).

- Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2000) at 118, where Markoe notes, "The discovery at Sarepta of an inscribed ivory plaque dedicated to Tanit-Astarte... [affirms] the mainland origin of the former goddess, whose cult achieved enormous popularity at Carthage and the Punic west, beginning in the fifth century B.C." The Sarepta site (located on the Phoenician coast between Tyre and Sidon) was explored by archeologists in the 1970s; the plaque is said to date to eighth century B.C. The goddess Astarte was a major deity at Tyre.

- Cf., Picard, "The Life and Death of Carthage" (1968-1969) at 151-152.

- Cf., E. A. Wallis Budge, Osiris. The Egyptian Religion of Resurrection (London: P.L.Warner 1911; reprint University Books 1961) at II: 276-277; Budge quotes a text dating to the "New Empire" [Budge's term, the New Kingdom is dated 1550-1070] which praises the Egyptian goddess Isis: "She of many names. ... She who filleth the Tuat with good things. She who is greatly feared in the Tuat. The great goddess in the Tuat with Osiris in her name Tanit." Here the Tuat would be the region where "spirits departed after the death of their bodies." Budge, ibid. at II: 155. It may have a remote relation to the Berber oasis of Tuat (In Salah) located in south central Algeria.

- Barton, Semitic and Hamitic Origins (1934) at 305.

- See History of Punic era Tunisia#Punic religion.

- See also History of early Islamic Tunisia regarding its probable influence on the received Muslim practice.