History of Burnley F.C.

Burnley Football Club is an English professional association football club based in Burnley, Lancashire, that was founded on 18 May 1882. The club became professional in 1883 – one of the first clubs to do so – putting pressure on the Football Association (FA) to permit payments to players. As a result, the club was able to enter the FA Cup for the first time in 1885–86 and was one of the 12 founding members of the Football League in 1888–89.

The team struggled in the early years of the Football League; they were relegated to the Second Division at the end of the 1896–97 season. Burnley achieved promotion back to the First Division in 1913; the following year they won the FA Cup for the first – and to date only – time, defeating Liverpool in the final. In the 1920–21 campaign, Burnley were crowned champions of England for the first time. During that season they embarked on a 30-match unbeaten run, a then-English record. Burnley remained in the top tier of English football until 1930, when they sank to the second tier and stayed there until 1947.

Burnley won a second league championship in 1959–60 with a last-day victory over Manchester City. Between 1970 and 1983, Burnley were yo-yoing between the first and third tiers, and in 1985, they were relegated to the Fourth Division for the first time. In 1987, a last-day win against Orient prevented relegation to the Football Conference. The team won the fourth tier in 1992 to become the second team to win all four professional divisions of the English football league system. They were promoted to the second tier in 2000 and to the Premier League in 2009, 2014 and 2016.

Early years (1882–1912)

On 18 May 1882, members of Burnley Rovers gathered at the Bull Hotel in Burnley to vote for a change from rugby to association football, following other sports clubs in the area that had changed code to football.[1] A large majority voted in favour of the proposed change of sport. The club secretary George Waddington met with his committee a few days later and forward a proposal to drop "Rovers" from the club's name, thereby "adopting the psychological high ground over many other local clubs by carrying the name of the town", to which the committee members unanimously agreed.[1]

On 10 August, Burnley Football Club played and won their first-ever match as an association football club against local team Burnley Wanderers 4–0. The team played the match in a blue and white kit – the colours of the former rugby club – at their home ground Calder Vale, which was also inherited from the rugby club.[2][3] The club's first competitive game was in October 1882 against Astley Bridge in the Lancashire Cup, which ended in an 8–0 defeat.[2] In February 1883, the club was invited by Burnley Cricket Club to move to a pitch adjacent to the cricket field at Turf Moor;[4][5] both clubs have remained there since and only Lancashire rivals Preston North End have continuously occupied the same ground for longer.[5][6]

That same year saw the team win their first trophy. In January 1883, Dr Thomas Dean, Burnley's Medical Officer of Health, instigated a football tournament to raise funds for the town's proposed new Victoria Hospital; it was a knockout competition between amateur clubs in the Burnley area, the final of which was played at Burnley's new home ground.[7] Burnley won the Dr Dean Trophy, a silver goblet, outright and their reserve team subsequently won the new Hospital Cup in 1884 and on multiple occasions in later years.[7][8]

By the end of 1883, the club had turned professional and signed many Scottish players, who were regarded as the best footballers.[9] As a result, Burnley refused to join the Football Association (FA) and its FA Cup because the association barred professional players.[10] In 1884, Burnley led a group of 35 clubs in the formation of the breakaway British Football Association (BFA) to challenge the supremacy of the FA.[10][11] The threat of secession led to the FA changing its rule in July 1885, allowing professionalism, which made the BFA redundant.[11] Burnley's main rivals at this point were neighbours Padiham and matches between the two teams attracted up to 12,000 fans.[9]

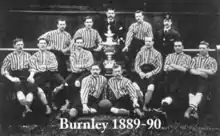

Burnley made their first appearance in the FA Cup in 1885–86; however, most professionals were prohibited entry due to FA rules that year,[lower-alpha 1] so Burnley fielded their reserve side and lost 11–0 to Darwen Old Wanderers.[13] In October 1886, Turf Moor became the first professional ground to be visited by a member of the Royal Family when Queen Victoria's grandson Prince Albert Victor attended a match between Burnley and Bolton Wanderers after he opened the town's new Victoria Hospital.[7][14] When the Football League was established for the 1888–89 season, Burnley were among the 12 founder members of the competition and one of the six Lancashire-based clubs.[15] In the second game, William Tait became the first player to score a league hat-trick when his three goals gave Burnley their inaugural win in the competition.[16][17] The club finished ninth in its first league season but only one place from bottom in 1889–90, following a run of 17 winless games at the start of the season.[18][19] That season, Burnley won their first Lancashire Cup after beating local rivals Blackburn Rovers 2–0 in the final.[18] Nicknames at this point were "Turfites", "Moorites" or "Royalites", as a result of their ground's name and the royal connection.[20]

Burnley were relegated to the Second Division for the first time in 1896–97.[19] The team won the division the next season, losing only two of 30 matches before gaining promotion through a four-team play-off series called test matches. The last game against First Division club Stoke was controversial; it finished 0–0 because both clubs needed only a draw to secure a promotion. The game was later named "The match without a shot at goal".[21] The Football League immediately withdrew the test match system in favour of automatic promotion and relegation; Burnley director and Football League management committee member Charles Sutcliffe had already proposed the discontinuation of test matches.[22] The Football League decided to expand the First Division from 16 clubs to 18 after a motion by Burnley, meaning the other two teams (Blackburn Rovers and Newcastle United) also went into the first tier.[23]

The team were relegated again in 1899–1900 and became the centre of a controversy when their goalkeeper Jack Hillman attempted to bribe opponents Nottingham Forest in the last match of the season, which resulted in Hillman's suspension for the whole of the following season.[24] It is possibly the earliest-recorded case of match fixing in football.[25] Burnley continued to play in the Second Division in the first decade of the 20th century; the side finished in last place in 1902–03 but were re-elected.[26] Alarming performances on the field and a considerable financial debt saw manager Ernest Mangnall leave the club for Manchester United in October 1903.[26] In 1907, 30-year-old Burnley supporter Harry Windle was invited onto the board to become a director and two years later, he was elected chairman. The club's finances improved under Windle's guidance.[26] The team reached the quarter-finals of the 1908–09 FA Cup but were eliminated by Manchester United in a replay. In the original match on the snow-covered pitch at Turf Moor, Burnley were leading 1–0 when the match was abandoned after 72 minutes.[27] In 1910, Mangnall's successor Spen Whittaker died after he fell off a train.[28] Windle appointed manager John Haworth,[29] who changed the club's colours from green to the claret and blue of First Division champions Aston Villa; Haworth and the Burnley directors believed the change might improve the club's fortunes.[30][lower-alpha 2] The team's form did improve; only a loss in the last game of the 1911–12 season denied the club promotion.[31]

Clarets' glory (1912–1946)

In the 1912–13 season, Burnley were promoted to the First Division and reached the FA Cup semi-finals but lost to Sunderland. The next season, the team consolidated their place in the top flight and won their first major honour, the FA Cup, after an 1–0 win against Liverpool in the final.[19] Bert Freeman, whose father travelled from Australia to see him play in the final,[32] scored the only goal as Burnley became the first club to beat five First Division clubs in one cup season.[33][34] This was the last final to be played at Crystal Palace. King George V became the first reigning monarch to attend an FA Cup Final and to present the cup to the winning captain, in this case to Tommy Boyle.[33][34]

The team finished fourth in 1914–15 before English football was suspended during wartime.[35] Upon resumption of full-time football in 1919–20, Burnley finished second to West Bromwich Albion and for the first time won the First Division championship in 1920–21.[19][36] Burnley lost the season's opening three matches before going on an unbeaten 30-match run, an English record for unbeaten league games in a single season that lasted until Arsenal went unbeaten through the whole of the 2003–04 FA Premier League season.[37][38] Burnley could not retain the title and finished third the following season.[39] In 1924, Haworth died of pneumonia, becoming the second Burnley manager to die while in the post.[40] In April 1926, Louis Page scored a club-record six goals in an away league match against Birmingham City (7–1).[41][42] Thereafter the club's league position steadily deteriorated, attaining only fifth place in 1926–27, a respite from a series of near-relegations that culminated in demotion to the Second Division in 1929–30.[19]

Burnley struggled in the Second Division, narrowly avoiding further relegation in 1931–32 by two points.[43][44] The years before the outbreak of the Second World War were characterised by uninspiring league finishes,[43] which were broken only by an FA Cup semi-final appearance in 1934–35,[45] and the arrival and swift departure of centre-forward Tommy Lawton.[46] The team participated in the football leagues that continued throughout the war until professional English football was fully restored in 1946.[47]

Progressive and golden era (1946–1976)

In the first season of post-war league football, Burnley took second place in the Second Division and gained promotion.[43] The team's defence was nicknamed the "Iron Curtain"; the team conceded only 29 goals in 42 league matches.[48] The season also saw a run to the 1947 FA Cup Final, beating Aston Villa, Coventry City, Luton Town, Middlesbrough and Liverpool before losing 1–0 after extra time to Charlton Athletic at Wembley.[49] The Burnley team made an immediate impact on the top division, finishing third in 1947–48 as they began to assemble a team that were capable of regularly aiming for honours.[50][51]

Former Burnley player Alan Brown was appointed manager in 1954 and Bob Lord chairman a year later;[51][52] Lord was later described as "the Khrushchev of Burnley" as a result of his authoritative attitude.[53][54] The club became one of the most progressive under their tenures.[53][55] Burnley was one of the first football clubs to set up a purpose-built training complex at Gawthorpe, which opened in July 1955.[52][56] Brown helped to dig out the ground and "volunteered" several of his players to assist.[57] The club also became renowned for its youth policy and scouting system, which yielded many young, talented footballers.[53] An acclaimed employed by Burnley during this period was Jack Hixon, who was mainly based in North East England and scouted many players, including Jimmy Robson, Brian O'Neil and Ralph Coates.[58] Brown introduced short corners and free kick routines.[59]

In the 1955–56 season, Burnley reached the fourth round of the FA Cup, where they were knocked out by Chelsea after four replays.[60] On his debut in 1956–57, 17-year-old Ian Lawson, a product of the club's youth academy,[61] scored a record four goals against Chesterfield in the FA Cup third round.[62] A tied club-record 9–0 victory over New Brighton in the next round followed despite missing a penalty. The following season, former Burnley player Harry Potts was appointed manager.[63] His squad mainly revolved around captain Jimmy Adamson and the team's playmaker Jimmy McIlroy.[64] Potts often employed the then-unfashionable 4–4–2 formation and implemented a Total Football playing style.[52][65]

The team endured a tense 1959–60 season, in which Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers were the other protagonists in the campaign for the league title. Burnley won their second First Division championship on the last day with a 2–1 victory at Manchester City with goals from Brian Pilkington and Trevor Meredith.[66] Although Burnley had been in contention all season, they had not led the table until the last match was played.[66] Potts used only 18 players during the whole season and John Connelly became their top scorer with 20 goals.[67] The squad cost £13,000 (equivalent to £300,000 in 2021)[lower-alpha 3] in transfer fees—£8,000 on McIlroy in 1950 and £5,000 on left-back Alex Elder in 1959. The other players were recruited from the side's youth academy.[53] With 80,000 inhabitants, the town of Burnley became the smallest to have an English first-tier champion.[53] After the season ended, the Burnley squad travelled to the United States to participate in the International Soccer League, the first modern international American football tournament.[68][69]

The following season, Burnley played in European competition for the first time in the 1960–61 European Cup, defeating former finalists Stade de Reims in the first round but being eliminated after losing to Hamburger SV in the quarter-finals.[70] Burnley finished fourth in the league and lost the FA Cup semi-final to Tottenham.[71] The team finished the 1961–62 First Division as runners-up to newcomers Ipswich Town after winning only two of the last thirteen matches, and had a run to the 1962 FA Cup Final but lost against Tottenham Hotspur. Robson scored the 100th FA Cup Final goal at Wembley but it was the only reply to Tottenham's three goals.[72][73] Adamson was named FWA Footballer of the Year, however, with McIlroy as runner-up.[74] Due to their success during this period, Burnley had several players with international caps, including England's Ray Pointer, Colin McDonald and Connelly, Northern Ireland's McIlroy and Scotland's Adam Blacklaw.[75]

Although Burnley were far from a two-man team, the controversial departure of McIlroy to Stoke City in 1963 and Adamson's retirement in 1964 coincided with a decline in the club's fortunes.[76] The impact of the abolition of the maximum wage in 1961, which meant clubs from small towns like Burnley could no longer compete financially with sides from bigger towns and cities, was more damaging.[52][77] The club, however, retained its place in the First Division throughout the decade, finishing third in 1965–66 with Willie Irvine as the league's top goal scorer, and reaching the League Cup semi-final in 1968–69.[19][78] Burnley also reached the quarter-finals of the 1966–67 Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, in which they were knocked out by West German side Eintracht Frankfurt.[79]

After 12 years in the post, Potts was replaced by Adamson as manager in 1970.[80] Adamson hailed his squad as the "Team of the Seventies" but was unable to halt the decline and the club was relegated in 1970–71.[80] It ended an unbroken top-flight spell of 24 consecutive seasons during which Burnley had often been in the top half of the league table.[19] Burnley won the Second Division title in 1972–73, losing only four times in 42 matches.[81] As a result, the team were invited to play in the 1973 FA Charity Shield, which they won against Manchester City, the reigning holders of the shield.[82] In the First Division, led by playmaker Martin Dobson and Leighton James, the side finished sixth in 1973–74 and reached the FA Cup semi-finals, in which they lost to Newcastle United.[19][83] The following season, the team experienced a shock defeat in the FA Cup against Wimbledon, then in the Southern League, who defeated Burnley 1–0 at Turf Moor.[84] Adamson left Burnley in January 1976 and the team were relegated from the First Division later that year.[85] During this period, a drop in home attendances combined with an enlarged debt forced Burnley to sell star players such as Dobson and James, which caused a rapid decline in the club's fortunes.[86]

Decline and near oblivion (1976–1987)

Three nondescript seasons in the Second Division followed before relegation to the Third Division in 1979–80 for the first time.[19] In 42 league games, Burnley won none of the first 16 or the last 16 games.[87] In September 1981, after the club was in the Third Division relegation zone and close to bankruptcy, Lord decided to retire.[86] The team then climbed out of the relegation zone and had only three more defeats after October as they were promoted as champions under the management of former Burnley player Brian Miller.[88] They were relegated the following year, a season in which the team reached the FA Cup quarter-finals and the League Cup semi-final, defeating Tottenham and Liverpool in the latter. Burnley won 1–0 against Liverpool in the League Cup semi-final second leg but they were eliminated after losing the first leg 3–0.[19]

Managerial changes continued; in early 1983, Miller was replaced with Frank Casper, who was succeeded by John Bond before the 1983–84 season.[89] Bond was the first manager since Frank Hill (1948–1954) without a previous playing career at the club; fans criticised Bond for signing expensive players, increasing Burnley's debt, and for selling young talents Lee Dixon, Brian Laws and Trevor Steven.[90] The following season, Bond was replaced with John Benson, who was in charge when Burnley were relegated to the Fourth Division for the first time at the end of the 1984–85 season.[89] It was the fifth relegation in the past 15 seasons; the club finished 21st in each of those five seasons.[19]

For the 1985–86 season, Burnley were managed briefly by Martin Buchan and then Tommy Cavanagh before Miller returned for the 1986–87 season,[89] the last match of which is known as "the Orient Game".[91] For the 1986–87 season, the Football League introduced automatic relegation and promotion between the Fourth Division and the Football Conference,[92] the top tier of non-league football in England.[91] Burnley had a new local rival team in Colne Dynamoes, who were rapidly progressing through the English non-league system.[93] Colne's chairman-manager Graham White made a proposal for a groundshare of Turf Moor and attempted to buy the club in early 1989; the Burnley board rejected these offers.[94] In 1987, the Burnley board reportedly attempted to purchase almost-bankrupt Welsh club Cardiff City and relocate it to Turf Moor if Burnley were relegated; this would have been the Football League's first franchise operation.[95]

During the 1986–87 season, Burnley had only 12 wins in 46 league games and suffered a 3–0 FA Cup first round defeat at non-league Telford United.[19][96] Burnley went into the season's last match in bottom place and needing a win against Orient, needing Lincoln City to lose and for Torquay United to lose or draw.[91] A 2–1 win before a crowd of over 15,000[lower-alpha 4] with goals from Neil Grewcock and Ian Britton kept Burnley in the Fourth Division as Torquay drew and Lincoln lost.[91]

Recovery (1987–2009)

In 1988, Burnley were back at Wembley to play Wolverhampton Wanderers in the final of the 1988 Associate Members' Cup Final, which they lost 2–0. The match was attended by more than 80,000 people, a record for a game between two teams from the fourth tier.[98] In 1990–91, Burnley qualified for the Fourth Division play-offs under manager Casper but were eliminated in the semi-final by Torquay United.[99] Burnley became champions the following season under their new manager Jimmy Mullen in the last-ever season of the Fourth Division before the league reorganisation.[92][100] Mullen had succeeded Casper in October 1991 and won his first nine league matches as manager.[100] By winning the fourth tier, Burnley became only the second club to win all four professional divisions of English football after Wolverhampton Wanderers.[101][102]

In 1993–94, the team won the Second Division play-offs and gained promotion to the second tier. They won 3–1 on aggregate against Plymouth Argyle in the semi-final and faced Stockport County in the final. In front of approximately 35,000 Burnley supporters and a total attendance of 44,806, Burnley won the game 2–1 as two Stockport players were sent off.[103][104] Relegation followed after one season and in 1997–98, only a last-day 2–1 victory over Plymouth prevented relegation back into the fourth tier.[105][106] Chris Waddle was player-manager that season with his assistant Glenn Roeder;[107] their departures and the appointment of Stan Ternent that summer saw the club make further progress.[108] Burnley finished second in 1999–2000 and gained promotion to the second tier; the striker and lifelong Burnley fan Andy Payton was the division's top goal scorer.[109][110]

Burnley immediately became serious contenders for a promotion play-off place during the 2000–01 and 2001–02 seasons.[19] In the latter season, the team missed the last play-off place by one goal.[111] In early 2002, financial problems caused by the collapse of ITV Digital brought the club close to administration again.[112] By 2002–03, the club's on-field form had also declined despite reaching the FA Cup quarter-finals.[19] Ternent's six years as manager ended in June 2004 after the club narrowly avoided relegation with a squad composed of many loaned players and some regular players who were not entirely fit.[113][114] Steve Cotterill was then appointed as manager.[115] His first year in charge produced two notable cup runs; the team beat Liverpool and Aston Villa in the third rounds of the FA Cup and the League Cup, respectively.[116] In 2006, Turf Moor and Gawthorpe were sold to Longside Properties for £3 million (equivalent to £4,370,000 in 2021)[lower-alpha 3] to resolve the club's financial problems. Chairman Barry Kilby owned 51 per cent of the company's shares.[117] In the 2006–07 campaign, between December and March, Burnley went 19 consecutive games without a win.[118] The sequence of draws and losses ended in April, when Burnley beat Plymouth 4–0 at home and a short run of good form saw them finish comfortably above the relegation zone, ensuring they remained in the Championship.[119]

The following season, a run of poor results led to Cotterill's departure in November 2007.[120] His replacement was St Johnstone manager Owen Coyle.[121] The 2008–09 season, Coyle's first full season in charge, ended with Burnley's highest league finish since 1976; fifth in the Championship.[19][122] Burnley qualified for the Championship play-offs and defeated Reading 3–0 on aggregate in the semi-final.[123] Sheffield United were defeated in the Championship play-off final, which meant promotion to the top flight after 33 years. Wade Elliott scored the only goal.[124] Burnley also reached the League Cup semi-final for the first time in over 25 years after beating local clubs Bury and Oldham Athletic, and London-based clubs Fulham, Chelsea and Arsenal.[125][126] In the semi-finals, Burnley played Tottenham but lost the first leg 4–1.[127] After leading 3–0 at home after 90 minutes,[lower-alpha 5] the side were eliminated after Tottenham scored two goals in the last two minutes of extra time.[129]

Premier League promotions, relegations and back in Europe (2009–present)

After the team's promotion, Burnley became the smallest town to host a Premier League club.[130][131] The team started the 2009–10 season well and became the first newly promoted side in the competition to win their first four home games, including a 1–0 win over defending champions Manchester United.[132][133] Manager Coyle left the club in January 2010 to manage local rivals Bolton Wanderers, whom he said were "5 or 10 years ahead" of Burnley.[134] Coyle was replaced with Brian Laws, under whom Burnley's form deteriorated and the team were relegated after a single season in the Premier League.[135] Laws was dismissed in December 2010 and replaced with Bournemouth manager Eddie Howe,[136] who in his first season guided the team to an eighth-place finish in the Championship, narrowly missing out on a play-off place.[137] In October 2012, Howe left Burnley to rejoin Bournemouth for personal reasons.[138] He was replaced the same month with Watford manager Sean Dyche.[139]

Before the start of the 2013–14 season, Turf Moor and Gawthorpe returned to club ownership after a seven-year period.[140] Burnley were tipped as relegation candidates; Dyche had to work with a tight budget and a small squad, and Burnley's top goal scorer Charlie Austin had moved to Championship rivals Queens Park Rangers.[141] In Dyche's first full season in charge, however, Burnley finished the season second and were automatically promoted back to the Premier League.[142] The new strike partnership of Danny Ings and Sam Vokes had 41 league goals between them.[143] Dyche used only 23 players during the season, which was the joint-lowest in the division, and had paid only one transfer fee—£400,000 for striker Ashley Barnes.[144] The club finished the following season 19th out of 20 clubs and were again relegated to the Championship.[145] In 2015–16, Burnley won the Championship title when they equalled their 2013–14 club record of 93 points and ended the season with a run of 23 undefeated league games.[146] The new signing Andre Gray scored 23 goals for Burnley, becoming the league's top goal scorer.[147]

The side finished the 2016–17 season in 16th place, six points above the relegation zone, and were thus ensured to play consecutive seasons in the top flight for the first time in the Premier League era.[148] In that season's FA Cup competition, Burnley were eliminated in the fifth round at home by National League club Lincoln City, who won the game 1–0; this was Burnley's second FA Cup home defeat against a non-league club while in the top flight since 1975.[149] In 2017, the club's new Barnfield Training Centre, which replaced the 60-year-old Gawthorpe, was completed.[150] Dyche was involved in the design and had willingly tailored his transfer spending as he and the board focused on the club's infrastructure and future.[150][151] Burnley finished the 2017–18 season in seventh place, winning more points away than at home; it was their highest league finish since 1973–74.[152] Burnley qualified for the 2018–19 UEFA Europa League, their first competitive European campaign in 51 years,[152] but were eliminated in the play-off round against Greek side Olympiacos after defeating Scottish club Aberdeen and Turkish side İstanbul Başakşehir in the previous qualifying rounds.[153]

The 2019–20 season was interrupted for three months because of the COVID-19 pandemic before being completed behind closed doors; in that period, Dyche's assistant manager Ian Woan tested positive for the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus.[154][155] Burnley concluded the campaign in 10th place, five points away from the European places.[156][157] In December 2020, American investment company ALK Capital acquired an 84% stake in Burnley for £200 million. It was the first time the club was run by persons other than local businessmen and Burnley supporters.[158]

Notes

- Professionals could only play in the FA Cup and County FA competitions if they had been born or had resided within six miles (9.7 km) of their club's ground for a minimum of two years.[12]

- In the early years, Burnley used various kit designs and colours. From 1900 until 1910, the team wore an all-green jersey.[3]

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- The average home league attendance before the match was 2,800.[97]

- In the League Cup, the away goals rule only comes into play after extra time has been played.[128]

Sources

References

- Simpson (2007), p. 12

- Simpson (2007), pp. 18–19

- Simpson (2007), p. 586

- Simpson (2007), p. 574

- "The Turf Moor Story". Burnley F.C. 3 July 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Smith, Rory (26 May 2009). "10 things you probably didn't know about Burnley". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Simpson, Ray (5 December 2017). "The Story Of The Dr Dean Trophy". Burnley F.C. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Simpson (2007), p. 20

- Simpson (2007), pp. 20–24

- Simpson (2007), p. 22

- Butler, Bryon (1991). The Official History of The Football Association. Queen Anne Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-356-19145-1.

- Simpson (2007), p. 24

- Smith (2014), p. 3

- Fiszman, Marc; Peters, Mark (2005). Kick Off Championship 2005–06. Sidan Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781903073322.

- Simpson (2007), p. 28

- Bradford, Tim (2006). When Saturday Comes: The Half Decent Football Book. Penguin Adult. p. 134. ISBN 978-0141015569.

- Simpson (2007), p. 30

- Simpson (2007), pp. 35–36

- Rundle, Richard. "Burnley". Football Club History Database. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Geldard, Suzanne (2 June 2007). "No 10: The meeting that gave birth to Clarets". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 67–68

- Inglis, Simon (1988). League Football and the Men Who Made It. Willow Books. p. 107. ISBN 0-00-218242-4.

- Burnton, Simon (28 November 2018). "The forgotten story of ... 'evil' Football League test matches". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 75–76

- Dart, James; Bandini, Paolo (9 August 2006). "The earliest recorded case of match-fixing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Smith (2014), pp. 3–5

- Smith (2014), pp. 20–27

- Smith (2014), p. 34

- Smith (2014), pp. 328–329

- "On This Day: 13 July". Burnley F.C. 13 July 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 123–124

- Smith (2014), p. 260

- Smith (2014), p. 343

- "Clarets on top in first royal final". Lancashire Telegraph. 5 January 2005. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 134–135

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (31 October 2013). "England 1919–20". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Simpson (2007), p. 152

- Smith (2014), p. 309

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (31 October 2013). "England 1921–22". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Smith (2014), pp. 329–331

- "Clarets: Barnes stormer". Lancashire Telegraph. 7 October 1996. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Birmingham City v Burnley, 10 April 1926". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Archived from the original on 29 December 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Simpson (2007), p. 529

- Edwards, Gareth; Felton, Paul (21 September 2000). "England 1931–32". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Reyes Padilla, Macario (8 February 2001). "England FA Challenge Cup 1934–1935". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Ponting, Ivan (7 November 1996). "Obituary: Tommy Lawton". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 226–240

- Thomas, Dave (2014). Who Says Football Doesn't Do Fairytales?: How Burnley Defied the Odds to Join the Elite. Pitch Publishing Ltd. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1909626690.

- Heneghan, Michael (12 December 2002). "England FA Challenge Cup 1946–1947". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Felton, Paul. "Season 1947–48". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Quelch (2015), pp. 207–208

- McParlan, Paul (27 February 2018). "Burnley, Total Football and the pioneering title win of 1959/60". These Football Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Quelch (2015), pp. 199–206

- Bagchi, Rob (27 May 2009). "Burnley are back – thankfully without caricature chairman Bob Lord". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- York, Gary (24 May 2007). "John Connelly life story: Part 1". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Marshall, Tyrone (24 March 2017). "Training ground move a sign of our ambition, says Burnley captain Tom Heaton as Clarets move into their new home". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Ponting, Ivan (12 March 1996). "Alan Brown". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Scout Hixon back on the Turf payroll". Lancashire Telegraph. 5 July 2000. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Quelch (2015), p. 11

- Bishop, Paul (15 August 2014). "Instant replay: FA Cup marathon for Chelsea and Burnley". Get West London. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Simpson (2007), p. 497

- Turner, Georgina (24 September 2013). "Was Jesse Lingard's debut for Birmingham the most prolific ever?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 281–284

- Glanville, Brian (20 August 2018). "Jimmy McIlroy obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Ponting, Ivan (22 January 1996). "Obituary: Harry Potts". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Marshall, Tyrone (20 June 2016). "'We weren't jumping around, we'd only won the league' – Burnley legend on the day the Clarets were crowned Kings of England". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2015), p. 265

- Posnanski, Joe (14 October 2014). "David and Goliath and Burnley". NBC SportsWorld. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Litterer, David A. (15 December 1999). "USA – International Soccer League II". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 296–297

- "'Back then, we were the teams to watch' – Cliff Jones on our rivalry with Burnley in the early 1960s". Tottenham Hotspur F.C. 29 March 2017. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Veevers, Nicholas (5 January 2015). "Robson recalls historic Cup Final goal and Spurs rivalry". The Football Association. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 301–303

- Chadwick, Wallace (20 August 2018). "Jimmy McIlroy: A Turf Moor Legend". Burnley F.C. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 532–538

- Simpson (2007), pp. 304–311

- Shaw, Phil (18 January 2016). "EFL Official Website Fifty-five years to the day: £20 maximum wage cap abolished by Football League clubs". English Football League. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Ross, James M. (20 June 2019). "English League Leading Goalscorers". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Burnley v Eintracht Frankfurt, 18 April 1967". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 546–549

- Felton, Paul. "Season 1972–73". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Clayton, David (2 August 2018). "City and the FA Community Shield: Complete record". Manchester City F.C. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Struthers, Greg (2 May 2004). "Caught in Time: Burnley return to the First Division, 1973 74". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "The biggest FA Cup shocks in the history of the game". The Independent. 18 February 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 357–358

- Quelch (2017), pp. 17–20

- "Burnley match record: 1980". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 380–383

- Simpson (2007), pp. 550–555

- Quelch (2017), pp. 24–39

- Davies, Tom (26 April 2018). "Golden Goal: Neil Grewcock saves Burnley v Orient (1987)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "History Of The Football League". The Football League. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), p. 413

- Whalley, Mike (May 2008). "The Colne Dynamoes debacle". When Saturday Comes. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), p. 62

- "History". AFC Telford United. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Quelch (2017), p. 63

- Donlan, Matt (18 December 2009). "Sherpa final a turning point in Burnley's history". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 104–106

- Simpson (2007), pp. 420–423

- Tyler, Martin (9 May 2017). "Martin Tyler's stats: Most own goals, fewest different scorers in a season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Club Honours & Records". Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Metcalf, Rupert (23 October 2011). "Football Play-Offs: County fall short as Burnley go up: Parkinson makes the difference". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 428, 509

- Heneghan, Michael; Monger, Rob; Mulrine, Stephen; Ross, James M. (4 November 2011). "England 1994/95". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- James, Alex (3 May 2020). "A turning point in Burnley's history – story of dramatic 1998 last day drama by the man who saved the Clarets". Lancs Live. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Quelch (2017), p. 160

- Walker, Michael (29 December 2001). "The Saturday Interview: Ternent close to matching the great Clarets". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Boden, Chris (6 May 2020). "Twenty years on – Golden Boot winner Andy Payton on promotion, a big "turning point" in Burnley's modern history". Burnley Express. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Excerpt from former Burnley striker Andy Payton's upcoming book". The Clitheroe Advertiser and Times. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Quelch (2017), p. 198

- Quelch (2017), pp. 197–202

- "Clarets manager booted out". Lancashire Telegraph. 4 May 2004. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 204–213

- "Cotterill lands Burnley job". The Guardian. 3 June 2004. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Simpson (2007), p. 474

- Quelch (2017), p. 227

- "Burnley match record: 2007". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 481–483

- "Burnley manager Cotterill departs". BBC Sport. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Burnley announce appointment of Owen Coyle as their new manager". The Guardian. 22 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Lomax, Andrew (3 May 2009). "Owen Coyle insists Burnley are hitting form at the right time". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Fletcher, Paul (12 May 2009). "Reading 0–2 Burnley (agg 0–3)". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Fletcher, Paul (25 May 2009). "Burnley 1–0 Sheff Utd". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Cross, Jeremy (3 December 2008). "Carling Cup: Arsene Wenger fumes as Burnley turf out Arsenal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- King, Ian (6 March 2009). "England League Cup 2008/09". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- McNulty, Phil (6 January 2009). "Tottenham 4–1 Burnley". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Sheen, Tom (28 January 2015). "Do away goals count in the Capital One Cup semi-final?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Hughes, Ian (21 January 2009). "Burnley 3–2 Tottenham (agg 4–6)". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Smith, Rory (9 August 2017). "When the Premier League Puts Your Town on the Map". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Bournemouth: The minnows who made the Premier League". BBC Sport. 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Coyle Hails Best Win Yet". Burnley F.C. 6 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- McNulty, Phil (19 August 2009). "Burnley 1–0 Man Utd". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Taylor, Daniel (11 January 2010). "'Everything I want is here,' says Owen Coyle as he moves in at Bolton". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Lovejoy, Joe (25 April 2010). "Liverpool seal Burnley's relegation on back of Steven Gerrard double". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "Howe confirmed as Burnley manager". BBC Sport. 16 January 2011. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "2010/2011 Season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Eddie Howe: Bournemouth agree deal with Burnley for manager". BBC Sport. 12 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Burnley: Sean Dyche named as new manager at Turf Moor". BBC Sport. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Turf Moor buy-back complete". Eurosport. 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 318–319

- "2013/2014 Season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Quelch (2017), p. 332

- Cryer, Andy (21 April 2014). "Burnley 2–0 Wigan Athletic". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "2014/2015 Season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Marshall, Tyrone (7 May 2016). "'It means a lot' – Sean Dyche hails Burnley's title triumph after Charlton victory". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Marshall, Tyrone (21 June 2016). "'Padiham Predator' backs Andre Gray to be Premier League success for Clarets". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Emons, Michael (21 May 2017). "Burnley 1–2 West Ham United". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Lofthouse, Amy (18 February 2017). "Burnley 0–1 Lincoln City". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Marshall, Tyrone (24 March 2017). "Training ground move a sign of our ambition, says Burnley captain Tom Heaton as Clarets move into their new home". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Whalley, Mike (5 August 2017). "Sean Dyche has new grounds for optimism as Burnley spend £10.5m on training facility". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Sutcliffe, Steve (13 May 2018). "Burnley 1–2 Bournemouth". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Johnston, Neil (30 August 2018). "Burnley 1–1 Olympiakos (2–4 on agg)". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "The Premier League returns — all you need to know". BBC Sport. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Burnley assistant manager Ian Woan tests positive for coronavirus". BBC Sport. 19 May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "2019/2020 Season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Begley, Emlyn (22 July 2020). "Premier League: Who can qualify for Champions League and Europa League?". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Geldard, Suzanne (31 December 2020). "Burnley's takeover by American company ALK Capital complete". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

Bibliography

- Quelch, Tim (2015). Never Had It So Good: Burnley's Incredible 1959/60 League Title Triumph. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1909626546.

- Quelch, Tim (2017). From Orient to the Emirates: The Plucky Rise of Burnley FC. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1785313127.

- Simpson, Ray (2007). The Clarets Chronicles: The Definitive History of Burnley Football Club 1882-2007. Burnley F.C. ISBN 978-0955746802.

- Smith, Mike (2014). The Road to Glory: Burnley's FA Cup Triumph in 1914. Grosvenor House Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1781486900.

External links

- Club history at the Burnley F.C. website

- Early club history at Clarets Mad

- The Longside – Your Online Clarets Encyclopedia (archived)