History of Alexandria

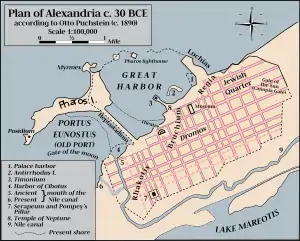

The history of Alexandria dates back to the city's founding, by Alexander the Great, in 331 BC.[1] Yet, before that, there were some big port cities just east of Alexandria, at the western edge of what is now Abu Qir Bay. The Canopic (westernmost) branch of the Nile Delta still existed at that time, and was widely used for shipping.

After its foundation, Alexandria became the seat of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, and quickly grew to be one of the greatest cities of the Hellenistic world. Only Rome, which gained control of Egypt in 30 BC, eclipsed Alexandria in size and wealth.

The city fell to the Arabs in AD 641, and a new capital of Egypt, Fustat, was founded on the Nile. After Alexandria's status as the country's capital ended, it fell into a long decline, which by the late Ottoman period, had seen it reduced to little more than a small fishing village. The French army under Napoleon captured the city in 1798 and the British soon captured it from the French, retaining Alexandria within their sphere of influence for 150 years. The city grew in the early 19th century under the industrialization program of Mohammad Ali, the viceroy of Egypt.

The current city is the Republic of Egypt's leading port, a commercial, tourism and transportation center, and the heart of a major industrial area where refined petroleum, asphalt, cotton textiles, processed food, paper, plastics and styrofoam are produced.

Early settlements in the area

Just east of Alexandria in ancient times (where now is Abu Qir Bay) there was marshland and several islands. As early as the 7th century BC, there existed important port cities of Canopus and Heracleion. The latter was recently rediscovered under water. Part of Canopus is still on the shore above water, and had been studied by archaeologists the longest. There was also the town of Menouthis. The Nile Delta had long been politically significant as the point of entry for anyone wishing to trade with Egypt.[2]

An Egyptian city or town, Rhakotis, existed on the shore where Alexandria is now. Behind it were five villages scattered along the strip between Lake Mareotis and the sea, according to the Romance of Alexander.

Foundation

Alexandria was founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BC (the exact date is disputed) as Ἀλεξάνδρεια (Aleksándreia). Alexander's chief architect for the project was Dinocrates. Ancient accounts are extremely numerous and varied, and much influenced by subsequent developments. One of the more sober descriptions, given by the historian Arrian, tells how Alexander undertook to lay out the city's general plan, but lacking chalk or other means, resorted to sketching it out with grain. A number of more fanciful foundation myths are found in the Alexander Romance and were picked up by medieval historians.

A few months after the foundation, Alexander left Egypt for the East and never returned to his city. After Alexander departed, his viceroy, Cleomenes, continued the expansion of the city.

In a struggle with the other successors of Alexander, his general, Ptolemy (later Ptolemy I of Egypt) succeeded in bringing Alexander's body to Alexandria. Alexander's tomb became a famous tourist destination for ancient travelers (including Julius Caesar). With the symbols of the tomb and the Lighthouse, the Ptolemies promoted the legend of Alexandria as an element of their legitimacy to rule.[3]

Alexandria was intended to supersede Naucratis as a Hellenistic center in Egypt, and to be the link between Greece and the rich Nile Valley. If such a city was to be on the Egyptian coast, there was only one possible site, behind the screen of the Pharos island and removed from the silt thrown out by the Nile, just west of the westernmost "Canopic" mouth of the river. At the same time, the city could enjoy a fresh water supply by means of a canal from the Nile.[4] The site also offered unique protection against invading armies: the vast Libyan Desert to the west and the Nile Delta to the east.

Though Cleomenoes was mainly in charge of seeing to Alexandria's continuous development, the Heptastadion (causeway to Pharos Island) and the main-land quarters seem to have been mainly Ptolemaic work. Demographic details of how Alexandria rose quickly to its great size remain unknown.[5]

Ptolemaic era

Inheriting the trade of ruined Tyre and becoming the center of the new commerce between Europe and the Arabian and Indian East, the city grew in less than a generation to be larger than Carthage. In a century, Alexandria had become the largest city in the world,[6] and for some centuries more, was second only to Rome. It became the main Greek city of Egypt, with an extraordinary mix of Greeks from many cities and backgrounds.[7] Nominally a free Hellenistic city, Alexandria retained its senate of Roman times and the judicial functions of that body were restored by Septimius Severus after temporary abolition by Augustus.

Construction

Monumental buildings were erected in Alexandria through the third century BC. The Heptastadion connected Pharos with the city and the Lighthouse of Alexandria followed soon after, as did the Serapeum, all under Ptolemy I. The Museion was built under Ptolemy II; the Serapeum expanded by Ptolemy III Euergetes; and mausolea for Alexander and the Ptolemies built under Ptolemy IV.[8]

Library of Alexandria

The Ptolemies fostered the development of the Library of Alexandria and associated Musaeum into a renowned center for Hellenistic learning.

Luminaries associated with the Musaeum included the geometry and number-theorist Euclid; the astronomer Hipparchus; and Eratosthenes, known for calculating the Earth's circumference and for his algorithm for finding prime numbers, who became head librarian.

Strabo lists Alexandria, with Tarsus and Athens, among the learned cities of the world, observing also that Alexandria both admits foreign scholars and sends its natives abroad for further education.[9]

Ethnic divisions

The early Ptolemies were careful to maintain the distinction of its population's three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian. (At first, Egyptians were probably the plurality of residents, while the Jewish community remained small. Slavery, a normal institution in Greece, was likely present but details about its extent and about the identity of slaves are unknown.)[10] Alexandrian Greeks placed an emphasis on Hellenistic culture, in part to exclude and subjugate non-Greeks.[11]

The law in Alexandria was based on Greek—especially Attic—law.[12] There were two institutions in Alexandria devoted to the preservation and study of Greek culture, which helped to exclude non-Greeks. In literature, non-Greek texts entered the library only once they had been translated into Greek. Notably, there were few references to Egypt or native Egyptians in Alexandrian poetry; one of the few references to native Egyptians presents them as "muggers."[11] There were ostentatious religious processions in the streets that displayed the wealth and power of the Ptolemies, but also celebrated and affirmed Greekness. These processions were used to shout Greek superiority over any non-Greeks that were watching, thereby widening the divide between cultures.[13]

From this division arose much of the later turbulence, which began to manifest itself under the rule of Ptolemy Philopater (221–204 BC). The reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon from 144–116 BC was marked by purges and civil warfare (including the expulsion of intellectuals such as Apollodorus of Athens), as well as intrigues associated with the king's wives and sons.

Alexandria was also home to the largest Jewish community in the ancient world. The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Torah and other writings), was produced there. Jews occupied two of the city's five quarters and worshipped at synagogues.

Roman era

Roman annexation

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The city passed formally under Roman jurisdiction in 80 BC, according to the will of Ptolemy Alexander but only after it had been under Roman influence for more than a hundred years. Julius Caesar dallied with Cleopatra in Alexandria in 47 BC and was besieged in the city by Cleopatra's brother and rival. His example was followed by Mark Antony, for whose favor the city paid dearly to Octavian. Following Antony's defeat at the Battle of Actium, Octavian took Egypt as personal property of the emperor, appointing a prefect who reported personally to him rather than to the Roman Senate. While in Alexandria, Octavian took time to visit Alexander's tomb and inspected the late king's remains. On being offered a viewing into the tombs of the pharaohs, he refused, saying, "I came to see a king, not a collection of corpses."[14]

From the time of annexation and onwards, Alexandria seemed to have regained its old prosperity, commanding, as it did, an important granary of Rome. This was one of the chief reasons that induced Octavian to place it directly under imperial power.

Jewish–Greek ethnic tensions in the era of Roman administration led to riots in AD 38 and again in 66. Buildings were burned during the Kitos War (Tumultus Iudaicus) of AD 115, giving Hadrian and his architect, Decriannus, an opportunity to rebuild.

In 215 AD the emperor Caracalla visited the city and, because of some insulting satires that the inhabitants had directed at him, abruptly commanded his troops to put to death all youths capable of bearing arms. This brutal order seems to have been carried out even beyond the letter, for a general massacre ensued. According to historian Cassius Dio, over 20,000 people were killed.

In the 3rd century AD, Alexander's tomb was closed to the public, and now its location has been forgotten.

Late Roman and Byzantine period

Even as its main historical importance had sprung from pagan learning, Alexandria now acquired new importance as a center of Christian theology and church government. There, Arianism came to prominence, and there also Athanasius opposed Arianism and the pagan reaction against Christianity, experiencing success against both and continuing the Patriarch of Alexandria's major influence on Christianity into the next two centuries.

%252C_1866.jpg.webp)

Persecution of Christians under Diocletian (beginning in AD 284) marks the beginning of the Era of Martyrs in the Coptic calendar.[15]

As native influences began to reassert themselves in the Nile valley, Alexandria gradually became an alien city, more and more detached from Egypt and losing much of its commerce as the peace of the empire broke up during the 3rd century, followed by a fast decline in population and splendor.

In 365, a tsunami caused by an earthquake in Crete hit Alexandria.[16][17]

In the late 4th century, persecution of pagans by Christians had reached new levels of intensity. Temples and statues were destroyed throughout the Roman empire: pagan rituals became forbidden under punishment of death, and libraries were closed. In 391, Emperor Theodosius I ordered the destruction of all pagan temples, and the Patriarch Theophilus complied with his request. The Serapeum of the Great Library was destroyed, possibly effecting the final destruction of the Library of Alexandria.[18][19] The neoplatonist philosopher Hypatia was publicly murdered by a Christian mob.

The Brucheum and Jewish quarters were desolate in the 5th century, and the central monuments, the Soma and Museum, fell into ruin. On the mainland, life seemed to have centered in the vicinity of the Serapeum and Caesareum, both which became Christian churches. The Pharos and Heptastadium quarters, however, remained populous and were left intact.

Recent archaeology at Kom El Deka (heap of rubble or ballast) has found the Roman quarter of Alexandria beneath a layer of graves from the Muslim era. The remains found at this site, which are dated circa the fourth to seventh centuries AD, include workshops, storefronts, houses, a theater, a public bath, and lecture halls, as well as Coptic frescoes. The baths and theater were built in the fourth century and the smaller buildings constructed around them, suggesting a sort of urban renewal occurring in the wake of Diocletian.[20]

Arab rule

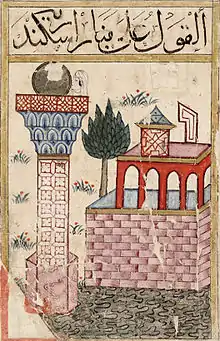

In 616, the city was taken by Khosrau II, King of Persia. Although the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius recovered it a few years later, in 641 the Arabs, under the general Amr ibn al-As during the Muslim conquest of Egypt, captured it decisively after a siege that lasted fourteen months. The city received no aid from Constantinople during that time; Heraclius was dead and the new Emperor Constans II was barely twelve years old. In 645 a Byzantine fleet recaptured the city, but it fell for good the following year. Thus ended a period of 975 years of the Greco-Roman control over the city. Nearly two centuries later, between the years 814 and 827, Alexandria came under the control of pirates of Andalusia (Spain today), later to return to Arab hands.[21] In the year 828, the alleged body of Mark the Evangelist was stolen by Venetian merchants, which led to the Basilica of Saint Mark. Years later, the city suffered many earthquakes during the years 956, 1303 and then in 1323. After a long decline, Alexandria emerged as major metropolis at the time of the Crusades and lived a flourishing period due to trade with agreements with the Aragonese, Genoese and Venetians who distributed the products arrived from the East through the Red Sea. It formed an emirate of the Ayyubid Empire, where Saladin's elder brother Turan Shah was granted a sinecure to keep him from the front lines of the crusades. In the year 1365, Alexandria was brutally sacked after being taken by the armies of the Crusaders, led by King Peter of Cyprus. The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Venice has eliminated the jurisdiction and its Alexandrian warehouse became the center of the distribution of spices to the Portuguese Cape route to open in 1498, which marks the commercial decline, worsened by the Turkish invasion.

There has been a persistent belief that the Library of Alexandria and its contents were destroyed in 642 during the Arab invasion.[19][18]

The Lighthouse was destroyed by earthquakes in the 14th century,[22] and by 1700 the city was just a small town amidst the ruins.

Though smaller, the city remained a significant port for Mediterranean trade well through the medieval period, under the Mamluk sultanate, playing a part in the trade network of Italian city-states.[23] However, it declined still further under the Ottoman Empire, losing its water supply from the Nile, and its commercial importance, as Rosetta (Rashid) became more useful as a port.[24]

Modern history

Napoleonic invasion

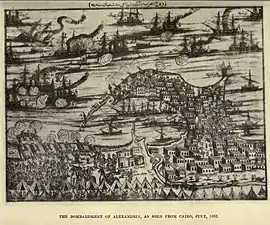

Alexandria figured prominently in the military operations of Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in 1798. French troops stormed the city on July 2, 1798 and it remained in their hands until the British victory at the Battle of Alexandria on March 21, 1801, following which the British besieged the city which fell to them on 2 September 1801.

Two French savants assessing the population of Alexandria in 1798 estimated 8,000 and 15,000.[25]

Mohammed Ali

Mohammed Ali, the Ottoman Governor of Egypt, began rebuilding the city around 1810, and by 1850, Alexandria had returned to something akin to its former glory.

British occupation

In July 1882 the city was the site of the first battle of the Anglo-Egyptian War, when it was bombarded and occupied by British naval forces. Large sections of the city were damaged in the battle, or destroyed in subsequent fires.[26]

Republic of Egypt

Relations with the United Kingdom grew strained in the 1950s, with violence periodically erupting between local police and the British army, in Alexandria as well as in Cairo. These clashes culminated in the Egyptian coup of 1952, during which the army occupied Alexandria and drove King Farouk from his residence at Montaza Palace.[27]

In July 1954, the city was a target of an Israeli bombing campaign that later became known as the Lavon Affair. Only a few months later, Alexandria's Manshia Square was the site of the famous, failed assassination attempt on the life of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Mayors of Alexandria (since the implementation of the local-government act of 1960):[28]

- Siddiq Abdul-Latif (October 1960 - November 1961)

- Mohammed Hamdi Ashour (November 1961 - October 1968)

- Ahmad Kamil (October 1968 - November 1970)

- Mamdouh Salim (November 1970 - May 1971)

- Ahmad Fouad Mohyee El-Deen (May 1971 - September 1972)

- Abdel-Meneem Wahbi (September 1972 - May 1974)

- Abdel-Tawwab Ahmad Hadeeb (May 1974 - November 1978)

- Mohammed Fouad Helmi (November 1978 - May 1980)

- Naeem Abu-Talib (May 1980 - August 1981)

- Mohammed Saeed El-Mahi (August 1981 - May 1982)

- Mohammed Fawzi Moaaz (May 1982 - June 1986)

- Ismail El-Gawsaqi (July 1986 - July 1997)

- Abdel-Salam El-Mahgoub (1997–2006)

- Adel Labib (August 2006 - )

Arts

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighborhoods, turn gray in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

From Constantine P. Cavafy, "The City" (1910), translated by Edmund Keeley

Alexandria was the home of the ethnically Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy. E. M. Forster, who worked in Alexandria for the International Red Cross during World War I, wrote two books about the city and promoted Cavafy's work.[29]

Lawrence Durrell, working for the British in Alexandria during World War II, achieved international success with the publication of The Alexandria Quartet (1957–1960).[30]

Recent discoveries

In July 2018, archaeologists led by Zeinab Hashish announced the discovery of a 2.000-year-old 30-ton black granite sarcophagus. It contained three damaged skeletons in red-brown sewage water. According to archaeologist Mostafa Waziri, the skeletons looked like a family burial with a middle-aged woman and two men. Researchers also revealed a small gold artifact and three thin sheets of gold.[31][32][33]

See also

References

- "Alexandria, Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Christine Favard-Meeks & Dimitri Meeks, "The heir of the Delta"; in Jacob & de Polignac (1992/2000); pp. 20–29.

- François de Polignac, "The shadow of Alexander"; in Jacob & de Polignac (1992/2000); pp. 32–42. "Ultimately, the monument gave rise to numerous allegorical interpretations where it stood as the axis of the planet, the central point around which the whole universe was ordered. Nothing, however, could better signify this change than the placing of Alexandria's tomb within the city. The dynasty and capital, built upon such a prestigious relic, could, more than any other, claim to hold up and preserve the universal vision that attached to a royalty inherited from the deceased. This encompassed, at one and the same time, the Alexander of 331, Macedonian king and founder of the city, the Alexander of 323, son of Ammon, universal conqueror and god unvanquished, and finally the Alexander of 321, protector of Egypt who, by coming back from Memphis, transferred the heritage of the pharaohs to the heart of Alexandria."

- Mostafa el-Abbai, "The Island of Pharos in Myth and History"; in Harris & Ruffini (2004), p. 286–287.

- Walter Scheidel, "Creating a Metropolis: A Comparative Demographic Perspective"; in Harris & Ruffini (2004), p. 2. "The true extent of our ignorance about the most fundamental demographic features of Alexandria is well brought out by Fraser's massive tomes on the history of the city under the Ptolemies. 1,100 pages of text and notes cannot change the fact that 'the development of Alexandria as a city largely escapes us'. Among other things, we do not know how many people were initially settled at the site; how their numbers changed over time; where successive generations of immigrants came from; and what the maximum size of the population was, or when it was reached. Nor do we know whether it was the food supply, demographic conditions, or other variables that mediated the city's growth, or how its development affected the urban system of Egypt as a whole."

- Diodorus Siculus, 17, 52.6.

- Erskine, Andrew (April 1995). "Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser". Culture and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria. 42 (1). pgs 38–48 [42].

One effect of the newly created Hellenistic kingdoms was the imposition of Greek cities occupied by Greeks on an alien landscape. In Egypt there was a native Egyptian population with its own culture, history, and traditions. The Greeks who came to Egypt, to the court or to live in Alexandria, were separated from their original cultures. Alexandria was the main Greek city of Egypt and within it there was an extraordinary mix of Greeks from many cities and backgrounds.

- Walter Scheidel, "Creating a Metropolis: A Comparative Demographic Perspective"; in Harris & Ruffini (2004), p. 23.

- Strabo, Geographica, XIV.5.13 ("With the Alexandrians, however, both things take place, for they admit1 many foreigners and also send not a few of their own citizens abroad"); quoted in Luciano Canfora, "The world in a scroll"; in Jacob & de Polignac (1992/2000); pp. 43–55.

- Walter Scheidel, "Creating a Metropolis: A Comparative Demographic Perspective"; in Harris & Ruffini (2004), p. 25. "I suspect that despite their lack of civic status, Egyptians were presumably more numerous than any other group. In contrast to their later prominence, there is no good sign of a sizeable Jewish community in the third century BCE."

- Erskine, Andrew (April 1995). "Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser". Culture and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria. 42 (1). pgs 38–48 [42–43].

The Ptolemaic emphasis on Greek culture establishes the Greeks of Egypt with an identity for themselves. […] But the emphasis on Greek culture does even more than this – these are Greeks ruling in a foreign land. The more Greeks can indulge in their own culture, the more they can exclude non-Greeks, in other words Egyptians, the subjects whose land has been taken over. The assertion of Greek culture serves to enforce Egyptian subjection. So the presence in Alexandria of two institutions devoted to the preservation and study of Greek culture acts as a powerful symbol of Egyptian exclusion and subjection. Texts from other cultures could be kept in the library, but only once they had been translated, that is to say Hellenized.

[…] A reading of Alexandrian poetry might easily give the impression that Egyptians did not exist at all; indeed Egypt itself is hardly mentioned except for the Nile and the Nile flood, […] This omission of the Egypt and Egyptians from poetry masks a fundamental insecurity. It is no coincidence that one of the few poetic references to Egyptians presents them as muggers. - Alessandro Hirata, Die Generalklausel zur Hybris in der alexandrinischen Dikaiomata, Savigny Zeitschrift 125 (2008), 675-681.

- Erskine, Andrew (April 1995). "Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser". Culture and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria. 42 (1). pgs. 38–48 [44].

This procession is very revealing about Ptolemaic Egypt. In essence it is a religious procession, but its magnificence and its content transform it into something more than this. For anyone watching, whether they are foreigners, who might be paying a visit or there on a diplomatic mission, or Alexandrian Greeks or native Egyptians, the procession hammers out the message of Ptolemy’s enormous wealth and power. For Alexandrian Greeks, both those watching and those taking part, it will be a celebration and affirmation of Greekness. But it is even more than this it is also a procession shouting out Greek superiority to any native Egyptians who happen to be in the vicinity. Thus in a popular, visual form the procession embodies those same elements which were observed above in the case of the Library and Museum.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LI, 16

- Haas (1997), p. 9.

- Stiros, Stathis C.: "The AD 365 Crete earthquake and possible seismic clustering during the fourth to sixth centuries AD in the Eastern Mediterranean: a review of historical and archaeological data", Journal of Structural Geology, Vol. 23 (2001), pp. 545-562 (549 & 557)

- Mediterranean's 'horror' tsunami may strike again, New Scientist online, March 10, 2008.

- MacLeod, Roy (2004). The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World. I. B. Tauris. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1850435945. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Marjorie Venit (2012). "Alexandria". In Riggs, Christina (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0199571451.

- Haas (1997), pp. 17–18. "This quarter is especially noteworthy as it provides our first archaeological window onto urban life in late antique Alexandria. Workshops and street-front stores as well as private dwellings complement the depictions in literary sources of the city's varied commercial and social life. An elegant theaterlike structure was uncovered, along with a large imperial bath complex and lecture halls, the latter being unprecedented archaeological evidence for the city's intellectual reputation. Unexpected discoveries from the inhabited quarter include frescoes and other wall decorations that provide clear evidence for the development of Coptic artistic forms in a cosmopolitan urban setting—not just in the chora of Middle and Upper Egypt."

- Haas (1997), p.347

- "The Lighthouse of Alexandria". Archived from the original on 2007-08-24. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- Reimer (1997), p. 23. "Nevertheless, throughout most of the period of the Mamluk sultanate (1250–1517), the city of Alexandria was a busy entrepôt for trade between Egypt and Europe. A great assortment of countries had agents in the city, although the European trade was dominated by merchants from the city-states of northern Italy, principally Venetians, Genoese, Florentines, and Pisans. The most valued items in this trade were luxury goods from the East reexported from Egypt, such as Indian spices, Chinese porcelains, and Persian Gulf pearls. European merchants in their turn sold wood, furs, cloth, and slaves in Alexandria. The various tariffs imposed upon this trade generated immense sums that were essential to the fiscal health of the Mamluk state."

- Reimer (1997), p. 27–30.

- Reimer (1997), pp. 30–31.

- Wright, William (2009). A Tidy Little War: The British Invasion of Egypt, 1882. Spellmount. p. 107.

- Polyzoides (2014), pp. 7–8.

- "محافظة الإسكندرية". Archived from the original on 2007-01-02. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- Polyzoides (2014), pp. 17–26.

- Polyzoides (2014), pp. 27–29.

- Specia, Megan (2018-07-19). "Inside That Black Sarcophagus in Egypt? 3 Mummies (and No Curses) (Published 2018)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- Daley, Jason. "Scientists Begin Unveiling the Secrets of the Mummies in the Alexandria 'Dark Sarcophagus'". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- August 2018, Owen Jarus 20. "That Massive Black Sarcophagus Contained 3 Inscriptions. Here's What They Mean". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

Bibliography

- Haas, Christopher (1997). Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801853777

- Harris, W.V.. & Giovanni Ruffini, eds. (2004). Ancient Alexandria Between Egypt and Greece. Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition, Vol. XXVI. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 90 04 14105 7.

- Jacob, Christian, & François de Polignac, eds. (1992/2000). Alexandria, third century BC: The knowledge of the world in a single city. Translated by Colin Clement. Alexandria: Harpocrates Publishing, 2000. ISBN 977-5845-03-3. Originally published in 1992 as Alexandrie IIIe siècle av. J.-C., tous les savoirs du monde ou l'rêve d'universalité des Ptolémées.

- McKenzie, Judith (2007). The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, 300 B.C.–A.D. 700. Pelican History of Art, Yale University Press.

- Polyzoides, A. J. (2014). Alexandria: City of Gifts and Sorrows: From Hellenistic Civilization to Multiethnic Metropolis. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-78284-156-2

- Reimer, Michael J. (1997). Colonial Bridgehead: Government and Society in Alexandria, 1807–1882. Boulder, Colorado: WestviewPress (HarperCollins). ISBN 0-8133-2777-6

- Pollard, Justin. Reid, Howard (2006). The Rise and Fall of Alexandria Birthplace of the Modern World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-143-11251-8

- Scwartz, Seth. (2014). The Ancient Jews from Alexander to Muhammad: Key themes in Ancient History Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-66929-1

External links

- Centre d'Études Alexandrines – established by Jean-Yves Empereur – site (in French) has useful articles and files

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Alexandria. |