Hildenbrandia

Hildenbrandia is a genus of thalloid red alga comprising 26 species. The slow-growing, non-mineralized thalli take a crustose form.[1] Hildenbrandia reproduces by means of conceptacles and produces tetraspores.

| Hildenbrandia | |

|---|---|

| |

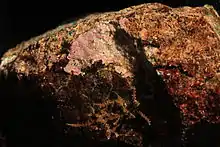

| The darker red alga encrusting this rock fragment is H. crouaniorum | |

| |

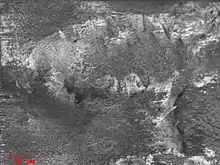

| SEM of a H. rivularis gemma. Scale bar: 50 μm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Archaeplastida |

| Division: | Rhodophyta |

| Class: | Florideophyceae |

| Order: | Hildenbrandiales |

| Family: | Hildenbrandiaceae |

| Genus: | Hildenbrandia Nardo, 1834 |

Morphology

Hildenbrandia cells are around 3–5 μm in diameter and the filaments are around 50–75 μm in height.[2]

The thallus comprises two layers; the hypothallus, which attaches to the rock, and the perithallus, a pseudoparenchymous layer comprising vertical filaments, which unlike coralline red algae is not further differentiated.[3][4]

Growth

Hildenbrandia comprises orderly layers of vertical oblong cells with thick vegetative cell walls, occasionally connected by secondary pit connections with pit plugs in the septal pores.[5] It grows at its margins, away from the centre, and is able to quickly repair any gaps arising by regenerating from a basal layer of cells.[6] As plants become more mature, they become multi-layered and strongly pigmented near their centres, whilst their single-layered margins begin to grow more slowly.[6] Multi-layered areas may develop in the margins; these will detach and float away as gemmae to form new colonies, leaving a single layer of cells beneath them once they separate from the host plant.[6]

Newly settled gemmae form rhizoids.[7]

Conceptacles develop in a haphazard manner; cells in conceptacle regions deform one another and become less regularly shaped as they grow larger.[5]

In a similar fashion to the coralline algae, the outer layer of the thallus is shed seasonally, presumably to avoid colonization by epiphytes.[8]

Habitat

The freshwater species H. rivularis[6] and H. angularis[7] seems to form a clade,[9] and require an alkaline pH and hard water, preferring clean water.[10] Unlike most other freshwater red algae (which prefer running water), H. rivularis prefers still water, particularly shady lakes or ponds.[10] H. rubra and other marine species are found in brackish waters, but freshwater / gemma-bearing species cannot tolerate even moderate salinities.[11] The genus is often found in a symbiotic partnership with fungi.[12] Hildenbrandia has a remarkable tolerance to stresses including extreme temperatures, desiccation, and Ultra-violet light; it can be up and photosynthesizing near full capacity just minutes after being cooled to −17 °C or subjected to extreme salinities.[13]

Reproduction

Sexual reproduction has never been observed in any Hildenbrandia species.[11] It can reproduce by splitting into multiple colonies by fragmentation, or via stolons (i.e. sending out lateral branches) or gemmae.[6]

Marine Hildenbrandia, on the other hand, reproduce by means of tetraspores that are produced within the thallus by conceptacles.[7]

Systematics

The genus contains these species[14] (this list is out of date):

- H. angolensis

- H. arracana

- H. canariensis

- H. crouanii

- H. crouaniorum

- H. dawsonii

- H. deusta

- H. expansa

- H. galapagensis

- H. kerguelensis

- H. lecannellieri

- H. lithothamnioides

- H. nardiana

- H. occidentalis

- H. pachythallos

- H. patula

- H. prototypus

- H. ramanaginaii

- H. rivularis

- H. rosea

- H. rubra

- H. sanjuanensis

- H. yessoensis

Stonehenge

The presence of H. rivularis near Stonehenge has been put forward as a reason for the site's perceived mystical properties. Flint in the Blick Mead spring pools near to the henge takes on a pink hue a couple of hours after being taken out of water due to the presence of the algae. It is assumed that ancient hunter-gatherers would have seen the rocks as having magical properties and would have deemed the site worthy of interest.[15] [16]

References

- Dethier, M. (1994). "The ecology of intertidal algal crusts: variation within a functional group". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 177: 37–71. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(94)90143-0.

- Sherwood, A.; Sheath, R. (2000). "Biogeography and systematics of Hildenbrandia (Rhodophyta, Hildenbrandiales) in Europe: inferences from morphometrics and rbcL and 18S rRNA gene sequence analyses". European Journal of Phycology. 35 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1080/09670260010001735731.

- "Hildenbrandia Ben: Morphology". washington.edu.

- Cabioch, J.; Giraud, G. (1982). "La structure hildenbrandioïde, stratégie adaptative chez les Florideés". Phycologia (in French). 21 (3): 308–315. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-21-3-307.1.

- Pueschel, C. (1982). "Ultrastructural observations of tetrasporangia and conceptacles in Hildenbrandia (Rhodophyta: Hildenbrandiales)". European Journal of Phycology. 17 (3): 333–341. doi:10.1080/00071618200650331.

- Wayne Nichols, H. (1965). "Culture and development of Hildenbrandia rivularis from Denmark and North America". American Journal of Botany. 52 (1): 9–15. doi:10.2307/2439969. JSTOR 2439969.

- Sherwood, A. R.; Sheath, R. G. (2000). "Microscopic analysis and seasonality of gemma production in the freshwater red alga Hildenbrandia angolensis (Hildenbrandiales, Rhodophyta)". Phycological Research. 48 (4): 241–249. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1835.2000.00208.x. S2CID 84193742.

- Pueschel, C. (1988). "Cell sloughing and chloroplast inclusions in Hildenbrandia rubra (Rhodophyta, Hildenbrandiales)". European Journal of Phycology. 23: 17–23. doi:10.1080/00071618800650021.

- Sherwood, A. R.; Sheath, R. G. (2003). "Systematics of the Hildenbrandiales (Rhodophyta): gene sequence and morphometric analyses of global collections". Journal of Phycology. 39 (2): 409–422. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.01050.x. S2CID 86786840.

- Eloranta, P.; Kwandrans, J. (2004). "Indicator value of freshwater red algae in running waters for water quality assessment" (PDF). International Journal of Oceanography and Hydrobiology. XXXIII (1): 47–54. ISSN 1730-413X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-10-27.

- Sherwood, A. R.; Shea, T. B.; Sheath, R. G. (2002). "European freshwater Hildenbrandia (Hildenbrandiales, Rhodophyta) has not been derived from multiple invasions from marine habitats". Phycologia. 41: 87–95. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-41-1-87.1. S2CID 84894072.

- Saunders, G. W.; Bailey, J. C. (1999). "Molecular systematic analyses indicate that the enigmatic Apophlaea is a member of the Hildenbrandiales (Rhodophyta, Florideophycidae)". Journal of Phycology. 35: 171–175. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.1999.3510171.x. S2CID 84758802.

- Garbary, D. (2007). "The Margin of the Sea". Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology. 11. pp. 173–191. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6112-7_9. ISBN 978-1-4020-6111-0.

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. (2008). "Hildenbrandia". AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- "Mesolithic settlement near Stonehenge: excavations at Blick Mead, Vespasian's Camp, Amesbury" (PDF). www.silversaffron.co.uk.

- Jacques, David (2014). "Mesolithic settlement near Stonehenge: excavations at Blick Mead, Vespasian's Camp, Amesbury". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. 107: 7–27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hildenbrandia. |

- Benjamin Weisgall. "Hildenbrandia spp. : the immortal red crust". FHL Marine Botany: an excellent, accessible overview of the genus.

- Images of Hildenbrandia at Algaebase