Hildebrandslied

The Hildebrandslied (German: [ˈhɪldəbʁantsˌliːt]; Lay or Song of Hildebrand) is a heroic lay written in Old High German alliterative verse. It is the earliest poetic text in German, and it tells of the tragic encounter in battle between a father (Hildebrand) and a son (Hadubrand) who does not recognize him. It is the only surviving example in German of a genre which must have been important in the oral literature of the Germanic tribes.

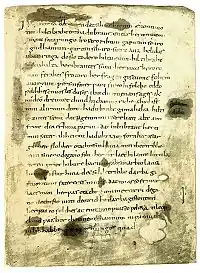

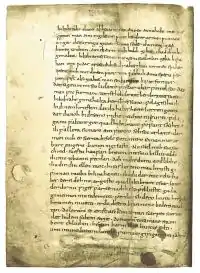

The text was written in the 830s on two spare leaves on the outside of a religious codex in the monastery of Fulda. The two scribes were copying from an unknown older original, which itself must ultimately have derived from oral tradition. The story of Hildebrand and Hadubrand almost certainly goes back to 7th or 8th century Lombardy and is set against the background of the historical conflict between Theodoric and Odoacer in 5th century Italy. The fundamental story of the father and son who fail to recognize each other on the battlefield is much older and is found in a number of Indo-European traditions.

The manuscript itself has had an eventful history: twice looted in war but eventually returned to its rightful owner, twice moved to safety shortly before devastating air-raids, repeatedly treated with chemicals by 19th century scholars, once almost given to Hitler, and torn apart and partly defaced by dishonest book dealers. It now resides, on public display, in a secure vault in the Murhard Library in Kassel.

The text is highly problematic: as a unique example of its genre, with many words not found in other German texts, its interpretation remains controversial. Difficulties in reading some of the individual letters and identifying errors made by the scribes mean that a definitive edition of the poem is impossible. One of the most puzzling features is the dialect, which shows a mixture of High German and Low German spellings which cannot represent any actually spoken dialect.

In spite of the many uncertainties over the text and continuing debate on the interpretation, the poem is widely regarded as the first masterpiece of German literature.

There can surely be no poem in world literature the exposition and development of which are terser and more compelling.

Synopsis

The opening lines of the poem set the scene: two warriors meet on a battlefield, probably as the champions of their two armies.

As the older man, Hildebrand opens by asking the identity and genealogy of his opponent. Hadubrand reveals that he did not know his father but the elders told him his father was Hildebrand, who fled eastwards in the service of Dietrich (Theodoric) to escape the wrath of Otacher (Odoacer), leaving behind a wife and small child. He believes his father to be dead.

Hildebrand responds by saying that Hadubrand will never fight such a close kinsman (an indirect way of asserting his paternity) and offers gold arm-rings he had received as a gift from the Lord of the Huns (the audience would have recognized this as a reference to Attila, whom according to legend Theodoric served).

Hadubrand takes this as a ruse to get him off guard and belligerently refuses the offer, accusing Hildebrand of deception, and perhaps implying cowardice. Hildebrand accepts his fate and sees that he cannot honourably refuse battle: he has no choice but to kill his own son or be killed by him.

They start to fight, and the text concludes with their shields smashed. But the poem breaks off in the middle of a line, not revealing the outcome.

The text

The text consists of 68 lines of alliterative verse, though written continuously with no consistent indication of the verse form. It breaks off in mid-line, leaving the poem unfinished at the end of the second page. However, it does not seem likely that much more than a dozen lines are missing.

The poem starts:

Ik gihorta ðat seggen |

I heard tell |

.jpg.webp)

Structure

The basic structure of the poem comprises a long passage of dialogue, framed by introductory and closing narration. [3] A more detailed analysis is offered by McLintock:[4][5]

- Introductory narrative (ll. 1–6): The warriors meet and prepare for combat.

- Hildebrand's 1st speech, with introductory formula and characterization (ll. 7–13): Hildebrand asks his opponent's identity.

- Hadubrand's 1st speech, with introductory formula (ll. l4–29): Hadubrand names himself, tells how his father left with Dietrich, and that he believes him to be dead.

- Hildebrand's 2nd Speech (ll. 30–32): Hildebrand indicates his close kinship with Hadubrand.

Narrative (ll. 33–35a): Hildebrand removes an arm-ring

Hildebrand's 3rd speech (l. 35b): and offers it to Hadubrand. - Hadubrand's 2nd speech, with introductory formula (ll. 36–44): Hadubrand rejects the proffered arm-ring, accuses Hildebrand of trying to trick him, and reasserts his belief that his father is dead.

- Hildebrand's 4th speech, with introductory formula (ll.45–62): Hildebrand comments that Hadubrand's good armour shows he has never been an exile. Hildebrand accepts his fate, affirming that it would be cowardly to refuse battle and challenging Hadubrand to win his armour.

- Closing narrative (ll. 63–68): The warriors throw spears, close for combat and fight until their shields are destroyed.

While this structure accurately represents the surviving manuscript text, many scholars have taken issue with the position of ll. 46–48 ("I can see from your armour that you have a good lord at home and that you were never exiled under this regime").[6] In these lines, as it stands, Hildebrand comments on Hadubrand's armour and contrasts his son's secure existence with his own exile. Such a measured observation perhaps seems out of keeping with the confrontational tone of the surrounding conversation.[7] Many have suggested, therefore, that the lines should more correctly be given to Hadubrand — from his mouth they become a challenge to Hildebrand's story of exile — and placed elsewhere. The most widely accepted placing is after l. 57, after Hildebrand has challenged Hadubrand to take an old man's armour.[6][8][9] This has the advantage that it seems to account for the extraneous quad Hiltibrant in ll. 49 and 58, which would normally be expected to introduce a new speaker and seem redundant (as well as hypermetrical) in the manuscript version.[10] Alternatively, De Boor would place the lines earlier, before l.33, where Hildebrand offers an arm-ring.[7] However, more recently the trend has been to accept the placing of these lines and see the task as making sense of the text as it stands.[11][12]

Problems

In spite of the text's use of spare space in an existing manuscript, there is evidence that it was prepared with some care: the two sheets were ruled with lines for the script, and in a number of places letters have been erased and corrected.[13][14]

Nonetheless, some features of the text are hard to interpret as anything other than uncorrected errors. Some of these are self-evident copying errors, due either to misreading of the source or the scribe losing his place. An example of the latter is the repetition of darba gistuotun in l. 26b, which is hypermetrical and gives no sense – the copyist's eye must have been drawn to the Detrihhe darba gistuontun of l.23 instead of to the Deotrichhe in l.26b.[15] Other obvious copying errors include mih for mir (l.13) and fatereres for fateres (l.24).[16]

It seems also that the scribes were not entirely familiar with the script used in their source. The inconsistencies in the use and form of the wynn-rune, for example — sometimes with and sometimes without an acute stroke above the letter, once corrected from the letter p — suggest this was a feature of the source which was not a normal part of their scribal repertoire.[17]

While these issues are almost certainly the responsibility of the Fulda scribes, in other cases an apparent error or inconsistency might already have been present in their source. The variant spellings of the names Hiltibrant/Hiltibraht, Hadubrant/Hadubraht, Theotrihhe/Detriche/Deotrichhe. were almost certainly present in the source.[18][19] In several places, the absence of alliteration linking the two halves of a line suggests missing text, so ll.10a and 11b, which follow each other in the manuscript (fıreo ın folche • eddo welıhhes cnuosles du sis, "who his father was in the host • or what family you belong to")), do not make a well-formed alliterating line and in addition display an abrupt transition between third-person narrative and second-person direct speech.[6][20] The phrase quad hiltibrant ("said Hildebrand") in lines 49 and 58 (possibly line 30 also) breaks the alliteration and seems to be a hypermetrical scribal addition to clarify the dialogue.[21]

In addition to errors and inconsistencies, there are other features of the text which make it hard to interpret. Some words are hapax legomena (unique to the text), even if they sometimes have cognates in other Germanic languages.[22][23] Examples include urhetto ("challenger"), billi ("battle axe") and gudhamo ("armour").[24] Since the Hildebrandslied is the earliest poetic text and the only heroic lay in German, and is the oldest heroic lay in any Germanic language, it is difficult to establish whether such words enjoyed broader currency in the 9th century or belonged to a (possibly archaic) poetic language.[25]

The text's punctuation is limited: the only mark used is a sporadic punctus (•), and identifying clause and sentence boundaries is not always straightforward. Since the manuscript gives no indication of the verse form, line divisions are the judgments of modern editors.[26][27]

Finally, the mixture of dialect features, mostly Upper German but with some highly characteristic Low German forms, means that the text could never have reflected the spoken language of an individual speaker and never been meant for performance.[28]

Frederick Norman concludes, "The poem presents puzzles alike to palaeographers, linguists and literary historians." [29]

The manuscript

Description

The manuscript of the Hildebrandslied is now in the Murhardsche Bibliothek in Kassel (signature 2° Ms. theol. 54).[30] The codex consists of 76 folios containing two books of the Vulgate Old Testament (the Book of Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus) and the homilies of Origen. It was written in the 820s in Anglo-Saxon minuscule and Carolingian minuscule hands. The text of the Hildebrandslied was added in the 830s on the two blank outside leaves of the codex (1r and 76v).[31][32]

The poem breaks off in the midst of the battle and there has been speculation that the text originally continued on a third sheet (now lost) or on the endpaper of the (subsequently replaced) back cover.[33][34] However, it is also possible that the text was being copied from an incomplete original or represented a well-known episode from a longer story.[35]

The Hildebrandslied text is the work of two scribes, of whom the second wrote only seven and a half lines (11 lines of verse) at the beginning of the second leaf. The scribes are not the same as those of the body of the codex.[31] The hands are mainly Carolingian minuscule. However, a number of features, including the wynn-rune (ƿ) used for w suggest Old English influence, not surprising in a house founded by Anglo-Saxon missionaries.

The manuscript pages now show a number of patches of discoloration. These are the results of attempts by earlier scholars to improve the legibility of the text with chemical agents.[36]

History

The manuscript's combination of Bavarian dialect and Anglo-Saxon palaeographic features make Fulda the only monastery where it could have been written. With its missionary links to North Germany, Fulda is also the most likely origin for the earlier version of the poem in which Old Saxon features were first introduced.[37] In around 1550 the codex was listed in the monastery's library catalogue.[31]

In 1632, during the Thirty Years War, the monastery was plundered and destroyed by Hessian troops. While most of the library's manuscripts were lost, the codex was among a number of stolen items later returned to the Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel and placed in the Court Library.[31][38] In the aftermath of the political crisis of 1831, under the terms of Hesse's new constitution the library passed from the private possession of the landgraves to public ownership and became the Kassel State Library (Landesbibliothek).[39][40]

In 1937 there was a proposal to make a gift of the manuscript to Adolf Hitler, but this was thwarted by the library's director, Wilhelm Hopf.[41]

At the start of the Second World War, the manuscript, along with 19 others, was moved from the State Library to the underground vault of a local bank. This meant that it was not harmed in the Allied bombing raid in September 1941, which destroyed almost all the library's holdings.[42] In August 1943 the codex (along with the Kassel Willehalm codex) was moved for safe keeping out of Kassel completely to a bunker in Bad Wildungen, south-west of the city, just in time to escape the devastating air-raids the following October, which destroyed the whole of the city centre. After the capture of Bad Wildungen by units of the US Third Army in March 1945, the bunker was looted and the codex went missing. An official investigation by the US Military Government failed to discover its fate.[43][44][45] In November 1945 it was sold by US army officer Bud Berman to the Rosenbach Company, rare book dealers in Philadelphia.[46] At some point the first folio, with the first page of the Hildebrandslied, was removed (presumably in order to disguise the origin of the codex, since that sheet carried the library's stamp). In 1950, even though the Pierpont Morgan Library had raised questions about the provenance of the codex and the Rosenbachs must have known it was looted, it was sold to the Californian bibliophile Carrie Estelle Doheny and placed in the Edward Laurence Doheny Memorial Library in Camarillo.[47] In 1953 the codex was traced to this location, and in 1955 it was returned to Kassel. However, it was only in 1972 that the missing first folio (and the Kassel Willehalm) was rediscovered in the Rosenbach Museum and reunited with the codex.[48][49]

The manuscript is now on permanent display in the Murhard Library.[50]

Reception

Attention was first drawn to the codex and the Hildebrandslied by Johann Georg von Eckhart, who published the first edition of the poem in 1729.[51] This included a hand-drawn facsimile of the start of the text, with a full transcription, a Latin translation and detailed glosses of the vocabulary.[52] His translation shows a considerable range of errors and misconceptions (Hildebrand and Hadubrand are seen as cousins, for example, who meet on the way to battle).[53] Also, he did not recognize the text as verse, and its historical significance consequently remained unappreciated.[54]

Both the fact and the historical significance of the alliterative verse form were first recognized by the Brothers Grimm in their 1812 edition,[55] which also showed improved transcription and understanding compared to Eckhart's,[56] This is generally regarded as the first scholarly edition and there have been many since.[57][58]

Wilhelm Grimm went on to publish the first facsimile of the manuscript in 1830,[59] by which time he had recognized the two different hands and the oral origin of the poem.[56][60] He had also become the first to use reagents in an attempt to clarify the text.[61]

The first photographic facsimile was published by Sievers in 1872.[62] This clearly shows the damage caused by the reagents used by Grimm and his successors.[63]

The language

One of the most puzzling features of the Hildebrandslied is its language, which is a mixture of Old High German (with some specifically Bavarian features) and Old Saxon.[64] For example, the first person pronoun appears both in the Old Saxon form ik and the Old High German ih. The reason for the language mixture is unknown, but it seems certain it cannot have been the work of the last scribes and was already present in the original which they copied.

The Old Saxon features predominate in the opening part of the poem and show a number of errors, which argue against an Old Saxon original. The alliteration of riche and reccheo in line 48 is often regarded as conclusive: the equivalent Old Saxon forms, rīke and wrekkio, do not alliterate and would have given a malformed line.[65] Earlier scholars envisaged an Old Saxon original, but an Old High German original is now universally accepted.[66]

The errors in the Old Saxon features suggest that the scribe responsible for the dialect mixture was not thoroughly familiar with the dialect. Forms such as heittu (l.17) and huitte (l.66) (Modern German heißen and weiß) are mistakes for Old Saxon spellings with a single ⟨t⟩. They suggest a scribe who does not realise that Old High German zz, resulting from the High German consonant shift, corresponds to t in Old Saxon in these words, not tt, that is, a scribe who has limited first-hand knowledge of Old Saxon.

The origin of the Dietrich legend in Northern Italy also suggests a southern origin is more likely.

The East Franconian dialect of Fulda was High German, but the monastery was a centre of missionary activity to Northern Germany. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume there was some knowledge of Old Saxon there, and perhaps even some Old Saxon speakers. However, the motivation for attempting a translation into Old Saxon remains inscrutable, and attempts to link it with Fulda's missionary activity among the Saxons remain speculative.

An alternative explanation treats the dialect as homogeneous, interpreting it as representative of an archaic poetic idiom.[67]

Analogues

Germanic

Legendary material about Hildebrand survived in Germany into the 17th Century[68] and also spread to Scandinavia, though the forms of names vary. A number of analogues either portray or refer to Hildebrand's combat with his son:[69]

- In the 13th century Old Norse Thiðrekssaga, Hildibrand defeats his son, Alibrand. Alibrand offers his sword in surrender but attempts to strike Hildibrand as he reaches for it. Hildibrand taunts him for having been taught to fight by a woman, but then asks if he is Alibrand and they are reconciled.[70][71]

- The Early New High German Jüngeres Hildebrandslied (first attested in the fifteenth century) tells a similar story of the treacherous blow, the taunt that the son was taught to fight by a woman, and the final reconciliation.

- In the 14th century Old Norse Ásmundar saga kappabana, Hildebrand's shield bears paintings of the warriors he has killed, which include his own son.

- In the Faroese ballad Snjólvskvæði, Hildebrand is tricked into killing his son.[72][73]

- In Book VII of the Gesta Danorum (early 13th century), Hildiger reveals as he is dying that he has killed his own son.

Other Indo-European

There are three legends in other Indo-European traditions about an old hero who must fight his son and kills him after distrusting his claims of kinship:[74][75]

- In Irish medieval literature, the hero Cú Chulainn kills his son Conlaí.[76]

- In the Persian epic tale Shahnameh, Rostam kills his son Sohrab.

- In a popular Rus' Bylina Ilya Muromets kills his son Podsokolnik.

The Ending

While the conclusion of the Hildbrandslied is missing, the consensus is that the evidence of the analogues supports the death of Hadubrand as the outcome of the combat.[77] Even though some of the later medieval versions end in reconciliation, this can be seen as a concession to the more sentimental tastes of a later period.[78] The heroic ethos of an earlier period would leave Hildebrand no choice but to kill his son after the dishonourable act of the treacherous stroke. There is some evidence that this original version of the story survived into the 13th Century in Germany: the Minnesänger Der Marner refers to a poem about the death of young Alebrand.[79][80]

Origin and transmission

Origins

The poet of the Hildebrandslied has to explain how father and son could fail to know each other. To do so, he has set the encounter against the background of the Dietrich legend based on the life of Theodoric the Great.

Historically, Theodoric invaded Italy in 489, defeated and killed the ruling King of Italy, Odoacer, to establish his own Ostrogothic Kingdom. Theodoric ruled from 493 to 526, but the kingdom was destroyed by the Eastern Emperor Justinian I in 553, and thereafter the invading Lombards seized control of Northern Italy. By this time the story of Theodoric's conflict with Odoacer had been recast, contrary to historical fact, as a tale of Theodoric's return from exile, thus justifying his war on Odoacer as an act of revenge rather than an unprovoked attack.

In the Dietrich legend, Hildebrand is a senior warrior in Theodoric's army (in the Nibelungenlied he is specifically Dietrich's armourer). However, there is no evidence of a historical Hildebrand, and since names in -brand are overwhelmingly Lombard rather than Gothic, it seems certain that the tale of Hildebrand and Hildebrand was first linked with the legend of Theodoric's exile by a Lombard rather than a Gothic poet.[81] [82] However, attention has been drawn to the fact that one of Theodoric's' generals bore the nickname Ibba. While this could not have been a nickname for Hildebrand among the Goths, it might have been so interpreted later among the Lombards.[83]

In the later re-tellings of the Dietrich legend, Theodoric is driven into exile not by Odoacer but by Ermanaric (in historical fact a 4th century King of the Goths), which suggests that the earliest version of the Hildebrandslied was created when the legend still had some loose connection to the historical fact of the conflict with Odoacer. This first version of the story would probably have been composed some time in the 7th century, though it is impossible how close it is in form to the surviving version.[84]

Transmission

The oral transmission of a Lombard poem northwards to Bavaria would have been facilitated by the fact that the Langobardic and Bavarian dialects were closely related forms of Upper German, connected via the Alpine passes. The two peoples were also connected by dynastic marriages and cultural contacts throughout the history of the Lombard Kingdom.[85] By the late 8th century, both the Lombard Kingdom and the Duchy of Bavaria had been incorporated into the Frankish Empire.

The evidence of the phonology of the Hildebrandslied is that the first written version of this previously oral poem was set down in Bavaria in the 8th century.

While Fulda was an Anglo-Saxon foundation located in the East Franconian dialect area, it had strong links with Bavaria: Sturmi, the first abbot of Fulda, was a member of the Bavarian nobility, and Bavarian monks had a considerable presence at the monastery.[86][87] This is sufficient to account for a Bavarian poem in Fulda by the end of the 8th Century. Fulda also had links with Saxony, evidenced by its missionary activity among the Saxons and the Saxon nobles named in the monastery's annals. This makes it uniquely placed for the attempt to introduce Saxon features into a Bavarian text, though the motivation for this remains a mystery.[86] This Saxonised version then, in the 830s, served as the source of the surviving manuscript.

In summary, the probable stages in transmission are:[78]

- Lombard original (7th century)

- Bavarian adaptation (8th century)

- Reception in Fulda (8th century)

- Saxonised version (c. 800?)

- Surviving version (830s)

Motivation

A final issue is the motivation of the two scribes for copying the Hildebrandslied. Among the suggestions are:[88]

- Antiquarian interest

- A connection with Charlemagne's impulse to collect ancient songs

- Interest in the legal questions the song raises

- A negative example, possibly for missionary purposes: the tragic result of adhering to outdated heroic rather than Christian ethics

- A commentary on the fraught relationship between Louis the Pious and his sons.

There is no consensus on the answer to this question.[89]

Notes

- Hatto 1973, p. 837.

- Braune & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 84.

- Düwel 1989, p. 1243.

- McLintock 1974, p. 73.

- Gutenbrunner 1976, p. 52, offers a similar analysis

- Düwel 1989, p. 1241.

- de Boor 1971, p. 68.

- Steinmeyer 1916, p. 6, apparatus to ll.46–48

- Norman 1973b, p. 43.

- Schröder 1989, p. 26.

- Glaser 1999, p. 557.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, pp. 55–56. "their [the scribes'] knowledge is more trustworthy than our speculation."

- Young & Gloning 2004, p. 46.

- Lehmann 1947, pp. 533–538, discusses the corrections in detail.

- Young & Gloning 2004, p. 47.

- Braune & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 84, notes.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 74.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 75, noting that this variation is found in Fulda charters..

- Norman 1973, p. 37.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 73.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 72.

- Young & Gloning 2004, pp. 43, 52.

- Lühr 1982, p. 353. Lühr calculates that 14–16 of the 230 distinct words in the text are not found elsewhere in Old High German.

- Wolf 1981, p. 118. Wolf finds 11 hapax legomena in the text.

- Young & Gloning 2004, pp. 52–53.

- Düwel 1989, p. 1242.

- Wilkens 1897, pp. 231–232.

- Norman 1973, p. 14. "It is quite impossible that the poem could ever have been recited in the form in which we have it."

- Norman 1973, p. 10.

- Handschriftencensus.

- Wiedemann 1994, p. 72.

- Haubrichs 1995, pp. 116–117.

- Düwel 1989, p. 1240.

- Haubrichs 1995, p. 117.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 47.

- Edwards 2002.

- de Boor 1971, p. 66.

- Popa 2003, p. 33.

- Hopf 1930, p. I, 82 (104).

- Popa 2003, p. 36.

- Popa 2003, p. 16.

- Popa 2003, p. 12.

- Wiedemann 1994, p. XXXIII.

- Popa 2003, p. 5.

- Twaddell 1974, p. 157.

- Popa 2003, p. 215.

- Popa 2003, p. 6.

- Edwards 2002, p. 69.

- Popa 2003, p. 7.

- Popa 2003, p. 221.

- Lühr 1982, p. 16.

- Eckhart 1729.

- Dick 1990, p. 78.

- Dick 1990, pp. 71f..

- Grimm 1812.

- Dick 1990, p. 83.

- Robertson 1911.

- Braune & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 170.

- Grimm 1830.

- Edwards 2002, p. 73.

- Edwards 2002, p. 70.

- Sievers 1872.

- Edwards 2002, p. 71.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 77.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 79.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 78.

- McLintock 1966.

- Curschmann 1989, p. 918.

- Düwel 1989, pp. 1253–1254.

- Bertelsen 1905–1911, pp. 347–351. (Chap. 406–408)

- Haymes 2008, pp. 248–250. (Chap. 406–408)

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, pp. 70–71.

- de Boor 1923, pp. 165–181.

- Heusler 1913–1915, p. 525.

- Hatto 1973.

- Meyer 1904.

- Ebbinghaus 1987, p. 673, who dissents from this view and believes that Hildebrand is the one killed

- de Boor 1971, p. 67.

- Strauch 1876, p. 36.

- Haubrichs 1995, p. 127.

- Norman 1973b, p. 47.

- Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 65.

- Glaser 1999, pp. 555–556.

- Norman 1973b, p. 48.

- Störmer 2007, pp. 68–71.

- Young & Gloning 2004, p. 51.

- Lühr 1982, pp. 251–252.

- Düwel 1989, p. 1253.

- Glaser 1999, p. 560.

References

- de Boor, Helmut (1923–1924). "Die nordische und deutsche Hildebrandsage". Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie. 49–50: 149–181, 175–210. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ——— (1971). Geschichte der deutschen Literatur. Band I. Von Karl dem Großen bis zum Beginn der höfischen Literatur 770–1170. München: C.H.Beck. ISBN 3-406-00703-1.

- Bostock, J. Knight; King, K. C.; McLintock, D. R. (1976). A Handbook on Old High German Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford. pp. 43–82. ISBN 0-19-815392-9. Includes a translation of the Hildebrandslied into English.

- Curschmann M (1989). "Jüngeres Hildebrandslied". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. 3. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 1240–1256. ISBN 3-11-008778-2. With bibliography.

- Dick E (1990). "The Grimms' Hildebrandslied". In Antonsen EH, Marchand JW, Zgusta L (eds.). The Grimm Brothers and the Germanic Past. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: Benjamins. pp. 71–88. ISBN 90-272-4539-8. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Düwel K (1989). "Hildebrandslied". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. 4. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 918–922. ISBN 3-11-008778-2. With bibliography.

- Ebbinghaus EA (1987). "The End of the Lay of Hiltibrant and Hadubrant". In Bergmann R, Tiefenbach H, Voetz L (eds.). Althochdeutsch. 1. Heidelberg: Winter. pp. 670–676.

- Edwards, Cyril (2002). "Unlucky Zeal: The Hildebrandslied and the Muspilli under the Acid". The Beginnings of German Literature. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester New York: Camden House. pp. 65–77. ISBN 1-57113-235-X.

- Glaser, Elvira (1999). "Hildebrand und Hildebrandsled". In Jankuhn, Herbert; Beck, Heinrich; et al. (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (2nd ed.). Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 554–561. ISBN 3-11-016227-X.

- Gutenbrunner, Siegfried (1976). Von Hildebrand und Hadubrand. Lied — Sage — Mythos. Heidelberg: Winter. ISBN 3-533-02362-1.

- Handschriftencensus. "Kassel, Universitätsbibl. / LMB, 2° Ms. theol. 54". Paderborner Repertorium der deutschsprachigen Textüberlieferung des 8. bis 12. Jahrhunderts. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Hatto, A.T. (1973). "On the Excellence of the Hildebrandslied: A Comparative Study in Dynamics" (PDF). Modern Language Review. 68 (4): 820–838. doi:10.2307/3726048. JSTOR 3726048. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- Haubrichs, Wolfgang (1995). Die Anfänge: Versuche volkssprachiger Schriftlichkeit im frühen Mittelalter (ca. 700-1050/60). Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von den Anfängen bis zum Beginn der Neuzeit. 1, part 1 (2nd ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-10700-6.

- Heusler, Andreas (1913–1915). "Hildebrand und Hadubrand". In Hoops, Johannes (ed.). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 2. Strassburg: Trübner. pp. 525–526. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Hopf, Wilhelm W (1930). Die Landesbibliothek Kassel 1580–1930. Marburg: Elwert. Retrieved 7 January 2018. (Page numbers in parenthesis refer to the online edition, which combines the two printed volumes.)

- Lehmann, W. P. (1947). "Notes on the Hildebrandslied". Modern Language Notes. Johns Hopkins University Press. 62 (8): 530–539. doi:10.2307/2908616. ISSN 0149-6611. JSTOR 2908616.

- Lühr, Rosemarie (1982). Studien zur Sprache des Hildebrandliedes (PDF). Frankfurt am Main, Bern: Peter Lang. ISBN 382047157X. Retrieved 15 January 2018. (Page references are to the online edition.)

- McLintock, D. R. (1966). "The Language of the Hildebrandslied". Oxford German Studies. 1: 1–9. doi:10.1179/ogs.1966.1.1.1.

- ——— (1974). "The Politics of the Hildebrandslied". New German Studies. 2: 61–81.

- Norman, Frederick (1973a) [1937]. "Some problems of the Hildebrandslied". In Norman, Frederick; Hatto, A.T. (eds.). Three Essays on the "Hildebrandslied". London: Institute of Germanic Studies. pp. 9–32. ISBN 0854570527.

- ——— (1973b) [1958]. "Hildebrand and Hadubrand". In Norman, Frederick; Hatto, A.T. (eds.). Three Essays on the "Hildebrandslied". London: Institute of Germanic Studies. pp. 33–50. ISBN 0854570527.

- Popa, Opritsa D. (2003). Bibliophiles and bibliothieves : the search for the Hildebrandslied and the Willehalm Codex. Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017730-7. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Schröder, Werner (1999). "Georg Baesecke und das Hildebrandslied". Frühe Schriften zur ältesten deutschen Literatur. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 11–20. ISBN 3-515-07426-0.

- Störmer, Wilhelm (2007). Die Baiuwaren: von der Völkerwanderung bis Tassilo III. Munich: Beck. pp. 978-3-406-47981-6. ISBN 9783406479816. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Strauch, Philipp, ed. (1876). Der Marner. Strassburg: Trübner.

- Twaddell, W.F. (1974). "The Hildebrandlied Manuscript in the U.S.A. 1945–1972". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 73 (2): 157–168.

- Wiedemann, Konrad, ed. (1994). Manuscripta Theologica: Die Handschriften in Folio. Handschriften der Gesamthochschul-Bibliothek Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel. 1. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-3447033558. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Wilkens, Frederick H (1897). "The Manuscript, Orthography, and Dialect of the Hildebrandslied". PMLA. 12 (2): 226–250. doi:10.2307/456134. JSTOR 456134.

- Young, Christopher; Gloning, Thomas (2004). A History of the German Language Through Texts. Abingdon, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18331-6.

Sources

- Braune, Wilhelm; Ebbinghaus, Ernst A., eds. (1994). "XXVIII. Das Hildebrandslied". Althochdeutsches Lesebuch (17th ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 84–85. ISBN 3-484-10707-3. Provides an edited text of the poem which is widely used and quoted. Line numbers for the text of the Hildbrandslied in modern scholarship generally refer to this work and its earlier editions.

- Bertelsen, Henrik (1905–1911). Þiðriks saga af Bern. Samfund til udgivelse af gammel nordisk litteratur, 34. Copenhagen: S.L.Møller. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Broszinski, Hartmut, ed. (2004). Das Hildebrandlied. Faksimile der Kasseler Handschrift mit einer Einführung (3rd revised ed.). Kassel: Kassel University. ISBN 3-89958-008-7. Most recent printed facsimile.

- Eckhart, Johann Georg von (1729). "XIII Fragmentum Fabulae Romanticae, Saxonica dialecto seculo VIII conscriptae, ex codice Casselano". Commentariis de rebus Franciae orientalis. I. Würzburg: University of Würzburg. pp. 864–902. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Grimm, Die Brüder (1812). Die beiden ältesten deutschen Gedichte aus dem achten Jahrhundert: Das Lied von Hildebrand und das Weißenbrunner Gebet zum erstenmal in ihrem Metrum dargestellt und herausgegebn. Cassel: Thurneisen. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Grimm, Wilhelm (1830). De Hildebrando, antiquissimi carminis teutonici fragmentum. Göttingen: Dieterich. Retrieved 20 January 2018. (the first facsimile)

- The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. Garland Library of Medieval Literature, Series B, 56. Translated by Haymes, Edward R. New York: Garland. 1988. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-0824084899.

- Meyer, Kuno (1904). "The Death of Conla". Ériu. 1: 113–121. JSTOR 30007938. Translation reproduced at the Celtic Literature Collective

- Sievers, Eduard (1872). Das Hildebrandslied, die Merseburger Zaubersprüche und da Fränkische Taufgelöbnis mit photographischem Facsimile nach den Handschriften herausgegeben. Halle: Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Steinmeyer, Elias von, ed. (1916). Die kleineren althochdeutschen Sprachdenkmäler. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. pp. 1–15. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

Further reading

- Wolfram Euler: Das Westgermanische – von der Herausbildung im 3. bis zur Aufgliederung im 7. Jahrhundert – Analyse und Rekonstruktion. 244 p., London/Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8. (Including a Langobardic version of the Lay of Hildebrand, pp. 213–215.)

- Willy Krogmann: Das Hildebrandslied in der langobardischen Urfassung hergestellt. 106 p., Berlin 1959.

External links

- Wikisource Hildebrandslied

- Manuscript and transcription (Bibliotheca Augustana)

- English translation by Bruce McMenomy

- Text of first 26 lines with English translation and explanation of individual words

- English verse translation by Francis Wood

- Reading of the Lay of Hildebrand in Old High German and in a hypothetical Langobardic version as reconstructed in 2013 by Wolfram Euler, with subtitles in English.

- Summary and review of Popa's book on the recovery of the MS from the USA by Klaus Graf

- The Danish History/Book VII (English translation of the Gesta Danorum)