Ham House

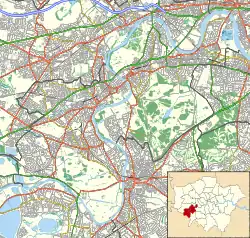

Ham House is a 17th-century house set in formal gardens on the bank of the River Thames in Ham, south of Richmond in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It was completed by 1610 by Thomas Vavasour,[1] an Elizabethan courtier and Knight Marshal to James I, but came to prominence during the 1670s as the home of Elizabeth (Murray) Maitland, the Duchess of Lauderdale and Countess of Dysart and her second husband John Maitland, the Duke of Lauderdale. The house retains many original Jacobean features and furnishings and is claimed by the National Trust to be "unique in Europe as the most complete survival of 17th century fashion and power."[2] The house is designated on the National Heritage List for England as a Grade I listed building.[3] Its park and formal gardens are listed at Grade II* by Historic England in the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[4] In 1948, the house was donated to the National Trust by Sir Lyonel Tollemache and his son Major (Cecil) Lyonel Tollemache.[1]

| Ham House | |

|---|---|

Ham House in 2016, with Coade stone statue of Father Thames, by John Bacon the elder, in the foreground | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Stuart |

| Town or city | Ham, London |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°26′37″N 0°18′59″W |

| Completed | 1610 |

| Client | Sir Thomas Vavasour |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Robert Smythson |

| Other information | |

| Parking | Ham Street |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 10 January 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1080832 |

History

Early years

In the early 17th century the manors of Ham and Petersham were bestowed by James I on his son, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales.[5]

The house was completed in 1610 by Sir Thomas Vavasour, Knight Marshal to James I. It originally comprised an H-plan layout consisting of nine bays and three storeys. The Thames-side location was ideal for Vavasour, allowing him to move between the courts at Richmond, Hampton, London and Windsor as his role required.[6][7] Prince Henry died in 1612, and the lands passed to James' second son, Charles, several years prior to his coronation in 1625.[5] After Vavasour's death in 1620, the house was granted to John Ramsay, 1st Earl of Holderness until his death in 1626.

William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart

In 1626, Ham House was leased to William Murray, courtier, close childhood friend and alleged whipping boy of Charles I. Murray's initial lease was for 39 years and, in 1631, a further 14 years were added. When Gregory Cole, a neighbouring landowner, had to sell his property in Petersham as part of the enclosure of Richmond Park in 1637, he made over the remaining leases on his land to Murray. Shortly afterwards William and his wife Katherine (or Catherine) engaged the services of skilled craftsmen, including the artist Franz Cleyn, to commence improvements on the house as befitting a Lord of the Manors of Ham and Petersham. He extended the Great Hall and added an arch that leads to the ornate cantilever staircase to create a processional route for guests as they approached the dining room on the first floor. He remodelled the Long Gallery and added the adjoining Green Closet that was influenced by Charles I’s own “Cabbonett Room” at Whitehall Palace, to which Murray had donated two pieces.[8]

.jpg.webp)

In 1640 William was also granted a lease on the Manor of Canbury (Kingston) but in the run-up to civil war in 1641 he signed over the house to Katherine and his four daughters, appointing trustees to safeguard the estate for them.[9] The principal of these was Thomas Bruce, Lord Elgin, a relative of his wife and an important Scottish Presbyterian, Parliamentarian supporter and ally of the Puritan party in London.[7]

In 1643, shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, the house and estates were sequestrated,[10] but persistent appeals by Katherine regained them in 1646 on payment of a £500 fine.[11][12] Katherine skilfully defended ownership of the house throughout the Civil War and Commonwealth, and, despite Murray's close ties with the Royalist cause, the house remained in the family's possession. Katherine died at Ham on 18 July 1649 (Charles I had been executed on 30 January of the same year). The Parliamentarians sold off much of the Royal Estate, including the Manors of Ham and Petersham. These, including Ham House, were bought for £1,131.18s on 13 May 1650 by William Adams, the steward acting on behalf of Murray's eldest daughter, Elizabeth and her husband Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Baronet of Helmingham Hall, Suffolk. Ham House became Elizabeth and Lionel's primary residence, as Murray was predominantly exiled in France.[7][13]

Elizabeth (née Murray: 2nd Countess of Dysart) and Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Baronet of Helmingham Hall

Elizabeth continued her parents' political support of the Royalist cause and she and her husband became members of the Sealed Knot. Between 1649 and 1661, Elizabeth bore eleven children, five of whom survived to adulthood; Lionel, Thomas, William, Elizabeth and Catherine. Elizabeth and Lionel made few substantial changes to the house during this busy time. On the Restoration in 1660, Charles II rewarded Elizabeth with a pension of £800 for life and, whilst many of the Parliamentarian sales of Royal lands were put aside, Elizabeth retained the titles to the Manors of Ham and Petersham. In addition, in about 1665, following William's death, Lionel was granted freehold of 75 acres (30 ha; 0.117 sq mi) of land in Ham and Petersham including that surrounding the house and a 61-year lease of 289 acres (117 ha; 0.452 sq mi) of demesne lands. The grant was made in trust to Robert Murray for the daughters of the, then, late Earl of Dysart, "in consideration of the service done by the late Earl of Dysart and his Daughter, and of the losses sustained by them by the enclosure of the New Park."[7][14] Lionel died in 1668, leaving his Ham and Petersham estate to Elizabeth.

Elizabeth and John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale

Elizabeth became associated with John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale. In 1671 Lauderdale was granted by Letters patent full freehold rights to the Manors of Ham and Petersham and the 289 acres of leased land. In 1672 Elizabeth and Lauderdale were married, and, with Lauderdale's part in the CABAL, the family remained close to the heart of court intrigue.

The couple made extensive changes to the house from 1673. Elizabeth consulted her cousin, William Bruce, and Maitland commissioned William Samwell, extending the house into the south part of the "H", making it "double pile", two rooms deep, across its breadth.[6]

The eldest daughter of Elizabeth and Lionel, also named Elizabeth (1659–1735), married Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll in Edinburgh in 1678. Their first child, John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, was born at Ham House in 1680;[15] their second son, Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll was born in the same room a few years later.[7]

On Lauderdale's death in 1682 he left the Ham and Petersham property to Elizabeth, thereby securing the estate for the Tollemache dynasty.[7] However, Elizabeth also inherited her husband's debts including mortgages on his former properties in England and Scotland and her latter years were marred by financial dispute with her brother-in-law, Charles. Even the intervention of the newly crowned James II failed to reconcile them and the matter was finally settled in her favour in the Scottish courts in 1688. Whilst this may have suppressed Elizabeth's lavish lifestyle, she went on to make further alterations to the house at Ham, opening the Hall ceiling and creating the Round Gallery in about 1690.[7] Elizabeth Maitland continued to live at Ham House until her death in 1698.

Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Earl of Dysart

Elizabeth and Lionel Tollemache's eldest son and heir, Lionel, became 3rd Earl of Dysart on his mother's death and inherited Ham House, and the adjoining Estates and Manors of Ham and Petersham. Already the owner of his father's former estates in Suffolk and Northamptonshire, through his marriage to Grace, daughter of Sir Thomas Wilbraham, 3rd Baronet, he had also acquired 20,000 acres (8,100 ha; 31 sq mi) in Cheshire. He only spent short periods at Ham, apparently did little for the upkeep of the house though kept the garden well. He did use his wealth to pay off the interest of the outstanding mortgages but was not considered generous, even with his immediate family. His only son, Lionel, pre-deceased him in 1712 and, on the 3rd Earl's death in 1727, his grandson, also named Lionel, became the 4th Earl of Dysart.[7]

Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart

The 4th Earl inherited the title at the age of 30. After a Grand Tour he married Grace Carteret, daughter of John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville. He undertook extensive repairs of the house, replacing the roof tiles with slates, rebuilding the bays with venetian windows above, replaced mullions with sash windows, and generally repaired decayed timbers, sills and floors where required. On completion of the structural work the house was extensively redecorated and new furniture added; some of this furniture survives, notably the harpsichord and library steps. Despite the modernisation, Lionel also went to great pains to restore and repair much of furniture dating from the Lauderdale's time and this has helped preserve many original features to the present day.

Of their sixteen children only seven lived to maturity. Three of the five sons died in the pursuit of their naval careers. The Countess died in 1755 aged 45 and the Earl in 1770 aged 73. He was survived by Lionel, Lord Huntingtower, Wilbraham, and three daughters Jane, Louisa and Frances.[7]

Lionel Tollemache, 5th Earl of Dysart

Lionel Tollemache, 5th Earl of Dysart succeeded to the title on his father's death. Despite spending on the house, the 4th Earl had kept his own son short of money during his lifetime and he had consequently married without his father's consent. His wife, Charlotte, was the youngest illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole, second son of Robert Walpole and niece of Horace Walpole who lived near to Ham across the Thames at Strawberry Hill. The 5th Earl refused to allow any change or renovation to Ham House or Helmingham Hall. By contrast he had two other properties in Northamptonshire and Cheshire completely destroyed. Charlotte died, childless, in 1789 and although Lionel remarried he remained without an heir. When this became apparent, the families of his surviving sisters, Louisa and Jane, reverted to the family name of Tollemache in anticipation of potential succession. On his death in 1799 his brother, Wilbraham became the 6th Earl of Dysart.[7]

Wilbraham Tollemache, 6th Earl of Dysart

Wilbraham was aged 60 when he inherited the title. One of his first acts was to buy the rights of the Manor of Kingston/Canbury from George Hardinge, extending the Dysarts' property south into Kingston. He had the wall that separated Ham House from the river demolished and replaced by a ha-ha, leaving the gates free-standing. Coade stone pineapples were added to decorate the balustrades and John Bacon's iconic statue of the river god, pictured here, also in Coade stone, dates from this period. Several busts of Roman emperors were relocated from the demolished walls to niches cut into the front of the house. Further restoration of the old furniture also took place as well as addition of Jacobean reproductions. The Dysarts also became patrons of John Constable at this time. Wilbraham's wife died in 1804 and, devastated, he moved away, close to the estate in Cheshire. Wilbraham died, childless, in 1821, aged 82.[7]

Louisa Tollemache, 7th Countess of Dysart

Of the 4th Earl's children, only the eldest daughter, Lady Louisa, by then widow of MP John Manners, still survived. Already heiress to Manners' 30,000 acres (12,000 ha; 47 sq mi) at Buckminster Park,[7] Louisa inherited the title and estates at Ham at the age of 76.[7] The remaining Tollemache estates were bequeathed to the heirs of Lady Jane.[9] Louisa continued the patronage of John Constable who was a frequent and welcome visitor to Ham. Increasingly infirm and blind in old age, Louisa lived to the age of 95, dying in 1840.[7]

Lionel Tollemache, 8th Earl of Dysart

Louisa's eldest son, William, had predeceased her in 1833. His eldest son, Lionel William John Tollemache, inherited the title and became the 8th Earl of Dysart. Lionel preferred to live in London and invited his brothers, Frederick and Algernon Gray Tollemache, to manage the estates and Ham and Buckminster. Lionel became increasingly reclusive and eccentric. Lionel's only son, William, a controversial figure, amassed great debts guaranteed by the expectation of inheriting the family fortune, however, he, too, predeceased his father who subsequently bequeathed the estates to his grandson, William John Manners Tollemache, with his brothers, Frederick and Algernon with Charles Hanbury-Tracy acting as trustees for 21 years to 1899. Following the 8th Earl's death in 1878, his son's creditors brought an action in the High Court against the Tollemache family who had to pay a sum of £70,000 to avoid forfeiting much of the Ham estate.

William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart

In his autobiography, Augustus Hare recounts a visit to Ham House in 1879 describing the dilapidation and disrepair contrasting with the evident treasures the house still contained. However, shortly after the 8th Earl's death, the 9th Earl, with agreement from the trustees, undertook extensive renovation of the house and its contents and, by 1885 it was fit to host social activities again, notably a garden party to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887. In 1890 Ada Sudeley published her 570 page book Ham House, Belonging to the Earl of Dysart.[16]

On 23 September 1899, full control of the Tollemache estates at Ham and Buckminster was transferred from trustees to 9th Earl, William John Manners Tollemache, then aged about 40, in accordance with his grandfather's will.

By the early 1900s the Dysarts had installed electricity and central heating at the house along with other modern gadgets including, in the Duchess's basement bathroom, a bath with jets and even a wave machine.

The 9th Earl travelled widely, rode despite blindness, invested successfully in the stock market and whilst eccentric and difficult, nonetheless was hospitable and supportive of the local community. His cantankerous nature proved too much for his wife who left him in the early 1900s but he lived on with other family members at Ham for many years. In the 1920s and 1930s he employed a staff of up to 20 including a chauffeur for his four cars including a Lanchester and Rolls Royce. When he died in 1935 he left investments worth £4,800,000 but had no direct heir. He was the last Earl of Dysart to live at the house.

Lyonel Tollemache, 4th Baronet of Hanby Hall

The inheritance passed to the Earl's elder sisters' families. His niece, Wynefrede, daughter of his sister Agnes, inherited the earldom. Wynefrede's cousin, Lyonell, at the age of 81, inherited the baronetcy and the estates at Ham and Buckminster. He and his middle-aged son, Cecil Lyonel Newcomen Tollemache lived at the house, but the lack of available staff during the war added to the difficulty of maintaining it. The nearby aircraft factory was a target for bombing raids and the house and grounds suffered some minor damage. Many of the house's contents were removed to the country for safety.[7] Most of the family papers were deposited in Chancery Lane but, whilst they survived the Blitz, they suffered significant water damage from fire hoses. Thought for some time to have been lost, many papers were subsequently recovered from the Ham House stables in 1953, though many were in poor condition as a result.[9]

National Trust

In 1943, Sir Lyonel invited the National Trust's first Historic Buildings Secretary, James Lees-Milne, to visit the house. Lees-Milne recorded both the melancholy state of the house and grounds but, even though it was devoid of its contents, he could immediately see the splendour of the underlying building and grounds. In 1948, Sir Lyonell and his son donated the house and its grounds to the Trust. The stables and other outlying buildings were sold privately and much of the remaining estate sold at auction in 1949.[7]

The National Trust at first transferred ownership of Ham House to the state on a long lease to the Ministry of Works. The contents of the house were purchased by the government who entrusted them to the Victoria and Albert Museum. By 1950, the house was open to the public and a series of research and restoration works since undertaken, restoring and reproducing much of the house's former splendour. The government relinquished its lease in 1990, and the compensation was used to form a fund to help contribute towards maintenance.[17]

Garden and grounds

The formal listed avenues leading to the house from the A307 are formed by more than 250 trees stretching east from the house to the arched gate house at Petersham, and south across the open expanse of Ham Common where it is flanked by a pair of more modest gatehouses. A third avenue to the west of the house no longer exists, whilst the view to and from the Thames completes the principal approaches to the house.

From the initial survey drawings produced by Robert Smythson and son in 1609[18] it is clear that the garden design was considered as important as that of the house and that the two were intended to be in harmony.[1] The original design shows the house set within a range of walled gardens, each with different formal designs, as well as an orchard and vegetable garden. However, uncertainty remains as to how much of the original design was actually realised.[19] Nevertheless, the plans illustrate the influence of French garden design of the time, with its emphasis on visual effects and perspectives.[20]

_(attributed_to)_-_Ham_House_from_the_South_(around_1675%E2%80%931679)_-_1139878_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

The 1671 plans for the renovation undertaken by the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale, which have been attributed to John Slezer and Jan Wyck, demonstrate the continued importance of the garden design, with many features that can be experienced today such as the Orangery, the Cherry Garden, the Wilderness and eight grass squares (plats) on the south side of the house.[19] Both the private apartments for the Duke and Duchess and the State Apartments added to the South Front of the house were designed to overlook the formal gardens, an innovation that was highly commended by contemporaries.[1] John Evelyn remarked favourably on the garden design observed during his 1678 visit, noting “...the Parterres, Flower Gardens, Orangeries, Growves, Avenues, Courts, Statues, Perspectives, Fountaines, Aviaries…”.[21] The Duchess also commissioned a set of iron gates for the north entrance to the property, which remain in place today.[1]

The 3rd and 4th Earls of Dysart who subsequently inherited the estate maintained the formal garden features into the 18th century, while also planting avenues of trees in the wider vicinity.[19] After inheriting the estate in 1799, the 6th Earl opened the north front of the property to the river and installed the Coade stone statue of the River God at the front of the house.[1] He also created the sunken ha-ha which runs along the north entrance of the property.[1] Louisa Manners, 7th Countess of Dysart, inherited the estate upon her brother’s death and was acquainted with the artist John Constable, who completed a sketch of Ham House from the south gardens during a visit in 1835.[1]

By 1972, the gardens had become significantly overgrown – large bay trees at the front blocked the view of the busts in their niches, the south lawn had reverted to a single large expanse of grass and the Wilderness was overgrown with rhododendrons and sycamore trees.[22] Work to restore the 17th century design to the eastern and southern parts of the garden began in 1975.[19] In 1979, an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum entitled "The Garden" included a model of Ham House with its gardens shown according to the 1672 plans.[23] This model illustrated the details of the 17th-century design in terms of both layout and plant selection.[23] By 1977, the grass plats and the structure of the Wilderness to the south of the house were re-established.[23] The 1675 painting by Henry Danckaerts showing the Duke and Duchess in the south gardens was used to guide the restoration of the furniture and statues now in place.[23]

In approaching the restoration of the “cherry garden” on the east side of the house, there was less documentary evidence available to guide the design.[23] A set of diagonally-set parterres outlined by box hedges and cones were planted with lavender, with the whole garden being enclosed by tunnel arbours and double yew hedges.[23] However, later archaeological studies completed in the 1980s indicated no evidence of formal gardens in this area prior to the 20th century.[23] Despite this finding, the National Trust’s Gardens Panel decided not to remove the garden, but rather allow it to remain so long as visitors to the property were clearly informed of its origins.[23]

The focus of garden restoration since 2000 has been the walled garden to the west of the house, to restore its use as a supply of fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers.[23] The produce is used in the Orangery cafe, while the flowers are used to decorate the house. The garden itself is also used as an exhibition space, with information about tulip varieties and the range of edible flowers.

In film and television

The property is a popular period location for film and television productions, on account of its 17th- and 18th- century architecture, interiors and gardens. The house has also featured in documentary TV and radio.[24][25]

Film

- Spice World (1997)

- The Young Victoria (2009) – The exterior was used as Kensington Palace.

- An Englishman in New York (2009)

- Never Let Me Go (2010) – The house was used as the setting for Hailsham Boarding School in the 2010 film Never Let Me Go, which starred Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield, and Keira Knightley.[26]

- Anna Karenina (2012) – Ham's interior provided the location for Vronsky's rooms in Joe Wright's 2012 film Anna Karenina.[27]

- John Carter (2012) – Ham House's interior featured in Disney's version of Burroughs' Martian adventure, John Carter.

- A Little Chaos (2014)

- Victoria and Abdul (2017)

- Downton Abbey (2019)

- The Last Vermeer (2019)

- Rebecca (2020)

Television

- Left, Right and Centre (1959)

- Steptoe and Son (1964) – The BBC comedy series Steptoe and Son featured wintertime exterior shots in the episode "Fit For Heroes" (1964).

- Cambridge Spies (2003)

- Ballet Shoes (2007)

- Sense and Sensibility (2008)

- Broadside (2009)

- Downton Abbey (2010–2015)

- The Scandalous Lady W (2015)

- Taboo (2017)

- Bodyguard (2018)

- A Stitch in Time (2018–2019)

- Belgravia (2020)

- The Great (2020)

- George Clarke's National Trust Unlocked (2020)

- Taskmaster (Trailer for Channel 4 series) (2020)

Access

The house can be reached by public transport, being in Transport for London travel zone 4; from Richmond station (London) the 65 bus service serves Petersham Road and the 371 bus service serves Sandy Lane. These routes terminate near Kingston station.

There is a car park north-west of the house, next to the Thames. Hammerton's Ferry, to the north-east, links to a playground between Orleans House Gallery and Marble Hill House below Twickenham's central embankment. The house is accessible to pedestrians and cyclists via Thames Path national trail.

References

- Rowell, Christopher, ed. (2013). Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- "Ham House and Garden". National Trust. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Historic England (10 January 1950). "Ham House (1080832)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Historic England (1 October 1987). "Ham House (1000282)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Malden, H E, ed. (1911). "Kingston-upon-Thames: Manors, churches and charities". A History of the County of Surrey. 3. pp. 501–516.

- Beddard, Robert (January 1995). "Ham House". History Today. 45 (1). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Pritchard 2007.

- Gilbert, Christopher; Thornton, Peter (1980). "The Furnishing and Decoration of Ham House". Furniture History. 16.

- "Estates of the Tollemache Family of Ham House in Kingston upon Thames, Ham, Petersham and elsewhere: Records, 14th cent-1945". Surrey History Centre. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Parliamentary Committee Document CMS1140464. Ham House NT.

- "Mr. Murray's Sequestration stayed". Journal of the House of Lords: 1644. Institute of Historical Research. 14 June 1645.

- "Order to free Mr. Murray's Estate from Sequestration". Journal of the House of Lords (1645–1647). Institute of Historical Research. 18 April 1646.

- "Elizabeth Murray". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19601. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Surrey History Centre, ref 59/2/4/1, cited in Pritchard 2007, p.12.

- Murdoch, Alexander (2004). "Campbell, John, second duke of Argyll and duke of Greenwich (1680–1743)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4513.

- Baroness Ada Hanbury-Tracy Sudeley (1890). Ham House, Belonging to the Earl of Dysart.

- Bradley, Victoria (2007). "Ham House to the Present Day". In Pritchard, Evelyn (ed.). Ham House and its owners through five centuries 1610–2006. London: Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 9781955071727.

- "Plan of Ham House and Gardens by Robert Smythson, c. 1609". British Architectural Library, RIBA. no. 12941. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ham House, Surrey. Swindon: The National Trust. 2009.

- Anthony, John (1991). The Renaissance Garden in Britain. Shire Publications Ltd.

- Evelyn, John (1870). Memoirs. G. P. Putnam & sons.

- Thomas, Graham Stuart (1979). Gardens of the National Trust. Book Club Associates.

- Sales, John (2018). Shades of Green: My Life as the National Trust's Head of Gardens. London: Unicorn.

- "How Elizabeth Dysart Transformed Ham House". Harlots, Housewives and Heroines: A 17th Century History for Girls. BBC Four. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "Cleaning stately homes: Ham House". Woman's Hour. 25 April 2006. BBC. Radio 4. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Behind the scenes at Richmond's Ham House". BBC News. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Williams, Sally (7 September 2012). "Anna Karenina: back from the brink". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

Further reading

- Edwards, Ralph; Ward-Jackson, Peter (1959). Ham House A Guide (fourth ed.). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO).

- Pritchard, Evelyn (2007). Ham House and its owners through five centuries 1610–2006. London: Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 9781955071727.

- Rowell, Christopher, ed. (2013). Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300185409.

- Thornton, Peter; Tomlin, Maurice (1981). The Furnishing and Decoration of Ham House. London: Furniture History Society.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ham House. |