Griqualand West

Griqualand West is an area of central South Africa with an area of 40,000 km2 that now forms part of the Northern Cape Province. It was inhabited by the Griqua people – a semi-nomadic, Afrikaans-speaking nation of mixed-race origin, who established several states outside the expanding frontier of the Cape Colony. It was also inhabited by the pre-existing Tswana and Khoisan peoples.

| Historical states in present-day South Africa |

|---|

|

|

|

In 1873 it was proclaimed as a British colony, with its capital at Kimberley, and in 1880 it was annexed by the Cape Colony. When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, Griqualand West was part of the Cape Province but continued to have its own "provincial" sports teams.

Early history

The indigenous population of the area were the Khoi-khoi and Bushmen peoples, who were hunter-gatherers or herders. Early on they were joined by the agriculturalist Batswana, who migrated into the area from the north. They comprised the majority of the population throughout the region's history, up until the present day. By the early 19th century the whole area came to be dominated by the powerful Griqua people, who gave the region its name.

Independent Griqua state

Origins of the Griqua people

The Griqua are a mixed people who originated in the intermarriages between Dutch colonists in the Cape and the Khoikhoi already living there. They turned into a semi-nomadic Afrikaans-speaking nation of horsemen who migrated out of the Cape Colony and established short-lived states on the Colony's borderlands, similar to the Cossack states of imperial Russia.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) did not intend the Cape Colony at the Southern tip of Africa to become a political entity. As it expanded and became more successful, its leaders did not worry about frontiers. The frontier of the colony was indeterminate and ebbed and flowed at the whim of individuals. While the VOC undoubtedly benefited from the trading and pastoral endeavours of the trekboers, it did little to control or support them in their quest for land. The high proportion of single Dutch men led to their taking indigenous women as wives and companions, and mixed-race children were born. They grew to be a sizeable population who spoke Dutch and were instrumental in developing the colony.

These children did not attain the social or legal status accorded their fathers, mostly because colonial laws recognised only Christian forms of marriage. This group became known as Basters, or bastards. The colonists, in their paramilitary response to insurgent resistance from Khoi and San people, readily conscripted the Basters into commandos. This ensured the men became skilled in lightly armed, mounted, skirmish tactics.

Griqua migrations

Equipped with guns and horses, many of the Basters who were recruited to war chose instead to abandon their paternal society and to strike out and live a semi-nomadic existence beyond the Cape's frontier. The resulting stream of disgruntled, Dutch-speaking, trained marksmen leaving the Cape hobbled the Dutch capability to crew their commandos. It also created belligerent, skilled groups of opportunists who harassed the indigenous populations the length of the Orange River. Once free of the colonies, these groups called themselves the Oorlam. In particular, the group led by Klaas Afrikaner became notorious. He attracted enough attention from the Dutch authorities to cause him to be rendered to the colony and banished to Robben Island in 1761.

One of the most influential of these Oorlam groups was the "Griqua". In the 19th century, the Griqua controlled several political entities which were governed by Kapteins or Kaptyns (Dutch for "Captain", i.e. leader) and their Councils, with their own written constitutions. The Griqua had also largely adopted the Afrikaans language before their migrations.

Adam Kok I, the first Kaptein of the Griqua and recognised by the British, was originally a slave who had bought his own freedom. He led his people north from the interior of the Cape Colony. Probably because of discrimination against his people, they again moved north—this time outside the Cape, taking over areas previously controlled by San and Tswana people. This area, where most of the Griqua nation settled, was near the Orange River, just west of the Orange Free State, and on the southern skirts of the Transvaal. It came to be called Griqualand West, and the territory was centered on its capital "Klaarwater", later renamed Griekwastad ("Griquatown").

Waterboer dynasty and Griqualand West

While much of the Griqua people now settled, many remained nomadic, and Adam Kok's people later split into several semi-nomadic nations. After a significant schism, a portion of the Griqua nation migrated to the south-east under the leadership of Adam Kok's son Adam Kok II (to the south-east they were later to found Philippolis and then Griqualand East.[1]

In the original area, which now came to be called Griqualand West, Andries Waterboer took over control and founded the powerful Waterboer dynasty. The Waterboer Kapteins ruled the region until the influx of Europeans accompanying the discovery of diamonds, and to some degree afterwards too. In 1834, the Cape Colony recognized Waterboer's rights to his land and people. It signed a treaty with him to ensure payment for the use of the land for mining. In both Griqualands, East and West, the Griqua were demographically outnumbered by the pre-existing Bantu people and, in some areas, by European settlers, and thus the two Griqualands maintained their Griqua identity only through political control.

Diamond fields and land disputes

_Adamantia_p358.jpg.webp)

In the years 1870–1871 a large number of diggers moved into Griqualand West and settled on the diamond fields near the junction of the Vaal and Orange rivers. This was land through which the Griqua regularly moved with their herds and it was additionally situated in part on land claimed by both the Griqua chief Nicholas Waterboer and by the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State.

In 1870, Transvaal President Marthinus Wessel Pretorius declared the diamond fields as Boer property and established a temporary government over the diamond fields. The administration of this body was not satisfactory to the Boers, the diggers, the Griqua or the indigenous Tswana. Tension rapidly grew between these parties until Stafford Parker, a former British sailor, organised a faction of the diggers to drive all of the Transvaal officials out of the area.

Diggers Republic (1870–71)

At the settlement of Klipdrift, on 30 July 1870 Stafford Parker declared the independent Klipdrift Republic (also known as the Digger's Republic and the Republic of Griqualand West) and was also chosen as president. Klipdrift was promptly renamed "Parkerton" after the new president, who began to collect taxes (often at gunpoint). Factions in the Republic also implored the British Empire to impose its authority and annex the territory.

By December of the same year about 10 000 British settlers made their home in the new republic. The republic sat next to the Vaal River, but existed for an extremely short time. During the following year, Boer forces unsuccessfully attempted to regain the territory through negotiation. British Governor Sir Henry Barkly was asked to mediate. Barkly set up the Keate Committee to hear evidence and, in the famous "Keate Award", ruled against the Boer Republics and in favour of Nicholas Waterboer.

Direct British rule (1871–1880)

At this juncture, Waterboer offered to place the territory under the administration of Queen Victoria. The offer was accepted, and on 27 October 1871 the district, together with some adjacent territory to which the Transvaal had laid claim, was proclaimed (under the name of Griqualand West Colony) British territory.[2][3][4]

Further territorial disputes

Territorial disputes continued, even after the British annexation. When the annexation had taken place, a party in the Orange Free State volksraad had wished to go to war with Britain but the wiser counsels of its president prevailed. The Orange Free State did not abandon its claims, believing that the diamond fields were the means of restoring the credit and prosperity of the Free State. Griqualand West was not financially viable, and carried with it enormous public debt. The matter continued for a considerable time and caused immense tension in southern Africa.

In the face of claims from the Orange Free State and the Griqua authorities, the Griqualand West Land Court was established in 1875, under Justice Andries Stockenström. Waterboer's claims to the diamond fields, strongly presented by his agent David Arnot, were based on the treaty concluded by his father with the British in 1834 and on various arrangements with the Kok chiefs; the Orange Free State based its claim on its purchase of Adam Kok's sovereign rights and on long occupation. The difference between proprietorship and sovereignty was confused or ignored. That Waterboer exercised no authority in the disputed district was admitted. In a crucial finding Stockenström ruled that, as the Griqua people were nomadic, the Griqua chiefs (or "captains") were rulers over a people, but not over a fixed territory. The Griqua people had also only arrived in this part of southern Africa a little over 50 years before, in the early nineteenth century. The Griqua captains therefore did not automatically get the right to own & develop all of the land through which they moved, but only those areas in which they would settle. Other areas they could continue to move through, but were not given automatic title to own and develop. This resulted in the denial of many of the titles issued by the powerful Griqua Captain Nicolaas Waterboer, outside of his core areas around Griquatown and Albania, were also denied. It also effectively ruled in favour of the Orange Free State. A furore resulted, as accusations were leveled that Stockenström was biased, and sympathetic towards the Orange Free State President Johannes Brand.

A form of resolution eventually came about in July 1876, when Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon, at that time secretary of state for the colonies, granted the Free State payment "in full satisfaction of all claims which it considers it may possess to Griqualand West."[5]

In the opinion of Dr Theal, who has written the history of the Boer Republics and has been a consistent supporter of the Boers, the annexation of Griqualand West was probably in the best interests of the Orange Free State. "There was," he states, "no alternative from British sovereignty other than an independent diamond field republic." At this time, largely owing to the exhausting struggle with the Basutos, the Free State Boers, like their Transvaal Republic neighbours, had drifted into financial straits. A paper currency had been instituted, and the notes, known as "bluebacks", soon dropped to less than half their nominal value. Commerce was largely carried on by barter, and many cases of bankruptcy occurred in the state. But as British annexation in 1877 saved the Transvaal from bankruptcy, so did the influx of British and other immigrants to the diamond fields, in the early 1870s, restore public credit and individual prosperity to the Boers of the Free State. The diamond fields offered a ready market for stock and other agricultural produce. Money flowed into the pockets of the farmers. Public credit was restored. " Bluebacks " recovered par value, and were called in and redeemed by the government. Valuable diamond mines were also discovered within the Orange Free State, of which the one at Jagersfontein is the richest. Capital from Kimberley and London was soon provided with which to work them.

Pressure on the Cape Colony to annex the territory

After annexing Griqualand West, the British initially attempted to incorporate it into the Cape Colony, and put significant pressure on the Cape Government to annex it. The new Prime Minister of the Cape, John Molteno refused, citing the enormous public debt of the territory, as well as objections from portions of the indigenous and settler communities of Griqualand.

Local control continued to pass increasingly from the Griqua kaptijns into the hands of the growing digger community of the diamond fields. The prospect of complete dis-empowerment in a "Diamond Fields Republic" became a significant concern of the remaining Griqua.

Under pressure, the embattled Griqua leader Nicolaas Waterboer send a formal request to the Cape Government to request incorporation; a request that coincided with renewed pressure on the Cape Government to agree to the union.[6]

Union with Cape Colony (1880)

.svg.png.webp)

On being presented with a request from Nicholas Waterboer for union with the Cape Colony, there had begun a protracted debate over whether Griqualand West should be joined to the Cape in a confederation, or whether it should be annexed to the Cape Colony in a total union. The former view was supported by Lord Carnarvon and the British Colonial Office in London – as a first step to bringing all of southern Africa into a British-ruled confederation.[7] The latter view was put forward by the Cape Parliament, particularly by its strong-willed Prime Minister John Molteno, who had initially opposed any form of union with the unstable and heavily indebted territory, and now demanded evidence from Britain that the local population would be consulted in the process.[8] Suspicious of British motives, in 1876 he travelled to London as plenipotentiary to make the case that union was the only viable way that the Cape could administer the divided and underdeveloped territory, and that a lop-sided confederation would be neither economically viable, nor politically stable. In short, Griqualand West should either be united with the Cape, or kept totally independent from it. After striking a deal with the Home Government and receiving assurances that local objections had been appeased, he passed the Griqualand West Annexation Act on 27 July 1877.[9]

The act specified that Griqualand West would have the right to elect four representatives to the Cape parliament, two for Kimberley and two for the Barkly West region. This number was doubled in 1882 (Act 39 of 1882). The Cape Government also enforced its non-racial system of Cape Qualified Franchise. This meant that all resident males could qualify for the vote, with the property-ownership qualifications for suffrage applied equally, regardless of race. This was welcomed by the Griqua, but rejected by the recently arrived diggers of the Kimberley diamond fields.[10] In the judiciary, the local Griqua attorney-general reported to the Cape Supreme Court, which got concurrent jurisdiction with the High Court of Griqualand West in the territory.[11]

The implementation of the act was set for 18 October 1880, when Griqualand West was formally united with the Cape Colony, followed soon afterwards by Griqualand East. [12]

Current

Today, Basters are a separate ethnic group of similarly mixed origins living in south-central Namibia; Northern Cape at Campbell and Griquatown; (the historic territory of Griqualand West); the Western Cape (around the small le Fleur Griqua settlement at Kranshoek); and at Kokstad.

The total Griqua population is unknown. The people were submerged by several factors. The most important factor were the racist policies of the Apartheid era, during which many of the Griqua people took on the mantle of "Coloured" fearing that their Griqua roots might place them at a lower level with the Africans.

Genetic evidence indicates that the majority of the present Griqua population is descended from European, Khoikhoi and Tswana ancestors, with a small percentage of Bushman ancestry.[13]

Rulers and administrators of the territory

Independent Griqua Kaptyns (1800–1871)

- Adam Kok I (1800–1820)

(1820 split in the Griqua nation)

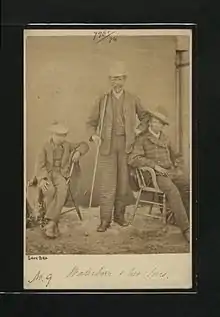

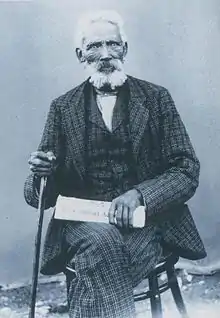

- Andries Waterboer (1820–1852)

- Nicolaas Waterboer (1852–1896)

(Continuation of dynasty in symbolic role until present day)

British imperial rule (1871–1880)[14]

- Commissioner Joseph Millerd Orpen (27 October 1871 – 10 January 1873)

- Administrator and then Lieutenant Governor Richard Southey (10 January 1873 – 3 August 1875)

- Lieutenant Governor William Owen Lanyon (3 August 1875 – March 1879)

- Lieutenant Governor James Rose Innes (March 1879 – 15 October 1880)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Griqualand West. |

See also

References

- Jeroen G. Zandberg. 2005. Rehoboth Griqua Atlas. ISBN 90-808768-2-8.

- "'The rock on which the future will be built' | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Roberts, Brian (1976). Kimberley: Turbulent City – Brian Roberts – Google Books. ISBN 9780949968623. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- "The Republic of Klipdrift is proclaimed | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Theal G.: History of South Africa from 1873 to 1884, Twelve eventful Years. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1919.

- "Griqua | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Illustrated History of South Africa. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 1992. ISBN 0-947008-90-X. p.182, "Confederation from the Barrel of a Gun"

- M. Mbenga: New History of South Africa. Tafelberg, South Africa. 2007.

- Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip, p. 155.

- L Waldman: The Griqua Conundrum: Political and Socio-Cultural Identity in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Oxford. 2007.

- Northern Cape High Court Kimberley] by Lizanne van Niekerk, Northern Cape Bar

- Lipschutz, Mark R.; Kent Rasmussen, R. (1989). African Historical Biographies. ISBN 9780520066113.

- Nigel Penn. 2005. The Forgotten Frontier. ISBN 0-8214-1682-0.

- "The British Empire, Imperialism, Colonialism, Colonies". www.britishempire.co.uk.

.svg.png.webp)