Great Council of Venice

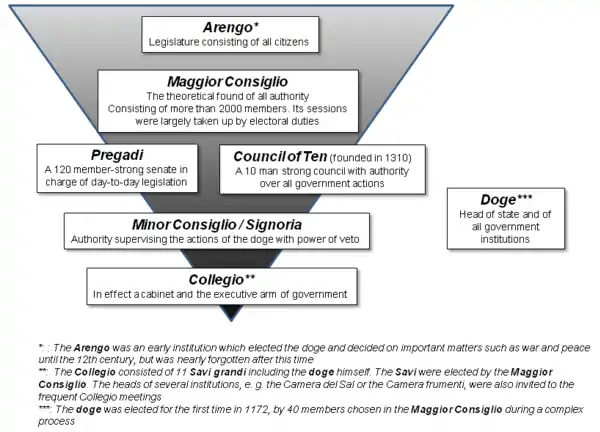

The Great Council of Venice[1] or Major Council (Italian: Maggior Consiglio; Venetian: Mazor Consegio), originally the Consilium Sapientium (Latin for "Council of Wise Men"), was a political organ of the Republic of Venice between 1172 and 1797 and met in a special large hall of the Palazzo Ducale. Participation in the Great Council was established on hereditary right, exclusive to the patrician families enrolled in the Golden Book of the Venetian nobility.

The Great Council was unique at the time in its usage of lottery to select nominators for proposal of candidates, who were thereafter voted upon.[2] The Great Council had the power to create laws and elected the Council of Ten.

History

In 1143 the Consilium Sapientium was formally established as a permanent representation of the sovereign Concio (or assembly) of freemen (citizens and patricians). The Act formalized the set-up in communal form of the State, with the birth of the Commune Veneciarum ("City of Venice"). Thirty years later (1172) the Consilium was transformed into sovereign assembly known as the Great Council. The council initially consisted of 35 councilors, but gradually expanded to over 100.

Part of it was the Council of the Forty - whose members belonged to it by law - which served effectively as a Supreme Court or highest of constitutional bodies. The Council of Forty was established around the year 1179.

The Serrata of the Great Council

Proposals for participation in the transformation of the hereditary right to counsel or co-opted by the board itself had already been presented and rejected several times under dogado of Giovanni Dandolo, in 1286.

However, under Doge Pietro Gradenigo the nobility insisted that to ensure more stability and continuity of participation in the Government of the Republic, new laws needed to be enacted. This was brought together on 28 February 1297, an event known as the Serrata (Lock-out). This provision of law opened the Great Council only to those who already had been part of the preceding four years,[3] and every year, forty raffled among their descendants. The reform also removed time limits on how long a person could be a member of the Council and the number of members increased to more than one 1,100.[4]

The entry of new members was further limited by additional laws in 1307 and 1316. On 19 July 1315, a book of Italian nobilities was established. Only those listed in the book and above 18 years of age were eligible for the position in the Major Council.

In 1423 the Great Council formally abolished the concio.

From the sixteenth century to the fall of the Republic

In 1506 and 1526, records were established in order to determine births and marriages to facilitate the detection of the right of access to the body of nobility. In 1527 the members of the Greater Council chose to grant equal rights to members of the council for all men over twenty years of the most illustrious families of the city. At this point, the council reached its maximum size of 2746 members.[5]

The effect of the provisions of the Serrata had increased dramatically the number of members. In the sixteenth century, it was common for up to 2095 patricians to have the right to sit in the Ducal Palace. There was an obvious difficulty in managing such a body. This led to a delegation of more immediate functions of government bodies to smaller, leaner and selected bodies, in particular the Senate.

In some rare cases, facing severe economic difficulties and dangers, access to the Great Council was open to new families. By means of lavish gifts to the state, this was the case at the time of the War of Chioggia and the War of Candia, when, to support the enormous cost of the wars, new wealthy families were admitted.

Another peculiarity was the creation over time of a division within the nobility itself, that is, families who were able in time to keep intact or to increase their economic capacity, and the poor ones (the so-called Barnabites). The latter may have gradually or suddenly lost their wealth, but continued to maintain the hereditary right to sit in the Great Council. This often took the two sides of the nobility to clash in council and opened the possibility to cases of vote buying.

It was the Great Council, on 12 May 1797, that declared the end of the Republic of Venice, by deciding - upon the Napoleonic invasion - to accept the abdication of the last Doge Ludovico Manin and dissolve the aristocratic assembly: despite lacking the required quorum of 600 members, the board voted overwhelmingly (512 votes in favor, 30 against, 5 abstentions) the end of the Venetian Republic and the transfer of powers to an indefinite provisional government.

Gallery

Behind the Doge’s throne, is occupied by the longest canvas painting in the world, Il Paradiso of Tintoretto

Behind the Doge’s throne, is occupied by the longest canvas painting in the world, Il Paradiso of Tintoretto.jpg.webp)

See also

Notes

The first volume of Annali Veneti e del Mondo written by Stefano Magno describes the origins of the Venetian noble families and presents the alphabetically arranged list with dates of their admission to Great Council.[6]

References

- Lane, Frederic (1973). Venice, a maritime republic. JHU Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8018-1460-0.

- Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-521-45891-9.

- Frederic C. Lane Venice. A Maritime Republic, Chapter IX, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. (Italian translation: "Storia di Venezia", Edizioni Einaudi, 1978, Torino, pag. 133: "stabilendo che tutti coloro che ne erano membri, o lo erano stati negli ultimi quattro anni, avrebbero continuato da allora in poi a farne parte se approvati con almeno dodici voti dal Consiglio della Quarantia."

- Frederic C. Lane Venice. A Maritime Republic, The Johns Hopkins University Press 1973, (Italian translation: "Storia di Venezia", Edizioni Einaudi, 1978, Torino, pag.133: "La riforma...provvide eliminando ogni limite alle dimensioni del consiglio stesso". (...) "I membri del Consiglio furono più che raddoppiati, salendo a oltre 1.100".

- Alessandra Fregolent, Giorgione, Electa, Milano 2001, pag. 11. ISBN 88-8310-184-7

- The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, four volumes, American Philosophical Society, 1976–1984, p. 329, ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9