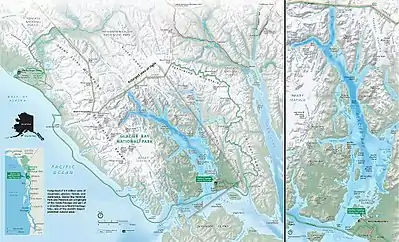

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve is an American national park located in Southeast Alaska west of Juneau. President Calvin Coolidge proclaimed the area around Glacier Bay a national monument under the Antiquities Act on February 25, 1925.[4] Subsequent to an expansion of the monument by President Jimmy Carter in 1978, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) enlarged the national monument by 523,000 acres (817.2 sq mi; 2,116.5 km2) on December 2, 1980, and created Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve.[5] The national preserve encompasses 58,406 acres (91.3 sq mi; 236.4 km2) of public land to the immediate northwest of the park, protecting a portion of the Alsek River with its fish and wildlife habitats, while allowing sport hunting.

| Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape)[1] | |

Johns Hopkins Glacier | |

Location in Alaska  Location in North America | |

| Location | Hoonah-Angoon Census Area and Yakutat City and Borough, Alaska, United States |

| Nearest city | Juneau |

| Coordinates | 58°30′N 137°00′W |

| Area | 3,223,384 acres (13,044.57 km2)[2] |

| Established | December 2, 1980 |

| Visitors | 597,915 (in 2018)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve |

| Part of | Kluane / Wrangell–St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) |

| Reference | 72ter |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Extensions | 1992, 1994 |

Glacier Bay became part of a binational UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979, and was inscribed as a Biosphere Reserve in 1986. The National Park Service undertook an obligation to work with Hoonah and Yakutat Tlingit Native American organizations in the management of the protected area in 1994.[6] The park and preserve cover a total of 3,223,384 acres (5,037 sq mi; 13,045 km2), with 2,770,000 acres (4,328 sq mi; 11,210 km2) being designated as a wilderness area.[7]

Geology

The west side of the bay consists of a 26,000 feet thick sequence of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, mainly massive limestones and argillite. The oldest rocks in this sequence are the Late Silurian Willoughby limestone and the youngest being the Middle Devonian Black Cap limestone. An outcrop west of Tidal Inlet includes a sandstone, graywacke and limestone of unknown age. Sedimentary rocks of unknown age on the east side of Muir Inlet include tuff interbedded with limestone. The rocks exposed on the 1,205 foot high hill called "The Nunatak" have been metamorphosed. Early Cretaceous diorite stocks are exposed south of Tidal Inlet, and on Sebree and Sturgress Islands. Quartz diorite outcrops on Lemesurier Island. A granitic stock is exposed in Dundas Bay. Mafic dikes up to 20 feet in width occur throughout the area.[8]

Glacial advances occurred 7,000, 5,000 and 500 years ago, with the last extending to the entrance of the bay, where it left a huge semicircular terminal moraine. The consequent surface glacial deposits include gravels as outwash and moraines. Glacial gravels extend up to 2000 feet up the mountain slopes. Lakes have formed where the glaciers have dammed the heads of valleys. Preglacial forests are found east of Goose Cove and on the east side of Muir Inlet. According to Rossman, "One of the outstanding features of the Glacier Bay area is the rapid advance and retreat of the glaciers during several substages within the last few thousand years."[8]:K27-K28,K46

A molybdenite deposit occurs on The Nunatak in quartz veins associated with a quartz monzonite porphyry,[9][10] which includes gold at 0.04 ounces per ton, and silver at 7.07 ounces per ton. A copper deposit occurs on Observation Mountain. Quartz veins containing gold are exposed west of Dundas Bay and on Gilbert Island. Placer gold is also found in the bay. A silver deposit was mined on the western portion of Rendu Inlet.[8]:K49-K50

According to MacKevett et al., "The most extensive and best gold placer deposits...are in the beach sands near Lituya Bay." Mining of these sands started in 1894, employing up to 200 men by 1896. However, most production had ended by 1917.[11]

The granodiorite and quartz diorite area between Lamplugh Glacier and Reid Glacier contains most of the quartz vein gold lodes, which were produced by six mines. This is known as the Reid Inlet gold area. The Monarch Mines and the Incas Mine was discovered in 1924 by J. Ibach. The Monarch No. 1 and No. 2 veins were drift mined with 200 and 150 foot adits respectively. The LeRoy Mine was the largest though, discovered in 1938 by Gustavus founder and resident A.L. Parker and his son L.F. Parker. They operated a two-stamp mill and an aerial tramway. Most production had ceased by 1945 though.[11][12]

The region experiences tectonic activity with frequent earthquakes. Earthquake-induced landslides have been significant forces for change, inducing tsunamis.[13] Additionally, parts of the region are undergoing post-glacial rebound (also known as isostatic rebound), the process in which land rises after the weight of the glacier has been removed.[14]

Geography

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve occupies the northernmost section of the southeastern Alaska coastline, between the Gulf of Alaska and Canada. The Canada–US border approaches to within 15 miles (24 km) of the ocean in the St. Elias Mountains at Mount Fairweather, the park's tallest peak at 15,300 feet (4,700 m), transitioning to the Fairweather Range from there southwards. The Brady Icefield caps the Fairweather Range on a peninsula extending from the ocean to Glacier Bay, which extends from Icy Strait to the Canada–US border at Grand Pacific Glacier, cutting off the western part of the park. To the east of Glacier Bay the Takhinsha Mountains and the Chilkat Range form a peninsula bounded by the Lynn Canal on the east, with the park's eastern boundary with Tongass National Forest running along the ridgeline. The park's northwestern boundary, which also abuts Tongass National Forest, runs in the valley of the Alsek River to Dry Bay. The preserve lands comprise a small area at Dry Bay — the majority of Glacier Bay lands are national park lands. The park boundary excludes Gustavus at the mouth of Glacier Bay. The lands adjoining the park to the north in Canada are included in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park.[15]

No roads lead to the park and it is most easily reached by air travel. During some summers there are ferries to the small community of Gustavus or directly to the marina at Bartlett Cove.[16] Despite the lack of roads, the park received an average of about 470,000 recreational visitors annually from 2007 to 2016, with 520,171 visitors in 2016.[3] Most of the visitors arrive via cruise ships. The number of ships that may arrive each day is limited by regulation.[16] Other travelers come on white-water rafting trips, putting in on the Tatshenshini River at Dalton Post in the Yukon Territory and taking out at the Dry Bay Ranger Station in the Glacier Bay National Preserve.[17] Trips generally take six days and pass through Kluane National Park and Reserve in the Yukon and Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in British Columbia.[17]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Glacier Bay National Park has six climate zones; Subarctic With Cool Summers and Year Around Rainfall (Dfc), Subpolar Oceanic (Cfc), Temperate Oceanic (Cfb), Humid Continental Mild Summer Wet All Year (Dfb), Humid Continental Dry Cool Summer (Dsb), and Warm Summer Mediterranean (Csb). The plant hardiness zone at Glacier Bay Visitor Center is 7a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of 4.2 °F (-15.4 °C).[18]

| Climate data for Glacier Bay, Alaska, 1966–2015 Summary | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.6 (−0.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

38.1 (3.4) |

46.2 (7.9) |

53.7 (12.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

62.5 (16.9) |

61.0 (16.1) |

54.4 (12.4) |

46.2 (7.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

33.9 (1.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 27.4 (−2.6) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

32.9 (0.5) |

39.3 (4.1) |

46.0 (7.8) |

52.1 (11.2) |

54.9 (12.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

48.5 (9.2) |

41.5 (5.3) |

33.6 (0.9) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 23.2 (−4.9) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

32.3 (0.2) |

38.3 (3.5) |

43.8 (6.6) |

47.2 (8.4) |

46.8 (8.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

36.7 (2.6) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

34.9 (1.6) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.36 (162) |

4.75 (121) |

3.74 (95) |

2.91 (74) |

3.66 (93) |

2.76 (70) |

4.13 (105) |

6.00 (152) |

9.96 (253) |

11.19 (284) |

7.81 (198) |

7.30 (185) |

70.57 (1,792) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 34.6 (88) |

22.9 (58) |

15.7 (40) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.3 (3.3) |

15.6 (40) |

23.8 (60) |

115.4 (293.1) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center [19] | |||||||||||||

Environment

Glacier Bay National Park preserves nearly 600,000 acres (2428.1 km2) of federally protected marine ecosystems in Alaska (including submerged lands) against which other less-protected marine ecosystems can be compared.[6] Within the park and preserve there are two Tlingit ancestral homelands that are of cultural and spiritual significance to living communities today.[6] The Alsek River serves as a route of discovery and migration from the coastal mountain range in the park to the Pacific Ocean in the preserve.[6] Within the preserve, in contrast to the park, the Alsek River provides a setting for subsistence uses, commercial fishing, and hunting as provided for in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) while simultaneously protecting the glacial ecosystem.[6]

Glaciers

The Park is named for its abundant tidewater and terrestrial glaciers, numbering 1,045 in total.[20]

There are seven tidewater glaciers in the park: Margerie Glacier, Grand Pacific Glacier, McBride Glacier, Lamplugh Glacier, Johns Hopkins Glacier, Gilman Glacier, and LaPerouse Glacier.[21] (High tide-water glaciers also include Riggs Glacier, Reid Glacier, Lituya Glacier, and North Crillon Glacier.[22]) Four of these glaciers actively calve icebergs into the bay. In the 1990s, the Muir Glacier receded to the point that it was no longer a tidewater glacier. The advance and recession of the park's glaciers has been extensively documented since La Perouse visited the bay in 1786. According to the U.S. National Park Service, "In general, tidewater and terrestrial glaciers in the Park have been thinning and slowly receding over the last several decades."[23] Some glaciers continue to advance, including Johns Hopkins Glacier and glaciers in Lituya Bay.

Glacial retreat

Joseph Whidbey, master of the Discovery during the 1791–95 Vancouver expedition, found Icy Strait, at the south end of Glacier Bay, choked with ice in 1794. Glacier Bay itself was almost entirely covered by one large tidewater glacier.[24] In 1879 naturalist John Muir found that the ice had retreated almost all the way up the bay, a distance of around 48 miles (77 km).[25] By 1916 the Grand Pacific Glacier was at the head of Tarr Inlet about 65 miles (105 km) from Glacier Bay's mouth. This is the fastest documented glacier retreat.[16] Not all of the park's glaciers are in retreat. Two examples are the Johns Hopkins Glacier which, according to observations in 2012, has been advancing at the rate of 10 to 15 ft (3.0 to 4.6 m) per day, and the Margerie Glacier which is stable, neither advancing nor retreating.[16] Scientists working in the park and preserve hope to learn how glacial activity relates to climate change.

Ecosystems

Ecosystems in the park are wet tundra, Alpine tundra, coastal forest, and glaciers and icefields.[26]

Regions of the park closest to the Gulf of Alaska have a relatively mild climate with significant rainfall and comparatively low snowfall. Lower Glacier Bay is a transitional zone, and upper Glacier Bay is cold and snowy. Access to the land can be difficult, since the glacial fjords have steep walls that rise directly from the water. Where there are shoreline flats, they can be densely vegetated with alder and devils club, making hiking difficult.

Fauna

Wildlife in Glacier Bay includes both brown and black bear species, timber wolf, coyote, moose, black-tailed deer, Arctic and red fox species, porcupine, marmot, dall sheep, beaver, Canadian lynx, two species of otter, mink, wolverine, and mountain goat. Birds that nest in this park include the bald eagle, golden eagle, five species of woodpecker, two species of hummingbird, raven, four species of falcon, six species of hawk, osprey, and ten species of owl. Marine mammal species that swim offshore are the sea otter, harbor seal, Steller sea lion, Pacific white-sided dolphin, orca, minke whale, and humpback whale.

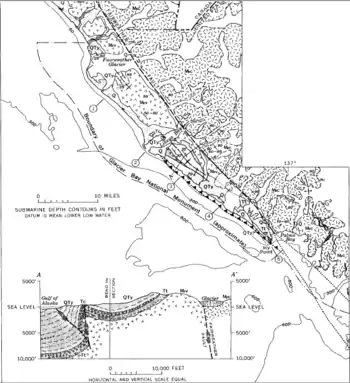

Glacier Bay Geologic column

Glacier Bay Geologic column Map of maximum glacial extent

Map of maximum glacial extent The Nunatak molybdenite location

The Nunatak molybdenite location Brady Nunatak Nickel-Copper geologic map

Brady Nunatak Nickel-Copper geologic map Fairweather Fault Geologic map

Fairweather Fault Geologic map Fairweather Fault Geologic map legend

Fairweather Fault Geologic map legend

Activities

About 80% of visitors to Glacier Bay arrive on cruise ships. The National Park Service operates cooperative programs where rangers provide interpretive services aboard the ships and on the smaller boats that offer excursion trips to more distant park features.[27] In-park accommodations are available at the Glacier Bay Lodge.[28] The park and preserve hosts many outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, mountaineering, kayaking, rafting, fishing, and bird-watching. Unlike many other national parks in Alaska, subsistence hunting is not allowed in the park, only in the preserve.[29]

Sport hunting and trapping are also allowed in the preserve. To hunt and trap, you must have all required licenses and permits and follow all other state regulations. The National Park Service and the State of Alaska cooperatively manage the wildlife resources of the preserve. Campers and hunters should be aware that brown bears are common in the preserve and be prepared to avoid conflicts with them. Typically hunted species in the preserve include black bears, mountain goats, wolves, wolverines, snowshoe hare, ptarmigans, waterfowls and a number of furbearers. There is one big game hunting guide authorized through concession contracts to operate within Glacier Bay National Preserve. Three lodges and one outfitter can provide transportation and services for fishing and hunting small game and waterfowl.[30]

Sport fishing is another activity popular in the park. Halibut are frequently esteemed by deep-sea fishers and in rivers and lakes Dolly Varden and rainbow trout provide sport. An Alaskan sportfishing license is required for all nonresidents 16 and older, and residents 16–59, to fish in Alaska's fresh and salt waters.[31]

Human history

Prehistory and exploration

The earliest traces of human occupation at Glacier Bay date to about 10,000 years before the present, with archaeological sites just outside the park dating to that time.[32] Evidence of human activity is scarce, because so much of the area is or was glaciated for much of the period and because advancing glaciers may have scoured all traces of historical occupation from their valleys. Ongoing uplift of the land may reveal new sites that had been submerged by rising sea levels. Most archaeological evidence is from the last 200 years. The Haida, Eyak and Tlingit all could have occupied the coast until historical times, when the Tlingit came to dominate the area.

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse was the first European to explore the Alaskan coast on foot in the region of Glacier Bay in 1786, arriving in Lituya Bay and making contact with the Tlingit. Russian fur traders also probably visited the region in the mid-18th century. The region was later visited by George Vancouver in Discovery in 1794, during the Vancouver Expedition.[33] The explorers are believed to have seen the Glacier Bay ice at its peak, which coincided with their visits.[34] Russians were chiefly concerned with the area until the 1880s, when Americans were drawn to Alaska and the Klondike by the Klondike Gold Rush of the 1890s.[33]

John Muir visited Glacier Bay in 1879, just prior to the 1880 establishment of Yosemite National Park, Muir's first great cause. Muir came to Alaska to learn about glaciers as a means of understanding the formation of the glaciated landscape of the Yosemite Valley. Muir sent dispatches back to San Francisco to be published in the San Francisco Bulletin in both 1879 and 1880, eventually collecting these stories, accounts of his third and fourth trips in 1890 and 1899, and later lectures and articles into the 1915 book Travels in Alaska, promoting Glacier Bay and the Inside Passage. Muir's writings led to the naming of Muir Glacier, then nearly 300 feet (91 m) tall at tidewater and the most active glacier in the bay, after Muir.[35]

The Pacific Coast Steamship Company ran tours up the Inside Passage from Tacoma and Portland during the 1890s, highlighting Muir Glacier and Glacier Bay. The accessibility of Glacier Bay brought naturalists and geologists to study, survey and name the glaciers. The Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899 was organized by railroad executive Edward Harriman who recruited Muir, George Bird Grinnell, photographer Edward S. Curtis and several others to study the Alaska coast on a specially-outfitted ship, spending five days at Glacier Bay. The expedition noted significant glacial retreat. A few months later, the magnitude 8.0 earthquake that shook Yakutat Bay on September 10, 1899, caused Muir Glacier to collapse into the bay, filling it and making it less accessible and attractive to tourists.[36] After 1900, Taku Glacier became a popular destination.[35] A salmon cannery was established in 1900 at Dundas Bay, employing native, white, and Chinese laborers and operating until 1931.[36]

Muir's writings attracted the attention of William Skinner Cooper, an ecologist at the University of Minnesota, who saw the bay's retreating glaciers as an opportunity to study plant succession on the recently exposed land. He visited Glacier Bay in 1916, surveying the glaciers and inlets and establishing nine test plots to be monitored in future visits. Cooper returned to Glacier Bay in 1922, wrote a paper for the Ecological Society of America in which he proposed that Glacier Bay be protected as a national monument.[35][37]

The Ecological Society established a committee to promote the designation of Glacier Bay as a national monument at the urging of Cooper, forwarding copies of their resolutions to President Calvin Coolidge, the National Park Service, the Smithsonian and the governor of Alaska. The idea was opposed by the U.S. Geological Survey, which reported that the area had potential for mineral extraction. The Interior Department decided to send an agent to survey the area, assigning George Alexander Parks of the General Land Office, and a future governor of Alaska, to examine the area and to canvass local residents. Parks' 1924 report recommended a very limited boundary designed to include glaciers and little else. In response Cooper and the Ecological Society undertook a letter-writing campaign that supported the park Service and caused Coolidge to add some portions of mature forest to the park's boundaries. Coolidge's proclamation under the Antiquities Act of Glacier Bay National Monument came on February 26, 1925.[38]

National monument

Alaska game managers came under heavy criticism in the 1920s for a perceived lack of interest in protecting Alaskan brown bears. The state approached the Park Service with a proposal to expand the boundaries of the Glacier Bay monument using land from Tongass National Forest as a bear sanctuary. Park Service studies were favorable, and the Forest Service came to view an expansion of Glacier Bay as preferable to the designation of Admiralty Island as a national park, which was first proposed in the 1930s. By the late 1930s Ernest Gruening, the director of the Department of Territories and Island Possessions and future governor of Alaska, suggested that the entire region be protected in a single unit extending up the Saint Elias Range to the Wrangell Range. The substance of Gruening's idea would not be realized until 1978, when Wrangell-St. Elias National Monument would be proclaimed. In the meantime, the Wrangell-St. Elias proposal was set aside in favor of expansions to the east for bear habitat and to the west to protect the Gulf of Alaska coastline. President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act to expand the monument on April 18, 1939, creating the largest unit in the national park system at the time.[39]

During World War II the U.S. Army appropriated an area around Excursion Inlet to be used as a logistics base for transferring materiel from barges transiting the Inside Passage to seagoing vessels, logging the area for pilings to be used in piers. The base was never used. At the same time the Army built an airfield at Gustavus, which offered flat terrain and good weather. The airfield was completed too late to participate in the Aleutian Campaign. However, it was one of four Alaskan airfields suitable for use by B-29s, with 5,000-foot (1,500 m) and 7,500-foot (2,300 m) runways and modern navigation equipment.[40] In 1955 the area around Gustavus was removed from the monument and returned to the public domain, together with 10,184 acres (4,121 ha) at Excursion Inlet.[41]

No Park Service personnel were assigned to the monument until 1949, when a seasonal ranger was stationed at Bartlett Cove. The monument was administered locally from 1953 onwards. Starting in 1957 the facilities at Bartlett Cove were expanded as part of the Park Service's Mission 66 program with employee housing and maintenance facilities. An administrative site was also developed outside the monument boundaries at the Forest Service ranger station at Indian Point on Auke Bay, closer to Juneau.[41] The Glacier Bay Lodge was built to accommodate guests in 1966. Beginning in 1969 cruise ships became regular visitors to the monument.[28]

In 1958 survey crews found a rich deposit of copper and nickel ore under the Brady Icefield. Investigators looked at a nunatak outcrop in the icefield and found highly mineralized rock. Newmont Exploration Ltd. proposed the construction of a 3-mile (4.8 km) adit to an underground mine under the icefield, with a mill at the portal opening and a road to piers at Dixon Bay. This proposal took advantage of 1936 legislation that permitted mineral exploitation in the monument, which had been confined to small prospectors until this time. In response to this and other proposals, Montana senator Lee Metcalf proposed the Mining in the Parks Act to resolve and eventually prohibit mining at Glacier Bay and five other parks and monuments. However, the final bill contained a number of significant exemptions, and the Newmont claim has never been resolved, although no mining activity has been proposed since the 1970s.[42][43][44]

National park and preserve

As a result of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), 80,000,000 acres (32,000,000 ha) of Alaskan public lands were eligible for inclusion in the national park system. Studies for expansion of Glacier Bay focused on the area around the Alsek River. Facing an approaching deadline imposed by ANCSA to resolve land allotment and seeing delays in the proposed Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in Congress that was intended to make a final settlement, President Jimmy Carter used his authority under the Antiquities Act to proclaim fifteen National Park Service units in Alaska on December 1, 1978. The proclamation also expanded Glacier Bay National Monument to include the Alsek lands. The final ANILCA legislation, signed into law by Carter on December 2, 1980, established Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve from the national monument. The Alsek addition comprised the bulk of the preserve lands. The chief distinction between park and preserve lands is that sport hunting by non-residents is permitted in accordance with Alaskan game regulations in the preserve, but prohibited in the park.[45]

World Heritage Site

The Kluane-Wrangell-St. Elias-Glacier Bay-Tatshenshini-Alsek transborder park system comprising Kluane, Wrangell-St Elias, Glacier Bay and Tatshenshini-Alsek parks, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 for the spectacular glacier and icefield landscapes as well as for the importance of grizzly bears, caribou and Dall sheep habitat. The Glacier Bay National Park was added in 1992 to the Heritage Site.[46]

References

- "Protected Planet | Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve". Protected Planet. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- Lee, Robert F. "The Story of the Antiquities Act". National Park Service Archaeology Program. Retrieved 3 March 2012. Chapter 8

- "Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act". Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012. Title 2, section 202(1).

- Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve (April 2010). "Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve Foundation Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- National Park Service Office of Public Affairs and Harpers Ferry Center (July 2009). "The National Parks: Index 2009–2011". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Rossman, Darwin (1963). Geology of the Eastern Part of the Mount Fairweather Quadrangle, Glacier Bay, Alaska, USGS Bulletin 1121-K. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. K1, K24–K25, K28, K32–K33.

- Sanford, R.S.; Apell, G.A.; Rutledge, F.A. (March 1949). Investigation of Muir Inlet or Nunatak Molybdenum Deposits, Glacier Bay, Southeastern Alaska, R.I. 4421. US Dept. of the Interior Bureau of Mines. pp. 1–6.

- Twenhofel, W.S. (1946). Molybdenite Deposits of the Nunatak Area, Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay, in Molybdenite Investigations in Southeastern Alaska, USGS Bulletin 947-B. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 9–18.

- MacKevett, E.M.; Brew, D.A.; Hawley, C.C.; Huff, L.C.; Smith, J.G. (1971). Mineral Resources of Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska, USGS Professional Paper 632. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 56–68.

- Rossman, Darwin (1959). Geology and Ore Deposits in the Reid Inlet Area, Glacier Bay, Alaska, USGS Bulletin 1058-B. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 38–39.

- "Landslides and Giant Waves". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Natural Features & Ecosystems". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Map of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve". National Park Service. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - National Park Service (2010). "Glacier Bay Park & Preserve Factsheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- National Park Service. "Glacier Bay Rafting".

- "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- "Glacier Bay, Alaska – Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary – 1966 to 2015". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 16 Jan 2016.

- "Glacier Bay Fact Sheet" (PDF). Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Glaciers / Glacial Features". U.S. National Park Service. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Glaciers with water termini (image)". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Lawson, Daniel E. (Feb 2004). "An Overview of Selected Glaciers in Glacier Bay" (PDF). Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Vancouver, George, and John Vancouver (1801). A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World, Vols. I-VI. London: J. Stockdale.

- Muir, John. "Travels in Alaska". Sierra Club. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Natural History of Glacier Bay". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Things to Do". Glacier Bay National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Catton, Ch. 8

- "HowStuffWorks "Subsistence Hunting Locations". HowStuffWorks.

- "Hunting in Glacier Bay National Preserve – Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve". National Park Service. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Sport Fishing – Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve". National Park Service. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Early Peoples". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. Jan 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "A timeline of human history" (PDF). Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Catton, Ch.1

- Catton, Ch. 2

- "Following the quake of 1899". Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "The scientists". Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. National Park Service. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Catton, Ch. 3

- Catton, Ch. 4

- Catton, Ch. 5

- Catton, Ch. 7

- Catton, Ch. 9

- "Monument formation". Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. National Park Service. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- USGS report on the Brady Glacier nickel-copper deposit

- Catton, Ch. 11

- UNESCO decision

Bibliography

- Catton, Theodore (1995) Land Reborn: A History of Administration and Visitor Use in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Glacier Bay National Park. |

- Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve – National Park Service site

- Alaska – National Park Service Alaska Regional Office

- World Heritage Site – UNESCO