Giuseppe Arcimboldo

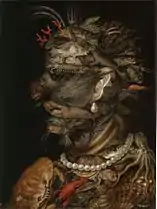

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe artʃimˈbɔldo];[1] also spelled Arcimboldi) (1526 or 1527 – 11 July 1593) was an Italian painter best known for creating imaginative portrait heads made entirely of objects such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish and books.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, now in National Gallery in Prague, Google Art Project | |

| Born | 1527 |

| Died | 11 July 1593 (aged 66–67) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | The Librarian, 1566 Vertumnus, 1590–1591 |

These works form a distinct category from his other productions. He was a conventional court painter of portraits for three Holy Roman Emperors in Vienna and Prague, also producing religious subjects and, among other things, a series of coloured drawings of exotic animals in the imperial menagerie. He specialized in grotesque symbolical compositions of fruits, animals, landscapes, or various inanimate objects arranged into human forms.[2] The still-life portraits were clearly partly intended as whimsical curiosities to amuse the court, but critics have speculated as to how seriously they engaged with Renaissance Neo-Platonism or other intellectual currents of the day.

Biography

Giuseppe's father, Biagio Arcimboldo, was an artist of Milan. Like his father, Giuseppe Arcimboldo started his career as a designer for stained glass and frescoes at local cathedrals when he was 21 years old.[3]

In 1562, he became court portraitist to Ferdinand I at the Habsburg court in Vienna, Austria and later, to Maximilian II and his son Rudolf II at the court in Prague. He was also the court decorator and costume designer. Augustus, Elector of Saxony, who visited Vienna in 1570 and 1573, saw Arcimboldo's work and commissioned a copy of his The Four Seasons which incorporates his own monarchic symbols.

Arcimboldo's conventional work, on traditional religious subjects, has fallen into oblivion, but his portraits of human heads made up of vegetables, plants, fruits, sea creatures and tree roots, were greatly admired by his contemporaries and remain a source of fascination today.

At a distance, his portraits looked like normal human portraits. However, individual objects in each portrait were actually overlapped together to make various anatomical shapes of a human. They were carefully constructed by his imagination. The assembled objects in each portrait were not random: each was related by characterization.[4] In the portrait now represented by several copies called The Librarian, Arcimboldo used objects that signified the book culture at that time, such as the curtain that created individual study rooms in a library. The animal tails, which became the beard of the portrait, were used as dusters. By using everyday objects, the portraits were decoration and still-life paintings at the same time.[5] His works showed not only nature and human beings, but also how closely they were related.[6]

After a portrait was released to the public, some scholars, who had a close relationship with the book culture at that time, argued that the portrait ridiculed their scholarship. In fact, Arcimboldo criticized rich people's misbehavior and showed others what happened at that time through his art. In The Librarian, although the painting might have appeared ridiculous, it also contained a criticism of wealthy people who collected books only to own them, rather than to read them.[5]

Art critics debate whether his paintings were whimsical or the product of a deranged mind.[7] A majority of scholars hold to the view, however, that given the Renaissance fascination with riddles, puzzles, and the bizarre (see, for example, the grotesque heads of Leonardo da Vinci), Arcimboldo, far from being mentally imbalanced, catered to the taste of his times.

Arcimboldo died in Milan, where he had retired after leaving the Prague service. It was during this last phase of his career that he produced the composite portrait of Rudolph II (see above), as well as his self-portrait as the Four Seasons. His Italian contemporaries honored him with poetry and manuscripts celebrating his illustrious career.

When the Swedish army invaded Prague in 1648, during the Thirty Years' War, many of Arcimboldo's paintings were taken from Rudolf II's collection.

His works can be found in Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum and the Habsburg Schloss Ambras in Innsbruck; the Louvre in Paris; as well as in numerous museums in Sweden. In Italy, his work is in Cremona, Brescia, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut; the Denver Art Museum in Denver, Colorado; the Menil Foundation in Houston, Texas; the Candie Museum in Guernsey and the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid also own paintings by Arcimboldo.

He is known as a 16th-century Mannerist. A transitional period from 1520 to 1590, Mannerism adopted some artistic elements from the High Renaissance and influenced other elements in the Baroque period. A Mannerist tended to show close relationships between human and nature.[8] Arcimboldo also tried to show his appreciation of nature through his portraits. In The Spring, the human portrait was composed of only various spring flowers and plants. From the hat to the neck, every part of the portrait, even the lips and nose, was composed of flowers, while the body was composed of plants. On the other hand, in The Winter, the human was composed mostly of roots of trees. Some leaves from evergreen trees and the branches of other trees became hair, while a straw mat became the costume of the human portrait.

Legacy

In 1976, the Spanish sculptor Miguel Berrocal created the original bronze sculpture interlocking in 20 elements titled Opus 144 ARCIMBOLDO BIG as a homage to the Italian painter. This work was followed by the limited-edition sculpture in 1000 copies titled Opus 167 OMAGGIO AD ARCIMBOLDO (HOMAGE TO ARCIMBOLDO) of 1976–1979 consisting of 30 interlocking elements.

The works of Arcimboldo, especially his multiple images and visual puns, were rediscovered in the early 20th century by Surrealist artists such as Salvador Dalí. The exhibition entitled "The Arcimboldo Effect: Transformations of the face from the 16th to the 20th Century” at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1987) includes numerous 'double meaning' paintings. Arcimboldo's influence can also be seen in the work of Shigeo Fukuda, István Orosz, Octavio Ocampo, Vic Muniz, and Sandro del Prete, as well as the films of Jan Švankmajer.[9]

Arcimboldo's works are used by some psychologists and neuroscientists to determine the presence of lesions in the hemispheres of the brain that recognize global and local images and objects.

Art heritage, estimates

Heritage

.jpg.webp)

Giuseppe Arcimboldo did not leave written certificates on himself or his artwork. After the deaths of Arcimboldo and his patron—the emperor Rudolph II—the heritage of the artist was quickly forgotten, and many of his works were lost. They were not mentioned in the literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Only in 1885 did the art critic K. Kasati publish the monograph "Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Milan Artist" in which the main attention was given to Arcimboldi's role as a portraitist.[10]

With the advent of surrealism its theorists paid attention to the formal work of Arcimboldo, and in the first half of the 20th century many articles were devoted to his heritage. Gustav Hocke [de] drew parallels between Arcimboldo, Salvador Dalí, and Max Ernst's works. A volume monograph of B. Geyger and the book by F. Legrand and F. Xu were published in 1954.

Since 1978 T. DaCosta Kaufmann was engaged in Arcimboldo's heritage, and wrote of the artist defending his dissertation "Variations on an imperial subject". His volume work, published in 2009, summed up the attitude of modern art critics towards Arcimboldo. An article published in 1980 by Roland Barthes was devoted to Arcimboldo's works.[10]

Archimboldo's relation with surrealism was emphasized at landmark exhibitions in New York ("Fantastic art, dada, surrealism", 1937) and in Venice ("Arcimboldo's Effect: Evolution of the person in painting from the XVI century", Palazzo Grassi, 1987) where Arcimboldo's allegories were presented.[11] The largest encyclopedic exhibition of Arcimboldo's heritage, where about 150 of his works were presented, including graphics, was held in Vienna in 2008. In spite of the fact that very few works of Arcimboldo are available in the art market, their auction cost is in the range of five to 10 million dollars. Experts note that it is very modest for an artist at such a level of popularity.[12][13]

Arcimboldo's art heritage is badly identified, especially as it concerns his early works and pictures in traditional style. In total about 20 of his pictures remain, but many more have been lost, according to mentions of his contemporaries and documents of the era. His cycles Four Elements and Seasons, which the artist repeated with little changes, are most known. Some of his paintings include The Librarian, The Jurist, The Cook, Cupbearer, and other pictures.[14] Arcimboldo's works are stored in the state museums and private collections of Italy (including Uffizi Gallery), France (Louvre), Austria, the Czech Republic, Sweden, and in the US.

Art interpretations

The main object of modern art critics' interpretation are the "curious" paintings of Arcimboldo whose works, according to V. Krigeskort, "are absolutely unique".[15] Attempts of interpretation begin with judgments of the cultural background and philosophy of the artist, however a consensus in this respect is not developed. B. Geyger, who for the first time raised these questions, relied mainly on judgments of contemporaries—Lomazzo, Comanini, and Morigia, who used the terms "scherzi, grilli, and capricci" (respectively, "jokes", "whims", "caprices").[11] Geyger's monograph is entitled: "Comic pictures of Giuseppe Arcimboldo". Geyger considered the works of the artist as inversion, when the ugliness seems beautiful, or, on the contrary, as the disgrace exceeding the beauty, entertaining the regal customer.[16] A similar point of view was stated by Barthes, but he reduced works of the artist to the theory of language, believing that fundamentals of Arcimboldo's art philosophy is linguistic, because without creating new signs he confused them by mixing and combining elements that then played a role in the innovation of language.[17]

Arcimboldo speaks double language, at the same time obvious and obfuscatory; he creates "mumbling" and "gibberish", but these inventions remain quite rational. Generally, the only whim (bizarrerie) which isn't afforded by Arcimboldo – he doesn't create language absolutely unclear … his art not madly.[18]

Arcimboldo's classification as mannerist also belongs to the 20th century. Its justification contains in Gustav Rehn Hok's work The world as a Labyrinth, published in 1957. Arcimboldo was born in the late Renaissance, and his first works were done in a traditional Renaissance manner. In Hok's opinion, during the Renaissance era the artist had to be first of all the talented handicraftsman who skillfully imitated the nature, as the idea of fine art was based on its studying. Mannerism differed from the Renaissance art in attraction to "not naturalistic abstraction". It was a continuation of artistic innovation in the late Middle Ages—art embodying ideas. According to G. Hok, in consciousness there is concetto—the concept of a picture or a picture of the concept, an intellectual prototype. Arcimboldo, making a start from concetti, painted metaphorical and fantastic pictures, extremely typical for manneristic art.[19] In On Ugliness, which was published under Umberto Eco's edition, Arcimboldo also admitted belonging to manneristic tradition for which "...the preference for aspiration to strange, extravagant and shapeless over expressional fine" is peculiar.[20]

In the work Arcimboldo and archimboldesk, F. Legrand and F. Xu tried to reconstruct philosophical views of the artist. They came to a conclusion that the views represented a kind of Platonic pantheism. The key to reconstruction of Arcimboldo's outlook seemed to them to be in the symbolism of court celebrations staged by the artist, and in his allegorical series. According to Plato's dialogues "Timaeus", an immemorial god created the Universe from chaos by a combination of four elements – fire, water, air and the earth, as defines all-encompassing unity.[21] In T. Dakosta Kauffman's works serious interpretation of heritage of Arcimboldo in the context of culture of the 16th century is carried out consistently. Kauffman in general was skeptical about attribution of works by Arcimboldo, and recognized as undoubted originals only four pictures, those with a signature of the artist. He based the interpretation on the text of the unpublished poem by J. Fonteo "The picture Seasons and Four Elements of the imperial artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo". According to Fonteo, the allegorical cycles of Arcimboldo transfer ideas of greatness of the emperor. The harmony in which fruits and animals are combined into images of the human head symbolizes harmony of the empire under the good board of the Habsburgs. Images of seasons and elements are always presented in profile, but thus Winter and Water, Spring and Air, Summer and Fire, Fall and Earth are turned to each other. In each cycle symmetry is also observed: two heads look to the right, and two — to the left. Seasons alternate in an invariable order, symbolizing both constancy of the nature and eternity of board of the Habsburgs' house. The political symbolics also hints at it: at the image of Air there are Habsburg symbols — a peacock and an eagle and Fire is decorated with a chain of the Award of the Golden Fleece, a great master of which by tradition was a head of a reigning dynasty. However it is made of flints and shod steel. Guns also point to the aggressive beginning. The Habsburg symbolics is present in the picture Earth, where the lion's skin designates a heraldic sign of Bohemia. Pearls and corals similar to cervine horns in Water hint at the same. [22][23]

In literature and popular culture

A number of writers from seventeenth-century Spain allude to his work, given that Philip II had acquired some of Arcimboldo's paintings. Grotesque images in the Miguel de Cervantes novel Don Quixote, such as an immense fake nose, recall his work.[24] He also appears in the works of Francisco de Quevedo.[25] Turning to contemporary Latin American literature, he appears in Roberto Bolaño's 2666, in which the author uses the painter's name for one of the main characters, Benno von Archimboldi.

Arcimboldo's painting Water was used as the cover of the 1975 album Masque by the progressive rock band Kansas, and was also shown on the cover of the 1977 Paladin edition of Thomas Szasz's The Myth of Mental Illness.[26]

The 1992 novelette The Coming of Vertumnus by Ian Watson counterpoints the innate surrealism of the eponymous work against a drug-induced altered mental state.

In Harry Turtledove's 1993 fantasy detective novel, The Case of the Toxic Spell Dump, the alternate history's version of Arcimboldo incorporated imps – a common, everyday sight in that world – along with fruit, books, etc., into his iconic portraits.

The logo of the Arkangel Shakespeare audiobooks, released from 1998 onwards, is a portrait of William Shakespeare made out of books, in the style of Arcimboldo's Librarian.

Arcimboldo-style fruit people appear as characters in the films The Tale of Despereaux (2008) and Alice Through the Looking Glass (2016), as well as in the Cosmic Osmo video game series.

Arcimboldo's surrealist imagination is visible also in fiction. The first and last sections of 2666 (2008), Roberto Bolaño's last novel, concern a fictional German writer named Archimboldi, who takes his pseudonym from Arcimboldo.[27]

A detail from Flora was used on the cover of the 2009 album Bonfires on the Heath by The Clientele.

Aricimboldo is referenced in the 2020 revival of the Animaniacs, Episode 4, as the main characters create a sculpture of him made of fruit.

Gallery

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. of Austria and his wife Infanta Maria of Spain with their children, ca. 1563, Ambras Castle

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. of Austria and his wife Infanta Maria of Spain with their children, ca. 1563, Ambras Castle_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15897.tif.jpg.webp) The Jurist, 1566, Nationalmuseum, Sweden

The Jurist, 1566, Nationalmuseum, Sweden The Librarian, 1566, oil on canvas, Skokloster Castle, Sweden

The Librarian, 1566, oil on canvas, Skokloster Castle, Sweden The Waiter, 1574

The Waiter, 1574

Four Seasons

Spring,[28] 1563 Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

Spring,[28] 1563 Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid Summer, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Summer, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Autumn, 1573, Louvre Museum, Paris

Autumn, 1573, Louvre Museum, Paris Winter, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Winter, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Four elements

.jpg.webp) Air, ca. 1566, (copy), private collection

Air, ca. 1566, (copy), private collection Fire, Oil on Wood, 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

Fire, Oil on Wood, 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria Earth, possibly 1566, private collection, Austria

Earth, possibly 1566, private collection, Austria Water, 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

Water, 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

References

- Luciano Canepari. "Arcimboldo". DiPI Online (in Italian). Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Oxford illustrated encyclopedia. Judge, Harry George., Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. 1985–1993. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-869129-7. OCLC 11814265.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Giuseppe Arcimboldo Biography". Giuseppe-arcimboldo.org. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- Maiorino, Giancarlo. The Portrait of Eccentricity: Arcimboldo and the Mannerist Grotesque. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991. Print.

- Elhard, K. C. "Reopening the Book on Arcimboldo’s Librarian." Libraries & Culture 40.2 Spring 2005. 115–127. Project MUSE.

- ROSENBERG, KAREN (September 23, 2010). "Several Obsessions, United on the Canvas". NY Times. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Melikian, Souren (October 5, 2007). "Giuseppe Arcimboldo's hallucinations: Fantasy or insanity?". NY Times. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "The Mannerist Style and the Lamentation". Artsconnected.org. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- [Literature:The Arcimboldo Effect: Transformations of the face from the 16th to the 20th Century. Abbeville Press, New York, 1st Edition (September 1987). ISBN 0896597695. ISBN 978-0896597693.]

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Ferino-Pagden 2007, p. 15.

- Carol Vogel (September 16, 2010). "Arcimboldo Work Bought in Time for Exhibition". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- Blake Gopnik (September 17, 2010). "Arcimboldo's 'Four Seasons' will join National Gallery of Art collection". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. p. 16—20. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Roland Barthes. Arcimboldo. p. 335

- Roland Barthes. Arcimboldo. p. 338

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Storia della bruttezza (Bompiani, 2007 – English translation: On Ugliness, 2007). p.169

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. pp. 58–60. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Ferino-Pagden 2007, p. 97—101.

- Werner Kriegeskorte (2000). Arcimboldo. Ediz. Inglese. Taschen. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-8228-5993-3

- Frederick A. de Armas, "Nero's Golden House: Italian Art and the Grotesque in Don Quijote, Part II," Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America 24.1 (2004): 143-71.

- Margarita Levisi,"Las figuras compuestas en Arcimboldo y Quevedo," Comparative Literature20 (1968): 217-35.

- See the 1977 Paladin edition of The Myth of Mental Illness

- Bolaño, Roberto. 2666. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008, pps. 729, 784.

- Fernando, Real Academia de BBAA de San. "Arcimboldo, Giuseppe - La Primavera". Academia Colecciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-03-31.

Readings

External links

![]() Media related to Giuseppe Arcimboldo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giuseppe Arcimboldo at Wikimedia Commons

- Giuseppe-Arcimboldo.org The Complete works by Giuseppe Arcimboldo

- Giuseppe Archimboldo collection at the Israel Museum. Retrieved September 2016.

- "Arcimboldo's Feast for the Eyes" Smithsonian Magazine