German Workers' Party

The German Workers' Party (German: Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP) was a short-lived political party established in Weimar Germany after World War I. It was the precursor of the Nazi Party, which was officially known as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP). The DAP only lasted from 5 January 1919 until 24 February 1920.

German Workers' Party Deutsche Arbeiterpartei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Party Chairman | Anton Drexler (1919–1920) |

| Deputy Chairman | Karl Harrer (1919–1920) |

| Founders | Anton Drexler Dietrich Eckart Gottfried Feder Karl Harrer |

| Founded | 5 January 1919 |

| Dissolved | 24 February 1920 |

| Merger of | • Political Workers' Circle[1][2] • Workers' Committee for a Good Peace |

| Succeeded by | NSDAP |

| Headquarters | Fürstenfelder Straße 14, Munich, Germany |

| Ideology | German nationalism Pan-Germanism Antisemitism Anti-Marxism Anti-capitalism |

| Political position | Far-right[3] |

| Colors | Black, white and red (official, German Imperial colours) Black (customary) |

History

Origins

On 5 January 1919, the German Workers' Party (DAP) was founded in Munich in the hotel Fürstenfelder Hof by Anton Drexler,[2] along with Dietrich Eckart, Gottfried Feder and Karl Harrer. It developed out of the Freier Arbeiterausschuss für einen guten Frieden (Free Workers' Committee for a Good Peace) league, a branch of which Drexler had founded in 1918.[2] Thereafter in 1918, Harrer (a journalist and member of the Thule Society), convinced Drexler and several others to form the Politischer Arbeiterzirkel (Political Workers' Circle).[2] The members met periodically for discussions with themes of nationalism and antisemitism.[2] Drexler was encouraged to form the DAP in December 1918 by his mentor, Dr. Paul Tafel. Tafel was a leader of the Alldeutscher Verband (Pan-Germanist Union), a director of the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg and a member of the Thule Society. Drexler's wish was for a political party which was both in touch with the masses and nationalist. With the DAP founding in January 1919, Drexler was elected chairman and Harrer was made Reich Chairman, an honorary title.[4] On 17 May, only ten members were present at the meeting, and a later meeting in August only noted 38 members attending.[5] The members were mainly Drexler's work colleagues from the Munich railway yards.[5]

Adolf Hitler's membership

After World War I ended, Adolf Hitler returned to Munich. Having no formal education or career prospects, he tried to remain in the army for as long as possible.[6] In July 1919, he was appointed Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance commando) of the Reichswehr to influence other soldiers and to investigate the DAP. While monitoring the activities of the DAP, Hitler became attracted to founder Anton Drexler's anti-Semitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist, and anti-Marxist ideas.[2] While attending a party meeting at the Sterneckerbräu beer hall on 12 September 1919, Hitler became involved in a heated political argument with a visitor, Professor Baumann, who questioned the soundness of Gottfried Feder's arguments in support of Bavaria separatism and against capitalism.[7] In vehemently attacking the man's arguments, he made an impression on the other party members with his oratory skills and, according to Hitler, Baumann left the hall acknowledging unequivocal defeat.[7] Impressed with Hitler's oratory skills, Drexler encouraged him to join. On the orders of his army superiors, Hitler applied to join the party.[8] Although Hitler initially wanted to form his own party, he claimed to have been convinced to join the DAP because it was small and he could eventually become its leader.[9]

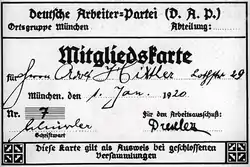

In less than a week, Hitler received a postcard stating he had officially been accepted as a member and he should come to a committee meeting to discuss it. Hitler attended the committee meeting held at the run-down Altes Rosenbad beer-house.[10] Normally, enlisted army personnel were not allowed to join political parties. In this case, Hitler had Captain Karl Mayr's permission to join the DAP. Further, Hitler was allowed to stay in the army and receive his weekly pay of 20 gold marks a week.[11] At the time when Hitler joined the party, there were no membership numbers or cards. It was in January 1920 when a numeration was issued for the first time and listed in alphabetical order Hitler received the number 555. In reality, he had been the 55th member, but the counting started at the number 501 in order to make the party appear larger.[12] In his work Mein Kampf, Hitler later claimed to be the seventh party member, and he was in fact the seventh executive member of the party's central committee.[13] After giving his first speech for the DAP on 16 October at the Hofbräukeller, Hitler quickly became the party's most active orator. Hitler's considerable oratory and propaganda skills were appreciated by the party leadership as crowds began to flock to hear his speeches during 1919–1920. With the support of Drexler, Hitler became chief of propaganda for the party in early 1920. Hitler preferred that role as he saw himself as the drummer for a national cause. He saw propaganda as the way to bring nationalism to the public.[14]

From DAP to NSDAP

The small number of party members were quickly won over to Hitler's political beliefs. He organized their biggest meeting yet of 2,000 people for 24 February 1920 in the Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München. Further in an attempt to make the party more broadly appealing to larger segments of the population, the DAP was renamed the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) on 24 February.[15][16] Such was the significance of Hitler's particular move in publicity that Harrer resigned from the party in disagreement.[17] The new name was borrowed from a different Austrian party active at the time (the Deutsche Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei, i.e. the German National Socialist Workers' Party), although Hitler earlier suggested the party to be renamed the Social Revolutionary Party. It was Rudolf Jung who persuaded Hitler to adopt the NSDAP name.[18]

Membership

Early members of the party included:

References

Citations

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 148.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 82.

- Colley 2010, p. 11.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 82, 83.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 83.

- Kershaw 1999, p. 109.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 75.

- Evans 2003, p. 170.

- Kershaw 1999, p. 126.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 75, 76.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 76.

- Mitcham 1996, p. 67.

- Werner Maser, Der Sturm auf die Republik – Frühgeschichte der NSDAP, ECON Verlag, Düsseldorf, Vienna, New York, Moscow, Special Edition 1994, ISBN 3-430-16373-0.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 81, 84, 85, 89, 96.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 87.

- Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, p. 629.

- Shirer 1960, p. 36.

- Konrad Heiden, "Les débuts du national-socialisme", Revue d'Allemagne, VII, No. 71 (Sept. 15, 1933), p. 821.

Bibliography

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York; Toronto: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

- Kershaw, Ian (1999) [1998]. Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04671-7.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (1996). Why Hitler?: The Genesis of the Nazi Reich. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-95485-7.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1997) [1991]. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80793-0.

- Colley, Rupert (2010). Hitler In An Hour. History In An Hour. ISBN 978-1-4523-1587-4.