George Grey Barnard

George Grey Barnard (May 24, 1863 – April 24, 1938), often written George Gray Barnard, was an American sculptor who trained in Paris. He is especially noted for his heroic sized Struggle of the Two Natures in Man at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, his twin sculpture groups at the Pennsylvania State Capitol, and his Lincoln statue in Cincinnati, Ohio. His major works are largely symbolical in character.[1] His personal collection of medieval architectural fragments became a core part of The Cloisters in New York City.

George Grey Barnard | |

|---|---|

Portrait of George Grey Barnard in 1908 | |

| Born | May 24, 1863 Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 24, 1938 (aged 74) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Notable work | Struggle of the Two Natures in Man Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups Abraham Lincoln (Cincinnati) |

Biography

Barnard was born in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, but grew up in Kankakee, Illinois, the son of the Reverend Joseph Barnard and Martha Grubb; the grandson and namesake of merchant George Grey Grubb; and a great-grandson of Curtis Grubb, a fourth-generation member of the Grubb iron family and a onetime owner of the celebrated Gray's Ferry Tavern outside Philadelphia.

Barnard first studied at the Art Institute of Chicago under Leonard Volk.[2] The prize he was awarded for a marble bust of a Young Girl enabled him to go to Paris,[3] where, over a period of three and half years, he attended the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1883–1887), while also working in the atelier of Pierre-Jules Cavelier. He lived in Paris for twelve years, and scored a great success with his first exhibit at the Salon of 1894. He returned to America in 1896, and married Edna Monroe of Boston. He taught at the Art Students League of New York from 1900 to 1903, succeeding Augustus Saint-Gaudens.[2] He returned to France, and spent the next eight years working on his sculpture groups for the Pennsylvania State Capitol.[2] He was elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 189x, and an academician in 1902.

A strong Rodin influence is evident in his early work. His principal works include the allegorical Struggle of the Two Natures in Man" (1894, in the Metropolitan Museum, New York); The Hewer (1902, at Cairo, Illinois); The Great God Pan (1899, at Columbia University); the Rose Maiden (c.1902, at Muscatine, Iowa); the simple and graceful Maidenhood (1896, at Brookgreen Gardens).

The Great God Pan (1899), one of the first works Barnard completed after his return to America, was originally intended for the Dakota Apartments on Central Park West. Alfred Corning Clark, builder of the Dakota, had financed Barnard's early career; when Clark died in 1896, the Clark family presented Barnard's Two Natures to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in his memory, and the giant bronze Pan was presented to Columbia University, by Clark's son, Edward Severin Clark.

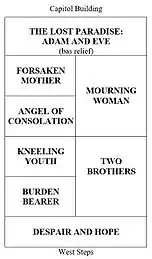

In 1911 he completed two large sculpture groups for the new Pennsylvania State Capitol: The Burden of Life: The Broken Law and Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law. Between the two groups, they feature 27 larger-than-life figures.

His larger-than-life statue of Abraham Lincoln (1917) drew heated controversy because of its rough-hewn features and slouching stance. The first casting is at Lytle Park in Cincinnati, Ohio; the second in Manchester, England (1919); and the third in Louisville, Kentucky (1922).[4]

French art dealer René Gimpel described him in his diary (1923), as "an excellent American sculptor" who is "very much engrossed in carving himself a fortune out of the trade in works of art."[5] Barnard had a commanding personal manner: "He talks of art as if it were a cabalistic science of which he is the only astrologer", wrote the unsympathetic Gimpel; "he speaks to impress. He's a sort of Rasputin of criticism. The Rockefellers are his imperial family. And the dealers court him."[6]

Interested in medieval art, Barnard gathered discarded fragments of medieval architecture from French villages before World War I.[7] He established this collection in a church-like brick building near his home in Washington Heights, Manhattan in New York City. The collection was purchased by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1925 and forms part of the nucleus of The Cloisters collection, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[8] At least one object, sold to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1924, he offered with misleading provenance.[9]

Barnard died following a heart attack on April 24, 1938 at the Harkness Pavilion, Columbia University Medical Center in New York. He was working on a statue of Abel, betrayed by his brother Cain, when he fell ill. He is interred at Harrisburg Cemetery in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

1913 Assessment by Lorado Taft

1913 assessment by Lorado Taft:

George Grey Barnard is a Westerner, although he chanced to be born in Pennsylvania, where his parents were temporarily residing in 1863. The sculptor's father is a clergyman, and the fortunes of the ministry afterward led him to Chicago, and thence to Muscatine, Iowa, where the son passed his boyhood. One cannot doubt that these circumstances had their profound influence upon the character of the young artist. In it is something of the largeness of the western prairies, something of the audacity of a life without tradition or precedent, a burning intensity of enthusiasm; above all, a strong element of mysticism which permeates all that Barnard does or thinks.

The stories of his student struggles in Chicago and Paris are familiar. The first result of all this self sacrifice became tangible in that early group, a tombstone for Norway, in which the youth portrayed "Brotherly Love," a work of "weird and indescribable charm."

In 1894 Barnard completed his celebrated group, Two Natures, upon which he had toiled, in clay and marble, for several years. This achievement gave him at once high standing in Europe, and his work has been of interest to the cultivated public of the world's capitals. Then followed an extraordinary Norwegian Stove, a monumental affair illustrative of Scandinavian mythology; and Maidenhood and the Hewer.

The great work of Barnard's recent years has been the decoration of the Pennsylvania capitol. It has been said of him that he was "the only one connected with that building who was not smirched"; but his part is a story of heroism and triumph. The writer has not yet seen the enormous groups in place, but is familiar with fragments that have won the enthusiastic praise of the best sculptors of Paris. They are inspiring conceptions which point the way to still mightier achievements in American sculpture.[10]

Selected works

- The Boy (marble, 1885), private collection

- Cain (1886, destroyed)

- Brotherly Love (Two Friends) (marble, 1886–87), Langesund, Norway.

- Brotherly Love (bronze, 1886–87), Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.[11]

- Brotherly Love (marble, 1894), Edward Severin Clark monument, Lakewood Cemetery, Cooperstown, New York.[12]

- Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (marble, 1892–1894), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Maidenhood (Innocence) (1896), Brookgreen Gardens, Murrell's Inlet, South Carolina. Evelyn Nesbitt posed as the model.[13]

- Maiden with the Roses (Rose Maiden) (marble, 1898), Greenwood Cemetery, Muscatine, Iowa

- Urn of Life (1898–1900), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[14] Created to hold the ashes of Metropolitan Opera conductor Anton Seidl.[15]

- The Mystery of Life (marble, 1895–1897), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.[16]

- The Birth (marble, 1895–1897). Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.[16]

- Solitude (Adam and Eve) (marble, c.1906). Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.[16] Marble versions are at the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, Ohio;[17] the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia;[18] and the Loeb Art Center in Poughkeepsie, New York.[19]

- The Great God Pan (1899), Dodge Hall Quadrangle, Columbia University, New York City. Exhibited at 1900 Paris Exposition,[20] and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

- Transportation – Henry Bradley Plant Fountain (1900), University of Tampa, Tampa, Florida

- The Hewer (1902), Halliday Park, Cairo, Illinois, dedicated 1906. Exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair.[21]

- Architectural sculpture (1902–03), New Amsterdam Theatre, 214 West 42nd Street, Manhattan, New York City. Barnard's façade and roof garden sculptures were removed in 1937, and are unlocated.[23]

- The Prodigal Son (1904). One of the sculptures for Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law, at the Pennsylvania State Capitol.

- The Prodigal Son (marble, 1904–1906), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[24] Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.[16]

- The Prodigal Son (marble, 1904), Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky.[25]

- 2 pedimental sculpture groups: History; The Arts (1913–1917), Main Branch, New York Public Library, Manhattan

- Rising Woman (marble, c.1916), Kykuit, Pocantico Hills, New York.

- A plaster version is at Schwab Auditorium, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.[22]

- Statue of Abraham Lincoln (bronze, 1917), Lytle Park, Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Abraham Lincoln (bronze, 1919 casting), Lincoln Square, Manchester, England

- Abraham Lincoln (bronze, 1922 casting), Louisville, Kentucky.

- Head of Abraham Lincoln (marble, 1919), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[26]

- Let There Be Light (bronze, c.1922), Isaac Wolfe Bernheim monument, Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest, Clermont, Kentucky.

- Adam and Eve Fountain (1923) Kykuit, Pocantico Hills, New York.

- The Refugee (Grief) (marble, by 1930), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[29]

Gallery

.JPG.webp) Brotherly Love (1886–87), Langesund, Norway.

Brotherly Love (1886–87), Langesund, Norway. Maidenhood (1896), Brookgreen Gardens.

Maidenhood (1896), Brookgreen Gardens. Urn of Life (1898-1900), Carnegie Museum of Art.

Urn of Life (1898-1900), Carnegie Museum of Art. The Great God Pan (1899), Columbia University, New York City

The Great God Pan (1899), Columbia University, New York City Transportation - Henry Bradley Plant Fountain (1900), Tampa, Florida.

Transportation - Henry Bradley Plant Fountain (1900), Tampa, Florida. Barnard at work on The Hewer (c.1902).

Barnard at work on The Hewer (c.1902). Solitude (Adam and Eve) (1906), Taft Museum of Art.

Solitude (Adam and Eve) (1906), Taft Museum of Art. The Birth (1913).

The Birth (1913). Abraham Lincoln (1919), Manchester, England.

Abraham Lincoln (1919), Manchester, England. Let There Be Light (c.1922), Claremont, Kentucky.

Let There Be Light (c.1922), Claremont, Kentucky.

Legacy

- Among Barnard's students were Anna Hyatt Huntington, Abastenia St. Leger Eberle, Beatrice Ashley Chanler and Malvina Hoffman.[32]

- Barnard donated 100 of his plaster models to the Kankakee County Museum in Kankakee, Illinois.[33][lower-alpha 1]

- A collection of his Medieval architectural elements is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- The George Grey Barnard Sculpture Garden was created in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania (his birthplace) in 1978.[37]

Notes

- In December 2015, a plaster of a hand, a preliminary study for Barnard's 1917 Abraham Lincoln, was stolen from the Kankakee County Museum.[34] In January 2016, Stephen Colbert mentioned the theft on the Late Show.[35] The hand was returned to the Museum in February 2017, after being found at a local church. The thief was never identified.[36]

References

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- "George Grey Barnard (1863–1938)," in Lauretta Dimmick and Donna J. Hassler. American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born before 1865. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999. pp. 421–27.

- "Barnard, George Grey". Oxford Art Online - Bénézit Dictionary of Artists. 31 October 2011. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00012046.

- "Kentucky's Abraham Lincoln," (PDF) from Kentucky Historical Society.

- Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer (John Rosenberg, tr.) 1966:211.

- Gimpel, Diary 15 January 1923.

- "Rare Relics Kept from America by French Protest". The New York Times. June 15, 1913.

- "The Cloisters Museum and Gardens". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "Retable of the Virgin". MFA Boston. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Lorado Taft, "Famous American Sculptors," The Mentor (magazine), vol. 1, no. 36, (October 20, 1913).

- Brotherly Love, from Clark Art Institute.

- Brotherly Love, from SIRIS.

- Paula Uruburu, American Eve:Evelyn Nesbitt, Stanford White, the Birth of the It Girl and the Crime of the Century, (Riverhead Books, 2009), p. 139.

- The Urn of Life, from SIRIS.

- Michael Belman, "Restoring the Urn of Life," from Carnegie Museum of Art.

- Gallery A, No. 1000 – Catalogue of International Exhibition of Modern Art, Association of American Painters and Sculptors, Armory Show, New York. Published 1913

- Solitude, from SIRIS.

- Solitude, from SIRIS.

- Solitude, from SIRIS.

- Noyes, Platt, Official Illustrated Catalogue, Fine Arts Exhibit, United States of America, Paris Exposition, 1900, (U.S. Commission to the Paris Exposition, 1900), p. 94.

- The World's Work, 1902–03: Barnard at work on The Hewer

- Claudia Cook, "Case of the Unknown Sculptures," Daily Collegian (Penn State University), November 12, 1982.

- Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, The Landmarks of New York, Fifth Edition: An Illustrated Record of the City's Historic Buildings (SUNY Press, 2011), p.420.

- The Prodigal Son, from Carnegie Museum of Art.

- The Prodigal Son, from SIRIS.

- Head of Abraham Lincoln, from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Immortality, from SIRIS.

- Let There Be Light, from Waymarking.

- The Refugee, from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law, from SIRIS.

- The Burden of Life: The Broken Law, from SIRIS.

- Joan A. Marter, ed., "George Grey Barnard," The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1, (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 202–04.

- Don Ward, "Sculptor Barnard left a controversial legacy," Round About Madison (Madison, Indiana), February 2012.

- Mitch Smith, "Who's Steal Lincoln's Hand? Art Theft Baffles Illinois Museum," The New York Times, January 3, 2016.

- http://www.daily-journal.com/news/local/lincoln-artifact-stolen-from-county-museum/article_2cb631a1-e54f-565c-8c09-3b55dac394bb.html

- http://www.daily-journal.com/news/local/after-months-stolen-lincoln-s-hand-returned-to-museum/article_ae1313b6-15d6-511f-8b64-9471399a595a.html

- "Talleyrand Park," from Bellefonte Historical and Cultural Association.

Further reading

- Thaw, Alexander Blair (December 1902). "George Grey Barnard, Sculptor". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. V: 2837–2853. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- Harold E. Dickson, ed. George Grey Barnard: Centenary Exhibition, 1863–1963 (exh. cat. Pennsylvania State University, 1964).

- Sara Dodge Kimbrough, Drawn from Life: The Story of Four American Artists Whose Friendship & Work Began in Paris During the 1880s, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1976.

- Susan Martis, "Famous and Forgotten: Rodin and Three Contemporaries," Ph.D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 2004.

- Frederick C. Moffatt, Errant Bronzes: George Grey Barnard's Statues of Abraham Lincoln, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1998.

- "The George Grey Banard Collection," Philadelphia Museum Bulletin 40, no. 206 (1945): [49]–[64].

- Robinson Galleries, The George Grey Barnard Collection, New York: The Galleries, 1941.

- Nicholas Fox Weber, The Clarks of Cooperstown: Their Singer Sewing Machine Fortune, Their Great and Influential Art Collections, Their Forty-Year Feud, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Grey Barnard. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Barnard, George Grey. |

- George Grey Barnard Exhibit – Kankakee County Historical Society (scroll down)

- George Grey Barnard Papers – Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Centre County Historical Society

- George Grey Barnard at Find a Grave

- The George Grey Barnard Papers: 1889-1967 from the Cloisters Library and Archives, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.