Frictionless plane

The frictionless plane is a concept from the writings of Galileo Galilei. In his 1608 The Two New Sciences, Galileo presented a formula that predicted the motion of an object moving down an inclined plane. His formula was based upon his past experimentation with free-falling bodies.[1] However, his model was not based upon experimentation with objects moving down an inclined plane, but from his conceptual modeling of the forces acting upon the object. Galileo understood the mechanics of the inclined plane as the combination of horizontal and vertical vectors; the result of gravity acting upon the object, diverted by the slope of the plane.[2]

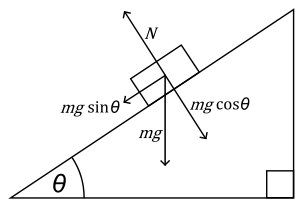

N = normal force that is perpendicular to the plane

m = mass of object

g = acceleration due to gravity

θ (theta) = angle of elevation of the plane, measured from the horizontal

However, Galileo's equations do not contemplate friction, and therefore do not perfectly predict the results of an actual experiment. This is because some energy is always lost when one mass applies a non-zero normal force to another. Therefore, the observed speed, acceleration and distance traveled should be less than Galileo predicts.[3] This energy is lost in forms like sound and heat. However, from Galileo's predictions of an object moving down an inclined plane in a frictionless environment, he created the theoretical foundation for extremely fruitful real-world experimental prediction.[4]

Frictionless planes do not exist in the real world. However, if they did, one can be almost certain that objects on them would behave exactly as Galileo predicts. Despite their nonexistence, they have considerable value in the design of engines, motors, roadways, and even tow-truck beds, to name a few examples.[5]

The effect of friction on an object moving down an inclined plane can be calculated as

where is the force of friction exerted by the object and the inclined plane on each other, parallel to the surface of the plane, is the normal force exerted by the object and the plane on each other, directed perpendicular to the plane, and is the coefficient of kinetic friction.[6]

Unless the inclined plane is in a vacuum, a (usually) small amount of potential energy is also lost to air drag.

See also

References

- Drake, Stillman, Galileo’s Experimental Confirmation of Horizontal Inertia: Unpublished Manuscripts. Isis: Vol. 64, No. 3, p. 296.

- Settle, T. B. "An Experiment in the History of Science", Science, 1061 133 19–23.

- Jenkin, Fleeming. On Friction Between Surfaces at Low Speeds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 26 p. 93–94

- Drake, at p. 297–99

- Koyré, Alexandre Metaphysics and Measurement, pp. 83–84 (1992).

- Koyré, pp. 84–86.