France–United Kingdom relations

France–United Kingdom relations are the relations between the governments of the French Republic and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK). The historical ties between France and the UK, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas, except Scotland and Northern Ireland, conquered by Rome, whose fortifications exist in both countries to this day, and whose writing system introduced a common alphabet to both areas; however, the language barrier remained. The Norman conquest of England in 1066 decisively shaped English history, as well as the English language. In the Middle Ages, France and England were often bitter enemies, with both nations' monarchs claiming control over France, while Scotland was usually allied with France until the Union of the Crowns. Some of the noteworthy conflicts include the Hundred Years' War and the French Revolutionary Wars which were French victories, as well as the Seven Years' War and Napoleonic Wars, from which Great Britain emerged victorious.

| |

United Kingdom |

France |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of the United Kingdom, Paris | Embassy of France, London |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Edward Llewellyn | Ambassador Catherine Colonna |

The last major conflict between the two were the Napoleonic Wars in which coalitions of European powers, financed and usually led by the United Kingdom fought a series of wars against the First French Empire and its client states, culminating in the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. There were some subsequent tensions, especially after 1880, over such issues as the Suez Canal and rivalry for African colonies. Despite some brief war scares, peace always prevailed. Friendly ties between the two began with the 1904 Entente Cordiale, and the British and French were allied against Germany in both World War I and World War II; in the latter conflict, British armies helped to liberate occupied France from the Nazis. Both nations opposed the Soviet Union during the Cold War and were founding members of NATO, the Western military alliance led by the United States. During the 1960s, French President Charles de Gaulle distrusted the British for being too close to the Americans, and for years he blocked British entry into the European Economic Community, now called the European Union. De Gaulle also pulled France out of its active role in NATO because that alliance was too heavily dominated by Washington. After his death, Britain did enter the European Economic Community and France returned to NATO.

In recent years the two countries have experienced a quite close relationship, especially on defence and foreign policy issues; the two countries tend, however, to disagree on a range of other matters, most notably the European Union.[1] France and Britain are often still referred to as "historic rivals"[2] or with emphasis on the perceived ever-lasting competition that still opposes the two countries.[3] French author José-Alain Fralon characterised the relationship between the countries by describing the British as "our most dear enemies".

Unlike France, the United Kingdom left the European Union in 2020, after it voted to do so in a referendum held on 23 June 2016.[4] It is estimated that about 350,000 French people live in the UK, with approximately 400,000 Britons living in France.[5]

Country comparison

| France | United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|

| Flag |  |

|

| Coat of Arms |  |

|

| Population | 67,800,000 | 67,530,172 |

| Area | 674,843 km2 (260,558 sq mi) | 243,610 km2 (94,060 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 116/km2 (301/sq mi) | 255.6/km2 (661.9/sq mi) |

| Time zones | 12 | 9 |

| Exclusive economic zone | 11,691,000 km2 | 6,805,586 km2 |

| Capital | Paris | London |

| Largest City | Paris – 2,187,526 (10,900,952 Urban) | London – 8,908,081 (9,046,485 Urban) |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Head of State | President: Emmanuel Macron | Monarch: Elizabeth II |

| Head of Government | Prime Minister: Jean Castex | Prime Minister: Boris Johnson |

| Legislature | Parliament | Parliament |

| Upper House | Senate President: Gérard Larcher |

House of Lords Lord Speaker: The Lord Fowler |

| Lower House | National Assembly President: Richard Ferrand |

House of Commons Speaker: Sir Lindsay Hoyle |

| Official language | French (de facto and de jure) | English (de facto) |

| Main religions | 60.5% Christianity (57% Catholic, 3% Protestant), 35% Non-Religious, 3.5% other faiths, 1% Unanswered[6] | 59.4% Christianity, 25.7% Non-Religious, 7.8% Unstated, 4.4% Islam, 1.3% Hinduism, 0.7% Sikhism, 0.4% Judaism, 0.4% Buddhism (2011 Census) |

| Ethnic groups | 89.7% French, 7% other European, 3.3% North African, Other Sub-Saharan African, Indochinese, Asian, Latin American and Pacific Islander. | 87% White (81.9% White British), 7% Asian British (2.3% Indian, 1.9% Pakistani, 0.7% Bangladeshi, 0.7% Chinese, 1.4% Asian Other) 3% Black 2% Mixed Race. (2011 census) |

| GDP (per capita) | $41,760 | $48,112 |

| GDP (per capita) | $48,640 | $58,760 |

| GDP (nominal) | $2,771 trillion | $2,912 trillion |

| Expatriate populations | 350,000 French-born people live in the UK (2017 data)[7] | 400,000 British-born people live in France (2017 data)[8] |

| Military expenditures | $50.1 billion | $55.0 billion |

| Nuclear warheads active/total | 290 / 300 | 120 / 200 |

History

Roman and post-Roman era

When Julius Caesar invaded Gaul, he encountered allies of the Gauls and Belgae from southeastern Britain offering assistance, some of whom even acknowledged the king of the Belgae as their sovereign.

Although all the peoples concerned were Celts (as the Germanic Angles and Franks had not yet invaded either country that would later bear their names), this could arguably be seen as the first major example of Anglo-French co-operation in recorded history. As a consequence, Caesar felt compelled to invade, in an attempt to subdue Britain. Rome was reasonably successful at conquering Gaul, Britain and Belgica; and all three areas became provinces of the Roman Empire.

For the next five hundred years, there was much interaction between the two regions, as both Britain and France were under Roman rule. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, this was followed by another five hundred years with very little interaction between the two, as both were invaded by different Germanic tribes. Anglo-Saxonism rose from a mixture of Brythonism and Scandinavian immigration in Britain to conquer the Picts and Gaels. France saw intermixture with and partial conquest by Germanic tribes such as the Salian Franks to create the Frankish kingdoms. Christianity as a religion spread through all areas involved during this period, replacing the Germanic, Celtic and pre-Celtic forms of worship. The deeds of chieftains in this period would produce the legendaria around King Arthur and Camelot – now believed to be a legend based on the deeds of many early medieval British chieftains – and the more historically verifiable Charlemagne, the Frankish chieftain who founded the Holy Roman Empire throughout much of Western Europe. At the turn of the second millennium, the British Isles were primarily involved with the Scandinavian world, while France's main foreign relationship was with the Holy Roman Empire.[9]

Before the Conquest

Prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066, there were no armed conflicts between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France. France and England were subject to repeated Viking invasions, and their foreign preoccupations were primarily directed toward Scandinavia.

Such cross-Channel relations as England had were directed toward Normandy, a quasi-independent fief owing homage to the French king; Emma, daughter of Normandy's Duke Richard, became queen to two English kings in succession; two of her sons, Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor later became kings of England. Edward spent much of his early life (1013–1041) in Normandy and, as king, favored certain Normans with high office, such as Robert of Jumièges, who became Archbishop of Canterbury.

This gradual Normanization of the realm set the stage for the Norman Conquest, in which Emma's brother's grandson, William, Duke of Normandy, gained the kingdom in the first successful cross-Channel invasion since Roman times. Together with its new ruler, England acquired the foreign policy of the Norman dukes, which was based on protecting and expanding Norman interests at the expense of the French kings. Although William's rule over Normandy had initially had the backing of King Henry I of France, William's success had soon created hostility, and in 1054 and 1057 King Henry had twice attacked Normandy.

Norman conquest

However, in the mid-eleventh century there was a dispute over the English throne, and the French-speaking Normans, who were of Viking, Frankish, and Gallo-Roman stock, invaded England under their duke William the Conqueror and took over following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and crowned themselves Kings of England. The Normans took control of the land and the political system. Feudal culture took root in England, and for the next 150 years England was generally considered of secondary importance to the dynasty's Continental territories, notably in Normandy and other western French provinces. The language of the aristocracy was French for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest. Many French words were adopted into the English language as a result. About one third of the English language is derived from or through various forms of French. The first Norman kings were also the Dukes of Normandy, so relations were somewhat complicated between the countries. Though they were dukes ostensibly under the king of France, their higher level of organisation in Normandy gave them more de facto power. In addition, they were kings of England in their own right; England was not officially a province of France, nor a province of Normandy.[10]

Breton War, 1076–1077

This war was fought between the years 1076 to 1077.[11]

Vexin War, 1087

In 1087, following the monastic retirement of its last count, William and Philip partitioned between themselves the Vexin, a small but strategically important county on the middle Seine that controlled the traffic between Paris and Rouen, the French and Norman capitals. With this buffer state eliminated, Normandy and the king's royal demesne (the Île-de-France) now directly bordered on each other, and the region would be the flashpoint for several future wars. In 1087, William responded to border raids conducted by Philip's soldiers by attacking the town of Mantes, during the sack of which he received an accidental injury that turned fatal.

Rebellion of 1088

With William's death, his realms were parted between his two sons (England to William Rufus, Normandy to Robert Curthose) and the Norman-French border war concluded. Factional strains between the Norman barons, faced with a double loyalty to William's two sons, created a brief civil war in which an attempt was made to force Rufus off the English throne. With the failure of the rebellion, England and Normandy were clearly divided for the first time since 1066.

Wars in the Vexin and Maine, 1097–1098

Robert Curthose left on crusade in 1096, and for the duration of his absence Rufus took over the administration of Normandy. Soon afterwards (1097) he attacked the Vexin and the next year the County of Maine. Rufus succeeded in defeating Maine, but the war in the Vexin ended inconclusively with a truce in 1098.[12]

Anglo-Norman War, 1101

In August 1100, William Rufus was killed by an arrow shot while hunting. His younger brother, Henry Beauclerc immediately took the throne. It had been expected to go to Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, but Robert was away on a crusade and did not return until a month after Rufus' death, by which time Henry was firmly in control of England, and his accession had been recognized by France's King Philip. Robert was, however, able to reassert his control over Normandy, though only after giving up the County of Maine.

England and Normandy were now in the hands of the two brothers, Henry and Robert. In July 1101, Robert launched an attack on England from Normandy. He landed successfully at Portsmouth, and advanced inland to Alton in Hampshire. There he and Henry came to an agreement to accept the status quo of the territorial division. Henry was freed from his homage to Robert, and agreed to pay the Duke an annual sum (which, however, he only paid until 1103).[13]

Anglo-Norman War, 1105–1106

Following increasing tensions between the brothers, and evidence of the weakness of Robert's rule, Henry I invaded Normandy in the spring of 1105, landing at Barfleur. The ensuing Anglo-Norman war was longer and more destructive, involving sieges of Bayeux and Caen; but Henry had to return to England in the late summer, and it was not until the following summer that he was able to resume the conquest of Normandy. In the interim, Duke Robert took the opportunity to appeal to his liege lord, King Philip, but could obtain no aid from him. The fate of Robert and the duchy was sealed at the Battle of Tinchebray on 28 or 29 September 1106: Robert was captured and imprisoned for the rest of his life. Henry was now, like his father, both King of England and Duke of Normandy, and the stage was set for a new round of conflict between England and France.

Anglo-French War, 1117–1120

In 1108, Philip I, who had been king of France since before the Norman Conquest, died and was succeeded by his son Louis VI, who had already been conducting the administration of the realm in his father's name for several years.

Louis had initially been hostile to Robert Curthose, and friendly to Henry I; but with Henry's acquisition of Normandy, the old Norman-French rivalries re-emerged. From 1109 to 1113, clashes erupted in the Vexin; and in 1117 Louis made a pact with Baldwin VII of Flanders, Fulk V of Anjou, and various rebellious Norman barons to overthrow Henry's rule in Normandy and replace him with William Clito, Curthose's son. By luck and diplomacy, however, Henry eliminated the Flemings and Angevins from the war, and on 20 August 1119 at the Battle of Bremule he defeated the French. Louis was obliged to accept Henry's rule in Normandy, and accepted his son William Adelin's homage for the fief in 1120.

High Middle Ages

During the reign of the closely related Plantagenet dynasty, which was based in its Angevin Empire, and at the height of the empires size, 1/3 of France was under Angevin control as well as all of England. However, almost all of the Angevin empire was lost to Philip II of France under Richard the Lionheart, John and Henry III of England. This finally gave the English a separate identity as an Anglo-Saxon people under a Francophone, but not French, crown.[15]

While the English and French had been frequently acrimonious, they had always had a common culture and little fundamental difference in identity. Nationalism had been minimal in days when most wars took place between rival feudal lords on a sub-national scale. The last attempt to unite the two cultures under such lines was probably a failed French-supported rebellion to depose Edward II. It was also during the Middle Ages that a Franco-Scottish alliance, known as the Auld Alliance was signed by King John of Scotland and Philip IV of France.[16]

The Hundred Years' War

The English monarchy increasingly integrated with its subjects and turned to the English language wholeheartedly during the Hundred Years' War between 1337 and 1453. Though the war was in principle a mere dispute over territory, it drastically changed societies on both sides of the Channel. The English, although already politically united, for the first time found pride in their language and identity, while the French united politically.[17][18]

Several of the most famous Anglo-French battles took place during the Hundred Years' War: Crécy, Poitiers, Agincourt, Orléans, Patay, Formigny and Castillon. Major sources of French pride stemmed from their leadership during the war. Bertrand du Guesclin was a brilliant tactician who forced the English out of the lands they had procured at the Treaty of Brétigny, a compromising treaty that most Frenchmen saw as a humiliation. Joan of Arc was another unifying figure who to this day represents a combination of religious fervour and French patriotism to all France. After her inspirational victory at Orléans and what many saw as Joan's martyrdom at the hands of Burgundians and Englishmen, Jean de Dunois eventually forced the English out of all of France except Calais, which was only lost in 1558. Apart from setting national identities, the Hundred Years' War was the root of the traditional rivalry and at times hatred between the two countries. During this era, the English lost their last territories in France, except Calais, which would remain in English hands for another 105 years, though the English monarchs continued to style themselves as Kings of France until 1800.[19]

The Franco-Scots Alliance

France and Scotland agreed to defend each other in the event of an attack on either from England in several treaties, the most notable of which were in 1327 and 1490. There had always been intermarriage between the Scottish and French royal households, but this solidified the bond between the royals even further.[20] Scottish historian J. B. Black took a critical view, arguing regarding the alliance:

- The Scots...love for their 'auld' ally had never been a positive sentiment nourished by community of culture, but an artificially created affection resting on the negative basis of enmity to England.[21]

The early modern period

The English and French were engaged in numerous wars in the following centuries. They took opposite sides in all of the Italian Wars between 1494 and 1559.

An even deeper division set in during the English Reformation, when most of England converted to Protestantism and France remained Roman Catholic. This enabled each side to see the other as not only a foreign evil but also a heretical one. In both countries there was intense civil religious conflict. Because of the oppression by Roman Catholic King Louis XIII of France, many Protestant Huguenots fled to England. Similarly, many Catholics fled from England to France. Scotland had a very close relationship with France in the 16th century, with intermarriage at the highest level.

Henry VIII of England had initially sought an alliance with France, and the Field of the Cloth of Gold saw a face to face meeting between him and King Francis I of France. Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) Was born to King James V and his French second wife, Mary of Guise and became Queen when her father was killed in the wars with England. Her mother became Regent, brought in French advisors, and ruled Scotland in the French style. David Ditchburn and Alastair MacDonald argue:

- Protestantism was, however, given an enormous boost in Scotland, especially among the governing classes, by the suffocating political embrace of Catholic France. The threat to Scotland's independence seem to come most potently from France, not England... And absorption by France was not a future that appealed to Scots.[22]

Queen Elizabeth I, whose own legitimacy was challenged by Mary Queen of Scots, worked with the Protestant Scottish Lords to expel the French from Scotland in 1560.[23] The Treaty of Edinburgh in 1560 virtually ended the "auld alliance." Protestant Scotland tied its future to Protestant England, rejecting Catholic France. However, friendly relations at the business level did continue.[24]

Universal Monarchy

.png.webp)

While Spain had been the dominant world power in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the English had often sided with France as a counterweight against them.[25] This design was intended to keep a European balance of power, and prevent one country gaining overwhelming supremacy. Key to English strategy was the fear that a universal monarchy of Europe would be able to overwhelm the British Isles.[26]

At the conclusion of the English Civil War, the newly formed Republic under Oliver Cromwell, "the Commonwealth of England" joined sides with the French against Spain during the last decade of the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659). The English were particularly interested in the troublesome city of Dunkirk and in accordance with the alliance the city was given to the English after the Battle of the Dunes (1658), but after the monarchy was restored in England, Charles II sold it back to the French in 1662 for £320,000.

Following the conclusion of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, and as France finally overcame its rebellious "princes of the blood" and Protestant Huguenots, the long fought wars of the Fronde (civil wars) finally came to an end. At the same time Spain's power was severely weakened by decades of wars and rebellions – and France, began to take on a more assertive role under King Louis XIV of France with an expansionist policy both in Europe and across the globe. English foreign policy was now directed towards preventing France gaining supremacy on the continent and creating a universal monarchy. To the French, England was an isolated and piratical nation heavily reliant on naval power, and particularly privateers, which they referred to as Perfidious Albion.

However, in 1672, the English again formed an alliance with the French (in accordance with the Secret Treaty of Dover of 1670) against their common commercial rival, the rich Dutch Republic – the two nations fighting side by side during the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) and Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674). This war was extremely unpopular in England. The English had been soundly beaten at sea by the Dutch and were in a worsening financial situation as their vulnerable global trade was under increasing threat. The English pulled out of the alliance in 1674, ending their war with the Netherlands and actually joining them against the French in the final year of the Franco-Dutch War in 1678.

During the course of the century a sharp diversion in political philosophies emerged in the two states. In England King Charles I had been executed during the English Civil War for exceeding his powers, and later King James II had been overthrown in the Glorious Revolution. In France, the decades long Fronde (civil wars), had seen the French Monarchy triumphant and as a result the power of the monarchs and their advisors became almost absolute and went largely unchecked.

England and France fought each other in the War of the League of Augsburg from 1688 to 1697 which set the pattern for relations between France and Great Britain during the eighteenth century. Wars were fought intermittently, with each nation part of a constantly shifting pattern of alliances known as the stately quadrille.

Second Hundred Years' War 1689–1815

18th century

.svg.png.webp)

Partly out of fear of a continental intervention, an Act of Union was passed in 1707 creating the Kingdom of Great Britain, and formally merging the kingdoms of Scotland and England (the latter kingdom included Wales).[27] While the new Britain grew increasingly parliamentarian, France continued its system of absolute monarchy.[28]

The newly united Britain fought France in the War of the Spanish Succession from 1702 to 1713, and the War of the Austrian Succession from 1740 to 1748, attempting to maintain the balance of power in Europe. The British had a massive navy but maintained a small land army, so Britain always acted on the continent in alliance with other states such as Prussia and Austria as they were unable to fight France alone. Equally France, lacking a superior navy, was unable to launch a successful invasion of Britain.[29]

France lent support to the Jacobite pretenders who claimed the British throne, hoping that a restored Jacobite monarchy would be inclined to be more pro-French. Despite this support the Jacobites failed to overthrow the Hanoverian monarchs.[30]

The quarter century after the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 was peaceful, with no major wars, and only a few secondary military episodes of minor importance. The main powers had exhausted themselves in warfare, with many deaths, disabled veterans, ruined navies, high pension costs, heavy loans and high taxes. Utrecht strengthened the sense of useful international law and inaugurated an era of relative stability in the European state system, based on balance-of-power politics that no one country would become dominant.[31] Robert Walpole, the key British policy maker, prioritized peace in Europe because it was good for his trading nation and its growing British Empire. British historian G. M. Trevelyan argues:

- That Treaty [of Utrecht], which ushered in the stable and characteristic period of Eighteenth-Century civilization, marked the end of danger to Europe from the old French monarchy, and it marked a change of no less significance to the world at large, — the maritime, commercial and financial supremacy of Great Britain.[32]

But "balance" needed armed enforcement. Britain played a key military role as "balancer." The goals were to bolster Europe's balance of power system to maintain peace that was needed for British trade to flourish and its colonies to grow, and finally to strengthen its own central position in the balance of power system in which no one could dominate the rest. Other nations recognized Britain as the "balancer." Eventually the balancing act required Britain to contain French ambitions. Containment led to a series of increasingly large-scale wars between Britain and France, which ended with mixed results. Britain was usually aligned with the Netherlands and Prussia, and subsidised their armies. These wars enveloped all of Europe and the overseas colonies. These wars took place in every decade starting in the 1740s and climaxed in the defeat of Napoleon's France in 1814.[33]

As the century wore on, there was a distinct passage of power to Britain and France, at the expense of traditional major powers such as Portugal, Spain and the Dutch Republic. Some observers saw the frequent conflicts between the two states during the 18th century as a battle for control of Europe, though most of these wars ended without a conclusive victory for either side. France largely had greater influence on the continent while Britain were dominant at sea and trade, threatening French colonies abroad.[34]

Overseas expansion

From the 1650s, the New World increasingly became a battleground between the two powers. The Western Design of Oliver Cromwell intended to build up an increasing British presence in North America, beginning with the acquisition of Jamaica from the Spanish Empire in 1652.[35] The first British settlement on continental North America was founded in 1607, and by the 1730s these had grown into thirteen separate colonies.

The French had settled the province of Canada to the North, and controlled Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean, the wealthiest colony in the world.[36] Both countries, recognizing the potential of India, established trading posts there. Wars between the two states increasingly took place in these other continents, as well as Europe.

Seven Years' War

The French and British fought each other and made treaties with Native American tribes to gain control of North America. Both nations coveted the Ohio Country and in 1753 a British expedition there led by George Washington clashed with a French force. Shortly afterwards the French and Indian War broke out, initially taking place only in North America but in 1756 becoming part of the wider Seven Years' War in which Britain and France were part of opposing coalitions.

The war has been called the first "world war", because fighting took place on several different continents.[37] In 1759 the British enjoyed victories over the French in Europe, Canada and India, severely weakening the French position around the world.[38] In 1762 the British captured the cities of Manila and Havana from Spain, France's strongest ally, which led ultimately to a peace settlement the following year that saw a large number of territories come under British control.

The Seven Years' War is regarded as a critical moment in the history of Anglo-French relations, which laid the foundations for the dominance of the British Empire during the next two and a half centuries.

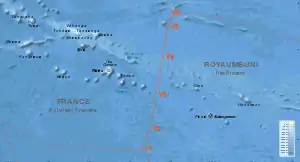

South Seas

Having lost New France (Canada) and India in the northern hemisphere, many Frenchmen turned their attention to building a second empire south of the equator, thereby triggering a race for the Pacific Ocean. They were supported by King Louis XV and by the Duc de Choiseul, Minister for War and for the Navy. In 1763, Louis Bougainville sailed from France with two ships, several families, cattle, horses and grain. He established the first colony in the Falkland Islands at Port Saint Louis in February 1764. This done, Bougainville's plan was to use the new settlement as a French base from where he could mount a search for the long-imagined (but still undiscovered) Southern Continent and claim it for France.[39]

Meanwhile, the Secretary of the Admiralty, Philip Stephens, swiftly and secretly dispatched John Byron to the Falklands and round the world. He was followed in 1766 by Samuel Wallis who discovered Tahiti and claimed it for Britain. Bougainville followed and claimed Tahiti for France in 1768, but when he tried to reach the east coast of New Holland (Australia), he was thwarted by the Great Barrier Reef.[40]

The Admiralty sent Captain Cook to the Pacific on three voyages of discovery in 1768, 1772 and 1776. Cook was killed in Hawaii in 1779 and his two ships, Resolution and Discovery, arrived home in October 1780.

At the same time, more Frenchmen were probing the South Seas. In 1769, Jean Surville sailed from India, through the Coral Sea to New Zealand then traversed the Pacific to Peru. In 1771, Marion Dufresne and Julien–Marie Crozet sailed through the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Later in 1771, another French expedition under Yves de Kerguelen and Louis St Aloüarn explored the southern Indian Ocean. St Aloüarn annexed the west coast of New Holland for France in March 1772.

In August 1785, King Louis XVI sent Jean-François Lapérouse to explore the Pacific Ocean. He arrived off Sydney Heads in January 1788, three days after the arrival of Britain's First Fleet commanded by Arthur Phillip. The French expedition departed Australia three months later in March 1788 and, according to the records, was never seen again.

The race for territory in the South Seas continued into the nineteenth century. Although the British had settled the eastern region of New Holland, in 1800 Napoleon dispatched an expedition commanded by Nicolas Baudin to forestall the British on the south and west coasts of the continent.[41]

American War of Independence

As American Patriot dissatisfaction with British policies grew to rebellion in 1774–75, the French saw an opportunity to undermine British power. When the American War of Independence broke out in 1775, the French began sending covert supplies and intelligence to the American rebels.[42]

In 1778, France, hoping to capitalise on the British defeat at Saratoga, recognized the United States of America as an independent nation. Negotiating with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, they formed a military alliance.[43] France in 1779 persuaded its Spanish allies to declare war on Britain.[44] France despatched troops to fight alongside the Americans, and besieged Gibraltar with Spain. Plans were drawn up, but never put into action, to launch an invasion of England. The threat forced Britain to keep many troops in Britain that were needed in America. The British were further required to withdraw forces from the American mainland to protect their more valuable possessions in the West Indies. While the French were initially unable to break the string of British victories, the combined actions of American and French forces, and a key victory by a French fleet over a British rescue fleet, forced the British into a decisive surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781.[45] For a brief period after 1781 Britain's naval superiority was threatened subdued by an alliance between France and Spain. However, the British recovered, defeated the main French fleet in April 1782, and kept control of Gibraltar.[46] In 1783 the Treaty of Paris gave the new nation control over most of the region east of the Mississippi River; Spain gained Florida from Britain and retained control of the vast Louisiana Territory; France received little except a huge debt.[47]

The crippling debts incurred by France during the war, and the cost of rebuilding the French navy during the 1780s caused a financial crisis, helping contribute to the French Revolution of 1789.[48]

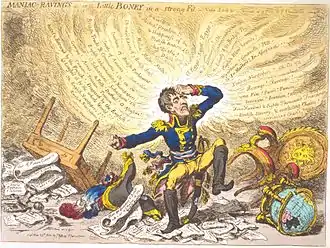

The French Revolution and Napoleon

During the French Revolution, the anti-monarchical ideals of France were regarded with alarm throughout Europe. While France was plunged into chaos, Britain took advantage of its temporary weakness to stir up the civil war occurring in France and build up its naval forces. The Revolution was initially popular with many Britons, both because it appeared to weaken France and was perceived to be based on British liberal ideals. This began to change as the Jacobin faction took over, and began the Reign of Terror (or simply the Terror, for short).[49]

The French were intent on spreading their revolutionary republicanism to other European states, including Britain. The British initially stayed out of the alliances of European states which unsuccessfully attacked France trying to restore the monarchy. In France a new, strong nationalism took hold enabling them to mobilise large and motivated forces. Following the execution of King Louis XVI of France in 1793, France declared war on Britain. This period of the French Revolutionary Wars was known as the War of the First Coalition. Except for a brief pause in 1802–03, the wars lasted continuously for 21 years. During this time Britain raised several coalitions against the French, continually subsidising other European states with the Golden Cavalry of St George, enabling them to put large armies in the field. In spite of this, the French armies were very successful on land, creating several client states such as the Batavian Republic, and the British devoted much of their own forces to campaigns against the French in the Caribbean, with mixed results.[50][51]

Ireland

In 1798 French forces invaded Ireland to assist the United Irishmen who had launched a rebellion, where they were joined by thousands of rebels but were defeated by British and Irish loyalist forces. The fear of further attempts to create a French satellite in Ireland led to the Act of Union, merging the Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland to create the United Kingdom in 1801. Ireland now lost its last vestiges of independence.[52]

First phase, 1792 to 1802

Following the execution of King Louis XVI of France in 1793, France declared war on Britain. This period of the French Revolutionary Wars was known as the War of the First Coalition, which lasted from 1792 to 1797.

The British policy at the time was to give financial and diplomatic support to their continental allies, who did nearly all of the actual fighting on land. France meanwhile set up the conscription system that built up a much larger army than anyone else. After the king was executed, nearly all the senior officers went into exile, and a very young new generation of officers, typified by Napoleon, took over the French military. Britain relied heavily on the Royal Navy, which sank the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, trapping the French army in Egypt. In 1799, Napoleon came to power in France, and created a dictatorship. Britain led the Second Coalition from 1798 to 1802 against Napoleon, but he generally prevailed. The Treaty of Amiens of 1802 was favorable to France. That treaty amounted to a year-long truce in the war, which was reopened by Britain in May 1803.

Britain ended the uneasy truce created by the Treaty of Amiens when it declared war on France in May 1803, thus starting the War of the Third Coalition, lasting from 1803 to 1805. The British were increasingly angered by Napoleon's reordering of the international system in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands. Kagan[54] argues that Britain was insulted and alarmed especially by Napoleon's assertion of control over Switzerland. Britons felt insulted when Napoleon said it deserved no voice in European affairs (even though King George was an elector of the Holy Roman Empire), and ought to shut down the London newspapers that were vilifying Napoleon. Russia, furthermore, decided that the Switzerland intervention indicated that Napoleon was not looking toward a peaceful resolution.[55] Britain had a sense of loss of control, as well as loss of markets, and was worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. McLynn argues that Britain went to war in 1803 out of a "mixture of economic motives and national neuroses – an irrational anxiety about Napoleon's motives and intentions." However, in the end it proved to be the right choice for Britain, because in the long run Napoleon's intentions were hostile to British national interest. Furthermore, Napoleon was not ready for war and this was the best time for Britain to stop them.[56] Britain therefore seized upon the Malta issue (by refusing to follow the terms of the Treaty of Amiens and evacuate the island).

The deeper British grievances were that Napoleon was taking personal control of Europe, making the international system unstable, and forcing Britain to the sidelines.[57][58][59][60]

War resumes, 1803–1815

After he had triumphed on the European continent against the other major European powers, Napoleon contemplated an invasion of the British mainland. That plan collapsed after the annihilation of the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar, coinciding with an Austrian attack over its Bavarian allies.

In response Napoleon established a continental system by which no nation was permitted to trade with the British. Napoleon hoped the embargo would isolate the British Isles severely weakening them, but a number of countries continued to trade with them in defiance of the policy. In spite of this, the Napoleonic influence stretched across much of Europe.

In 1808 French forces invaded Portugal trying to attempt to halt trade with Britain, turning Spain into a satellite state in the process.[61] The British responded by dispatching a force under Sir Arthur Wellesley which captured Lisbon.[62] Napoleon dispatched increasing forces into the Iberian Peninsula, which became the key battleground between the two nations. Allied with Spanish and Portuguese forces, the British inflicted a number of defeats on the French, confronted with a new kind of warfare called "guerrilla" which led Napoleon to brand it the "Spanish Ulcer".

In 1812, Napoleon's invasion of Russia caused a new coalition to form against him, in what became the War of the Sixth Coalition.In 1813, British forces defeated French forces in Spain and caused them to retreat into France. Allied to an increasingly resurgent European coalition, the British invaded southern France in October 1813, forcing Napoleon to abdicate and go into exile on Elba in 1814.[63]

Napoleon was defeated by combined British, Prussian and Dutch forces at Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. With strong British support, the Bourbon monarchy was restored and Louis XVIII was crowned King of France. The Napoleonic era was the last occasion on which Britain and France went to war with each other, but by no means marked the end of the rivalry between the two nations. Viscount Castlereagh shaped British foreign policy as foreign minister 1812–1822; he led the moves against Napoleon 1812 and 1815. Once the Bourbon allies were back in power he established a partnership with France during the Congress of Vienna.[64]

Long 19th century: 1789–1914

Britain and France never went to war after 1815, although there were a few "war scares." They were allied together against Russia in the Crimean War of the 1850s.

1815–1830

Despite having entered the Napoleonic era regarded by many as a spent force, Britain had emerged from the 1815 Congress of Vienna as the ultimate leading financial, military and cultural power of the world, going on to enjoy a century of global dominance in the Pax Britannica.[65] France also recovered from the defeats to retake its position on the world stage. Talleyrand's friendly approaches were a precursor to the Entente Cordiale in the next century, but they lacked consistent direction and substance.[66] Overcoming their historic enmity, the British and French eventually became political allies, as both began to turn their attentions to acquiring new territories beyond Europe. The British developed India and Canada and colonized Australia, spreading their powers to several different continents as the Second British Empire. Likewise the French were quite active in Southeast Asia and Africa.

They frequently made stereotypical jokes about each other, and even side by side in war were critical of each other's tactics. As a Royal Navy officer said to the French corsair Robert Surcouf "You French fight for money, while we British fight for honour.", Surcouf replied "Sir, a man fights for what he lacks the most." According to one story, a French diplomat once said to Lord Palmerston "If I were not a Frenchman, I should wish to be an Englishman"; to which Palmerston replied: "If I were not an Englishman, I should wish to be an Englishman."[67] According to another, upon seeing the disastrous British Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War against Russia, French marshal Pierre Bosquet said 'C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre.' ('It's magnificent, but it's not war.') Eventually, relations settled down as the two empires tried to consolidate themselves rather than extend themselves.

July Monarchy and the beginning of the Victorian age

In 1830, France underwent the July Revolution, and the Orléanist Louis-Philippe subsequently ascended to the throne; by contrast, the reign of Queen Victoria began in 1837 in a much more peaceful fashion. The major European powers—Russia, Austria, Britain, and to some extent Prussia—were determined to keep France in check, and so France generally pursued a cautious foreign policy. Louis-Phillipe allied with Britain, the country with which France shared the most similar form of government, and its combative Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston. In Louis-Philippe's first year in power, he refused to annex Belgium during its revolution, instead following the British line of supporting independence. Despite posturings from leading French minister Adolphe Thiers in 1839–1840 that France would protect the increasingly powerful Muhammad Ali of Egypt (a viceroy of the Ottoman Empire), any reinforcements were not forthcoming, and in 1840, much to France's embarrassment, Ali was forced to sign the Convention of London by the powers. Relations cooled again under the governments of François Guizot and Robert Peel. They soured once more in 1846 though when, with Palmerston back as Foreign Secretary, the French government hastily agreed to have Isabella II of Spain and her sister marry members of the Bourbon and Orléanist dynasties, respectively. Palmerston had hoped to arrange a marriage, and "The Affair of the Spanish Marriages" has generally been viewed unfavourably by British historians ("By the dispassionate judgment of history it has been universally condemned"),[68] although a more sympathetic view has been taken in recent years.[69]

Second French Empire

Lord Aberdeen (foreign secretary 1841–46) brokered an Entente Cordiale with François Guizot and France in the early 1840s. However Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president of France in 1848 and made himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1851. Napoleon III had an expansionist foreign policy, which saw the French deepen the colonisation of Africa and establish new colonies, in particular Indochina. The British were initially alarmed, and commissioned a series of forts in southern England designed to resist a French invasion. Lord Palmerston as foreign minister and prime minister had close personal ties with leading French statesmen, notably Napoleon III himself. Palmerston's goal was to arrange peaceful relations with France in order to free Britain's diplomatic hand elsewhere in the world.[70]

Napoleon at first had a pro-British foreign policy, and was eager not to displease the British government whose friendship he saw as important to France. After a brief threat of an invasion of Britain in 1851, France and Britain cooperated in the 1850s, with an alliance in the Crimean War , and a major trade treaty in 1860. The Cobden–Chevalier Treaty Of 1860 lowered tariffs in each direction, and began the British practice of encouraging lower tariffs across Europe, and using most favored nation treaties. However Britain viewed the Second Empire with increasing distrust, especially as the emperor built up his navy, expanded his empire and took up a more active foreign policy.[71]

The two nations were military allies during the Crimean War (1853–56) to curb Russia's expansion westwards and its threats to the Ottoman Empire. However, when London discovered that Napoleon III was secretly negotiating with Russia to form a postwar alliance to dominate Europe, it hastily abandoned its plan to end the war by attacking St. Petersburg. Instead Britain concluded an armistice with Russia that achieved none of its war aims.[72][73]

There was a brief war scare in 1858-1860 as alarmists in England misinterpreted scattered hints as signs of an invasion, but Napoleon III never planned any such hostility.[74] The two nations co-operated during the Second Opium War with China, dispatching a joint force to the Chinese capital Peking to force a treaty on the Chinese Qing Dynasty. In 1859 Napoleon, bypassing the Corps législatif which he feared would not approve of free trade, met with influential reformer Richard Cobden, and in 1860 the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty was signed between the two countries, reducing tariffs on goods sold between Britain and France.[75]

During the American Civil War (1861-1865) both nations considered intervention to help the Confederacy and thereby regain cotton supplies, but remained neutral. The cutoff of cotton shipments caused economic depression in the textile industries of both Britain and France, resulting in widespread unemployment and suffering among workers. In the end France dared not enter alone and Britain refused to go to war because it depended on food shipments from New York.[76]

Napoleon III attempted to gain British support when he invaded Mexico and forcibly put his pawn Maximilian I on the throne. London was unwilling to support any action other than the collection of debts owed by the Mexicans. This forced the French to act alone in the French Intervention in Mexico. Washington, after winning the civil war, threatened an invasion to expel the French and Napoleon pulled out its troops. Emperor Maximilian remained behind and was executed.[77] When Napoleon III was overthrown in 1870, he fled to exile in England.

Late 19th century

In the 1875–1898 era, tensions were high, especially over Egyptian and African issues. At several points, these issues brought the two nations to the brink of war; but the situation was always defused diplomatically.[78] For two decades, there was peace—but it was "an armed peace, characterized by alarms, distrust, rancour and irritation."[79] During the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s, the British and French generally recognised each other's spheres of influence. In an agreement in 1890 Great Britain was recognized in Bahr-el-Ghazal and Darfur, while Wadai, Bagirmi, Kanem, and the territory to the north and east of Lake Chad were assigned to France.[80]

The Suez Canal, initially built by the French, became a joint British-French project in 1875, as both saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia.[81] In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt (see Urabi Revolt) prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. France's expansionist Prime Minister Jules Ferry was out of office, and the government was unwilling to send more than an intimidating fleet to the region. Britain established a protectorate, as France had a year earlier in Tunisia, and popular opinion in France later put this action down to duplicity.[82] It was about this time that the two nations established co-ownership of Vanuatu. The Anglo-French Convention of 1882 was also signed to resolve territory disagreements in western Africa.

One brief but dangerous dispute occurred during the Fashoda Incident in 1898 when French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a British force purporting to be acting in the interests of the Khedive of Egypt arrived.[83] Under heavy pressure the French withdrew and Britain took control over the area, As France recognized British control of the Sudan. France received control of the small kingdom of Wadai, Which consolidated its holdings in northwest Africa. France had failed in its main goals. P.M.H. Bell says:

- Between the two governments there was a brief battle of wills, with the British insisting on immediate and unconditional French withdrawal from Fashoda. The French had to accept these terms, amounting to a public humiliation....Fashoda was long remembered in France as an example of British brutality and injustice."[84]

Fashoda was a diplomatic victory for the British because the French realized that in the long run they needed friendship with Britain in case of a war between France and Germany.[85][86][87]

The Entente Cordiale

From about 1900, Francophiles in Britain and Anglophiles in France began to spread a study and mutual respect and love of the culture of the country on the other side of the English Channel.[88] Francophile and Anglophile societies developed, further introducing Britain to French food and wine, and France to English sports like rugby. French and English were already the second languages of choice in Britain and France respectively. Eventually this developed into a political policy as the new united Germany was seen as a potential threat. Louis Blériot, for example, crossed the Channel in an aeroplane in 1909. Many saw this as symbolic of the connection between the two countries. This period in the first decade of the 20th century became known as the Entente Cordiale, and continued in spirit until the 1940s.[89] The signing of the Entente Cordiale also marked the end of almost a millennium of intermittent conflict between the two nations and their predecessor states, and the formalisation of the peaceful co-existence that had existed since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Up to 1940, relations between Britain and France were closer than those between Britain and the US.[90] This also started the beginning of the French and British Special Relationship. After 1907 the British fleet was built up to stay far ahead of Germany. However Britain nor France committed itself to entering a war if Germany attacked the other.[91]

In 1904 Paris and London agreed that Britain would establish a protectorate over Egypt, and France would do the same over Morocco. Germany objected, and the conference at Algeciras in 1906 settled the issue as Germany was outmaneuvered.[92]

First World War

Britain tried to stay neutral as the First World War opened in summer 1914, as France joined in to help its ally Russia according to its treaty obligations.[93] Britain had no relevant treaty obligations except one to keep Belgium neutral, and was not in close touch with the French leaders. Britain entered when the German army invaded neutral Belgium (on its way to attack Paris); that was intolerable. It joined France, sending a large army to fight on the Western Front.[94]

There was close co-operation between the British and French forces. French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre worked to coordinate Allied military operations and to mount a combined Anglo-French offensive on the Western Front. The result was the great Battle of the Somme in 1916 with massive casualties on both sides and no gains.[95] Paul Painlevé took important decisions during 1917 as France's war minister and then, for nine week's, premier. He promoted the Nivelle Offensive—which failed badly and had negative effects and its effects on the British Army. The positive result was the decision to form the Supreme War Council that led eventually to unity of command. The disasters at Passchendaele hurt Britain, its army and civil-military relations.[96]

Unable to advance against the combined primary alliance powers of the British, French, and later American forces as well as the blockade preventing shipping reaching German controlled North Sea seaports, the Germans eventually surrendered after four years of heavy fighting.[97]

Treaty of Versailles

Following the war, at the Treaty of Versailles the British and French worked closely with the Americans to dominate the main decisions. Both were also keen to protect and expand their empires, in the face of calls for self-determination. On a visit to London, French leader Georges Clemenceau was hailed by the British crowds. Lloyd George was given a similar reception in Paris.[98]

Lloyd George worked hard to moderate French demands for revenge. Clemenceau wanted terms to cripple Germany's war potential that were too harsh for Wilson and Lloyd George. A compromise was reached whereby Clemenceau softened his terms and the U.S. and Britain promised a Security Treaty that would guarantee armed intervention by both if Germany invaded France. The British ratified the treaty on condition the U.S. ratified. in the United States Senate, the Republicans were supportive, but Wilson insisted this security treaty be closely tied to the overall Versailles Treaty, and Republicans refused and so it never came to a vote in the Senate. Thus there was no treaty at all to help defend France.[99][100]

Britain soon had to moderate French policy toward Germany, as in the Locarno Treaties.[101][102] Under Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald in 1923–24 Britain took the lead in getting France to accept the American solution through the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan, whereby Germany paid its reparations using money borrowed from New York banks.[103][104]

1920s

Both states joined the League of Nations, and both signed agreements of defence of several countries, most significantly Poland. The Treaty of Sèvres split the Middle East between the two states, in the form of mandates. However the outlook of the nations were different during the inter-war years; while France saw itself inherently as a European power, Britain enjoyed close relationships with Australia, Canada and New Zealand and supported the idea of imperial free trade, a form of protectionism that would have seen large tariffs placed on goods from France.

In the 1920s, financial instability was a major problem for France, and other nations as well. it was vulnerable to short-term concerted action by banks and financial institutions by heavy selling or buying, in the financial crisis could weaken governments, and be used as a diplomatic threat. Premier and Finance Minister Raymond Poincaré decided to stabilise the franc to protect against political currency manipulation by Germany and Britain. His solution in 1926 was a return to a fixed parity against gold. France was not able to turn the tables and use short-term financial advantage as leverage against Britain on important policy matters.[105]

in general, France and Britain were aligned in their position on major issues. A key reason was the Francophile position of Foreign Minister Austen Chamberlain, and the ambassador to Paris the Marquess of Crewe (1922–28). They promoted a pro-French policy regarding French security and disarmament policy, the later stages of the Ruhr crisis, the implementation of the Geneva Protocol, the Treaty of Locarno and the origins of the Kellogg-Briand Pact.[106] The high point of cooperation came with the Treaty of Locarno in 1925, which brought Germany into good terms with France and Britain. However, relations with France became increasingly tense because Chamberlain grew annoyed that foreign minister Aristide Briand's diplomatic agenda did not have at its heart a reinvigorated Entente Cordiale.[107]

Furthermore, Britain thought disarmament was the key to peace but France disagreed because of its profound fear of German militarism. London decided Paris really sought military dominance of Europe. Before 1933, most Britons saw France, not Germany, as the chief threat to peace and harmony in Europe. France did not suffer as severe an economic recession, and was the strongest military power, but still it refused British overtures for disarmament.[108] Anthony Powell, in his A Dance to the Music of Time, said that to be anti-French and pro-German in the 1920s was considered the height of progressive sophistication.[109]

Appeasement of Germany

In the 1930s Britain and France coordinated their policies toward the dictatorships of Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany. However public opinion did not support going to war again, so the diplomats sought diplomatic solutions, but none worked. Efforts to use the League of Nations to apply sanctions against Italy for its invasion of Ethiopia failed. France supported the "Little Entente" of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. It proved much too weak to deter Germany.[110]

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement was signed between Britain and Nazi Germany in 1935, allowing Hitler to reinforce his navy. It was regarded by the French as the ruining of the anti-Hitlerian Stresa front. Britain and France collaborated closely especially in the late 1930s regarding Germany, based on informal promises with no written treaty. Efforts were made to negotiate a treaty but they failed in 1936, underscoring French weakness.[111]

In the years leading up to World War II, both countries followed a similar diplomatic path of appeasement of Germany. As Nazi intentions became clear, France pushed for a harder line but the British demurred, believing diplomacy could solve the disputes. The result was the Munich Agreement of 1938 that gave Germany control of parts of Czechoslovakia settled by Germans. In early 1939 Germany took over all of Czechoslovakia and began threatening Poland. Appeasement had failed, and both Britain and France raced to catch up with Germany in weaponry.[112]

Second World War

After guaranteeing the independence of Poland, both declared war on Germany on the same day, 3 September 1939, after the Germans ignored an ultimatum to withdraw from the country. When Germany began its attack on France in 1940, British troops and French troops again fought side by side. Eventually, after the Germans came through the Ardennes, it became more possible that France would not be able to fend off the German attack. The final bond between the two nations was so strong that members of the British cabinet had proposed a temporary union of the two countries for the sake of morale: the plan was drawn up by Jean Monnet, who later created the Common Market. The idea was not popular with a majority on either side, and the French government felt that, in the circumstances, the plan for union would reduce France to the level of a British Dominion. When London ordered the withdrawal of the British Expeditionary Force from France without telling French and Belgian forces[113] and then refused to provide France with further reinforcements of aircraft[114] the proposal was definitively turned down. Later The Free French resistance, led by Charles de Gaulle, were formed in London, after de Gaulle gave his famous 'Appeal of 18 June', broadcast by the BBC. De Gaulle declared himself to be the head of the one and only true government of France, and gathered the Free French Forces around him.[115][116]

War against Vichy France

After the preemptive destruction of a large part of the French fleet by the British at Mers-el-Kebir (3 July 1940), as well as a similar attack on French ships in Oran on the grounds that they might fall into German hands, there was nationwide anti-British indignation and a long-lasting feeling of betrayal in France.[117] In southern France a collaborative government known as Vichy France was set up on 10 July. It was officially neutral, but metropolitan France came increasingly under German control. The Vichy government controlled Syria, Madagascar, and French North Africa and French troops and naval forces therein. Eventually, several important French ships joined the Free French Forces.[117]

One by one de Gaulle took control of the French colonies, beginning with central Africa in autumn`1940, and gained recognition from Britain but not the United States. An Anglo-Free French attack on Vichy territory was repulsed at the Battle of Dakar in September 1940. Washington maintained diplomatic relations with Vichy (until October 1942) and avoided recognition of de Gaulle.[115][116] Churchill, caught between the U.S. and de Gaulle, tried to find a compromise.[115][116]

From 1941 British Empire and Commonwealth forces invaded Vichy controlled territory in Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Middle East. The first began in 1941 during the campaign against Syria and the Lebanon assisted with Free French troops. In two months of bitter fighting the region was seized and then put under Free French control. Around the same time after the Italian defeat in East Africa, Vichy controlled French Somaliland subsequently became blockaded by British and Free French forces. In a bloodless invasion the colony fell in mid 1942. In May 1942 the Vichy controlled island of Madagascar was invaded. In a seven-month campaign the island was seized by British Empire forces. Finally in the latter half of 1942 the British with the help of US forces took part in the successful invasion of French North Africa in Operation Torch. Most Vichy forces switched sides afterwards to help the allied cause during the Tunisian Campaign fighting as part of the British First Army.

Levant Crisis

Following D-Day, relations between the two peoples were at a high, as the British were greeted as liberators and remained so till the surrender of Germany in May 1945. At the end of that month, however, French troops, with their continued occupation of Syria, had tried to quell nationalist protests there. With heavy Syrian civilian casualties reported, Churchill demanded a ceasefire. With none forthcoming, he ordered British forces into Syria from Jordan. When they reached Damascus in June, the French were then escorted and confined to their barracks at gunpoint.[118] That became known as the Levant Crisis and almost brought Britain and France to the point of conflict. De Gaulle raged against 'Churchill's ultimatum' and reluctantly arranged a ceasefire. Syria gained independence the following year and France labelled British measures as a 'stab in the back'.[119]

1945–1956

The UK and France nevertheless became close as both feared the Americans would withdraw from Europe leaving them vulnerable to the Soviet Union's expanding communist bloc. The UK was successful in strongly advocating that France be given a zone of occupied Germany. Both states were amongst the five Permanent Members of the new UN Security Council, where they commonly collaborated. However, France was bitter when the United States and Britain refused to share atomic secrets with it. An American operation to use air strikes (including the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons) during the climax of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954 was cancelled because of opposition by the British.[120][121] The upshot was France developed its own nuclear weapons and delivery systems.[122]

The Cold War began in 1947, as the United States, with strong British support, announced the Truman Doctrine to contain Communist expansion and provided military and economic aid to Greece and Turkey. Despite its large pro-Soviet Communist Party, France joined the Allies. The first move was the Franco-British alliance realized in the Dunkirk Treaty in March 1947.[123]

Suez Crisis

In 1956 the Suez Canal, previously owned by an Anglo-French company, was nationalised by the Egyptian government. The British and the French were both strongly committed to taking the canal back by force.[124] President Eisenhower and the Soviet Union demanded there be no invasion and both imposed heavy pressure to reverse the invasion when it came. The relations between Britain and France were not entirely harmonious, as the French did not inform the British about the involvement of Israel until very close to the commencement of military operations.[125] The failure in Suez convinced Paris it needed its own nuclear weapons.[126][127]

Common Market

Immediately after the Suez crisis Anglo-French relations started to sour again, and only since the last decades of the 20th century have they improved towards the peak they achieved between 1900 and 1940.

Shortly after 1956, France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg formed what would become the European Economic Community and later the European Union, but rejected British requests for membership. In particular, President Charles de Gaulle's attempts to exclude the British from European affairs during France's early Fifth Republic are now seen by many in Britain as a betrayal of the strong bond between the countries, and Anthony Eden's exclusion of France from the Commonwealth is seen in a similar light in France. The French partly feared that were the British to join the EEC they would attempt to dominate it.

Over the years, the UK and France have often taken diverging courses within the European Community. British policy has favoured an expansion of the Community and free trade while France has advocated a closer political union and restricting membership of the Community to a core of Western European states.

De Gaulle

In 1958 with France mired in a seemingly unwinnable war in Algeria, de Gaulle returned to power in France. He created the Fifth French Republic, ending the post-war parliamentary system and replacing it with a strong Presidency, which became dominated by his followers—the Gaullists. De Gaulle made ambitious changes to French foreign policy—first ending the war in Algeria, and then withdrawing France from the NATO command structure. The latter move was primarily symbolic, but NATO headquarters moved to Brussels and French generals had a much lesser role.[128][129]

French policy blocking British entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) was primarily motivated by political rather than economic considerations. In 1967, as in 1961–63, de Gaulle was determined to preserve France's dominance within the EEC, which was the foundation of the nation's international stature. His policy was to preserve the Community of Six while barring Britain. Although France succeeded in excluding Britain in the short term, in the longer term the French had to adjust their stance on enlargement in order to retain influence. De Gaulle feared that letting Britain into the European Community would open the way for Anglo-Saxon (i.e., US and UK) influence to overwhelm the France-West Germany coalition that was now dominant. On 14 January 1963, de Gaulle announced that France would veto Britain's entry into the Common Market.[130]

Since 1969

When de Gaulle resigned in 1969, a new French government under Georges Pompidou was prepared to open a more friendly dialogue with Britain. He felt that in the economic crises of the 1970s Europe needed Britain. Pompidou welcomed British membership of the EEC, opening the way for the United Kingdom to join it in 1973.[132]

The two countries' relationship was strained significantly in the lead-up to the 2003 War in Iraq. Britain and its American ally strongly advocated the use of force to remove Saddam Hussein, while France (with China, Russia, and other nations) strongly opposed such action, with French President Jacques Chirac threatening to veto any resolution proposed to the UN Security Council. However, despite such differences Chirac and then British Prime Minister Tony Blair maintained a fairly close relationship during their years in office even after the Iraq War started.[133] Both states asserted the importance of the Entente Cordiale alliance, and the role it had played during the 20th century.

Sarkozy presidency

Following his election in 2007, President Nicolas Sarkozy attempted to forge closer relations between France and the United Kingdom: in March 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown said that "there has never been greater cooperation between France and Britain as there is now".[134] Sarkozy also urged both countries to "overcome our long-standing rivalries and build together a future that will be stronger because we will be together".[135] He also said "If we want to change Europe my dear British friends—and we Frenchmen do wish to change Europe—we need you inside Europe to help us do so, not standing on the outside."[136] On 26 March 2008, Sarkozy had the privilege of giving a speech to both British Houses of Parliament, where he called for a "brotherhood" between the two countries[137] and stated that "France will never forget Britain's war sacrifice" during World War II.[138]

In March 2008, Sarkozy made a state visit to Britain, promising closer cooperation between the two countries' governments in the future.[139]

Hollande presidency

The final months towards the end of François Hollande's tenure as president saw the UK vote to leave the EU. His response to the result was "I profoundly regret this decision for the United Kingdom and for Europe, but the choice is theirs and we have to respect it."[140]

The then-Economy Minister and current President Emmanuel Macron accused the UK of taking the EU "hostage" with a referendum called to solve a domestic political problem of eurosceptics and that "the failure of the British government [has opened up] the possibility of the crumbling of Europe."[141]

In contrast, the vote was welcomed by Eurosceptic political leaders and presidential candidates Marine Le Pen and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan as a victory for "freedom".[142][143]

Defence Cooperation

The two nations have a post WWII record of working together on international security measures, as was seen in the Suez Crisis and Falklands War. In her 2020 book, Johns Hopkins University SAIS political scientist Alice Pannier writes that there is a growing "special relationship" between France and the UK in terms of defence cooperation.[144]

On 2 November 2010, France and the UK signed two defence co-operation treaties. They provide for the sharing of aircraft carriers, a 1000-strong joint reaction force, a common nuclear simulation centre in France, a common nuclear research centre in the UK, sharing air-refuelling tankers and joint training.[145][146]

Their post-colonial entanglements have given them a more outward focus than the other countries of Europe, leading them to work together on issues such as the Libyan Civil War.[147]

Commerce

France is the United Kingdom's third-biggest export market after the United States and Germany. Exports to France rose 14.3% from £16.542 billion in 2010 to £18.905 billion in 2011, overtaking exports to the Netherlands. Over the same period, French exports to Britain rose 5.5% from £18.133 billion to £19.138 billion.[148]

The British Foreign & Commonwealth Office estimates that 19.3 million British citizens, roughly a third of the entire population, visit France each year.[149] In 2012, the French were the biggest visitors to the UK (12%, 3,787,000) and the second-biggest tourist spenders in Britain (8%, £1.513 billion).[150]

Education

The Entente Cordiale Scholarship scheme is a selective Franco-British scholarship scheme which was announced on 30 October 1995 by British Prime Minister John Major and French President Jacques Chirac at an Anglo-French summit in London.[151]

It provides funding for British and French students to study for one academic year on the other side of the Channel. The scheme is administered by the French embassy in London for British students,[152] and by the British Council in France and the UK embassy in Paris for French students.[153][154] Funding is provided by the private sector and foundations. The scheme aims to favour mutual understanding and to promote exchanges between the British and French leaders of tomorrow.

The programme was initiated by Sir Christopher Mallaby, British ambassador to France between 1993 and 1996.[155]

The sciences

The Concorde supersonic commercial aircraft was developed under an international treaty between the UK and France in 1962, and commenced flying in 1969.[156]

Arts and culture

In general, France is regarded with favour by Britain in regard to its high culture and is seen as an ideal holiday destination, whilst France sees Britain as a major trading partner. Both countries are famously contemptuous of each other's cooking, many French claiming all British food is bland and boring, whilst many British claim that French food is inedible. Much of the apparent disdain for French food and culture in Britain takes the form of self-effacing humour, and British comedy often uses French culture as the butt of its jokes. Whether this is representative of true opinion or not is open to debate. Sexual euphemisms with no link to France, such as French kissing, or French letter for a condom, are used in British English slang.[157] While in French slang, the term le vice anglais refers to either BDSM or homosexuality.[158]

French classical music has always been popular in Britain. British popular music is in turn popular in France. English literature, in particular the works of Agatha Christie and William Shakespeare, has been immensely popular in France. French artist Eugène Delacroix based many of his paintings on scenes from Shakespeare's plays. In turn, French writers such as Molière, Voltaire and Victor Hugo have been translated numerous times into English. In general, most of the more popular books in either language are translated into the other.

Language

The first foreign language most commonly taught in schools in Britain is French, and the first foreign language most commonly taught in schools in France is English; those are also the languages perceived as "most useful to learn" in both countries. Queen Elizabeth II of the UK is fluent in French and does not require an interpreter when travelling to French-language countries.[159][160] French is a substantial minority language and immigrant language in the United Kingdom, with over 100,000 French-born people in the UK. According to a 2006 European Commission report, 23% of UK residents are able to carry on a conversation in French and 39% of French residents are able to carry on a conversation in English.[161] French is also an official language in both Jersey and Guernsey. Both use French to some degree, mostly in an administrative or ceremonial capacity. Jersey Legal French is the standardized variety used in Jersey. However, Norman (in its local forms, Guernésiais and Jèrriais) is the historical vernacular of the islands.

Both languages have influenced each other throughout the years. According to different sources, nearly 30% of all English words have a French origin, and today many French expressions have entered the English language as well.[162] The term Franglais, a portmanteau combining the French words "français" and "anglais", refers to the combination of French and English (mostly in the UK) or the use of English words and nouns of Anglo-Saxon roots in French (in France).

Modern and Middle English reflect a mixture of Oïl and Old English lexicons after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, when a Norman-speaking aristocracy took control of a population whose mother tongue was Germanic in origin. Due to the intertwined histories of England and continental possessions of the English Crown, many formal and legal words in Modern English have French roots. For example, buy and sell are of Germanic origin, while purchase and vend are from Old French.

Sports

In the sport of rugby union there is a rivalry between England and France. Both countries compete in the Six Nations Championship and the Rugby World Cup. England have the edge in both tournaments, having the most outright wins in the Six Nations (and its previous version the Five Nations), and most recently knocking the French team out of the 2003 and 2007 World Cups at the semi-final stage, although France knocked England out of the 2011 Rugby World Cup with a convincing score in their quarter final match. Though rugby is originally a British sport, French rugby has developed to such an extent that the English and French teams are now stiff competitors, with neither side greatly superior to the other. While English influences spread rugby union at an early stage to Scotland, Wales and Ireland, as well as the Commonwealth realms, French influence spread the sport outside the commonwealth, to Italy, Argentina, Romania and Georgia.

The influence of French players and coaches on British football has been increasing in recent years and is often cited as an example of Anglo-French cooperation. In particular the Premier League club Arsenal has become known for its Anglo-French connection due to a heavy influx of French players since the advent of French manager Arsène Wenger in 1996. In March 2008 their Emirates stadium was chosen as the venue for a meeting during a state visit by the French President precisely for this reason.[163]

Many people blamed the then French President Jacques Chirac for contributing to Paris' loss to London in its bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics after he made derogatory remarks about British cuisine and saying that "only Finnish food is worse". The IOC committee which would ultimately decide to give the games to London had two members from Finland.[164]

Transport

Ferries