Fort Crevecoeur

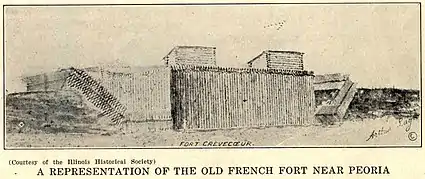

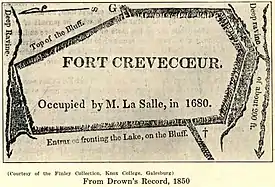

Fort Crevecoeur (French: Fort Crèvecœur) was the first public building erected by Europeans within the boundaries of the modern state of Illinois and the first fort built in the West by the French.[1] It was founded on the east bank of the Illinois River, in the Illinois Country near the present site of Creve Coeur, a suburb of Peoria, Illinois, in January 1680. It was destroyed on 16 April of that same year by members of La Salle's expedition, who were fearful of being attacked by the Iroquois as the Beaver Wars extended into the area.[2]

| Fort Crevecoeur | |

|---|---|

| Native name Fr: Fort Crèvecœur | |

| |

| Location | present-day Creve Coeur, Illinois |

| Built | 1680 |

| Rebuilt | Destroyed in 1680 and replaced by Fort Pimiteoui in 1691 |

Reestablishing a more lasting presence, Fort St Louis du Pimiteoui was established nearby in 1691, a center of trade during the colonial period. Henri de Tonti was a primary founder of both the Crevecouer and Pimiteoui posts.

Founding

On January 15, 1680, French explorers René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti began construction of Fort Crèvecoeur.[2] in which Mass was celebrated and the Gospel preached by the Récollets, Gabriel Ribourde, Zenobius Membre and Louis Hennepin.[3] They finished the fort in early March, naming it "Fort Broken Heart" because of the tribulations, including desertions, that they suffered during its construction. Dr. Daniel Coxe wrote in 1719:

Monsieur LaSalle erected a fort in the year 1680, which he named Crève-coeur, from the Grief which seiz'd him on the Loss of one of his chief trading Barks richly laden, and the Mutiny and villianous Intrigues of some of his Company, who first attempted to poyson and afterwards desert him.[4]

La Salle also started building a 40-ton barque to replace Le Griffon, which had disappeared several months before.[5] On March 1, 1680, La Salle set off on foot for Fort Frontenac for supplies (including rigging for the ship),[1] leaving Henri de Tonti to hold Fort Crèvecoeur in Illinois.[6]

Destruction

While on his return trip up the Illinois River, La Salle concluded that Starved Rock might provide an ideal location for another fortification and sent word downriver to Tonti regarding this idea. Following La Salle’s instructions, Henri de Tonti had left Fort Crèvecoeur on April 15, 1680 with Father Ribourde and two other men, to begin fortifying the settlement and Fort St. Louis at Starved Rock.[2] The next day, the remaining seven men, led by Martin Chartier,[7] pillaged Fort Crèvecoeur of all provisions and ammunition, destroyed the fort and headed back to Canada.[2]

The mutiny was probably caused by the men's fear of being killed by Iroquois raiding parties, who were devastating the local Illinois communities at the height of the Beaver Wars. The men were demanding that La Salle return with them to Canada, which he was unwilling to do.[5] In addition, one of the mutineers who was later captured, the shipbuilder Moyse Hillaret, testified that "some [of the men] had had no pay for three years," and alleged that La Salle had mistreated them.[8][9]

In a deposition made before the Sieur du Chesneau, Intendant of New France, dated 17 August 1680, Hillaret stated the mutineers were dissatisfied "because the said Sieur de La Salle wanted them to build sleighs to draw his goods and personal effects as far as the village of the Illinois [the site of the proposed Fort St. Louis (Starved Rock)]."[9]

Joining Tonti at Starved Rock, two men who had been at the fort told him of the fort's destruction. Tonti sent messengers to La Salle in Canada to report the events. Tonti then returned to Fort Crèvecoeur to collect any tools not destroyed[2] and moved them to the Kaskaskia Village near Starved Rock. The mutineers, assisted by some other men they recruited along the way, looted some of La Salle's possessions at Michilimackinac and at Fort Niagara, then split into two groups, one of which went to Albany and the second to Fort Frontenac, reportedly with the intention of finding and killing La Salle.[2] In August, La Salle recaptured some of the mutineers, however Chartier took refuge with a band of Shawnee Indians and went with them to Pennsylvania.[7]

On September 10, 1680, nearly six hundred Iroquois warriors, armed with guns, approached the Kaskaskia village.[2] Meeting them in advance, de Tonti was accused of treachery, by both the Iroquois and the Illinois Confederation.[2] Tonti tried to mediate their disagreements and delay the Iroquois attack until the women, children and old people could escape from the village. Tonti was wounded by an Iroquois man, who stabbed him with a knife.[2] The Kaskaskia village was burned and the Iroquois built a fort on that site near Starved Rock. Tonti with his allies fled the area, heading for La Baye.[2]

Fort St. Louis du Pimiteoui

In 1691, Tonti returned to the area and founded another fort. This fort is known variously as Fort St. Louis du Pimiteoui, Fort Pimiteoui, and Old Fort Peoria (Pimiteoui – English: Fat Lake – was the name of what is now called, Peoria Lake, a stretch where the Illinois River significantly widens). It remained off and on a center of trade, particularly fur trade, and sometimes settlement throughout the colonial period.[10]

References

- "The Site of Fort de Crèvecoeur", University of Illinois, 1925.

- "History of Fort Crevecoeur". Fort Crevecoeur Park website. Fort Crevecoeur Inc. 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Jean-Roch Rioux, "Louis Hennepin," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003

- Daniel Coxe, "A Description of the Great and Famous River Meschacebe or Missisippi, the Rivers increasing it both from the East and West, the Countries adjacent, and the Several Nations of Indians inhabiting therein," in A description of the English province of Carolana, by the Spaniards call'd Florida, and by the French La Louisiane, 1722 ed. published by B. Cowse, London.

- Francis Parkman, "La Salle And The Discovery Of The Great West," American Heritage, April 1957, Volume 8, Issue 3.

- "La Salle," New International Encyclopedia, Volume 13, Second Edition, Dodd, Mead, 1915; p. 581.

- Charles Augustus Hanna, The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Volume 1, Putnam's sons, 1911

- Harriette Simpson Arnow, Seedtime on the Cumberland, Michigan State University Press. (2013)

- "Déclaration faite par devant le Sr. Duchesneau, Intendant en Canada, par Moyse Hillaret, charpentier de barque cy-devant au service du Sr. de la Salle, Aoust, 1680." cited in Francis Parkman, La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West: France and England in North America. Part Third, vol. V-VI; Little, Brown, 1897.

- "Illinois; a Descriptive and Historical Guide, - Best Books on, Federal Writers' Project - Google Books". Federal Writers Project on Books.google.com. p. 359. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

Further reading

- Ross, Ryan A. "The Controversy over the Location of Fort Crèvecoeur, 1846-1923," Journal of Illinois History 14:4 (Winter 2011), pp. 277–92.