Fire of Manisa

The Fire of Manisa (Turkish: Manisa yangını) refers to the burning of the town of Manisa, Turkey which started on the night of Tuesday 5 September 1922 and continued until 8 September.[1] It was started and organized by the retreating Greek troops[2][4][6] during the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), and as a result 90 percent of the buildings in the town were destroyed.[7][8] The number of victims in the town and adjacent region was estimated to be several thousand by US Consul James Loder Park.[4] Turkish sources claim that 4355 people died in the town of Manisa.[3][5]

| Part of Greek scorched-earth policy during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) | |

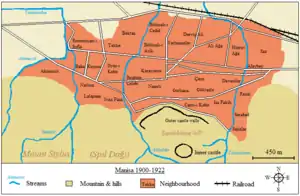

Map of the town and its neighborhoods before the fire. | |

| Date | 5–8 September 1922[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | Manisa, Turkey |

| Participants | Greek army[2] According to Turkish sources, local Greek and Armenian irregulars played a significant role.[3] |

| Outcome | Ninety percent (~10,000 buildings) destroyed,[4] town later rebuild. |

| Deaths | Exact number unknown, according to US consul James Loder Park thousands of atrocities [note 1] according to Turkish sources 4.355 died[note 2] |

Background

Manisa is a historic town in Western Anatolia beneath the north side of Mount Sipylus that became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. During Ottoman rule the town was governed by several princes[7] (called Şehzade) and so is also known as a "town of the princes" (Şehzadeler şehri). Many examples of Ottoman architecture were built over the next few centuries, such as the Muradiye Mosque, designed by the famous architect Mimar Sinan in 1586,[9] and built for Murad III who was a governor of the town.[10]

By the 19th century Manisa was among the largest towns in the Aegean region of Anatolia and its population before the fire is estimated to have been between 35,000[11] and 50,000.[12] Manisa had a religiously and ethnically diverse population made up of Muslims, Christians and Jews but Turkish Muslims were the largest group. During the 19th century there was an increase in other groups, most notably Greeks. In 1865 the population was estimated by the British at 40,000 with minorities of 5,000 Greeks, 2,000 Armenians and 2,000 Jews.[13] In 1898 the population was estimated by the Ottoman linguist Sami Bey at 36,252 of which 21,000 were Muslims, 10,400 Greeks, and 2,000 Armenians.[14]

After World War I, Greece, supported by the Allied Powers, decided that the area known as the "Smyrna territory" would be occupied and could later be incorporated into Greece. In accordance with this plan, Greek forces (with Allied support) landed in Smyrna on 15 May 1919 and the town was occupied on 26 May without armed opposition.[note 3] [15] During the occupation which lasted more than three years, there were complaints by the local Turks of bad treatment.[3][note 4] During the Greco-Turkish War that followed the Greek invasion, atrocities were committed by both Turks and Greeks.

Fire

A Turkish offensive started in August 1922 and the Greek army retreated towards Smyrna and the Aegean coast. During their retreat they practiced a scorched earth policy, burning towns and villages and committing atrocities along the way.[16][6][4][17] Towns to the east of Manisa, such as Alaşehir and Salihli were burned.[4] Several days before the actual fire in Manisa, rumors were going around that the town would be burned.[3] Turkish sources claim that the Greek and Armenian population got permission to leave from the Greek army and had already evacuated the area.[3] Other sources confirm that the Christians fled before the Turkish advance.[16] The Turkish sources claim that the local Turks and Muslims were ordered to stay in their houses[3] which most did until the day on which the fire started.

The burning of the town was carefully managed by the Greek army,[4] and fires were started at multiple places by specially organized groups.[note 5] According to Turkish sources a significant number of the arsonists were local Greeks and Armenians[note 6].[3] During the night of Tuesday 5 September and the morning of 6 September, fires were started in the commercial Çarşı district (while looted was taking place) and at various other sites.[3] Many people left their houses and fled to safety in the mountains and hills.[1][18] During this chaos some people were killed by the Greeks or burnt to death.[3][4] The population hid in the mountains for several days.[3][18] Meanwhile, the Turkish army continued its rapid advance and, after some fighting with remaining Greek troops, they took control of the remains of the town on 8 September.[1] By then most of the town had been destroyed.

Gülfem Kaatçılar İrem, witnessed the fire as a little girl and remembers when she fled to the hills with her family:

After escaping the militia towards dawn, we climbed up a dry stream bed to hide in the hills. As we climbed, the city was burning, and we were lit by its light and warmed by its heat. It burned for three days and three nights. I saw the windowpanes of houses explode like bombs. Sacks of grapes stuck together, bubbling like jam. Dead cows and horses, balloons with their legs in the air. Ancient trees keeled over, their roots burning like logs. I did not forget these things. The heat, the hunger, the fear, the smell. After three days we saw the dust rise in the valley below. Turkish soldiers on horseback; we thought they were Greeks come to kill us in the hills. I remember three soldiers carrying green and red flags. People kissed the hooves of their horses, crying "Our saviors have come."[18]

Aftermath

The town was almost entirely rebuilt according to a modern plan by a Turkish architect named Cemalettin.[19] The town is believed to have lost many buildings and objects of historical significance, but a small area around the two imperial Ottoman mosques were saved from destruction. Today the town has grown again and had reached 309,050 inhabitants in 2012.[20]

Damage

The Turkish government set up a commission called Tetkik-i Mezalim or Tetkik-i Fecayi Heyeti "the atrocity committee" to research and document the events and atrocities.[3] Turkish author Halide Edip saw the town after the fire, as did Henry Franklin-Bouillon, the French government representative, who declared that out of 11,000 houses in the city of Magnesia (Manisa) only 1,000 remained.[21] Patrick Kinross wrote, "Out of the eighteen thousand buildings in the historic holy city of Manisa, only five hundred remained."[6] The total economic damage was estimated to be more than fifty million lira (in contemporary value).[3] Some of the captured Greek soldiers were employed in the reconstruction, such as in the rebuilding of the destroyed Karaköy mosque.[3]

Loder Park, who toured much of the devastated area immediately after the Greek evacuation, described the situation he had seen as follows:[4]

Manisa ... almost completely wiped out by fire ... 10,300 houses, 15 mosques, 2 baths, 2,278 shops, 19 hotels, 26 villas ... [destroyed]..."

"1. The destruction of the interior cities visited by our party was carried out by Greeks.""3. The burning of these cities was not desultory, nor intermittent, nor accidental, but well planned and thoroughly organized."

"4. There were many instances of physical violence, most of which was deliberate and wanton. Without complete figures, which were impossible to obtain, it may safely be surmised that 'atrocities' committed by retiring Greeks numbered well into thousands in the four cities under consideration. These consisted of all three of the usual type of such atrocities, namely murder, torture and rape."

Victims

The total number of victims during the fire is not known. Turkish sources estimate that 3,500 died in the fires and 855 were shot.[3][5] A comparison can be made with several nearby towns which were also burned by the retreating Greeks. There were estimated to be 3,000[22] victims in Alaşehir and 1,000 in Turgutlu.[4] The number that were wounded is also unknown. Turkish sources state that three hundred girls were raped and abducted by the Greeks.[3] Many rape victims were thought to have remained silent out of fear or shame.[3] A number of Greeks troops were captured, some of them were lynched by the Turkish women they had raped.[3]

The Greek retreat was accompanied by looting and other people lost their possessions in the fires,[23] and lived for some time among the ruins of their homes or crowded together in the surviving buildings.[24]

In Turkish literature

The event is mentioned in a work by Turkish journalist Falih Rıfkı Atay.[25] The Turkish poet İlhan Berk was a small child living in the Deveciler neighborhood at the time of the fire and fled to the mountains with his family. His older sister burned to death in their house. He wrote that he could never forget the flight to the mountains and wrote of other childhood memories of the events in his work Uzun Bir Adam.[24] The historian Kamil Su, also witnessed the fire as a 13-year-old living in the Alaybey neighborhood.[3] On the morning of September 6 he fled with his family to the mountains. When he returned to his neighborhood he found corpses in the streets and most buildings razed to their foundations, only the walls of the historic Aydın mosque were still standing;[3] the corpse of an unknown man lay in the street in front of where Su's house had stood.[3] He later wrote Manisa ve Yöresinde İşgal Acıları, a book about the Greek occupation and the fire.[3]

Gallery

A view from the hills above the town.

A view from the hills above the town. Picture taken from the north in southerly direction, showing Mount Sipylus and in the distance the Ulu Camii, grand mosque, built in 1366.

Picture taken from the north in southerly direction, showing Mount Sipylus and in the distance the Ulu Camii, grand mosque, built in 1366. The reconstruction of the burned Municipal building.

The reconstruction of the burned Municipal building.

See also

- Fire of Smyrna (occurred a short time after Manisa on 13 September 1922)

Notes

- There were many instances of physical violence, most of which was deliberate and wanton. Without complete figures, which were impossible to obtain, it may safely be surmised that 'atrocities' committed by retiring Greeks numbered well into thousands in the four cities under consideration. These consisted of all three of the usual type of such atrocities, namely murder, torture and rape[4]

- 855 shot dead and 3.500 burned to death [3][5]

- Some local Turks collaborated with the Greeks authorities such as the sub-governor Giritli Hüsnü who fled with the Greeks before the fire.[3]

- The town could only be left with soldier's permission, occasional murders, rapes, theft, looting and desecration of Muslim mosques and Muslim graveyards by the Greeks. Some Turkish villages around the town had been burned (On 25 June 1919, Cin Obası village was burned and the men killed ) or looted (24–25 July 1919, Develi, Koldere, Mütevelli, Kumkuyucak, Çerkesyenice. In January 1920, Keçili).[3]

- Turkish sources claim that the fire was organised by lieutenant colonel Filipos and colonel Bagorçi.[3]

- especially Armenian refugees from Cilicia who were very hostile to the Turks.[3]

References

- Emecen, Feridun Mustafa (2006). Tarihin içinde Manisa. Manisa Belediyesi. p. 6. ISBN 9789759550608.

Yunan kuvvetleri çekilirken 5 Eylül Salı günü şehri ateşe verdiler, akşam söndürülen yangın sabah çarşı kesiminde tekrar başladı ve 8 Eylül'de kendiliğinden söndü. Yangın sırasında halk dağlara kaçtı, bu büyük yangın neredeyse şehrin tamamını etkiledi, 10.700 ev, on üç cami, 2728 dükkân, on dokuz han yandı, Manisa tam bir harabeye dönüştü. 8 Eylül'de Türk birlikleri Manisa yakınlarındaki küçük bir çarpışmanın ardından şehre girdi. Cumhuriyet döneminde bu tahribatın izleri kapandı ve şehir yeniden gelişmeye başladı. (English) "The Greek forces, while retreating, set the city on fire on 5 Tuesday, September it was extinguished in the evening but began again the following morning in the market sector and on 8 September was extinguished by itself. During the fire the people fled to the mountains, this great fire affected almost the entire city, 10,700 houses, thirteen mosques, 2,728 shops and nineteen inn were burned, Manisa became a complete ruin. On 8 September after a minor collision near Manisa, the Turkish troops entered the city. In the Republican period, the traces of this destruction disappeared, and the city began to flourish again. "

- Freely, John (2010). Children of Achilles: The Greeks in Asia Minor Since the Days of Troy. .B.Tauris. p. 212. ISBN 9781845119416.

Manisa, which was burned to the ground by the Greeks when they evacuated the town.

- Su, Kamil (1982). Manisa ve yöresinde işgal acıları. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı. pp. 26–87.

- U.S. Vice-Consul James Loder Park to Secretary of State, Smyrna, 11 April 1923. US archives US767.68116/34

- Ergül, Teoman (1991). Kurtuluş Savaşında Manisa, 1919-1922. Manisa Kültür Sanat Kurumu. p. 337.

Daha acısı 3500 kişi ateşte yakılmak ve 855 kişi kurşunlanmak suretiyle öldürülmüştü. Üç yüz kızın ırzına geçilmişti. Sadece bir mahalleden 500 kişi götürülmüştü. Ölü veya diri oldukları hakkında bir bilgi alınamamiştır. (English) "The more painful, that 3500 people were burned to death and 855 people were shot dead. Three hundred girls were raped. From only one district, 500 people were taken away. Their fate was unknown."

- Kinross 1960, p. 318.

- Ayliffe, Rosie (2003). Turkey. Rough Guides. p. 313. ISBN 9781843530718.

Later, the Ottomans sent heirs to the throne here (Manisa) to serve an apprenticeship as local governors, in order to ready them for the rigours of Istanbul palace life.

- U.S. Vice-Consul James Loder Park to Secretary of State, Smyrna, 11 April 1923. US archives US767.68116/34

Consul Park concluded:

"1. The destruction of the interior cities visited by our party was carried out by Greeks."

"2. The percentages of buildings destroyed in each of the last four cities referred to were: Manisa 90 percent, Cassaba (Turgutlu) 90 percent, Alaşehir 70 percent, Salihli 65 percent."

"3. The burning of these cities was not desultory, nor intermittent, nor accidental, but well planned and thoroughly organized."

"4. There were many instances of physical violence, most of which was deliberate and wanton. Without complete figures, which were impossible to obtain, it may safely be surmised that 'atrocities' committed by retiring Greeks numbered well into thousands in the four cities under consideration. These consisted of all three of the usual type of such atrocities, namely murder, torture and rape."

"Cassaba (present day Turgutlu) was a town of 40,000 souls, 3,000 of whom were non-Muslims. Of these 37,000 Turks only 6,000 could be accounted for among the living, while 1,000 Turks were known to have been shot or burned to death." - Richardson, Terry; Dubin, Marc (2013). The Rough Guide to Turkey. Rough Guides UK. ISBN 9781409332473.

- Jayyusi, Salma Khadra; Holod, Renata; Raymond, André; Attilio Petruccioli, Attilio Petruccioli (2008). The City in the Islamic World. BRILL. p. 469. ISBN 9789004171688.

Murat III (1574–1595) donated his Muradiye to the town of Manisa, one of the two Anatolian seats of crown princes.

- United States. Dept. of State (1866). Papers Relating to Foreign Affairs, 3. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 311.

this is a florishing city of about 35,000 inhabitants, about one-fourth of whom are Greeks and Armenians

- Adams, Charles Kendall (1895). Johnson's universal cyclopaedia, Volume 8. A.J. Johnson Co. p. 310.

- Clarke, Hyde (1865). On the Supposed Extinction of the Turks and Increase of the Christians in Turkey. A paper read before the Statistical Society of London. Journal of the Statistical Society of London. p. 283.

- M., Th. Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 5. BRILL. p. 246. ISBN 9789004097919.

- ÇAGRI, ERHAN (1999). "GREEK OCCUPATION OF IZMIR AND ADJOINING TERRITORIES REPORT OF THE INTER-ALLIED COMMISSION OF INQUIRY (MAY-SEPTEMBER 1919)" (PDF). SAM PAPERS No. 2/99. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Chenoweth, Erica (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-state Actors in Conflict. MIT Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780262014205.

The Turkish counter-offensive, which began in August 1922, routed the Greeks and within two weeks led to the evacuation of what remained of the Greek Army from Smyrna. The retreating Greeks left a trail of scorched earth behind them as they torched Turkish towns and villages along their line of retreat, killing thousands in the process. Christian civilians (Greeks and Armenians) fled before the advancing Turks.

- Fisher 1969, p. 386.

- Neyzi, Leyla (2008). Remembering Smyrna/Izmir (PDF). History and Memory. p. 115.

As Manisa was torched by the Greeks, the townspeople fled to the hills. It was here that they would remain "for three days and three nights."

- KARAKAYA, EMEL. RECONSTRUCTION OF ANATOLIA FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATION-STATE: ROLES ATTAINED TO ANKARA AND İZMİR (PDF). 15th INTERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY CONFERENCE.

- "Main cities". Geohive. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "Turks halt embarkation of all Smyrna refugees; Quit the neutral zone" (PDF). Rome Daily Sentinel. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

visiting the areas devastated by the Greeks. He declared that out of 11.000 houses in the city of Magnesia only 1.000 remained

- Mango 1999, p. 343.

- Hirschon, Renée (2008). Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey. Berghahn Books. p. 200. ISBN 9780857457028.

- ŞEN, Can (2013). "MANISA IN ILHAN BERK'S CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH MEMORIES" (PDF). Celal Bayar Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü. 3 (11): 348–349. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

lived his childhood and youth years in Manisa. In his work entitled "A Tall Man", the poet included his Manisa memories

- Atay, Falih Rıfkı (1984). Çankaya. İstanbul. p. 331.

Henüz çürümeyen cesetler ve neredeyse henüz tüten yangınlar içinden geçiyorduk. Yanıp külleri savrulan Manisa'ya, cetlerimizin şehrine iki eli böğründe bakakaldık. Yunanlılar çekilişlerinde yok edici bir tahrip yapmışlardı. Yanmayanlar, vakit bulup da yakamadıkları, yaşayanlar fırsat bulup da öldüremedikleri idi. İki millet arasında yalnız birinin arta kalacağı bir boğazlaşma geçmiş olduğunu görüyorduk. Yunanlılar Batı Anadolu'yu Türkler için oturulmaz bir çöle çevirmek istemişlerdi…

Bibliography

- Fisher, Sydney Nettleton (1969), The Middle East: a History, New York: Alfred A Knopf

- Kinross, Lord (1960). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-82036-9.